The Sunday Post for August 14, 2016

The world’s first website went online 25 years ago

25 years and a week ago, Sir Tim Berners-Lee created a basic text page with some hyperlinks. It was a simple description of his “WorldWideWeb (W3)" project. Cara McGoogan describes how he imagined the possibility of sharing information across the world. Here we are a quarter of a century later with over a billion websites online, using Google as a verb, and lamenting how many email accounts we have. Tim Berners-Lee might not ring a bell for many, but he garnered significant attention after appearing in the opening ceremony for the London 2012 Olympics.

Berners-Lee wanted the World Wide Web to be a place where people could share information across the world through documents and links navigated with a simple search function.

The first step to making that a reality occurred on August 6, 1991, and was hailed with little fanfare when Berners Lee launched the first web page from his NeXT computer at CERN's headquarters in Geneva.

When an Island’s Lone Caretaker Leaves

An intriguing man-in-nature vs. the government story: Mauro Morandi has lived alone on Budelli — a small Mediterranean island — for a quarter of a century, but because of legal conflicts, Italy is considering his eviction. Livia Albeck-Ripka notes the symbolism of the situation. It is a tale conveying the importance of environmental protection and of the respect that should exist in humans’ relationship with nature.

In 1991, Italy’s ministry of environment declared Budelli’s pink beach a place of “high natural value.” By 1999, the beach was closed to visitors entirely. Tourists could still wander along a track behind the Spiaggia Rosa, but were no longer permitted to swim in the ocean or touch the sand. Morandi watched over the beach’s fading coastline and took the opportunity to teach visitors—those interested, at least—about its ecosystem. “I welcome tourists who want to know the fool who lives in solitude,” he says. “I speak to them of beauty, love for nature, the peculiarity of the Spiaggia Rosa.” Once, he got into a fistfight with picnickers who came to Budelli armed with deckchairs and inflatable toys—garish metaphors for humanity’s failure to respect the natural world, in his view. “We must get on our knees in front of this wonder of nature,” he sighs. “We must safeguard it.”

I'm an OB-GYN treating women with Zika: This is what it’s like

As Zika cases increase and people demand for more research, the new disease and its international spreading keeps racking up fear and bewilderment. Christine Curry and others in the medical field have had to develop ways to confirm diagnoses, inform infected mothers of the risks, and plan for a baby’s birth if the case calls for it.

As a medical student, I remember reading books about the early days of the HIV epidemic and wondering what it was like for doctors to take care of patients who had a new, unknown disease. It seemed to me like it would be frightening for both patients and doctors alike. I didn’t expect that early in my career as an OB-GYN, I would be caught in the middle of another new disease outbreak – Zika.

Meet the California Couple Who Uses More Water Than Every Home in Los Angeles Combined

Josh Harkinson details how Lynda and Stewart Resnick came to own America’s second-largest produce company, and they seem like terrible people: they use an exorbitant amount of California’s water, the state’s most precious (and scarce) resource. However, they donate millions to charity and invest more millions into their community, Lost Hills, funding assorted things like sidewalks and health clinics. Despite being health- and philanthropy-oriented, skeptics still call them out on being “the top 1 percent wrapped in a green veneer ... of social justice.”

The Resnicks have amassed this empire by following a simple agricultural precept: Crops need water. Having shrewdly maneuvered the backroom politics of California’s byzantine water rules, they are now thought to consume more of the state’s water than any other family, farm, or company. They control more of it in some years than what’s used by the residents of Los Angeles and the entire San Francisco Bay Area combined.

Why Every President Sucked: Hardcover Book - Kickstarter Fund Project #32

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

Why Every President Sucked: Hardcover Book.. We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer

Who is the Creator?

What do they have to say about the project?

Why Every President Sucked uncovers how each and every former president has failed to live up to our divine expectations.

What caught your eye?

If there's one thing you learn after voting for a few presidents (assuming you're lucky enough to see the one you vote for get elected), it is this: that person you believed in and campaigned for, who said such perfect, prescient things, that person, when in office, will disappoint you.

It's one reason many of my friends had little truck with Bernie Sanders, for example: that bright light leading you through the darkness of political chaos, once in office, will do something you think stupid, shortsighted, or otherwise frustrating. The more messianic his followers, the more skeptical they become, and the farther the fall from grace when in office.

More than that, it's okay to be disappointed. Obama disappointed on many fronts, but that doesn't mean his presidency wasn't successful. It means he's a human living in political times that is trying to work within the system to do something grand, and sometimes failing.

So, let's say it clear: a Donald Trump presidency would be a disaster, if he acts just like he says he will. But a Clinton presidency will suck, too, for a lot of reasons. People who think they get to "vote for someone, not against someone" are not recognizing a fundamental truth of America: you are electing a flawed human, who will do bad things and good things. It's just in this case, the bad things potential is off the scale on one side.

Why should I back it?

To help us all remember: no president is perfect. Even George W. Bush made some decisions that benefitted the country, in any objective view. Were they enough to balance the bad he did? History will decide. Back this to help us remember, in four or eight years when we're going through this again, that every president did something stupid. Even the great ones. In fact, especially the great ones, who managed to make big things happen despite their mistakes.

How's the project doing?

They've only got about $500 of their $10,000 goal. Maybe they should consider showing a few actual samples...? In any case, they need the help.

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 32

- Funds pledged: $640

- Funds collected: $540

- Unsuccessful pledges: 1

- Fund balance: $400

What Donald Trump's favorite poem tells us about Donald Trump

Near the beginning of a speech at the end of July, Donald Trump asked a hall full of people at the Air & Space Museum in Denver: “Now, you know, should we read ‘The Snake?’” The room erupted with cheers. Trump, playing coy, asked again: “Should we? Does anyone know ‘The Snake?’” This was met with more cheers. Ever shameless, Trump asked again, “should we do it?” Still more cheers. Trump asked a couple more times, to more cheers, if anyone knows “The Snake.” The routine was like a one-hit wonder rock musician at a festival, playing the first strains of the only song anyone wants to hear before stopping and playing something else: a wet, sloppy tease to keep the audience’s attention.

“Let me put it differently,” Trump asked, “who has not heard it?” Still more cheers. “A lot of people. OK. Before we do that — we will do it — I have to tell you…” And then Donald Trump proceeded to not read “The Snake.” In fact, he engaged in an hour-long meandering one-sided conversation about everything on his mind, from Hillary Clinton’s convention speech to how popular Donald Trump is to how much Donald Trump loves John Elway.

Finally, about an hour or so later, Trump abruptly dammed up his stream of consciousness and offered a preamble:

People like this — people like it. This was actually a song written by Al Wilson quite a while ago. This really pertains to what we talk about what we talk about illegal immigration. Let me do this. I read it a couple of times and people love it. It is called "The Snake." this pertains to people coming across the border and people coming in from Syria.

And then, Donald Trump read the lyrics to a song without accompanying music. Which is to say, Donald Trump read a poem. To a rapt crowd of thousands, Donald Trump read the poem that has become his signature campaign move, the coup de grace for most of his speeches. That the poem is based on one of Aesop’s fables is even more staggering, giving the whole experience the air of a children’s storytime, or a bedtime story from a particularly boisterous uncle.

“The Snake” begins with a “tender-hearted woman” who finds “a poor half-frozen snake.” She sees that “his pretty colored skin had been all frosted with the dew.” She decides to take him in, which introduces the song’s chorus:

"Take me in tender woman

Take me in, for heaven's sake

Take me in, tender woman, " sighed the snake

The woman does, offering the snake a “comforter of silk” and “some honey and some milk.” Later that day, she finds that the snake has recovered. She happily embraces the snake but, inevitably, “instead of saying thanks,” the snake gives the woman “a vicious bite.”

"I saved you, " cried the woman

"And you've bitten me, but why?

You know your bite is poisonous and now I'm going to die"

"Oh shut up, silly woman, " said the reptile with a grin

"You knew damn well I was a snake before you took me in!”

The crowd, it must be said, ate it up. Trump read the poem with all the gusto of a children’s theater performer, slowing down his performance to amp up the suspense, bellowing the woman’s lines with all the aggrieved hurt he could muster. And the crowd went nuts over the poem, stomping and cheering and just generally yelling their damn heads off. It provided an emotional climax for the show — Trump left the stage soon after finishing “The Snake” — and it acted as a sort of lens through which the evening’s hatred and xenophobia and racism could be focused and made clear. Those howls of approval? That’s the sound of thousands of hateful worldviews being confirmed all at once by a single work of art.

As with any story about Donald Trump, we have to set aside a moment here to separate what he says from the truth. “The Snake” was released by Al Wilson in 1968, but Al Wilson did not write the song. It was written by a Chicago singer and activist (and one-time Communist Party member) named Oscar Brown, Jr. Brown passed away over a decade ago, but his family has repeatedly asked Trump to stop using the lyrics in his speeches. Lara Weber at the Chicago Tribune writes:

"We don't want him using these lyrics," said Brown's daughter, Maggie Brown, also a distinguished singer. "If Dad were alive, he would've ripped (Trump) with a great poem in rebuttal. Not only a poem and a song, but an essay and everything else."

This is surely a level of hell: you spend your entire life fighting for social and racial justice and then the most openly racist presidential candidate in several generations treats the lyrics of one of your songs like the “Free Bird” encore at a Skynyrd show. The fact that Trump gets the authorship of the lyrics wrong every time is simply one last thumb in the eye after a horrifying act of artistic appropriation.

Recently, Tony Schwartz, the ghostwriter who worked on Donald Trump’s book The Art of the Deal, pointed out that the key to understanding Trump is this: when he tosses around insults, he is really talking about himself. With this insight in mind, you can see all Trump’s insecurities swirl to the surface in his attacks: he’s called Hillary Clinton “a lose [sic] cannon with extraordinarily bad judgement [sic] & insticts [sic],” he’s labeled Elizabeth Warren a “racist,” said President Obama “doesn’t have a clue,” and he loves to call the press “dishonest.” It’s like he’s performing advanced psychotherapy on himself by projecting his self-loathing onto the world.

And so with that discovery in mind, consider what Trump might find so compelling about “The Snake.” Audiences seem to interpret the poem as a charge against kindness. Trump supporters like to say that we can no longer afford to accept immigrants because our generosity has been taken advantage of again and again. The implication is that we need to get our house in order before we open our doors again. But that’s a misreading of “The Snake.” Instead, “The Snake” is about believing against all evidence to the contrary that someone’s nature will change in different circumstances.

For the last few months, Republican leaders have tried to assure the electorate that Trump would pivot during the election, that he would start calming down and presenting as a more reasonable candidate when we got closer to the general election. Trump himself has said that he would act presidential if he won the election. We have repeatedly been told — by Trump’s family at the Republican National Convention, by Trump himself, by Trump’s running mate — that we are not seeing the real Donald Trump.

But what Trump is telling us with “The Snake” is that he is the snake in that story, and that he will never stop spreading his poison. Trump’s whole pitch is that he’s been an asshole his entire life, and that he’s willing to be the asshole on our behalf for a change. He’s proud of his bankruptcies, his tax-dodging, his dishonorable business practices. Many of his followers argue that he’s just the kind of monster we need to even the playing field with international competitors. But in his speeches, Trump himself keeps urging us to believe the evidence before our eyes: we know damn well he is a snake, so why would we take him in?

The Help Desk: Are adult coloring books a fad?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Recently, when I was watching the so-so Pride and Prejudice and Zombies movie, I was reminded of that fad when authors were inserting genre elements into works of classic fiction, like Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters. Even at the time, I thought that whole thing was pretty silly and I could tell it wasn’t going to age well.

And now, I can tell that the whole adult coloring book thing is another fad and it’s going to look pretty ridiculous five or seven years from now. Why are we such huge suckers for this sort of thing? Would books be in better shape if authors didn’t chase after every dumb fad that came along? Or is it just human nature?

Faye, Queen Anne

Dear Faye,

You are correct – fads are one of the weirder aspects of human nature, a pop-culture shorthand of creating collective memories that root us in a specific time, space, and sentiment. Unlike cultural movements, fads have weak historical context and add nothing relevant to a group's cultural identity. Still, some fads are not terrible, like ice bucketing yourself or being seen in public with a copy of Lean In (some might argue that Lean In is a culturally important part of a larger feminist movement, I would argue that it sought to capitalize on the movement while offering nothing more than the same milquetoast platitudes and upbeat generalizations found in all self-help books).

Then again, sometimes fads are the physical manifestation of a cringe, otherwise known as “white dreadlocks syndrome.” I would put adult coloring books in that category, along with naming children after kitchen nouns.

Writers can employ fads deftly and to their advantage – take the popularity of Ready Player One. That book is steeped in nostalgic 80s pop-culture references, which make its children-of-the-80s audience feel both clever and sentimental for picking up on its retro references without the author having to do much, if any, leg work.

I hope to become one of those writers. I trust I can count on you, Faye, to support my latest literary endeavor, which might generally be described as “erotic Charlotte's Web fanfic.” I'm hoping to seductively inspire generations of children with a new take on an old farm-to-table classic, guest-starring more spider lap dances than most kids have the capacity to count. Stay tuned to the Seattle Review of Books for a short excerpt!

Kisses,

Cienna

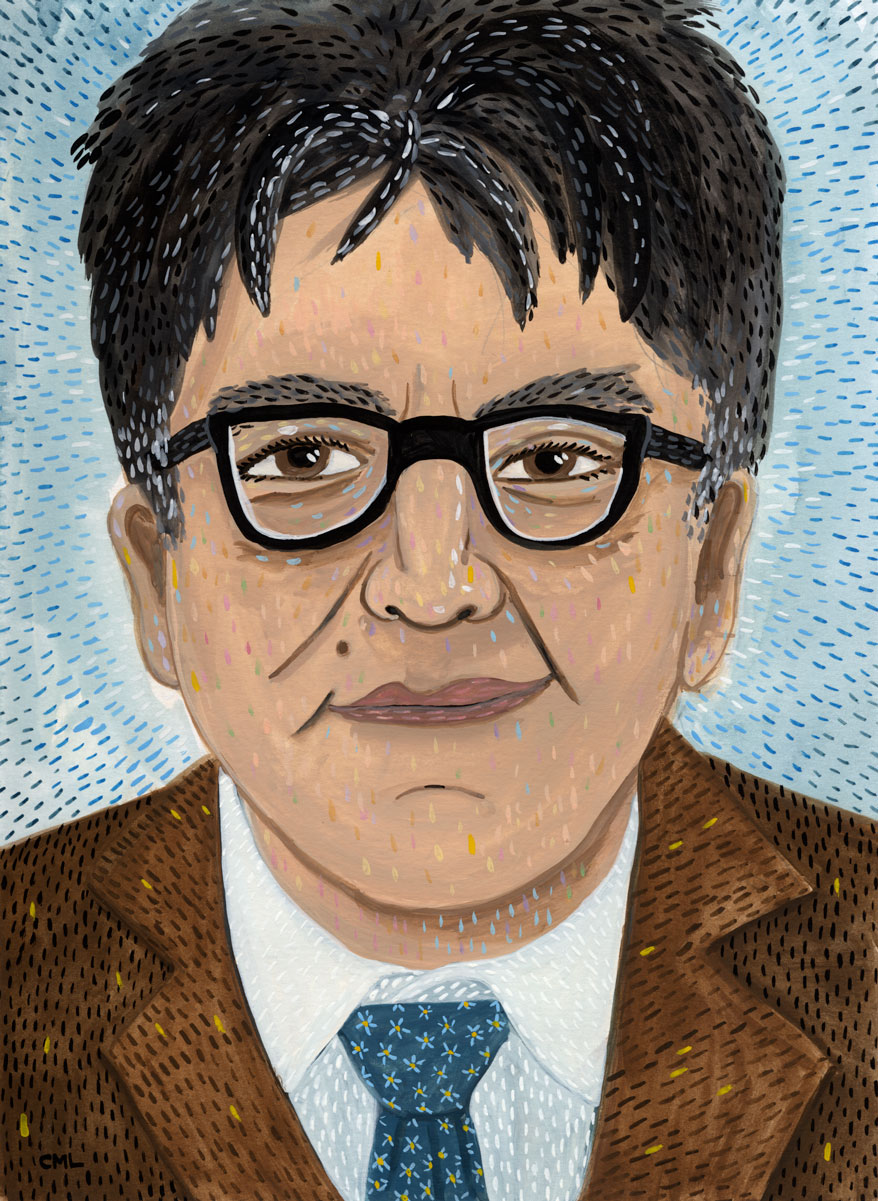

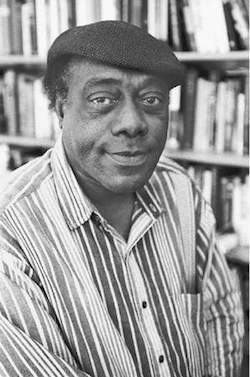

Portrait Gallery - Sherman Alexie

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

This week is a rerun of Seattle's beloved Sherman Alexie, who's reading this Sunday at Queen Anne Book Company. He'll be presenting his children's book, Thunder Boy Jr. And don't forget about Alexie's appearance at Bumbershoot at a Seattle Review of Books event in just a few weeks!

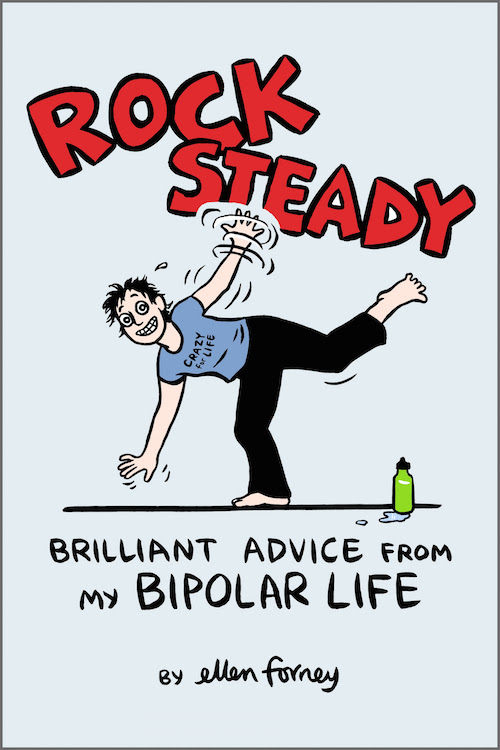

Fantagraphics announces new Ellen Forney book

What a terrific email to get on a Thursday afternoon: Fantagraphics Books just announced that they're publishing the next book from Seattle cartoonist Ellen Forney. With her debut full-length graphic novel, Marbles, Forney eloquently shared her story as a bipolar artist. Rock Steady: Brilliant Advice From My Bipolar Life will offer autobiographical anecdotes and observations about "how to overcome the hassle of meds, recognize red flags, and other tools from her own experience of 14 years of stability - all in comics form."

Here's the cover:

It's wonderful to see Forney publishing with Fantagraphics again — Seattle publishers should represent Seattle authors whenever they can — and it's awesome to see Forney continue to take on the stigma surrounding mental health topics.

Now, the bad news: Rock Steady is not coming out until 2018. Comics take time to make, folks.

Yes. God, yes.

Question-based headlines prompt a more negative response from readers as well as a more negative expectation of the story that follows compared to traditional news headlines, showed a report published on 9 August by the Engaging News Project.

Remember the rule of thumb: if the headline is a question, the answer is almost always "no." Headline writing has, in recent years, transformed from an art form — a good headline is a piece of writing that communicates with the piece as well as promoting the piece — into an impossibly dry chunk of information.

Why did it change? Well, social media. Headlines have to be designed to grab people on Facebook, which means you can't write a headline with the assumption that someone will read the attached story. (Ask anyone who works in social media and you'll learn that a disturbing number of people on Facebook like and share articles based solely on the information available in the headline. You and I, of course, would never do that.) So question headlines are seen as best, because they provide information, but they aslo force you to click through to see what the answer to the question is.

Of course, anyone with half a brain could predict that news consumers were going to get sick of being played like that. And so now Facebook has declared war on clickbait and publishers risk losing even more eyeballs. Could this be the end of question headlines? (I refer you to the rule of thumb in the third paragraph for the answer to this question.)

Thursday Comics Hangover: Money is power

Midway through the first issue of The Black Monday Murders, a master of finance lectures a class full of eager young geniuses who are about to enter the stock market. He asks them, “you want real advice? Here it is. The first million dollars you make is self-financed. You earn it with your blood. The cost is your health, your family, your friends. You pay, understand?” It’s not quite as splashy as Gordon Gekko’s “greed is good” monologue from Wall Street, but it’s a speech that resonates with the same kind of honesty.

Written by Jonathan Hickman and illustrated by Tomm Coker, Monday is high on its own high concept: what if the top one percent of the top one percent — the wealthiest American families — understood that economics is a black magic? What if a secret society of literal financial wizards were in charge of controlling the entire world’s wealth? What if the power money holds proved to be more than just psychological?

Monday is an impressive package of a book: at five dollars, it’s packed with lots of story pages and also pages full of text and Hickman’s signature graphic design flourishes — some character dossiers, a family tree, an intriguing twist on Snopes.com, a few typographic larks. It’s a deep, immersive dive into a world that Hickman has undoubtedly outlined down to the finest detail. (Hickman has proven to be a meticulous planner; almost all of his Marvel Comics work—hundreds of comics, issued monthly over the course of years—can be read as one single story with a beginning, middle, and end.) We learn about the Caina Investment Bank, the shadowy cabal formed in the wake of the stock market collapse of 1929, and we meet Detective Theo Dumas, an unconventional police officer who is called in to investigate a bizarre murder scene in New York’s financial district.

Coker’s art is exactly right for a book like this: it’s reminiscent of the photorealism of Alex Maleev without the smoky obfuscation. Coker is a stickler for detail: the corkboard in Dumas’s office is laid out with all kinds of tantalizing hints and details that will no doubt play out in issues ahead. The elaborate murder scene in the climax of the book is portrayed unflinchingly without feeling exploitative, and the facial expressions, if a bit stolid, are clear and easy to understand. Colorist Michael Garland gives each scene its own palette, from the slightly sick fluorescent lights of a classroom to the warm, burnished wood of a multi-billionaire’s apartment.

It’s easy to be swept up in the promise of a first issue, before the story plays out and the possibilities start closing up, one after another. But Monday left me feeling hopeful for the future of the story in a way that most first issues do not: the confidence and the depth on display in this issue make it one of the most promising debuts I've read this year.

By attacking the idea of economics as a dark art with its own set of rules, Hickman opens up a world of metaphors that, to my knowledge, has never fully been explored before in comics. He could make high-level economic concepts understandable to a general audience through artful allegory familiar to almost every reader of American comic books. If any writer can successfully translate the dynamics of modern economics to popular culture via a mystery/fantasy mashup, it’s Hickman.

Mail Call for August 10, 2016

We also got a chocolate Krampus this week.

Book News Roundup: Looking for work?

Looking for a book-related job? Seattle-based publishing industry news organization Shelf Awareness is hiring a full-time publishing assistant "responsible for email newsletter ad trafficking with our book industry advertisers; direct work with the newsletter CMS; physically managing new book galley receiving, handling and shipping to book reviewers; managing other administrative tasks as assigned." They also promise unlimited free books.

Looking for an arts-related paid internship? The Seattle Office of Arts & Culture is hiring "a junior or senior college intern to assist the Communications and Outreach team in all aspects of managing the Office's events and communications, including preparation and dissemination of print and online marketing materials, pre-event planning and logistics, day-of-event onsite work and planning."

It's too late to attend the event discussed in this South Seattle Emerald profile, but you should still read about Seattle poet Natasha Marin's Reparations project.

If you like the maps in the front pages of fantasy novels or role playing games, this fantasy map generator will provide hours of entertainment.

This tweet from Books to Prisoners just won't get out of my head. Please support Books to Prisoners whenever you can; they do excellent work, and as you can see from this photo, they have to jump through some ridiculous hoops every day.

Drawing underwear on the cover of a critically acclaimed novel so that it will pass prison censors. #justB2Pthings pic.twitter.com/AS0S0r4SRI

— Books to Prisoners (@B2PSeattle) August 10, 2016

Literary Event of the Week: Cody Walker and friends at Elliott Bay Book Company

Before Cody Walker left Seattle to teach English in Ann Arbor, he was frequently described as a quintessential Seattle poet. Go to any open mic night and you’ll likely find some poet who doesn’t even realize he’s aping Walker’s schtick—an endearing blend of earnest and funny, formally inventive and respectful of tradition. For a time, Walker was a ringleader of the poetry scene, a funny and fun poet who was always willing to share the spotlight with up-and-coming Seattle writers. But even poets have to eat, and this city isn’t exactly throbbing with opportunity for those who want to teach poetry.

Walker doesn’t live in Seattle anymore, but Seattle is still on his mind; in 2013, he co-edited an anthology titled Alive at the Center: Contemporary Poems of the Pacific Northwest. And his newly published second collection of poems, The Self-Styled No-Child, is packed with the kind of poems that won him adoring crowds at the Hugo House and other venues around town on a regular basis.

Comedy and sincerity live side-by-side in Walker’s poems, and no poem in No-Child is so perfect an example of this as “A Skeleton Walks Into a Bar,” a poem named after one of the hoariest jokes of all time—“a skeleton walks into a bar, says ‘gimme a beer and a mop’”—that expands into a meditation on death. And then at the end, Walker throws his hands up in the air and surrenders:

and—fuck it, it’s just a joke. Meanwhile, move closer, Love, now that we’re both awake.

Is there a trick more noble in all of poetry than the desperate last-stanza turn from impending death to booty call? If it was good enough for Keats, it’s good enough for Walker.

On Monday the 15th, Walker will read at Elliott Bay Book Company to celebrate the release of No-Child. In typical Walker fashion, he’s sharing the spotlight with Seattle-area poets including Rebecca Hoogs, Rachel Kessler, Julie Larios, Sierra Nelson, and Jason Whitmarsh. It’s a quintessentially 2000s-era-Seattle lineup (only Ed Skoog, who himself moved to Portland not so long ago, is missing.) Sure, it’s a different city now. And sure, the face of Seattle poetry is changing — and many would argue it’s changing for the better. But listen: just because Cody Walker left Seattle doesn’t mean that Seattle left Cody Walker. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

So billionaire Paul Allen has funded a very large and very successful art fair in Seattle. Nicole Brodeur at the Seattle Times just broke the news that next year, Allen is funding a very large music festival in Seattle.

So, uh, when is Paul Allen going to get around to funding a very large book festival in Seattle? Compared to those other two festivals, this one will be a bargain to put on. Hell, I bet if Allen committed a quarter of the cost of his music festival to books, it would be one of the biggest, best literary festivals in the world — the kind of literary festival that Seattle deserves.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events in Seattle from August 10th - August 16th

Wednesday August 10: Train to Bombay

In her native India, Jaina Sanga has published a novel and a book of short stories. Though Sanga writes in English, has lived in the US since 1980, and currently resides in Dallas, her books have never been published here. Elliott Bay has imported her books and is throwing one of her only US events here tonight, making this a unique moment in international literature. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Thursday August 11: Ghostly Echoes

Now that you’ve gotten Harry Potter out of your system for a while, what are you going to read? William Ritter’s Jackaby series is about a young woman who becomes the assistant of a paranormal investigator.The third book in the series is about a ghost who hires our heroes to solve her own murder. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m. PAULFriday August 12: Finding Time

The problem with our economy, Heather Boushey argues, is it’s based on a nuclear family system in which one adult goes to work and another adult stays home and rears children, and our systems of work and leisure have never been realigned to fit the new paradigm. Find out how she wants to fix it. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Saturday August 13: Comics Dungeon Anniversary Week

All week long, Wallingford’s Comic Dungeon celebrates its anniversary with a big sale (graphic novels from 20 to 30 percent off!) Today, to help celebrate one of the best and longest-running shops in town, writer John Layman shows up to sign his delightfully weird food-obsessed sci-fi series Chew. Comics Dungeon, 319 NE 45th St., 545-8373, http://comicsdungeon.org. Free. All ages. 1 p.m.

Sunday August 14: Sherman Alexie Reads to Kids

Any Sherman Alexie event is worth your while. He’s quite simply the best reader in Seattle — funny, charismatic, brilliant. But he usually packs the biggest rooms in town; this is a rare chance to enjoy him in an intimate venue as he reads from his new children’s book, Thunder Boy Jr. Queen Anne Book Company, 1811 Queen Anne Ave N., 284-2427, http://qabookco.com. Free. All ages. 3 p.m.Monday August 15: Cody Walker & Friends

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com . Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Tuesday August 16: The Looseleaf Reading Series

Four Seattle-area writers — Natasha Marin, Suzanne Bottelli, Max Oliver Delsohn, Stephanie Barbé Hammer—and one writer visiting from California — novelist Yi Shun Lai — read new work at this ongoing literary series in Chop Suey’s den. Maybe pick up a new favorite writer or two in a nontraditional reading atmosphere. Chop Suey, 1325 E. Madison St., 324-8005, chopsuey.com. Free. 21+. 7 p.m.The boy wonder grows up

Published August 09, 2016, at 1:00pm

This Saturday, Peter Bagge will debut a collection of his earliest comics, The Complete Neat Stuff, at Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery in Georgetown. Neat Stuff tells the story of how Bagge went from a promising young talent to one of the finest cartoonists in his generation.

Remembering James Alan McPherson

James Alan McPherson, acclaimed American writer and writing educator, died last month, at the age of 72.

I studied with McPherson at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop from 1997 to '99. When we first met he hadn't published any fiction in two decades, but his kindness and his deep insights about writing drew me to his classes, and then to seek him out as a thesis advisor.

McPherson had been a correspondent for the Atlantic Magazine; in Ta-Nehisi Coates' 2014 piece "The Case for Reparations," Coates cites an Atlantic article McPherson wrote in 1974, a report on the Contract Buyers' League — an effort by a group of black homebuyers in Chicago to resist the predatory housing contracts forced on them by banks and abusive sellers. McPherson's great long 1969 article about Chicago gangs ("Chicago's Blackstone Raiders") is available on the magazine's website: for that piece, McPherson met with gang members and conducted interviews over a six-month period to create a picture of the entrenched and sometimes accidental ways in which gangs, public institutions, and churches simultaneously harmed and helped one another.

McPherson broke his two decades of publishing silence with a memoir called Crabcakes, which came out in hardcover during my first year studying with him. Now that he's passed, it has become his final book. Crabcakes is dense, wandering, floating between time periods, part history, part philosophy, part epistolary, part confession. I watched McPherson read from it to a packed auditorium at the Iowa Memorial Union in 1999, a stand-alone piece of formal satire titled "A Useful Demonstration of the Etiquette Necessary for Survival on the Secondary Roads Trailing Off the Busy Interstates During Times of Lapses in Essential Areas of Civil Responsibility, Late Summer, 1983." It's an ironically voiced recap of an interaction McPherson had with a police officer who'd pulled him over on a pretext only to discover that McPherson's registration was expired. The piece is a measured, faux-soporific "how-to" for any black man or woman hoping to survive an encounter with racist small-town law enforcement. When he read it, the audience really laughed. When I reread it this morning, I still laughed, but was struck primarily by the horror of the piece. It's as relevant now as it ever has been, in America. After the officer, with hateful language (which McPherson calls the "signal"), compels McPherson to exit his car:

Deporting, take care to not make any sudden movements toward either pockets or the interior of the vehicle. Most likely, it will be a personally interested official who will make this sort of signal. It should indicate that similar signals, drawn from the very same storehouse of vernacular expressions, are forthcoming ...

McPherson's character realizes that the challenge before him is to establish, in the mind of this officer, the existence of a common humanity between them. This lifesaving link is the key to survival, and not easily forged when a situation has begun as badly as racialized encounters with authority consistently do:

It is no longer a simple dispute between an official and an offender. It is now an exchange between the scant resources of the reptilian brain and its half-formed image of "other" which has, unfortunately, intruded upon, and blocked, its view of life in its traditional mode.

But this, the satiric voice opines, is no misfortune. Rather, it's an opportunity "for an essay at that Reconstruction which, sadly, nowadays, is so everywhere in such great need."

A big fan of Richard Pryor, McPherson once asked our workshop, "Who are the good comedians now, who tell it like it is, but are still funny?" Some people in the class had suggestions, but it was finally agreed that the world was forever poorer for the fact that it would never again have a Richard Pryor.

As with this man, my advisor, teacher, and a first-rate writer — the "great need" grows greater with each passing year, and for all the wonderful and gifted voices speaking to it, there will never be another like his.

There's Something Else

I’m an insomniac, it’s a lifelong thing. And lesbian. I’m sick when I say this, a little envious of a body that can fit through anything, a lifelong thing, steady hands but a little shaky otherwise, getting hurt in everyday ways, we joke about it, I’m sensitive. Growing up together it’s years of tangled up arms or conversations and no one touches me as an on my own grown-up but for hugs and comings and goings or across my hair when I’ve just cut it, I’ve grown all arms and head. I say to students in art class, do I look like an octopus? And when did we all know I’m gonna know you forever, and the times we were wrong and the wet weather of being teenagers or losing touch, moving back, it felt like we were fully formed forever ago sweetie. We kept returning to the ocean with varying levels of expertise.

There’s a girl freshman year I still wonder about you, I don’t want to seem vulnerable, said something about misdirecting and hiding. Her cracking, daily voice. You share so many things I’d like to think your openness hides something else you won’t tell me. I’m flooded with sudden possibilities that are in the past. I say who knows, I don’t know. Remembering her like when I finally found an octopus below me but you turn to tell your sister bobbing next to you and looking back I can’t.

I don’t know what I’m looking at and I’ll know it when I see it, I’ve known you guys forever. In my marriage I had no friends there but nowhere to be solitary, you have to share everything, it was in a roughed up old country that knew everyone else better. We had a stuffed animal octopus from some country’s aquarium in our bedroom, it could have been Australia or mine from home or some trip, as a married grown-up what do you do with stuffed animals when you want them, because IT’S AN OCTOPUS, but it’s not for anything. In the divorce, apparently I got the stingray. It’s on a bookshelf now, or maybe never see you again, ever.

After divorce I kept finding myself ranting laps in the pool, back in my own country, foreign again differently now. Could no longer say my wife to uncamouflage myself in the straight world. I’m back with my childhood friends, grown-up together who all live there now they have husbands. The other night we were laughing about the little mermaid. There’s something else.

In England, Ursula was a real name, a friend, friendly, I met her at the lesbian Uni group. Then I got married and she was my wife’s old friend and first girlfriend, my friend their friend Emily’s first girlfriend too, they had such history I just dropped into it, no one was ever solitary, we would laugh about the history all the time or just forget it. I realize later she’s a widow with children. At the pool, there were paintings on the wall that recently disappeared and reappeared more colorful, dolphins sprouting with enthusiasm out of coral and sponges but the octopus picture never came back. I never say the plural, I don’t want to look foolish unless I know you know I saw it coming and know what happened and I’m ok with it, and breezy. I don’t know if you see this in me and there’s no point in hiding. I know it wasn’t realistic but it was my favorite, a group of them orange and floating blithely in the open blue chlorinated wall.

I also worked briefly at a rare bookstore in Cambridge for a woman, forget about it, her own kind of cartoon Ursula, brutal in an impotent small way, learned to describe what kinds of books as octavo to please her but she never explained what it meant, the work ended, it’s hard to think about when I needed her job so badly. It turns out I have a few good friends back here to rush around me. I’m the only one on my own but they are here for weeks and years. This time last year I told you I was coming here and so delighted, what I learned about cuttlefish as well, my grandma just died and the weekend had to let go of everything, rush to family for something huge and unspecified, but I came out on Monday as promised. You asked about donations to remember her. The death lurking in each funny moment, and I picked up some stickers for you, and I remembered intriguing facts for you, and I also have to be reminded about the facts. The last time snorkeling was your fairy tale wedding at the beach. I had food poisoning and thought I was dying like a small child on Friday nights when your parents got divorced. I’d still go back, it was beautiful.

Now we’re all back here I think in the fairy tale version, I’d be Ursula. It’s my body, I’m a nice person. I don’t want to hurt anyone, on the phone I don’t ever say it, I just listen and laugh let her feel we could be close because she won’t notice that we’re not, why uncover myself again. I have no evil plot but I’m not the other characters. You’d be Ursula because when I came back here for visits you suddenly grew up without me, as a grown up you wear dramatic red lipstick sometimes and it surprised me then but now I live here and it’s you of course, normal and glamorous. You’d be Ursula because of the greyish purple color I see when I think of you sometimes, and weekends together, and because of your octopus shirt that I love, and you’d be Ursula a casually flamboyant performer, and wicked sense of humor anyway and we were talking about it to begin with. At the end, I realize I’m Ursula because the sound of my other dead grandmother, I felt like she was family. When I’m sick I wonder if I sound like her. Her deep mysteriously broken voice, so ordinary to me but shocking to my wife then over the phone, no future partner will know it now just throwaway moments. Thought it was a grandfather, but only her normal everyday voice like a million ordinary things breaking and settling.

When I was a kid, I loved George R. R. Martin's superhero anthology fiction series Wild Cards. It's hard to get superheroes right in prose, but Martin's dark and involved universe just felt perfect. (The comics adaptation of the books, as I recall, was terrible.) If you're going on vacation later this month and you like sci-fi anthologies, grab a couple Wild Cards volumes before you go.

Well, now that Game of Thrones has taken over the universe, a Wild Cards TV series is in the works. After watching the debacle that is Suicide Squad last week — seriously, they should show that movie in film editing classes to demonstrate how not to edit a film — I'm feeling pretty burned out on live-action superheroes. But I think Wild Cards is a decent enough mix of realism, intelligence, and inventiveness to work on tv.

A peek behind the Iron Curtain

Sponsor Isla McKetta spent a year in Poland, and it was that experience, and having spent a previous year in Pinochet's Chile as a child, that made oppression a topic in the forefront of her mind. In her novel Polska, 1994 she explores that, through the eyes of Magda, who witnesses her mother's arrest and disapearance.

We have a long sample on our sponsor's page so you can experience McKetta's tightly wrought language and ideas. See the world of this girl and how the country, and family, she's born into define her struggles.

It's thanks to sponsors like Isla McKetta, and readers like you, that we're able to keep the pixels lit up here at the Seattle Review of Books. We've just released our next block of sponsorship opportunities. Check them out on the sponsorship page, and grab your date before they're gone.

Dredding every minute of it

Published August 08, 2016, at 12:00pm

Has Judge Dredd changed over the years, or have we? Arthur Wyatt is the man who should know: he was a Dredd reader as a boy in England, and now writes for the comic.

Bookstore of the Month: Bringing authors to kids

While our August Bookstore of the Month, Secret Garden Books, does host plenty of events in its Ballard storefront, most of the events on its robust readings calendar can’t be attended by your average adult Seattleite. “What we do mostly with events is school visits,” Secret Garden’s events manager Suzanne Perry tells me. She calls the school events “one of my favorite parts” of the job, event though “we don’t publicize them and people don’t know we do them.”

Secret Garden frequently brings authors and book sales to schools around Seattle. For a long time, they did events at high schools and middle schools, but now they mostly bring books to elementary schools and even preschools. The reason is a practical one: you can’t trust older kids to remember to do their part. “For a school visit to work,” Perry explains, “you have to send a presale flier home [with the students] and they have to remember it and they have to bring it back on that day.” It’s a lot to ask of a teenage audience.

What are some of Perry’s favorite Secret Garden events with visiting authors? “Mo Willems at the Central Library was a big one for us,” she says. “He was just kind of like a national superstar” at the time of the reading. Secret Garden has hosted its share of big-name national and international authors, and they’ve had a lot of fun with them, but Perry says that ultimately “for us, the watersheds were ones where we liked the book and nobody else on the planet liked the book” because they didn’t know about it yet.

One example of Secret Garden’s early discoveries: Frank Portman, the author of the King Dork series of books. “We were the first people that liked the book,” Perry says. Secret Garden was such an advocate for Portman that “his agent sent him to Seattle” just based on the strength of Secret Garden’s sales.

Other highlights: “It was fun when Graeme Base came to the Ballard Public Library and the people who came out for him were total hipster stoner kids,” Perry says. “It seemed like he was expecting kids, but the people who came out for the reading were twentysomethings.”

And “a watershed for me was bringing David Levithan to Ballard High School.” Levithan was reading “a totally inappropriate story,” Perry says, a short story called “Smoking” that she says was “all about how sexy smoking is.” The room fell hard for it: “You could’ve dropped a pin,” Perry says. “I thought all these librarians and teachers would kill me, but they loved it.”

Her favorite part of the whole reading experience isn’t on stage at all. Perry says during school readings, especially, when you look into the audience and see the way the kids look at the authors, you can watch an inspirational moment unfold on their faces. “You can see the kids sit there and go, ‘I could have that life. I could do that.’” She says it’s a moment unlike any other: “just the recognition that they could have a creative life,” Perry says, is a big deal.