Kissing Books: Summer murders

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

Now that we’ve reached the height of summer, the long string of brilliantly sunny days, of course I’m thinking about murder.

There are plenty of overlap subgenres in the spectrum between romance and mystery: the lush and atmospheric Gothics, adrenaline-fueled romantic suspense, long cozy mystery arcs with a pair of sleuths who slowly fall in love across several books (Lord Peter and Harriet, Phryne and Jack).

And the point where all these genres connect is: trust.

Mysteries are built around the breaking of trust: secrets hidden and revealed, lies told, the sundering of the social bond where we constantly, implicitly trust one another not to just pick up a knife and start stabbing. The body in a murder is the symptom of rupture, and it must be dealt with: we must find out specifically who is untrustworthy, so we can go back to the comfort of being able to exist in the world without fearing one another. I often think about the aftermath of mysteries, the families and towns whose most devastating secrets have been laid bare to the eyes of strangers, the police, and the public. Some little old lady sleuths hit the landscape like a rocket and leave smoking craters in their wake (looking at you, Miss Marple, you absolute horror).

Romance, too, is about trust, though admittedly in a more positive way. Heroes and heroines learn to let go of their fears, to let their guard down, to open their hearts. It makes for a natural pairing with a whodunnit, which tends to make everyone less and less trustworthy until the final a-ha. Add to this the many times and places when there were laws against certain kinds of love relationships — such as, for instance, 19th and 20th century England, with Sherlock and Marple and Poirot and all the classic detectives of the English mystery tradition — and the origin of certain unfortunate clichés becomes clear.

Queer villains make a certain amount of sense when being queer makes one automatically a criminal.

What’s interesting is how reader trust works in romance versus how it works in mystery. Mystery authors aren’t trustworthy. You know they’re pulling a fast one, leading you down wrong paths, seeding the text with red herrings, obscuring the real killer as long as they can. You never really trust someone, mystery writers say. For enough money or love, people will do any number of criminal things.

Romance does the opposite. You know, positively and irrefutably, that the main characters will end up not only surviving the book, but existing happily together. You know they can’t be the killer — not the capital-K-Killer, though they may and often have killed in the past for the noblest of reasons — because that would make it a tragedy, and any romance author worth their salt would never.

So it becomes a rather complex bit of footwork, to show two characters slowly learning to trust one another, while everyone else around them grows more and more shady and suspicious. Two threads of tension, creating friction between them and occasionally knotting tight. Gothics, of course, push this nearly to the last page, like tightrope walkers working without a net. I find myself drawn most toward the cozies, your amateur sleuths and house party murders and small villages with awful mortality rates and overworked, eagle-eyed detectives. I like the puzzle-box aspect of solving a crime, without the looming dread and sexual threat that seems to accompany so much romantic suspense. (If I never read another scene in Creepster POV where a serial killer lusts after the heroine, I could die happy.)

This month’s books go heavy on the m/m: one midcentury mystery, one Prohibition paranormal, and one pair of contemporary baseball teammates. We’ve also got the best f/f sci-fi romance I know of, and a brand-new masterpiece that has really upped the bar for my expectations of gangster heroes in contemporary romance.

You know they’re gonna be good. You can trust me.

Hither, Page by Cat Sebastian (self-published: midcentury m/m):

There is a moment some ways into this queer murder spy-and-doctor mystery romance, where our spy (Leo) and our doctor (James) are having dinner and trying to understand one another. Leo is prevented from telling James the facts of his past (that Official Secrets Act is such a downer sometimes), but James only says that they can easily describe themselves without resorting to trivia. “I like to be useful,” he offers, as an example. Leo, meanwhile, struggles to do this, because he has spent so many years and so many jobs pretending to be someone he knows he’s not. It’s a lovely moment of mingled tension and introspection, a grace note to sweeten all the murder.

This is not a puzzle-box mystery, for those who like to be led into a twisty, deliberately crafted maze of a murder. There are more red herrings than not-red herrings, and the reader is tormented by characters obliviously waving around an absolutely key piece of evidence for a hilariously long number of pages. But the solid sense of place, a tight-knit community riddled through with secrets, a nation recovering from the trauma of not one but two world wars, that palpable miasma of what desperate people will do to one another when they feel their backs are against the wall … that we have in spades, as well as two suffering, struggling protagonists who are far kinder to one another than they are to themselves. If you’re in the mood to spend some time in the byways of Murderville, England (I’ve been visiting for months now), there’s nothing better than this.

James wanted his house to be a safe place he could have a life with someone. He hadn’t said as much, but it didn’t take a mind as sharp as Leo’s to figure it out. This house only made sense if there were someone to share it with. There was a superfluity of furniture, for one: an extra chair by the fire, too many hooks by the door, a bed too large for one man. Even the wardrobe had all the hangers pushed to one side, as if waiting for another person’s coats and trousers.

Winterball by Holley Trent (self-published: contemporary m/bi m):

Summer always puts me in the mood for baseball romance, and this short and snappy treat comes complete with Holley Trent’s signature snark and sizzling kink. Bart is an aging catcher with aching knees; his days in the majors are long gone, and his days in the minors are soon to follow. Evan is a hotshot young pitcher on the rise, gorgeous and cocksure (in every sense of the term), but high-strung as a trained thoroughbred. He’s come to depend on Bart’s cool control on the field, and lately he’s started to think that maybe that cool control might be what he needs in the bedroom as well. Bart, meanwhile, keeps his overwhelming lust for Evan on a tight leash because he doesn’t hit on (supposedly) straight teammates. When a weekend at an invite-only kink ball finds them paired up and sharing a room (it’s Romancelandia: roll with it), we get to see them finally making good on all the growly innuendo and filthy eye-fucking.

I started out writing novellas, and used to joke that I plotted those books all the way from A to B. This story is just like that: it knows what it needs to do and wastes no time doing it, like a good fastball with just the right amount of heat. Bart is the kind of grouchy, tired older hero I’m always instinctively rooting for (see also: S.T. Maitland from Kinsale’s Prince of Midnight), and Evan’s irrepressible brattiness adds a nice levity, like the twist of citrus in a well-mixed cocktail.

He didn’t know about all men, but Bart was certainly pushing all the right buttons. What Bart had said about who Evan belonged to might have been said as a tease, but Evan wished it were true. He did want to belong to someone. Not just anyone, but his catcher. Bart would never drop the ball on him.

Trashed by Mia Hopkins (self-published: contemporary m/f): At times such as these, reading a book like this, it feels important to choose words with care. The word I most want to use about this absolute masterpiece of a contemporary romance is: visionary.

Mia Hopkins has gifted us with the story of a good girl chef, Carmen, and a bad boy gangbanger just out of prison, Eduardo “Trouble” Rosas. They shouldn’t want anything to do with one another, but they keep coming back for more, though they can’t quite say why. I am excessively picky about my gangster hero’s, but Eddie is easily the best one I’ve ever read, hands down, bar none. He’s not romanticized or whitewashed or fetishized in the way such heroes often are: he participated in a bad system, and he has to cope with the consequences and the trauma and the fallout. The story is careful at first, slotting characters and stakes into place one at a time, keeping the reader hooked with evocative descriptions (for instance: a gang leader’s grey Monte Carlo sedan pulling up to the curb “like a lazy shark”—the writer part of me writhed with wishing to have written that).

About halfway through—at least, that’s when it happened for me—all those shiny, colorful bits come together and what looked like fragments of shattered glass become a whole rose window, deliberately laid out and brilliant.

And you go breathless with awe.

This is a book that delves deep into our need for community and what that makes us do for and to one another. It’s the same question The Good Place asks so insistently: What do we owe to each other? We see the trials and temptations of gang affiliation and prisons, but also the systemic damage wreaked by gentrification. We see the strengths of good communities: tight-knit neighborhoods and family and friends and communal gardens and small local businesses and well-run kitchens. The people we’re closest to can hurt us the most, but they’re also the ones who make life worth living at all. This book is about people banding together to solve problems that would overwhelm any one person—it’s about putting together a future by refusing to let the evils of the world beat you down. And to see a book this focused on connection, but which also keeps the reader entirely inside the hero’s head is kind of … kinky? It’s like the author’s using POV like a set of leather restraints: not being able to move away from Eddie’s perspective magnifies every sensory detail of his experience. His laconic, introspective voice is quiet but potent. We fall in love with Carmen because Eddie can’t help but love her. In his vision, she glows like a star.

This is not always an easy read. There are abuses past and present, moments of genuine, searing pain. Eddie fucks up a lot, trying to keep his balance in the whirlwind, and the ending chapters are one punch to the gut after the other. And then, at the end of the fight, when you’re splayed out on the concrete and the rain is washing the blood thin and you think you can’t make it one second longer … the sun breaks through, and the light rushes in, and your chilled heart blooms with the warmth.

Don’t miss this one, folks.

Spellbound by Allie Therin (Carina Press: historical m/bi m):

In my youth, one of my favorite books was Patricia C. Wrede’s Mairelon the Magician: in Victorian London, an orphan girl dressed as a boy gets taken up by an aristocratic magician accused of a theft he didn’t commit; together, they solve the theft, prevent a great magical crime, and begin the orphan girl’s magical training. (The less said about the romance between the two in the sequel, the better—it was fun when I was sixteen but now that I’m closer to Mairelon’s age I find myself appalled.)

This book is like the queer, age-appropriate, New York Prohibition-set version of that and I am so delighted I could shout. With the added bonus that our upper-class hero, Arthur, so confident and privileged and strong, has no magical talent whatsoever.

Meanwhile our urchinish Rory, struggling and suspicious and vulnerable, has immense magical gifts he’s only barely learned to control, and a smart mouth that doesn’t hesitate to tell anyone to fuck off when he feels cornered. It goes a long way to smoothing out the power imbalance between the two. Meanwhile we’ve got historic New York, marvelous side characters, and a real magical threat that needs to be stopped. It’s textured but not terribly complicated, just the kind of historical fantasy sparkler that I adore the most. Perfect escapism for lazy summer days by the water, or long trips, or to read by a fire in the middle of the woods.

Rory was suddenly angry. “Now you’re the one talking crazy. You’re so convinced you gotta be alone, I bet you don’t let anyone try.”

“You don’t understand —”

“If you took a chance, if you let people in, there’d be a war for you,” Rory said hotly. “I’d fight an army if—”

If I thought I could have you. He snapped his mouth closed before the rest of the sentence escaped. Geez, he had to shut up.

This Month’s Queer Disabled Heroine of Color (In Space!)

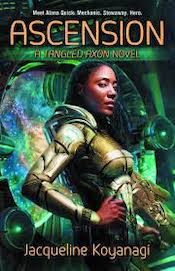

Ascension by Jacqueline Koyanagi (Prime Books: science fiction f/f):

I swear I thought I’d told you all about this book before. I know I wrote a whole big thinky essay about it, which then to my utter surprise and delight got included in this anthology. I mention it on Twitter whenever I think about sci-fi romance, or disability in romance, or queerness in romance, or queerness in science fiction, or poly relationships in romance and science fiction. It is a profoundly good, profoundly queer, thoughtful portrait of women and others falling in love with one another and also starships. It asks hard questions about the body and the soul, and what kinds of sacrifice are good and which are villainous or catastrophic. It does all this while being an absolute ton of smart, gorgeous fun.

It is a perfect book and why are you not reading it right now? Alana Quick is a starship mechanic with a chronic pain disability: her need to be attuned to her body and its fluctuating health means she has an edge diagnosing problems with ship systems and engine malfunctions. There’s something almost literally magical about the way ships and machines are discussed in this story, and it hits that perfect glowy space opera sweet spot even as it’s being utterly devastating about illness and the inevitability of death. I’ve never felt so hopeful about the hopelessness of existence than I was at the end of this book. Ordinary human mortality somehow came to feel like a moral triumph. It’s a total rush, a necessary punch to the gut, a book that will haunt you long after you close the last page.

Dirt doesn’t feel right on the heels of someone born to be in the sky.