The blue-collar novelist

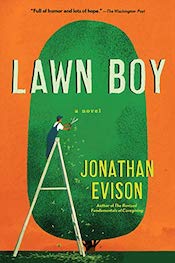

Last month, Jonathan Evison was on tour to celebrate the paperback release of his most recent novel, Lawn Boy. When Lawn Boy was first published, I praised the book on this site for its unapologetically blue-collar perspective. It's a novel that is unafraid to address class in Seattle, centering around a Bainbridge Island landscaper named Mike Muñoz who can barely hold his life together under the lingering threat of destitution.

Thanks to its raw class distinctions, Lawn Boy felt unique among all the novels I read last year. It was a book concerned with the same issues that your average American is most concerned about — mainly, work.

On the phone, Evison agrees with my assessment that Lawn Boy sticks out in the modern field of literary fiction. He says he's sick of reading a novel only to discover that "the whole conceit of the book will be structured around the seating arrangements of a fancy wedding in Cape Cod or something."

Evison continues, "I like reading books where people have real jobs." While blue-collar novels are scarce these days, Lawn Boy isn't the only example: Evison praises Northwest novelist Pete Fromm's latest book, A Job You Mostly Won't Know How to Do, about a carpenter whose wife becomes pregnant with their first child. "It was just so refreshing to read about a guy swinging a hammer and hanging some sheetrock," Evison gushed over Fromm's book. "People with real problems, you know?"

So why are books about ordinary Americans so hard to find? Why are so many novels about people of means? Evison says the "wealth disparity" in books on fiction shelves "speaks to the kind of people that are writing them. In order to break in to publishing, you'll have more of a chance if you're from some kind of money."

And reading has become a pastime for the privileged, too. "I think it's hard to get on the radar of working class people," Evison says. "I think populist fiction is kind of dead." But now that his book is in a more affordable format, "one of my hopes for the paperback is that it can reach a more egalitarian audience," he says.

Evison has worked more than his share of blue-collar jobs — including a stint as a landscaper — but now he's that rarest of beasts: a blue-collar novelist. He doesn't supplement his income with a tenured teaching gig at a prestigious university or a string of high-paid teaching gigs. Novels are his career.

So what's next? "I feel like I'm still learning, and that's the most exciting thing. I'm writing two books right now that I feel are the best things I've ever done." His latest novel is an epic story from multiple perspectives that evokes his earlier Pacific Northwest dynasty novel West of Here. "So much of the book I'm writing now makes me feel like West of Here was on training wheels."

Evison explains, "I've developed so many more tools" to help capture a huge story with an enormous cast. "Now I feel like I've got enough experience. It's kind of like an older ball player where the game slows down and can kind of see it unfolding and they can anticipate better." When you approach writing as a craft — a job that you need in order to survive — you learn how to improve your art without losing touch with the reasons why you're writing in the first place. It's a lesson that most of the the publishing industry could stand to learn.