Book News Roundup: Iceland comes to Seattle this week

- We caught wind of this event too late for tomorrow's reading calendar, but it's too cool not to mention. The 2016 Taste of Iceland festival is happening this week, and it features a free reading at KEXP's brand-spanking new headquarters (472 1st Ave. N) on Friday, October 14th. Iceland is one of the most literary nations on earth, with more authors per capita than anywhere else, and it's got a long, rich and unbroken tradition of literature that you should learn more about. Here's a description of the event:

...The event will blend together literature, history, and music, starting with a discussion by renowned author, Guðmundur Andri Thorsson on “Paper Vikings: Past and Present.” Thorsson will lead off the event with a lecture at 6 pm on Icelandic literature followed by a lively Q&A panel hosted by The Elliott Bay Book Company and Seattle City of Literature.

At 7 pm, Örnolfur Thorsson and Dr. Gísli Sigurðssonn, will take the stage to showcase both of their works and participate in a panel discussion on the Icelandic sagas and Norse mythology. Immediately following the panel discussion, Reykjavik Calling stars Fufanu and JFDR will treat the audience to a live “Rímur” performance! A ríma is an Icelandic epic poem written in any of the so-called rímnahættir

Last Friday, the Bureau of Fearless Ideas announced that their new executive director will be Andreas Herbst. The outgoing ED and founder of the BFI, Teri Hein, wrote in a post that Herbst was most recently "director of Seattle Goodwill's nonprofit job training and education centers," and that he has worked closely with Dave Eggers' Valentino Achak Deng Foundation. We look forward to meeting Herbst in the very near future.

Two Sylvias Press just announced the winner of the 2016 Two Sylvias Chapbook Prize. Congratulations to Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, whose book Arab in Newsland will be published by the Kingston press in the coming months. We published an amazing poem by Tuffaha, "As In," over the summer.

The very exciting new online poetry publication gramma just published three wonderful new poems by Seattle's own Sarah Galvin. Go check them out, and be sure to click around gramma a little bit while you're there.

Seems that some authors aren't being credited for pageviews on Amazon's Kindle Unlimited program, according to Nate Hoffelder at The Digital Reader. This is a big problem because on Kindle Unlimited, "Amazon pays not based on sales but on the number of pages read by KU subscribers." Hopefully those writers will get the money Amazon owes them.

Five Alarms

Vancouver has an

approved fireworks

competition.But here the

only permitted explosions

are gas leaks.Through Greenwood’s

skeleton

(this neighborhood

always burning down)with my sister, the arted-up

boarding for windows of still open

businesses.Block long fenced off gravel

pit where I once ate gyroswith my nephew. (this neighborhood

is always coming up) The

Cyclery, the reading center are Causes,

rally points, easily raised funds to moveahead. The family

owned coffee shop

not so much, just another,plus,

they live a few miles south and

their house is being destroyed

to make way for an oncoming train

station.

Let The Help Desk help you with your NaNoWriMo novel

November is fast approaching, which means it's time for National Novel Writing Month. Our own advice columnist, Cienna Madrid, is no novice when it comes to NaNoWriMo, and so she'd like to offer up her column for writing advice for the entire month of November.

Feel free to ask Cienna any questions about the process of writing (Do you have a character who's just not doing what she's supposed to do? Does your dialogue sound like it's been crafted out of cheap tin?) and about the etiquette of writing. (Should your loved ones be jealous that you're reserving a couple hours a day to write all November long?) She's looking forward to helping you write 50,000 pain-free words in the month of November. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

30 years of an amazing local publisher

Sasquatch Books is turning 30! They came to celebrate with our readers. From Best Places, to Book Lust, to amazing cookbooks like A Boat, A Whale & A Walrus, Sasquatch produces high-quality, high-interest books right from the heart of Seattle.

Go to our sponsor's page to look at an amazing timeline of their achievements over 30 years, and congratulations, and continued success, to this beloved Northwest company.

It's thanks to sponsors like Sasquatch Books, and readers like you, that we're able to keep the pixels lit up here at the Seattle Review of Books. We've just released our next block of sponsorship opportunities. Check them out on the sponsorship page, and grab your date before they're gone.

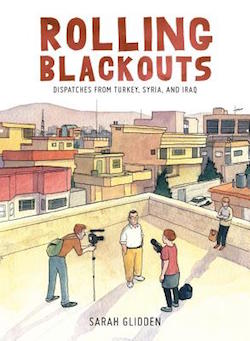

You need distance to tell a story: talking with Sarah Glidden about comics journalism

On Wednesday, October 5th, I interviewed Sarah Glidden about her excellent book Rolling Blackouts at the Elliott Bay Book Company. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

PAUL CONSTANT: So you traveled to the Middle East with reporters from the Seattle Globalist in 2010. Over the next few months, they published reported pieces and videos and photo essays. And now six years later, here comes your book about the experience. I was wondering if that lag signifies a drawback of comics reportage to you, or if you think there's something comics journalism can do that other forms can't?

SARAH GLIDDEN: If you're going to do a big book like this, you definitely want to pick a topic that will have a shelf life, that will last longer. When we went out to do this book, I wasn't thinking, "I'm going to make a book about Iraqi refugees." It was, "I'm going to make a book about journalists and about how journalism works." I figured within the next five years or decade, the way journalism works wasn't going to change that drastically — and I don't think it has.

Those topics are still the same, but also I think that when it comes to the things that they were reporting on, and then that I was reporting on, the facts on the ground might have changed and those regions have changed — definitely, Syria has changed — but that doesn't mean that what they were reporting on then didn't happen. It still happened. Maybe it's less of-the-moment journalism, but it's still something that these people went through, and it's still a time in the history of that country that's important.

I think it's important to us as well because one of the reasons the journalists I was with wanted to report on Iraqi refugees was that this was already seven years after the invasion of Iraq and the U.S. had kind of moved on a little bit from that war. The war was winding down and Obama was elected, so there were just other things to think about. The fact is, for the people who were affected by that war over there, that stuff still mattered and was still important.

This is a very thoughtful book about both journalism and about that specific situation and I don't want to get too deep into process, but I do want to know how much of the finished book you had envisioned right after the trip, and how much of it came about in the process of writing and drawing?

There were certain moments that, as they were happening, I was like, "Oh this is definitely going to go in the book." Like the first page of the book was one of those moments were I was like, "Oh wow, this is a really strong moment. I definitely want this to be in [the book]." There were also some funny moments, like the second page of the book, where I thought, "Okay, this has got to go in there. It's just too good."

There were some things that happened that I had that same feeling, and then when you're working on the book you realize that they don't actually have a place there. Then you have to do the whole "kill your darlings" thing and let them go. The book took a long time, and it wasn't just because it takes a long time to draw and paint everything. That, for me, is some of the stuff that takes the least time.

Just sorting through all the material I had and figuring out how to tell this onion of stories — there's the story of the people reporting, and the stories that they’re reporting on, and then the stories of how those things interplay — that was a very complicated knot to untangle.

I was recording everything, so almost all of the dialogue in the book is from recordings that I took. The first year when I got home, I was really spending most of my time transcribing everything, because I thought that I needed to transcribe everything. I kind of needed to figure out what the voice of the book was going to be and how much my character was going to be in it. There was a whole part where we went to Lebanon and I cut that whole part out because it really, in the end, didn't have anything to do with the major themes of the book.

Are you more comfortable working in books as opposed to shorter pieces published in magazines and things like that?

I don't know about comfortable. This was a very uncomfortable thing to work on. A lot of it was material that felt almost over my head in a certain way. I felt at times like, "I'm not qualified to talk about journalism," or, "I'm not qualified to talk about the war in Iraq because I'm not an expert on these things." If you give yourself enough time, you can force yourself to talk about anything.

I do like working in short pieces, but, for me, length is really comfortable because you can go on and on. For me, doing like a two-page comic is the hardest thing because you have to get a whole bunch of information into a very short space and you don't want to put too much text in the panels because people's eyes get tired.

After working on this for so long, I feel like it's going to be a while before I start another book. I'm probably going to work in short pieces for a while now.

It's October 2016, so we've got to talk about the orange elephant in the room. Your book's about Syria and refugees and I wonder if you have any special perspective on the election and Donald Trump because of your experiences?

I will say that the thing that makes me the most angry that Trump says, and that a lot of other politicians on his side of things talk about, is using the refugee crisis to stoke people's fears about terrorism and saying things like, "We don't know who these people are and they're not vetted properly." It just makes my blood boil, because we spent a lot of time talking to refugees and talking to people at the United Nations about these refugees. I spent five years really looking into refugee law and how all that stuff works. Now I know that [what those politicians say is] the opposite of true. There's almost two years of vetting that refugees go through before they come here. They don't bring single men ever, they bring families or they bring widows. They bring the most vulnerable people first.

Really only 1 percent of registered refugees ever make it to the U.S. anyway. When I hear people using refugees to get people all riled up and afraid of terrorism, it's so sad to me because we should be letting more people in, not fewer people. We made all these promises to translators and people who worked with soldiers in Iraq, and we haven't let those people in yet. For me, that's my little tiny corner area of expertise when it comes to this election. When I hear Trump saying things about refugees, it makes me upset. The rest of it I feel like I have no control over whatsoever. I'm just going to fill out my ballot and mail it in and hope for the best, I guess.

One of the most striking scenes in the book for me is when you're all talking about protesting the war and you drew yourselves as younger protesters at an Iraq War protest. One of the things that you're talking about is whether you could have done more to stop this. With that in mind, I wonder if you think there's anything we could have done to have stopped this political situation we’re in right now?

I remember when we were protesting the war. [Globalist reporter] Sarah [Stuteville] and I had very different ideas about what were good protesting tactics. I would see people smashing windows and be like, "That's not good because that will make people think that we're bad. That's not helpful." Whereas she wasn't going to go out doing those things, but I think she understood better that we need lots of different kinds of tactics for protesting.

I think I've come over to that point of view a little more now as I get older and you have seen protests that work, like at the pipeline in North Dakota: people really getting in there and doing direct actions, and things happened because of that. At the time, I really was of the mind, "We did all we could. We went to protests." Who knows? There have been governments that have been toppled from people filling up a square. Just yesterday, Polish women all went on strike to reverse an abortion law.

Maybe we just didn't go far enough, I don't know. I do think that is the job of young people: I think the older you get, the less you can just leave your job and the more you think about whether this is a good idea or not. When you're in your early 20's or you're in high school, yeah, it is your job to go protest. And maybe a little bit later, you become a reporter.

Is your work going to continue to be focused on the Middle East or were the first two books just the way it happened to land?

It was kind of a coincidence. When I was working on [Glidden’s first book, How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less], I talked to the Globalist — I said, "Next time, you guys, when I'm done with this book and it's your next trip, then we'll do it together." It just so happened that it was for this trip. If I had finished a little bit earlier, I probably would have gone with them to Pakistan. If it had been a little later, I would have gone with them — they did a journalism series in the Ukraine called “Generation Putin.” I would have gone on that trip if I had finished later. It just so happened that it was this trip.

I'm glad that I went, because from doing a book about Israel and Palestine, I did have a little bit of context for what we were seeing and who we were talking to. I think for my next works, I'm going to try to stick a little closer to home. I think there's plenty going on here.

You moved to Seattle last year — almost exactly this time last year I interviewed you for the Seattle Review of Books as a new Seattleite. I think it's been kind of a banner year for comics in Seattle, and you seem to be a big part of the community already. I was wondering if you could talk about your perspective as a newcomer?

We've been friends with [Short Run co-founder] Eroyn [Franklin] for also a really long time. So when I would come here and visit, Eroyn introduced me to the comics community. I remember one of my first visits here, I went to the Fantagraphics Store in Georgetown and I have a picture of me in front of the store with a little bag because I bought something inside. I was really excited because between Fantagraphics and Drawn and Quarterly — Montreal and Seattle, those were the two indie comic centers.

When Eroyn started doing Short Run a couple years ago, I remember seeing it go from something small she was talking about to a festival that people who I knew, who didn't know them, were talking about — and they were talking about it being one of their favorite shows.

It was exciting coming here and getting involved with that. I'm on the board now so I got to help them figure out which international guests to bring. It's been nice coming to a new place, but feeling like you have a community and that you're helping be a part of it.

It’s a good thing that there’s Short Run because otherwise you might not see other cartoonists. It's a job where you're sitting at home, usually, and you're working alone. I was working on this book until March or April and there was a couple months there where I couldn't go out at all. I think it's good that there's something like Short Run that makes these events — not just the festival, but also there's Summer School and stuff like that — because otherwise I think cartoonists are prone to just staying inside and not socializing very much.

When you lived in New York, you were part of Pizza Island, a cartooning community, and pretty much everyone from that group is sort of blowing up now: Kate Beaton and Lisa Hanawalt and Julia Wertz. Did you feel like it was something special at the time? It's almost like a rock group, going off in your own directions. And if that analogy is correct, are you Wings?

It really did feel special. I think we kind of knew it. It happened by chance: I was friends with Julia first and then we got to know Lisa when she moved to New York and Domitille [Collardey] was — you know, she came from France, and she was dating a musician that I knew. Then I got to know her and then at that time, we decided just to get a studio.

We kind of knew Kate from around the way and Kate knew Meredith [Gran], so we all ended up together. I don't think we really understood how special it was until people started writing articles about us. I think people made a big deal out of it being an all-female cartoonist studio. We didn't go out to make an all-female studio, it just happened that everybody was a woman.

It was a really magical thing. I kind of thought, "Oh this is just what a shared studio is like." I've had shared studios since then that have been major disappointments because [with Pizza Island] there was a certain chemistry there. Everybody was doing really amazing work, but everyone's work was really different so it didn't feel competitive. It didn't feel like you were looking over your shoulder and thinking, "How did she get that and I didn't?" Because, well, it's obvious — she's doing that thing and I'm doing this.

It was really inspiring and it was very motivating. It's sad that it only lasted a couple years. Basically none of us could afford to stay in New York anymore and now two of them are in L.A. and Kate is back in Canada and I think Meredith is the only one left in New York. I don't know, if any cartoonists want to start a new studio, I'd be willing to give it a shot — even though it will probably never be Pizza Island. But who knows?

[AUDIENCE QUESTION] I love the style of your work and to me it's very much a documentary illustration. As someone who can also appreciate how drawing someone speaking over six panels can get really repetitive, what would you do to break up that repetition? Did you find yourself working on other projects in between things or would you bounce around from chapter to chapter to take care of that?

Well, that was really hard. That was one of the big challenges of this book because it was a book about the process of journalism. The process of journalism is a lot of sitting around in rooms talking. Someone like Joe Sacco — the process is in there, but it's really about the people's stories, so he can really illustrate what they went through.

I do a little bit of that in the book — like I do some flashbacks — but I didn't do a lot of that because I wanted to keep the focus on the process of journalism. I worried a ton. If I had more than three pages of people sitting and talking and going back from head to head, I started sweating.

Actually, my husband would tell me, "You worry about that too much. It'll be fine." And now I think that it is. It's good to think about that stuff and try to make sure you're not having 20 pages of people taking, but if what they're talking about is interesting, and I hope that it is, then I think that it's all right.

Some cartoonist once said that there should be a drawing of a foot on every page. I don't adhere to that rule completely, but I like the idea that you can vary things a little bit. You can zoom out a little and show the setting the people are sitting in, and kind of give an idea of this space. A lot of times I'll show the details of a room while someone is talking. You can also change camera angles and stuff like that. As far as whether I was working on other things: I was for the first couple years while I was working on this book, but that was more because I didn't want to work on the book because it was hard.

[AUDIENCE QUESTION:] It strikes me that you were there six years ago, and you’re drawing all these drawings and you have to remember what the material environment looked like while you were there. How do you keep that in your mind?

I take a lot of photos. When I go on a trip like this, I'm taking pictures constantly. I do have a sketchbook and that's mostly for taking notes. I'm recording and then if someone's making some weird gesture, I'll write down that he's flailing around madly. But then I'll also be taking a lot of pictures because it's really important to me that the setting looks real.

[Points to the image on the cover of Rolling Blackouts] This is Sulaymaniyah in Iraq. I posted a picture of this cover and a guy I know who's from there recognized it, and that's what I really want. I want people to really feel like this is a specific place.

That means not just cityscapes, but it also means if you're in a restaurant, the certain type of plastic chairs that are there and what the lighting looks like. Anytime when I can't use a camera like a border crossings or something more intimate like interview situations, I would be drawing — like furiously drawing — floor plans and stuff to kind of get that right.

There's a lot that you can hear in a recording when it comes to how someone's mood is. And you're observing them and you're observing body language as it's happening, so then when you listen back to people talking, you can kind of think, "Oh yeah, I remember how they move, I remember she was going like this [makes waving gestures] when she said that."

It is really weird spending five or six years on two months. For my first book too, it was two weeks of time and I spent three years on it. It's this strange extending of time, and you remember moments because you keep forming that memory over and over again. I don't remember what I did in the two months after I got back. I actually have no idea.

Do you find you have a better idea of what details are important when you go into a space as a reporter now or do you still just soak everything up as a sponge and figure out what's important later?

I do, although there's still always the photo that you wish you had taken that you didn't: “I cannot believe I didn't take a picture of the front of that building.” Now I kind of think about that a little bit more when I'm reporting.

I did a comic over the summer about Jill Stein. I followed her around on the campaign trail, and there were still things like threads that I was following that I thought were going to be really important. Then I'm like, "Why did I waste all my time talking to that guy? That didn't make it in at all." It was just actually a distraction. As you get more experience as a journalist, maybe that gets easier, but I think a lot of the deciding what goes in the story happens after you get back and you have a little bit of distance from it.

Over the weekend, Spokane author Sharma Shields and Seattle authors Erik Larson and Jessixa Bagley won big at the Washington State Book Awards. St. Louis poet Carl Phillips, who was born in Washington but has not lived in Washington state for decades, also won. (Here's hoping the Washington Center for the Book at the Seattle Public Library updates the rules to ensure to favor Washington writers in the future.) Moira Macdonald at the Seattle Times has a list of all the winners.

Louis Collins Books celebrates Seattle's long tradition of loving books

Our October Bookstore of the Month, Louis Collins Books, is in a bright blue building at the intersection of 12th and Denny. Collins has been selling books out of this building for decades, and he’s been in the book business for nearly 50 years. Since he does most of his business online, Louis Collins Books is only open for browsing by appointment. I’d urge you to make an appointment: it’s a beautiful space, completely taken over by used and rare books. But unlike the chaos of some used bookstores, everything in Louis Collins Books seems highly organized.

Collins lives in the building, and he invites me back into his kitchen, which is also lined with books, for an interview. “The front of the store is all general art and literature and all that," he explains. “Back here is anthropology, Alaskan history, obscure archaeology texts, ethnomusicology, that kind of thing.”

Collins buys most of his books in the form of personal libraries — and many of the libraries he’s buying these days, he notes, have been bought in pieces over the years at Louis Collins Books. He points over at three shelves in the corner of the kitchen. “I bought a wonderful collection from a woman who specialized in the folk songs of southeast Asia,” Collins says. The collection used to take up a couple whole bookshelves in the kitchen, but after he made the books available to his online customers, it’s now down to a few shelves.

Walking around Louis Collins Books, you’ll see a number of books you simply can’t find anywhere else. If you were to survey random people on the street, most of them would likely say that every book ever published exists online. That’s not anywhere close to true. Collins estimates that when he enters his collection into online databases, nearly half of his books aren’t available at any other online retailers. Finding those one-of-a-kind titles seems to be a source of great pride for him.

I ask Collins if he likes shopping at any local bookstores. Unequivocally, the answer is yes. “This is a great book town, and it’s always had great bookstores here,” Collins says. When he was a rare and antiquarian bookseller in San Francsisco, he used to make book-buying trips to Seattle to replenish his supply. “There have always been very good customers here, too,” he says.

But is it hard to find rare books in a part of the world that’s had books in it for less than two centuries? Collins says Seattle has always been home to impressive book collectors, and when you look back to shipping manifests from the city’s earliest days, you’ll find large shipments of books from England arriving in the city on a regular basis. This is a city that has always embraced book-lovers. In his little blue shop on Capitol Hill, Collins is continuing a long tradition of Seattle-based sellers of rare and unique books.

The Sunday Post for October 9, 2016

Dark Fruit: A Cultural and Personal History of the Plum

A wonderful piece by Anca Szilágyi on the cultural history and meaning of plums.

In the beginning, there was găluşti cu prune — plum dumplings. My mother’s mother, in August, plum season, steaming up the kitchen, boiling them in a big pot. These were the days before summer camp, before air conditioning. An electrical storm was coming. She warned me not to turn on the television or switch on the light. I thought that if I even touched the window, there would be a blue electric shock. The dumplings that survived the boiling she fried in sugar and breadcrumbs. The disintegrated balls — white lumps of potato dough and misshapen chunks of plums — she set aside for me. The whole ones — perfect, round, sparkling — were for my parents.

A plum dumpling is a perfect universe: the first encounter with granular, sugary crumbs; the dense, substantial wrapping that you sink your teeth into; and the juicy, sweet, and sometimes tart Italian prune plum center that veers toward sublime.

The Novelist Disguised As a Housewife

Ruth Franklin argues that Shirley Jackson was successful because of her children, not despite them.

In June 1948, Shirley Jackson’s story “The Lottery” — a dark fable about a ritual stoning conducted in an apparently ordinary village — roiled the readers of The New Yorker, generating more mail than the magazine had ever before received in response to a work of fiction. A few months later, Jackson arrived at the hospital to deliver her third child. The clerk asked for her occupation. “Writer,” she replied. “I’ll just put down housewife,” came the response.

What makes a children's book good?

Adam Gidwitz on the quality of children's books, and what adults and kids think makes them "good".

The conundrum of the “good” children’s book is best embodied by the apparently immortal—or maybe just undead—series “Goosebumps,” by R. L. Stine. “Goosebumps” is a series of horror novellas, the kid’s-lit equivalent of B-horror movies. It’s also one of the most successful franchises in the business, selling over three hundred and fifty million copies worldwide—which is a ludicrous, almost obscene, number. And here’s a secret from the depths of the publishing industry: neither marketing nor publicity nor movie tie-ins can move three hundred and fifty million copies. The only way to sell that many copies is if millions of kids actually and truly want to read the books. The conclusion is obvious: “Goosebumps” books are good, right?

Lynd Ward and the Wordless Novel

Rich Rennicks has an appreciation of artist Lynd Ward in the New Antiquarian.

The so-called graphic novel — which may be no more than a successful rebranding of comics — has become a very popular genre, with its own bestseller list in the New York Times, and growing shelfspace in new book stores. In light of this new-found prominence and respectability, it's interesting to look back at the precursors to the graphic novel, the stages the idea of the illustrated novel-length story went through before settling into the form we current know. One of these stages was the wordless novel, in particular the work of American Lynd Ward, who was both an influential illustrator of children’s books (he won a Caldecott Award) and a pioneer of the wordless novel.

Modern Filipino Children's Stories: Sari-Sari Storybooks - Kickstarter Fund Project #40

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

Modern Filipino Children's Stories: Sari-Sari Storybooks. We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer.

Who is the Creator?

What do they have to say about the project?

These gorgeously illustrated picture books bring Filipino stories to the world. Printed + media-rich digital books.

What caught your eye?

This project seeks to publish books in more Filipino languages than just English or Tagalog. As she says in the video, there are 181 languages in a country the size of Florida (update: Christina contacted us to say Arizona is a better match than Florida, and she's correcting the video to say so), and by creating books in some of those other languages, it both reinforces the local cultures, while also sharing them with the world — since each book will also be translated into English.

Why should I back it?

Besides the altruistic drive of the creation, the books look amazing. I remember, as a kid, reaching out into other cultures through their stories, learning about the experiences of children far different than my white suburban childhood. But just wanting to expand a child's horizon isn't enough, it has to be done well. From the looks of it, these books are well written, nicely illustrated, and well presented. It's a great concept presented well.

How's the project doing?

71% funded with 24 days to go. Wouldn't it be great to see them hit a total home run?

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 40

- Funds pledged: $800

- Funds collected: $760

- Unsuccessful pledges: 2

- Fund balance: $240

I'm thrilled to hear that the great Spokane alternative weekly the Inlander — which, full disclosure, publishes my writing sometimes — is planning a poetry issue. And if you live in eastern Washington, they want you to send your poetry to them sometime before November 20th. They will publish roughly a dozen poems, with each poet receiving $40 for their work. Many thanks to the Inlander for supporting local poetry; I can't wait to read this issue.

(Thanks to SRoB tipper Hannah for the tip.)

The Help Desk: I'll bet his place smells like tannis root

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

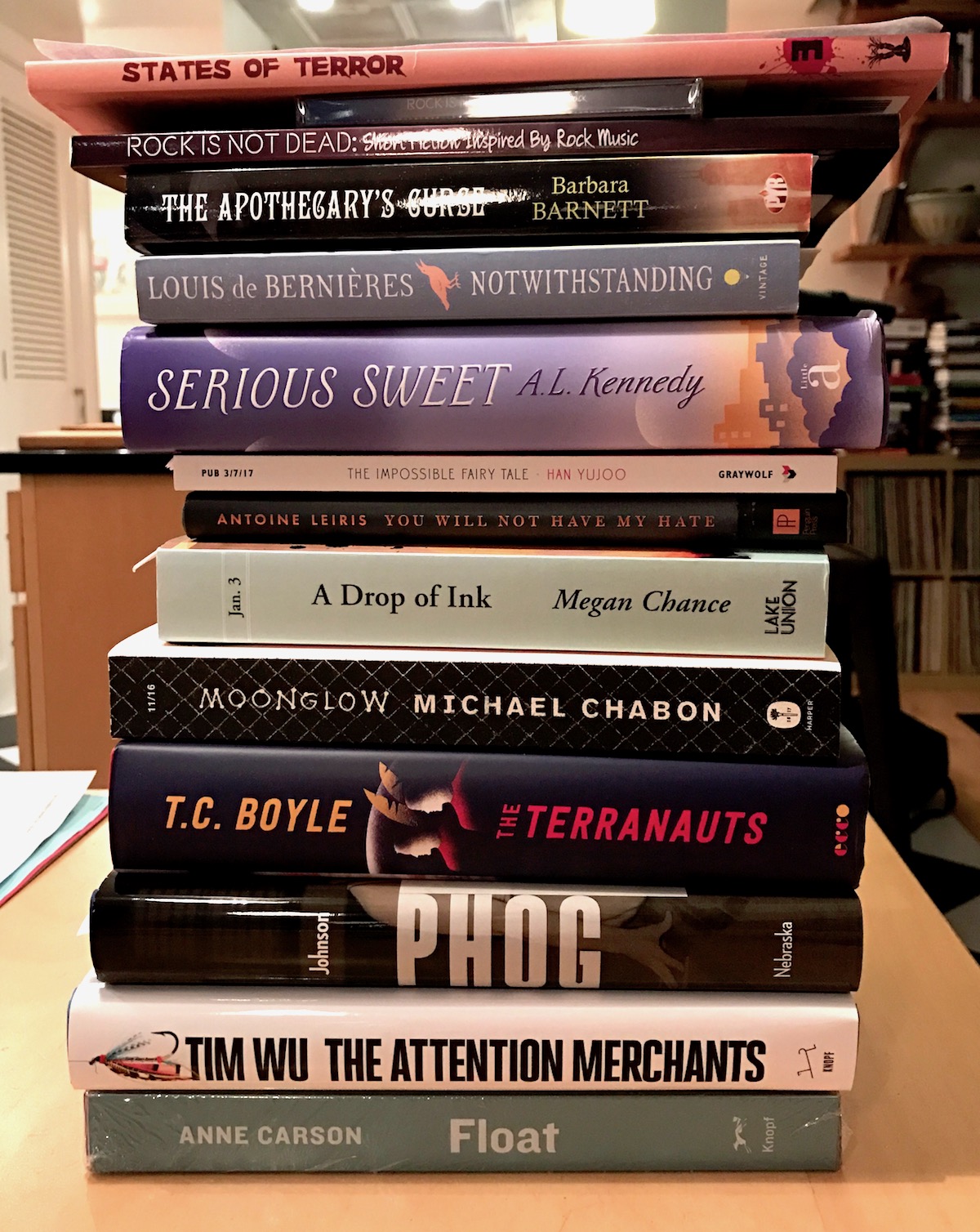

I have a dumb problem. I can't seem to stop buying books. Shelves and shelves of once-hot titles and cool reissues and cult classics and sometimes just out-and-out garbage. I keep a running list on Amazon. I have a section of my bookshelf dedicated to stuff from library sales. (Fifty cents a book! How am I supposed to resist that?) I recently took three giant boxes of musty 70s paperbacks off my mom's hands just because.

However, that's not really the problem. The problem is, I never seem to read any of them. I spend so much time on Twitter, on the internet, binge-watching TV on Netflix, that I never get around to just sitting down and reading. I have plenty of space for all these books, but one day I'm going to run out. I don't want to part with any of these books, either; that feels like giving up, and rendering it all pointless.

Cienna, should I just buckle down and accept that I'm not a reader anymore and get rid of all these books? Should I fling off these electronic distractions like some kind of ascetic monk and focus on print? Should I just go into therapy?

By the way, would you like a funny-smelling copy of "Rosemary's Baby"? I have three.

James, Delridge

Dear James,

You're not a reader. Your hobby is hoarding, not reading – and as far as hoarding goes, you're in good shape. Books are generally a compact and nonpsychotic option, unlike antique corpses dressed as little girls.

Fortunately, anyone can become a reader at any point. All you have to do is pick up a book, open it and read it. You don't have to read it very fast or very well, or limit yourself to one at a time. You don't have to finish a book that doesn't engage you. Books, much like antique corpses dressed as little girls, aren't very judgy.

I understand how distracting the internet can be. I just spent 90 minutes googling "antique corpses dressed as little girls." Like you, I've also spent years of my life collecting books more than reading them. But at a certain point, I made a choice to start living like the person I wanted to be, and that included moving into the Trump Tower of basements, launching my own business that combines pantomime and improve into a dynamic new public art form I call "pantoproving," and reading the piles of books that I've lovingly collected for years. Like anything worth doing in life, reading takes stamina and dedication, but the satisfaction and awe I experience when immersed in a world invented by another human being is unmeasurable. It's as if the art of lying finds its altruistic higher calling through novels.

Please send my smelly copy of Rosemary's Baby c/o Seattle Review of Books, 7 Mercer Street, Seattle WA, 98109. As a tribute to you, I will dedicate my next pantoprov session to its content. (If you see a woman silently birthing a demon in a Target bathroom on Saturday, don't be afraid to say "hello!")

Kisses, Cienna

Yesterday, Fantagraphics Books published a page called "The Truth About Pepe." It's an attempt to reclaim cartoonist Matt Furie's character Pepe the frog from the racist so-called "alt-right" Trump supporters who have adopted the cartoon frog as an in-joke, a meme, and as a cultural signifier. Pepe has since been identified as a hate symbol. Fantagraphics says:

Having your creation appropriated without consent is never something an artist wants to suffer, but having it done in the service of such repellent hatred — and thereby dragging your name into the conversation, as well — makes it considerably more troubling.

Fantagraphics Books wants to state for the record that the one, true Pepe the frog, as created by the human being and artist Matt Furie, is a peaceful cartoon amphibian who represents love, acceptance, and fun. (And getting stoned.) Both creator and creation reject the nihilism fueling Pepe’s alt-right appropriators, and all of us at Fantagraphics encourage you to help us reclaim Pepe as a symbol of positivity and togetherness, and to stand by Matt Furie.

The optimist in me would like to encourage Fantagraphics' attempt to reclaim Pepe, but the pessimist in me believes that this kind of appropriation is really, really difficult, if not impossible, to undo. Generally, when it comes to symbols, you can only add meanings, not subtract them. And when a detested subgroup like neo-Nazis Trump supporters embrace a symbol, that symbol effectively becomes toxic.

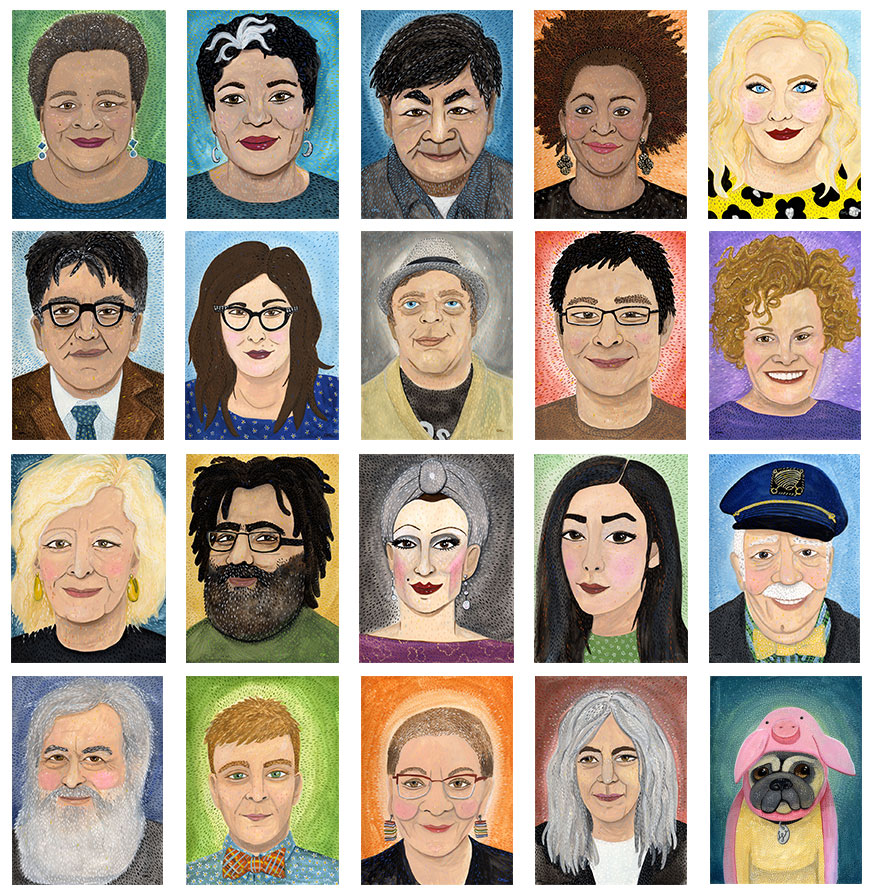

Portrait Gallery: Luvvie Ajayi

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Tuesday October 11th: I’m Judging You Reading

Luvvie Ajayi is a Nigerian-American author who writes essays about politics, feminism, race, pop culture, and the wrongness and rightness of people on the internet. As part of a celebration of her new book I’m Judging You: The Do-Better Manual, Alayi will appear in conversation with Lindy West.

Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Get painted by Christine!

Christine is taking on a limited amount of commissioned portraits, in her Seattle Review of Books style, in advance of the holidays. If you want a portrait of a friend, loved one, pet, or even yourself (immortalize your bossest selfie!) for your own wall, or as the most thoughtful gift you can possibly imagine, then please do reach out. There's more information on her website.

Traveled the world and the seven seas

Published October 06, 2016, at 11:48am

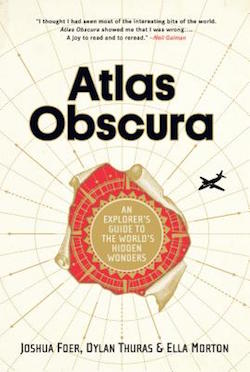

Atlas Obscura's new book is a compulsively readable travel guide to some of the world's strangest locations, from Galileo's Middle Finger to a pair of Necropants.

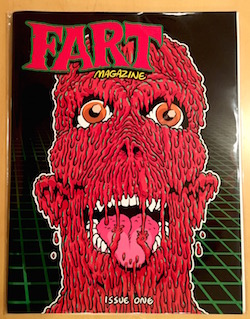

Thursday Comics Hangover: [Fart noise]

The first of what is sure to be many Seattle-area periodicals trying to fill the void left by shuttered comics anthology Intruder has arrived, accompanied by a fart noise. The first issue of Fart Magazine, edited by Mark Allender, includes contributions from Intruder contributors like Marc Palm and Seth Goodkind.

Unlike Intruder, Fart isn’t an all-comics joint; magazine-like, it features text pieces (essays from contributors like Emmett Montgomery and Elicia Sanchez) and a celebrity interview (with comedian Brian Posehn). Also, unlike Intruder, Fart has a central theme: most of the pieces have to do with farts, or poo jokes, or both. Truth in advertising lives! (Though Sanchez contributes an essay on queefs, which may or may not fit the criteria, depending on how you feel about it. Sanchez herself chafes when the two are compared; it’s kind of the point of the essay.)

Intruder thrived in part because of its unique specifications: every artist could fill a full-sized tabloid newspaper page any way they wished. The artists in Fart — the fartists? — are not necessarily limited to a single page, and a bit of restraint might have been useful; the pacing of the issue is a little strange. At four pages, a strip about orc roommates feels too long, for instance, while another single-page gag strip involving potty humor and suicide is very funny but might have benefitted from more space.

But the grade-schooler in me is in love with the idea of a magazine called Fart, and the exuberance of the issue, the willingness to commit to the joke, is truly impressive. The magazine could use a stronger editorial hand. Palm had a knack of getting the most —the absolute best work — out of his contributors, but Fart has a couple of subpar strips that could’ve used some more time, some more talent, or both.

But so much depends on the future of Fart. You couldn’t tell just from the first issue of Intruder that something neat was happening; only the accrual of more issues made it into a legend. If we see more issues of Fart that continue to hew to the gassy theme while upping the quality of the contributions a little bit, this could be something special. Not that there’s anything wrong with a funny one-off; it’s just there’s a promise to Fart that would be a shame to waste. Twenty issues of a magazine about farts and fart-related topics? That’s the kind of commitment that turns heads.

Why can't Dick Lit authors write normal books like everyone else?

If you're not aware of the @manwhohasitall Twitter feed, I'd encourage you to follow it. It's a simple premise — reversing the gender on common ignorant sexist statements — that pays off in so many enjoyable ways. Some examples:

"Men shouldn't run for president because of their hormones," says male CEO, Paul, 60. Interesting that this comment comes from a man.

"I don't mind being called a gentleman driver because it's true, I'm a gentleman and I'm a driver." Mark, gentleman driver.

'Male politician' is NOT an offensive term. It is simply a way to differentiate them from normal politicians. End of story.

You get the idea. The Man Who Has It All Facebook page a few days ago shared an image of a woman with the words "'I don't like men's writing.' — Amy, literary critic" below it. And then the commenters got in on the act, and it's a beautiful thing to behold.

Oh come on, it's good for the boys to have some Dick Lit to read after they've cooked dinner and put the kids to bed.

They only ever write about the same things, with such narrow life experiences. I can't relate to any of it, and none of it is really that important, is it. I studied a man-writer at school and couldn't get into it, and that put me off the rest.

It can be quite interesting, but it's always going to be a sub-genre. It just doesn't cover the broader issues and it's not relevant to most of society. It's nice that they have their own little awards though.

I don't mind men's writing, but only if they don't bring their agenda into it and only talk about men's issues!

I feel a bit bad now, because I just looked at my bookshelf and almost all the books are by normal authors. I should really get a couple of books by male authors to even it out.

It's not that I prefer women writers per se, it's just that if you look through history, at the classics, it's mostly women. If men want to be among the greats, then just do it instead of whining! Pick up your pen and write that classic. I'll wait.

It is an unbelievably refreshing thread that unspools so many of the condescending things men say about women in literature. I urge you to check it out. You'll never think about Dick Lit authors, with their guns and cars and egos, in quite the same way again.

This ABC News story certainly isn't terrifying or anything.

The executive director of the Kansas City library system says he is "outraged" that prosecutors continue to pursue charges against a man who was arrested after asking pointed questions during a library discussion about the Middle East peace process and an employee who tried to intervene.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from October 5th - October 11th

Wednesday October 5th: Rolling Blackouts Reading

With her ear for powerful, personal stories, new-to-Seattle cartoonist Sarah Glidden is the finest journalist to hit comics since Joe Sacco first put pen to paper. Her latest book, Rolling Blackouts, is a powerful piece of reportage that investigates what the Iraq War was like for ordinary people in the Middle East. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Alternate Wednesday October 5th: Contagious Exchanges

At the Seattle Review of Books, we take conflicts of interest seriously. And so because I’m hosting the post-reading Q&A with Sarah Glidden at Elliott Bay Book Company, I also want to provide you with another option for a reading. And this is an important one: Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s new series featuring “Queer Writers in Conversation,” Contagious Exchanges, kicks off with incredible local author Rebecca Brown and artist C. Davida Ingram. Hugo House, 1021 Columbia St., 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Thursday October 6th: Pongo Housewarming

Pongo Teen Writing is an incredible local program in which volunteers teach young people in juvenile detention centers, psychiatric wards, and homeless shelters around the region how to express themselves through poetry. Tonight, Pongo settles into its new home in Washington Hall with a reading from amateur and professional writers. Washington Hall, 153 14th Ave, http://pongoteenwriting.org. Free. All ages. 6:30 p.m.Friday October 7th: Celebrating Filipino-American Elders

Members of Seattle’s up-and-coming Filipino-American writing community, including Maria Batayola, Robert Flor, Donna Miscolta, Michelle Peñaloza, Jen Soriano and Maritess Zurbano, will read for and with older Filipino-Americans on Beacon Hill in a reading, open mic, and karaoke party. (Here’s a little-known fact: writers, as a rule, are fantastic at karaoke.) International Drop-In Center, 7301 Beacon Ave. S., http://www.idicseniorcenter.org. Free. All ages. 1:30 p.m.Saturday October 8th: Atlas Obscura Presents: a Subterranean Soiree

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Underground, 614 1st Ave., http://atlasobscura.com, $60, 21+, 9 pm.Sunday October 9th: Dog Man Reading

A whole generation of kids has grown up in the thrall of author Dav Pilkey’s baby superhero, Captain Underpants. Today, he debuts his new comic for young readers: Dog Man, another crime fighter — this one with the head of a dog and the body of a man. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 2 p.m.Monday October 10th: Last Look Reading

Brilliant cartoonist Charles Burns was born and raised here in Seattle, and his masterpiece, Black Hole, is a book that practically smells like the Pacific Northwest. Burns’s latest book, Last Look, collects his three most recent titles into one volume. It’s a riff on Tintin, teen angst, and the soul-twisting power of rock music. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $10. All ages. 7:30 p.m.Tuesday October 11th: I’m Judging You Reading

Luvvie Ajayi is a Nigerian-American author who writes essays about politics, feminism, race, pop culture, and the wrongness and rightness of people on the internet. As part of a celebration of her new book I’m Judging You: The Do-Better Manual, Alayi will appear in conversation with Lindy West. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Literary Event of the Week: Atlas Obscura Presents a Subterranean Soiree

So far as travel resources go, the website Atlas Obscura isn’t stodgy like Frommer’s, and it’s not overly obsessed with shopping like Lonely Planet guides. Instead, it’s interested in bizarre destinations and singular geographical points of interest: on their site right now, you’ll find offers to visit Icelandic sorcerers who perform “evil-ridding” ceremonies and a map marking the homes of heroes of children’s literature including Beverly Cleary’s Portland-based Ramona Quimby.

Pai is a perfect fit for Atlas Obscura’s mission, which she describes as a charge “to inspire a sense of curiosity and wonder.” She’s always been intensely interested in geography, from her collection Aux Arcs, which was all about her ill-fated move to the Ozarks, to last year’s project where she used sunlight and special stickers to "grow" the words of a poem on the skins of apples growing in a public orchard in Carkeek Park. In her new role as the head of the Seattle Obscura Society, she’s charged with “planning events in obscure places that offer elite or exclusive access” to interested Seattleites.

The first big party Pai is assembling will serve as both a kickoff for the Seattle chapter of the organization and a launch party for the Atlas Obscura book. The “Subterranean Soiree” on the evening of October 8th, she explains, “will be a tour of the Seattle Underground, with access to a part of the Underground that many people do not often get to see.” Under the streets of Pioneer Square, partiers will enjoy food, drinks, and live music from Greg Ruby and his Prohibition-era jazz quintet.

Pai says she’s “drawn to and excited by the idea of producing uncommon experiences that are not limited or constrained by the arts.” Each event exists somewhere in the common spaces of a Venn diagram of music, food, visual art, history, and the written word. She’s packed the next month or so with experiences that could only take place in the Seattle area: a tour of Robert Irwin’s UW campus art installation, a tea ceremony including a meal and guided meditation at Laurelhurst’s underappreciated East-West Chanoyu Center, a trip to a letterpress studio featuring a printing demonstration from artist Myrna Keliher, a Halloween Eve walking tour of Lake View Cemetery, a visit to a studio of fashion designer Malia Peoples, and an interactive lecture on the visual art of slime mold.

Pai believes Atlas Obscura and Seattle are a perfect fit. She looks forward to assembling a portfolio of events predicated on “the idea that we are all producers or makers with a capacity for the creation of wonder.” Interested parties can sign up for the Seattle mailing list or join the Facebook group at atlasobscura.com.

Seattle Underground, 614 1st Ave., atlasobscura.com, $60-90, 21+, 9 p.m.