Kissing Books: Characters exist to be thwarted

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

There’s a famous story they tell about Alfred Hitchcock, explaining the difference between surprise and suspense. Two characters sit at a table, chatting—when suddenly, the bomb beneath the table goes off!

That’s surprise.

Suspense is what you get when, first, the director shows you the anarchist planting the bomb beneath the table, then lets you bite your nails watching those same two people chatting in blithe ignorance of the threat, while the clock slowly ticks down explosion-ward.

The characters themselves are still surprised, in the second scenario. But the viewer has more information, and a fuller sense of what is actually going on in the story.

Hitchcock’s example frames dramatic tension in terms of danger, dread, and a countdown clock because those were his tools of choice. In romance, what we have is people. Hearts and hands and a few stickier bits. Sure, there may sometimes be other risks—there’s the whole subgenre of romantic suspense just for that kind of game, in fact—but instead of Hitchcock-style suspense I’d like to argue that the primary dramatic tension that fuels our genre is expectation.

Expectation is an end point. It’s a goal, that the book is driving toward, or a result, that the story’s machinery is designed to produce. And just like the Hitchcock example, the characters can’t know where we’re going, and the reader must know.

Romance characters exist to be thwarted, poor souls. They almost never get what they say they want at the start of the book. How many times do we see heroes state that they just want a string of casual partners, so as not to interfere with the safe, predictable course of their lives? How often do heroines insist they’ll worry about their love life later, right now they just have to save the small business they’re trying to get out of the red? Readers show up knowing the main characters will get knocked down and turned around and provoked and worn threadbare by emotions and attractions they’ll fight against for most of the space of the text.

We show up for this because we expect they’ll end up better, by the end. Better people, better partners, better citizens of whatever world they inhabit. We require that happy ending. We demand it as a right.

Reading tons of romances, over the course of years or decades, fine-tunes expectations even further. The genre, like any genre, rewards repeat engagement—you start to notice narrative conventions and trends, and the kind of moments that look like nothing special to an outsider, but which to authors and frequent readers might as well be stages with spotlights burning down upon them.

For instance: first kisses. The first kiss in the first romance you read is a singular experience. The first kiss in the fiftieth romance you read? You’re going to have a more complete sense of the many ways that first kiss could go–and the choices an author makes will tell you more about that story than simply the words on the page. You might even notice what an author doesn’t say.

You start to recognize the machinery of the story. And you start to select for the mechanisms that gives you, personally, the most satisfying result.

Longtime romance readers can get more granular about what they’re looking for than just about any group of readers you’ll ever see: fake dating, a good grovel, hurt/comfort, marriage in trouble, secret baby, enemies to lovers, opposites attract, amnesia, road trip, pining, fated mates … If you try summarizing or recommending literary fiction in this plot-centric way it comes off as painfully reductive (“Moby-Dick is about an intense sea captain obsessively hunting a white whale”), but that’s because the definition of literary fiction is: the genre that does not make you any specific promises before you start reading. Literary fiction is the genre of surprise.

Romance, though, tells you what it’s going to do. Like a stage magician, pledging to pull a rabbit out of an empty hat. You know it’s not real. You know there’s a trick. And when the rabbit does appear, it’s not surprise that makes your heart race and your eyes widen.

It’s satisfaction. Expectations achieved. A promise kept.

The story is a fiction, but what you feel is real. It’s the greatest magic trick I know (and the only one I’m equipped to perform).

This month’s books are all exceptional examples of character expectations being thwarted: two contemporary Pride and Prejudice retellings, two historicals with working heroines, and one dazzling m/m romance set in the halls of global political power. It’s safe to say none of the characters in these stories are prepared for the futures that await them.

But the reader only smiles, and sits back, and anticipates the journey.

Red, White, and Royal Blue by Casey McQuiston (St. Martin’s Griffin: contemporary bi m/m):

This queer romance between a stiff British prince and the impulsive son of America’s first female president is one of the buzziest books of the summer, and no wonder. Like Alex, our American hero, this book has heard about this thing called subtlety and wants absolutely nothing to do with it. If you’re looking for sparkle, for wisecracks, for high-stakes international forbidden lust erupting between two people who are forced for publicity reasons to pretend they don’t absolutely loathe one another, you’re in exceptionally good hands.

But subtlety isn’t the only kind of complexity: this book builds three-dimensional characters and reader-angst in a maximalist way, by sheer accumulation. The more you read, the more you feel—I was openly sobbing at the end, to the point where the mini-dachshund bounded up to make sure I wasn’t hurt. Alex is a mesmerizing combination of discipline and impulsiveness. Henry, our royal prince, is by turns perfectly dry and deeply vulnerable, a tweedy type whose formality masks a wicked sense of humor and poetry. Their connection is electric, and irresistible, and unfolds with a remarkable view of the dizzy, dazzling hedonism of youth. If I could attend any one of the parties in this book I could die a happy woman.

So I liked it a great deal, even if parts of it made me wince a little when they poked my own particular sore spots. Alternate history that retcons 2016—which this most definitely is, since our hero’s mother won her first term in that year—can be a bit of a mixed blessing when you are living in our much, much shittier timeline. This book is a political semi-fantasy in the style of Parks and Rec, or The West Wing, neither of which I’ve been able to rewatch since 2016. The author’s note clarifies that McQuiston wrote it partly out of her need for escape. My own escapism, alas, has to be much more removed from the circumstances that make it necessary; politics doesn’t feel distant enough for me to feel safe or triumphant or vindicated in that context, even within the bounds of a fictional storyline. Others definitely are different! We all find hope in different things! I am very interested to see where the author goes next!

Banter this good doesn’t happen just by accident, you know.

“This is idiotic,” Alex says, grasping Henry’s hand. The skin is soft, probably exfoliated and moisturized daily by some royal manicurist. There’s a royal photographer right on the other side of the fence, so he smiles winningly and says through his teeth, “Let’s get it over with.”

“I’d rather be waterboarded,” Henry says, smiling back. The camera snaps nearby. His eyes are big and soft and blue, and he desperately needs to be punched in one of them. “Your country could probably arrange that.”

Ayesha at Last by Uzma Jalaluddin (Penguin Books: contemporary m/f):

Pride and Prejudice retellings are never out of style in Romancelandia—see below—but despite some awkward moments this one is significantly more rewarding than most. I am resisting the temptation to write you a full essay on exactly what changes Jalaluddin made to the original story and how brilliant her overall vision is. I mean, placing a story about hasty judgments and self-knowledge in the context of present-day Islamophobia and misogyny and how those systems intersect is already Full Galaxy Brain, but there are so many more aspects of this book that made me gasp and stop and scribble notes about parallels and contrasts. It’s a little like the way Alyssa Cole’s Reluctant Royals series plays with fairy tales. The allusions aren’t just fan service, superficial nods to those who’ll get the reference: they’re weight-bearing plot structures that get things done.

For example: our less-than-impressive rejected suitor, Mr. Collins in Austen’s original, is transformed from a stodgy Anglican vicar into a very self-promoting young Muslim man named Masood who is, I kid you not, a life coach for professional wrestlers. He believes our heroine Ayesha has too much “repressed frustration,” and that she should consider channeling that into a signature move. It’s an absurd, impossible vision of good behavior—just Mr. Collins all over—but it’s unique and current and I died from sheer delight. And considering we know that our heroine Ayesha’s most cherished dream is to be a poet, and that her best forms of expression are verbal rather than physical, it’s clear instantly why this man is all wrong for her as a prospective bridegroom.

Ayesha’s poetry is also part of why hero Khalid is drawn to her. Mr. Darcy is possibly the most well-trod territory in all of romance, but traditional and devout Muslim Khalid is the sharpest take on Darcy I have ever seen. What does it mean to be perceived as cruel, or disapproving, when it’s because of your religious beliefs and how you express them? What happens when your heart comes into conflict with your beliefs and traditions? This book shines most when our main characters are sharing the page: it’s a very deep and true connection, though a very chaste romance—there’s precisely one fade-to-black almost-kiss.

One last point, because I’m going to be thinking about it for a while. In period-set adaptations of Austen’s book, the Mr. Wickham figures often come off as merely inappropriately sexy, rather than actively predatory. Wickham is something more than just a regrettable ex-boyfriend: he’s a threat to the Bennet family’s future. Modern retellings like The Lizzie Bennet Diaries and now Ayesha at Last translate this successfully by making the Wickham figure not merely a romantic rival, but also someone who trafficks in the worst aspects of online sexuality: revenge porn, coerced nudes, exploitative and misogynist sex sites. This book really puts the ick back in Wickham and gives us the proper emotional zing for the storyline.

There’s also a lot of undercurrents in this book about reputation, and consequences, and secrets, and forgiveness, which didn’t quite end up anywhere specific. But I sure did enjoy the journey, and it’s not one I’ll soon forget.

Ayesha walked Khalid to the door, and he took his time putting on his shoes. When he stood up, she noticed he had flour in his beard, and she reached out and absently brushed it away. His beard was soft, like spun cotton, and her hand lingered.

He clasped her wrist to stop her, and their eyes met—hers wide in sudden realization, his steady. Ayesha blushed bright red, embarrassed at violating their unspoken no-touch rule. He looked at her for a long moment, then gently, reluctantly, dropped her hand.

Some Like it Scandalous by Maya Rodale (Avon Books: historical m/f):

In some ways I am a very easy mark: I was sold on this book as soon as I heard it was based on the real-life Sorosis Club, the first professional women’s club in the United States. We have a brash chemist heroine, a golden-boy hero, and a great many female characters on the side, all chipping away at the foundations of the patriarchy.

It’s a fun historical take on gender and business and it works because the two characters at the center light the structure up like a lantern.

Daisy Swan has a sharp tongue and a sharper mind and knows she isn’t beautiful. But she still wants to feel beautiful, and knows many other women do too, and so she’s worked out a formula for a complexion cream that makes the skin luminous and dewy. She knows it’ll be a success if she has a chance to produce and sell it—but her mother is insisting that she has to marry immediately to stave off an unspecified family crisis.

But her surprise fiancé isn’t just anyone. He is Theodore Prescott the Third, heir to the Prescott Steel fortune, and the same gorgeous rogue whose cruel, catchy nickname for her made Daisy’s adolescence hell.

Theo is a beautiful butterfly of a man: he likes sparkle and scent and color, he’s good with fashion, he’s got a charmer’s silver tongue and he knows how to use it. He’s just my type, hero-wise. His father thinks marriage to the not-charming Miss Swan will settle Theo down and convince him to finally put his energy into the steel business; Theo would honestly rather do anything other than go to work in his father’s factory. So he and Miss Swan concoct a plan: they’ll pretend to agree to the engagement, then scheme together about how to bring it to a disastrous, irrevocable end before the wedding actually takes place.

We know how that goes, in Romancelandia. But even when they’re flinging insults at one another, Theo and Daisy’s chemistry is exceptional.

It’s rare to see a hero deliberately make himself the sidekick to a heroine, but Theo decides early on that his role is supportive and he gives it his absolute all. Daisy’s the one with the ideas; Theo is the one who helps make those ideas reality. Much of this book is less a critique of real-world capitalism and more a rejection of the way business/capitalism is gendered in the romance genre: the elder Prescott is all phallic steel skyscrapers and silver-fox manliness and ruthless opportunism, every alphahole billionaire trope in the book, right down to the tragically dead first wife. It makes him an astonishingly persuasive villain, and highlights Theo’s rare sweetness and softness, especially in the duke-infested realm of historical romance.

She opened her mouth to protest, but stopped. “As much as agreeing with you physically pains me, I must admit that you do have a point.”

“How magnanimous of you.”

“Look at you with the big words.”

“I went to Harvard, you know.”

“Of course I know that. Everybody does. Harvard people have a way of working it into conversation. I’m just not sure that you attended classes while you were there.”

“If this is your way of wooing me to your cause, I can see why you’re a spinster.“

Pride and Prejudice and Other Flavors by Sonali Dev (William Morrow Paperbacks: contemporary m/f):

A gender-swapped P&P variant, this one. Which means it’s our heroine who gets to be the arrogant, high-handed, high-class insufferable snob! It makes for a lovely change of pace.

Neurosurgeon Trisha Raje is focused, and ambitious, and secretly anguished by events in her past, and I loved her even when she’s demonstrably fucking everything up. Trisha is definitely a genius and devoted to her medical work even if she struggles with her bedside manner, her politically ambitious family, and pedestrian tasks like remembering to eat. Her lax approach to dining is one of the many ways she outrages DJ Caine, our British expat hero, an accomplished chef who worked his way up from nothing to a Michelin star—and whose sister needs a life-saving operation only Trisha can provide.

We’re at least six layers deep in melodrama here: there is just so much angst and anguish (content notes for multiple crash deaths, sexual abuse, multiple terminal cancer cases, burns, strokes, miscarriages—seriously, anyone who has a name has a Tragic Backstory, I’m not kidding). It means this book has some heavier angles that readers ought to know going in. Couple that with Julia Wickham, a white blonde chick with dreadlocks and a Ganesha tattoo who turns out to be one of the most bone-chilling villains I’ve seen in romance in quite some time (my point above about Wickhams and ick definitely applies), and this book is more pick you up and turn you inside out than frothy summer comedy. But in the expert hands of Sonali Dev, all the angst and anguish is worth it. (Also, my god, I could listen to DJ rhapsodize about food and flavor all damn day.)

Trisha Raje was without a doubt the most insufferable snob DJ had ever come across in his entire bloody life. He’d been the poor boy at a Richmond private school. He’d worked at a Michelin-starred place des Vosges restaurant for ten years. He’d seen far more than his fair share of self-important, overprivileged gits. But it had never bothered him. Not like this. Her snootiness didn’t just get under his skin, it chopped up every bit of pride he’d ever managed to gather up and flung it all over the place like a blender you forgot to put the lid on.

This Month’s Badass Labour Organizer Heroine:

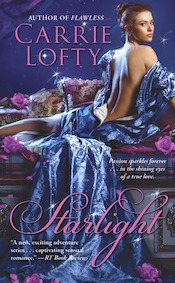

Starlight by Carrie Lofty (Gallery Books: historical m/f):

Our heroine Polly Gowan is no debutante: she spends her days organizing strikes and supporting workers at a 19th-century Glasgow cotton mill. There are pub jaunts, and football games in the mud, and clashes with the tyrannical power of the law. Polly’s father was a famous organizer, and she intends to carry on his work even as she slowly and grudgingly falls in love with the new mill owner hero (who’d much rather be studying the stars, but who has to make the mill profitable to keep custody of his infant son). Historical romance heroines definitely skew aristocratic, statistically—partly because it’s easy to find historical information about the aristocracy (preservation bias is heavily weighted in favor of the rich), partly because the romance genre’s progenitors were set among the gentry, and partly because a lot of the time readers want to escape into a wealth fantasy.

And while we all love a good historical gown description (some of us have even written whole romances about that, in fact!), more and more I’ve been searching out stories with heroines like Polly—or like the everyday shopfolk and servants in Rose Lerner’s Lively St. Lemeston series—or Cat Sebastian’s cranky radical bookseller. The people on the ground, doing the actual labor, turning the great wheels of history one working day at a time. The people we’d most likely have been, if we’d been born in past eras, no matter what the psychics say. They—we—deserve happy endings at least as much as the nobs do.