Celebrate National Poetry Month like an introvert and an extrovert

National Poetry Month was eclipsed by the plague of it all this year. What would have been a solid month of readings and public art and parties has given way to streamed events and canceled book launches and other pandemic-era disappointments.

The best way to honor National Poetry Month in the middle of a pandemic, to the best of my estimation, is to sit with some poetry books and use them as lenses on the world — to really try to think like a poet.

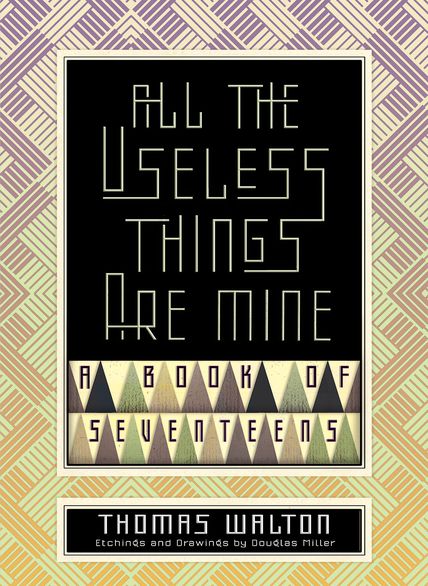

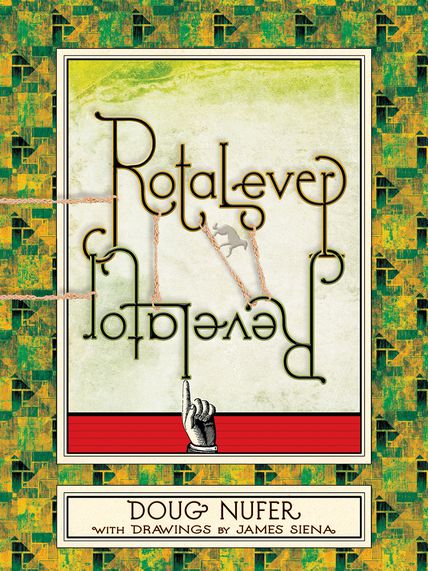

I've been spending the month with two new releases by Seattle poets from local press Sagging Meniscus's Shorts line of pocket literature: All the Useless Things Are Mine by Thomas Walton and Rotalever Relevator by Doug Nufer.

Useless is a collection of poetic aphorisms championed by Walton called seventeens — 17-word sentences or collections of short sentences totaling 17 words. They're sort of like haiku, and like haiku the best examples of the form are meditations on the mystery of nature:

Nobody tells you the morning light is blue, bluer than the bluest blue moon. Nobody says that.

and

The storm passed and when it did it left the plum tree bedazzled as a spinning child.

Some of the seventeens are a cross between a one-liner in a standup comedy routine and a zen koan:

Little man in enormous truck shouts: I don't have a Napoleon complex! . . . it's much bigger than that.

Our babysitter drinks whiskey and is usually late, but we don't mind, we don't have a baby.

Walton told me that he'd prefer readers dip into and out of Useless, not sprint from front cover to back. Authors are not always the best at determining how to enjoy their own work, but in this instance Walton is correct: you have to keep the book close for a while, flip around, and see what sticks.

No matter which of the seventeens most appeal to you — the magisterial or the witty — you will likely find yourself affected by this book: you'll start to see the world as a series of potential seventeens, just waiting to be written. When you leave your quarantine for the world outside, your eyes will scan around, trying to find pieces you can frame within seventeen words. It's a constraint that is at once a manageable size but also capable of inspiring revelatory moments.

Every Doug Nufer book has its own high concept, a constraint that effectively becomes the plot, the narrative drive, of the project. Here's the publisher description of his latest:

Rotalever Revelator is a book made from words that spell other words backwards: a giant palindrome that contains poems about geography, dams, swamps, celebrities, eponyms, and the news...Flip the book over, and you have Rotalever Revelator: the same sequence of letters, differently divided into words and punctuated.

This isn't the first time Nufer has made a flippable book — his Ace Doubles homage The Mudflat Man/The River Boys had the same basic format — but this time Nufer really digs into the idea of what it means to have a book with two separate but equal front covers, first pages, and so on. Revelator Rotalever is a mirror image of Rotalever Revelator but also the two books combine into an ouroboros of language, a long palindrome with two beginnings and two ends, or perhaps no beginning and no end.

Nufer writes himself into the work this time, shouting his own name into the echo chamber on multiple occasions. The first two words of Revelator Rotalever are "Nufer snips." The last three words of Rotalever Revelator are "...spins re: fun." Nufer snips and spins the language. Why? For the fun of it.

Here's something that many of you have probably encountered at least once or twice in the past few weeks: when you're on a video call on your phone and you walk into a room where someone else is on the call on their computer, the two video chats begin conversing in a weird loop of screeches and gulps that gets louder and louder until someone has to end the call to silence the feedback. Nufer has made two short books that are deep in conversation with each other in that way, a closed loop of language that references itself and satirizes itself.

While you can take Useless out on the road with you, pulling the world through the frame of the book, Rotalever is the kind of book that makes you want to stay inside and wrestle, flipping back and forth to see how it speaks to itself. I got my copy a week ago and it's already battered beyond repair — spine broken, pages bent, edges scuffed from turning and re-turning and returning in a palindromic journey to the end of the beginning and the beginning of the end.