Born in chaos

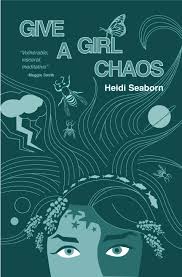

According to biographical materials supplied with her first poetry collection Give a Girl Chaos {see what she can do], Heidi Seaborn had a whole life as a traveling executive before she returned to poetry, in the form of a Hugo House class, just a couple years ago. After years of not writing anything of literary merit, the poems seemed to pour out of her.

Chaos is a collection that feels like a memoir. Most of the poems are built around a single moment — a swarm of butterflies surrounding Seaborn, say, who "flirted/with eyelashes/fingers/then flew to Mexico" and set squarely in a very specific place. These are shards of memories from a long and adventurous life.

Seaborn floats in the Dead Sea and stands in line for bad food in East Germany and travels by motorbike through Nepals. In between each poem, it's easy to picture a plane towing a thick red line from city to city across a giant globe, Indiana Jones-style. Part of the joy of flipping pages through Chaos is looking around to see where she's taken the reader now.

Seaborn has a poet's eye; she can find something remarkable in any given moment. You get the sense that even had she stayed in Seattle for her whole life — even if she never left city limits — she would have a book of intense personal poems to share with the reader, and they would be just as fascinating as this travel-heavy volume.

The language here is vibrant and, often, unforgettable. One poem begins with one of the briefest summations of childbirth I've ever read — but one that is as evocative as any I've ever read, too: "—awful scream/& I was done/& it was human." Later in the poem, she sees her baby with his "eyes open/flash of fish under water." The primal visions of childbirth, of making something from nothing, has rarely felt so vivid in so few lines.

It's perhaps a bit obvious to say about a book of poetry from an author who has only been writing for two years or so, but some of Seaborn's writing could use a little refinement. She refers to "playing opossum" in an early poem, for example, which is a cliched arrangement that lacks freshness. A poem about the ocean includes "scuttling" crabs and "the sea claim[ing] its birthright" and several other exhausted words and phrases. Poetry should never lean on those same words that everyone else relies upon for daily use; the whole point of a poem is to give us new toys to break and burn. In Seaborn's enthusiasm to finally land these poems on the page, she allows a few easily dodged cliches to slip through, and the book is the worse for it.

But these are not deal-breakers; Seaborn's poems take us places and expose us to thoughts we've never quite seen in a poem before. She gives us an argument that materializes in the form of gypsy moths:

Their dusty wings powder my hair

before drawing to the light.

Burning bright, singeing wings.

Who hasn't expressed themselves with hateful words that explode into dust and leave trails of fire across the sky? These are the words that hurt, from before they're spoken until well after they've stopped reverberating in the air. This is the power that Seaborn has — an eagerness to reveal new ways to see a world that feels as ancient as language itself. We're glad that she's, finally, arrived.