Archives of Thursday Comics Hangover

Thursday Comics Hangover: The Fantastic Four and the problem with adaptations

Usually, this column is about new comics I bought on Wednesday. But last night I went to a press screening for the Fantastic Four movie that opens tomorrow, and I want to talk about that for a bit instead. (If you're looking for a straight-up movie review, you can read my review at Prairie Dog.)

The first 102 issues of the Fantastic Four by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee are basically the template for every adventure comic book that came after: big sci-fi ideas, big discoveries, comic relief, and personal drama. Not every issue is a classic — Tomazooma the Living Totem wasn't the huge character find of 1968 — but the whole run is quite impressive.

So since there's already a blueprint out there clearly explaining what the Fantastic Four should be, why is it so incredibly hard to make a Fantastic Four movie? Why has every Fantastic Four adaptation been a bust? (Some people like to insist that The Incredibles is a good Fantastic Four movie, but that's not quite right. The Incredibles gets the family dynamic right, but they're superheroes. The Fantastic Four are sci-fi adventurers. It's an important distinction to make, because it's an entirely different motivation.)

What we're talking about here is a problem of adaptation. Everyone knows adaptation is tough; you can't just take a comic and duplicate it onto a movie screen (though Zack Snyder certainly tried during the making of Watchmen.) It's almost a cliche at this point to suggest that what doesn't go into an adaptation is just as important as what does. But it's true.

The new Fantastic Four movie is outright terrible; it replaces the optimistic post-Kennedy vibe of the comics with a dour fear of being different. So why can filmmakers create wonderful, fairly faithful adaptations of Captain America and Batman, but nobody is able to toss the Fantastic Four up on a screen? It's not because of the corny name.

Maybe the answer has to do with the fact that the Fantastic Four is a family, and modern blockbusters don't have the patience to depict families beyond the typical Spielbergian fathers-and-sons-are-magical dross. Weirdly, the only time I ever see families depicted with any complexity during blockbuster season is in Pixar movies like Inside Out and the aforementioned The Incredibles; maybe nuanced portrayals of human beings is kid's stuff?

Or maybe the Fantastic Four would be better-recieved if they were on television. Special effects on a TV budget might be tough, but if you want to watch male and female characters interacting in a non-sexual way, you're much better off on TV than you are in a movie theater.

Maybe there's something else that I'm missing. Maybe the gee-whiz scientific appeal of early Fantastic Four comics has worn off through the years. But frankly, I don't think so. It's true that the widespread adoption of smartphones has changed the idea of what science fiction means, but a good Fantastic Four story should happily embrace new technology and offer bizarre new ways to surpass the technology we've already grown to rely upon.

Or maybe part of the problem is that the Fantastic Four, when you look deep down in their souls, are happy people? Any idiot can tell a story about a miserable superhero, but it takes a special kind of talent to tell an interesting story about good-natured, positive people. As sad as it sounds, miserable sells itself but happy, in the wrong hands, bores us to tears.

Rather than supporting yet another bad adaptation, I'd encourage you to track down the first 102 issues of the Fantastic Four and read them. Those stories might not resemble the world around you right now, but they sure do look like the world you'd like to see outside your window.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Kaijumax loses its balance

(Every comics fan knows that Wednesday is new comics day, the glorious time of the week when brand-new comics arrive at shops around the country. Thursday Comics Hangover is a weekly column reviewing some of the books I pick up at Phoenix Comics and Games, my friendly neighborhood comic book store.)

“We should not be tolerating rape in prison, and we shouldn’t be making jokes about it in our popular culture,” President Obama announced in a speech about criminal justice reform earlier this month, adding, “that is no joke. These things are unacceptable.”

He’s right, of course. In addition to being simultaneously cruel and facile, prison rape jokes are one of the last safe spaces for homophobia in popular comedy. And still, most comedies about prison or crime include at least one prison rape joke. What does it say about us as a society — especially a society with the largest prison population in global history — that we’re okay with this?

And what does all this have to do with comic books?

I’ve been reading and enjoying Zander Cannon’s new comic from Oni Press, Kaijumax, an ongoing series about giant, Godzilla-style monsters thrown into prison for trying to destroy cities. The “prison” is an idyllic island far from civilization, and the guards are Ultraman-like humans. The book demonstrates a bone-deep understanding of kaiju cliche and is packed with little in-jokes for people who’ve spent way too many hours of their lives watching adults in rubber lizard suits destroy cardboard cities.

But the kicker is that the kaiju all act recognizably human. These are monsters that worry about their families back home. They try to talk to the guards about life. They have regrets. The absurd premise smacks into the silly drawing style and the convincingly portrayed emotions, and the reader isn’t quite sure how to land at the end of each issue. It’s a pleasant kind of discombobulation.

But the latest issue of Kaijumax, issue #4, opens with a sequence that throws the story’s balance off-kilter. One of the kaiju, the buglike Electrogor, is bathing in a waterfall. Another kaiju, a lizard-looking monster with a scorpion tail named Zonn, approaches him and starts talking. Soon, Zonn is holding the struggling Electrogor down and piercing his carapace with his tail-stinger. The scene plays way too close to the reality of prison rape, and it flat-out ruins Cannon’s juggling act.

To Cannon’s credit, he doesn’t play the scene for laughs. And he shows the aftereffects of violence: Electrogor suffers from the violence for the rest of the issue. He’s delivered, crying and vomiting, to the island’s hospital where he tells the nurse, “T-terrible thing happened me.” This isn’t a Chris Tucker punchline tossed into the end of a buddy cop movie. But is it necessary?

In the letter column of this issue of Kaijumax, Cannon addresses the scene head-on. When a reader writes in to say that “the rape-ish jokes and pretend-[racial] slurs make me uncomfortable and I think there’s kind of a disconnect between the more cutesy art-style and pretty serious subject matter. Is this uncomfort [sic] and stylistic disconnect intentional or am I just too sensitive you think[?]”

Cannon replies,

I do intend there to be a bit of an uncomfortable edge to it. My hope is that it’s not too off-putting; I want the mismatch between the prison harshness and the monster-ridiculousness to be humorous, not mean-spirited. I acknowledge that I’m walking an edge with some of the call-outs to racism and sexual assault, but the book will always stay more or less in the PG realm; everything has a monster-movie equivalent. Hopefully the vague sense of unease it gives you now will be as bad as it gets. This issue is the one that I was (am?) worried about being slightly over-the-top in terms of what it was about, but I’m too close to it to know if it crosses the line. I don’t think so, since the nature of Electrogor’s assault is firmly in the monster-movie realm and veers very wide of what I expect would upset someone. All that being said, of course, not every comic is for everyone.

Clearly he’s put a lot of thought into this, but as a reader, I think Cannon is wrong; in this case, the scene plays out too closely to the kind of scenes we see on TV and in movies on a regular basis. By relying on the shorthand that entertainers have used for decades — the shower scene has played out hundreds of times in hundreds of ways — Cannon becomes a participant in a long and shameful tradition, even as he tries to transcend it.

Thursday comics hangover: Los Angeles is a magical place

(Every comics fan knows that Wednesday is new comics day, the glorious time of the week when brand-new comics arrive at shops around the country. Thursday Comics Hangover is a weekly column reviewing some of the new books that I pick up at Phoenix Comics and Games, my friendly neighborhood comic book store.)

I swear every month brings a new comic series about a paranormal investigator. It's one of the most overplayed ideas out there — a down-on-his-luck detective who bumps into demons or vampires or some other creature-of-the-week riff. The last iteration of the trope that I bought into was Paul Jenkins and Humberto Ramos's terrible series Revelations, which read like toothless John Constantine: Hellblazer comics. The paranormal investigator is the laziest way to present supernatural fiction, by giving us a jaded main character who explains everything to the reader. Why mess with this stuff if you're not going to try to instill a sense of wonder or horror or surprise in the reader?

The first time we meet our hero, Antoine Wolfe, he's on fire. But he's not really in any hurry to put himself out. Instead, he wanders around the back roads of Los Angeles, singing a Robert Johnson song to himself. We learn that Wolfe may (or may not) be immortal. At least, he seems to think he is. Wolfe's Los Angeles is packed with vampires and corrupt businessmen looking to hush up a murder or two. Around every corner is a goon waiting to knock him out and throw him in the trunk of a car. And Wolfe, who is African-American, understands that while the supernatural is dangerous, he's just as likely to get killed by a racist asshole with an axe to grind. The world is a dangerous place for him on multiple levels.

Taylor's art helps to sell the story's sunbaked Lovecraftian noir by staying simple and realistic. The cars look like cars, the people behave like people — Wolfe punches like a man who took a boxing class, in direct defiance of most ridiculous comics combat styles — and colorist Lee Loughridge keeps everything soaked in nauseating tones of green, so even the most ordinary panels seem to leak out a menace that's swirling just beneath the ink and paper.

Kot seems to know what he's doing here as he lays out the rules of Wolf's magic. We see a surprising array of supernatural aspects in the course of one single issue, but all the different menaces seem to behave similarly; magic is something that visits you and never leaves. It haunts people, including Wolfe, plucking at their sanity like a novice playing with a harp. It's hard to tell who's an eccentric urban mage and who's another schizophrenic, dumped on the street by a system that stopped caring decades ago. In other words, it looks a lot like real life.

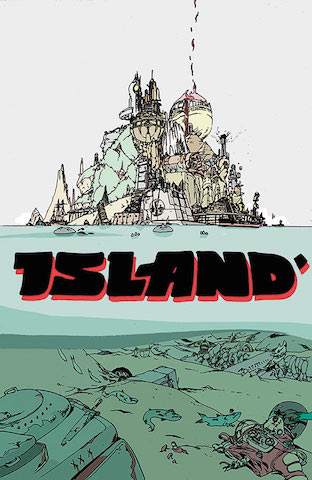

Thursday Comics Hangover: The possibility of an Island

(Every comics fan knows that Wednesday is new comics day, the glorious time of the week when brand-new comics arrive at shops around the country. Thursday Comics Hangover is a weekly column reviewing some of the new books that I pick up at Phoenix Comics, my friendly neighborhood comic book store.)

Serialized anthology comics are tough. They’re a pain to coordinate, for starters, and it’s hard to find an audience for a series of short, ongoing stories by a wide array of artists. I want to support anthology comics — Monkeysuit, a lively anthology back at the turn of the century was a particular favorite — but I have to admit that I often can’t be bothered when a new anthology starts up. Too much of an investment, too little return. For the most part, they disappear before they even really get started.

So I wasn’t planning to pick up the first issue of Island, the new anthology edited by Brandon Graham, but, hell, you try to ignore it. It’s a massive book for a monthly comic — over a hundred pages, squarebound, drawing in your eye the way light gets sucked into a black hole. The cover kneecapped me, with its intricate drawing of an island made up of many parts (a forest, a sci-fi spaceport tower, a temple, a sailing vessel straight out of Moby Dick moored to one side) and its moody blue-gray color palette. Nothing else on the stands looks like this. I had to have a copy because it was a beautiful object and sometimes it feels good to own a beautiful object. And even at $7.99, a dense, full-color comics anthology feels positively European, the kind of artistic endeavor you should want to support.

Like all anthologies, some of the stories in Island hit me harder than others. My favorite story was the one that opens the collection, “I.D.” by Emma Rios. A support group meets in a coffee shop. Rios tells her story in tightly cropped panels, claustrophic and tinted only in shades of red. Gradually, we see that the story is set in the future — people start discussing an interplanetary mining colony operation — and we learn that the support group is for people seeking body transplants. “My metabolism doesn’t allow me to be the man I want to be,” one character says, adding “I can’t stand being this weak anymore.” Just as the story starts picking up, something happens and then it’s To Be Continued time. It’s an excellent first chapter to a longer story, ending not on a shameless cliffhanger but at a point of change for the characters.

Comics author Kelly Sue DeConnick contributes a four-page prose essay about a friend who helped her become an author. “I was newly sober, which is a lot like walking around with no skin on,” DeConnick writes. The account is honest and raw and as earnest as DeConnick undoubtedly was, back in the days when she walked around everywhere carrying “a notebook and How to Write a Novel in 90 Days, the cover purposefully displayed."

Graham’s contribution is beautiful — just in terms of pure density, nobody draws a more rewarding comics page than Graham, with characters slouching around cityscapes packed with details and wordplay and corny jokes (on one street, a home is marked “Tori’s House,” with a tower down the street labeled as an “Observe a Tori.”) I’m not sure what, exactly, is going on in the story beyond a couple going to a restaurant that only serves whale, but I want to examine these pages, with their diagrams of cups of pudding and digressions about pornographic currency (“barely legal tender,” of course,) until a story makes itself obvious. With Graham’s work, the digging is the treasure.

The final story, a skateboarding (kinda) superhero adventure by an artist named Ludroe, is rougher than all the others — you get the sense that Ludroe is a graffiti artist who hasn’t quite adapted from Sharpies to a more nuanced tool — but it feels like an attempt to create an urban mythology. Maybe if someone tried to invent Marvel Comics in the New York City of today, it would look something like this.

So, yes. There’s no real connective tissue between these stories besides the fact that they appear between the same covers, and Brandon Graham decided to show them to you. Sure, the stories share some artistic flourishes — a European sensibility, a progressive vibrance — but they’re distinct works by distinct artists. Maybe that’s why Island works so well. It doesn’t try too hard to sell an aesthetic beyond pure cartooning ambition. In this case, that’s more than enough of a unifying theme to win my allegiance.