Thursday Comics Hangover: Thunderbolts and lightning

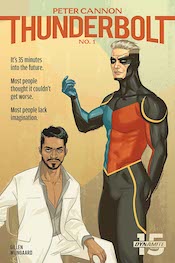

The first issue of writer Kieron Gillen's Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt was a solid-enough revival. Thunderbolt is a classic superhero who, unlike his peers published by Charlton Comics — the Blue Beetle, The Question, and Captain Atom — never really managed to catch on. In fact, when Alan Moore was forced to swap out the Charlton characters for thinly veiled analogs in the book that would become Watchmen, the Thunderbolt analog who played the villain of the book, Ozymandias, probably surpassed his original character in terms of name recognition.

Gillen overtly toyed with that Ozymandias connection in the first issue of Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt. The book clearly showcased many callbacks to Watchmen — the nine-panel grids, the Moore-inspired dialogue — and it pitted multiple versions of the character against himself. The book was interesting, but there have been so many riffs on Watchmen that it didn't really stand out.

In the second issue of Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt, though, Gillen breaks the damn comic. In a good way. One Thunderbolt crosses dimensions to fight an evil Ozymandias-like Thunderbolt by violating the 9-panel grid in a postmodern assault on Watchmen's rigid structure. Just to add to the book's self-referential flavor, Thunderbolt even notes before he breaks the panel borders that "This level of formalism is dangerous. We could lose some people."

Perhaps. But that kind of manipulation of the rules of storytelling is one surefire way to make me a fan of the book forever.

And then, in the third issue of Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt, which came out yesterday, Gillen breaks the book again, sending one Thunderbolt into a completely different genre of comic. (I don't want to spoil the final reveal of the book, which is one of the great last pages in recent comics memory.) It's pretty clear by now that Gillen is out to break the story and the form of comics again and again with every issue. He's doing more than just resurrecting an old character — he's forcing that character to come to terms with his own history in very literal terms.

Just as my regard for the story expands with every new issue of Peter Cannon: Thunderbolt, my respect for artist Caspar Wungaard grows, too. He's a very talented artist who can draw the hell out of a scene with two characters quietly talking, but Wungaard also can express some very complex concepts with a frightening ease. The concepts that Gillen unspools here are as complex as if I gave you a pen and a piece of paper and asked you to to draw the fourth dimension, or the passage of time. Wungaard makes the impossible look effortless.

As Thunderbolt himself notes, this kind of formal play isn't for everyone. Plenty of readers will find this series to be a little too impressed with itself. But anyone who is interested in the kind of broad information that a comics page can convey, and anyone who wants to know how hard you can push at the idea of a comic before it breaks forever, will be in heaven.