Portrait Gallery will return next week

Christine Larsen is off this week, but that only means it's a great time to go look through the amazing archive of her portraits. She'll be back next Thursday.

Kissing Books: judging the book by its...

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

A romance cover is not an image, it is a language.

Some years back, fellow author and friend Rose Lerner noticed that the Goodreads page for Cecilia Grant’s awkward-sex masterpiece A Lady Awakened had the wrong cover image attached — instead of teal satin and tumbling auburn locks, it showed a book on medieval history. In Polish. With an Extremely Serious Academic Cover. Delighted, Rose started building academic-style versions of her own book covers; a lot of other authors joined the fun, and the glorious results can be found on this Pinterest board."

The reason this was fun was that academic book covers are in many ways meant to communicate the exact opposite of what you want in a romance. They are meant to look serious, detached, and bear the weight of cultural authority. Romance, of course, is accorded none of those descriptors. It’s not news that women’s books in all genres are more likely to have feminine-coded covers no matter what the text inside says, and romance novels are the most feminized end of the cover-design spectrum. They are notoriously prone to excess: big hair, big muscles, orgasmic expressions, swooning bodies barely draped in clothing that appears to be doing a lot of swooning of its own. Unsubstantiated legend holds that the Technicolor bodice-ripper covers of the 1970s onward were designed to appeal to the men who bought titles for the big paperback distributor networks — which might explain the preponderance of mullets — but that readers came to associate the lurid covers with their romantic content and they bought so many that a marketing feedback loop was thus enshrined. In other words, they learned to read a romance cover.

But no marketing loop stays static forever, and there are now quite a few established genres of romance cover art: classic clinch covers, the headless heroine, the shirtless hero (whose pants often give a clue to his profession, like sports or soldiering), the ballgown that’s almost falling down, the long legs in stiletto heels, the hero holding babies, the tattooed leather-pants-wearing paranormal romance/urban fantasy heroine, and of course that brief wild time in the late 2000s when Fifty Shades-style covers tried to make any black-and-white image look dangerous and sexy and kinky. Tomorrow’s bestsellers will bring new trends, some of which will become fixtures and some of which will fade into history alongside colored page edges and stepbacks.

But aside from the scammers and coat tail-riders the tendency for romance covers to resemble one another is not about confusing readers, it’s about communicating with them. Cover similarities are a promise that the books will contain similar themes, or have a similar emotional impact. Harlequin made its name famous not just by publishing fast, frequent romances but by being absolutely ruthless about cover design — you can spot one from a mile away, and what’s more you know exactly what that design is offering you as a reader. Avon is subtler but no less clear: the first time I saw a Cat Sebastian m/m cover I got excited about two heroes being pictured together, then laughed because I thought some self-publisher or small digital press had borrowed Avon’s cover font (when in fact I hadn’t realized it was an Avon book, their first queer historical). Certain poses convey a great deal of information to a reader: a hero grasping the heroine’s arm from behind, for example, tells you there’s going to be a somewhat fiery, antagonistic dynamic, while two foreheads bumping gently together says the book will skew more sweet and tender in tone.

Let’s look at the cover for A Lady Awakened again, which is both utterly gorgeous and unique and a perfect example of my thesis. First, a description of what we're trying to package. The book is about a widowed country heroine who’s trying to get impregnated quickly so her terrible cousin doesn’t inherit the estate and terrorize the staff (primogeniture is a shit system). She bribes a hot rakish neighbor dude for the procreative sex, because this is a historical and sperm banks haven’t been invented yet. The early sex scenes are famously excruciating: the heroine doesn’t enjoy them in any way, and the hero’s illusions of his own prowess are somewhat painfully shattered. Eventually they fall in love and the sex turns great, but it’s a long, long haul before they get there. So this book cover has a careful line to walk: it has to suggest historical romance to appeal to the market, while warning the reader that it’s going to take a while before we get to the steamy stuff they’re looking for (because otherwise the reader will feel betrayed and this will be reflected in reviews).

We start with swathes of teal satin, hugely improbable in terms of the kind of sheets a country widow would use, but very effective in signaling “historical romance” to a modern reader. The use of teal here is brilliant, because it’s eye-catching but cool — the absence of anything resembling fuchsia is always a strong statement on a historical romance cover. The heroine is lovely, her auburn locks spread out, but notice how her arms are wrapped tightly around herself, and there is no sign of the hero? Notice as well how the colors of the cover shade into almost black, as the heroine keeps her eyes downcast and her expression wary, almost pained. She might as well have EMOTIONALLY CLOSED OFF stamped upon her forehead. This is a long and anxious journey, this cover says, and a keen-eyed reader is thus forewarned when they start the story.

You might think I’m reading into this, or reading this from the perspective of an author and a critic and not a plain reader — except that covers are always part of the conversation in romance. Cover contests and cover reveals are popular forms of promotion. Author Brenda Jackson had readers submit photos they felt would best embody one much-loved character, then tracked down the model depicted and hired him for the shoot. Most of us grew up in times and places when romance wasn’t something we could openly ask for (for safety or shame’s sake), so we learned to scrutinize cover images and cover copy closely for hints, like a hunter looking for deer tracks in the woods. (A word like “destiny” was usually a reliable sign that romance was afoot; “coming-of-age” was invariably a bad sign.) Metadata has made a lot of this easier, but it cannot sufficiently replace the visceral visual impact of a clinch or a clenching set of abs.

The saying that you should never judge a book by its cover hearkens back to George Eliot, and therefore to the days when a shelf of books were all specially bound to match one another so your aristocratic library looked nice and tidy. It's become a sort of rhetorical hammer, banging back the reality that a cover exsists as a way of speaking to the reader outside the bounds of the text. Many moralists don't want readers making choices based on personal inclination, and many authors don't want to think about their communication with the reader as something that's mediated. But when you buy a book you are often trusting it will fulfill the promises the cover has made. When you avoid a book because of the cover, it is often because you don't believe or don't want what the book cover is promising (see: every text-heavy thriller cover that hints at an unreliable narrator, shocking betrayal, and murder).

What readers do when they evaluate a book cover is not judging — it is gambling. So go on. Take the risk.

Recent Romances:

Grumpy Fake Boyfriend by Jackie Lau (self-published: contemporary m/f):

You gotta love titles that do just what they say on the tin. The greatest of these will always be Pregnesia — a book about a heroine who is pregnant and has amnesia — but Grumpy Fake Boyfriend is top-tier in the honesty department. The title makes a promise, and good Lord does the book deliver.

Grumpiness is not something I enjoy in real life, but in fiction some alchemy transmutes it into pure delight. Maybe it adds tension, as the character attempts to resist the joyful arc the book dragoons them into. Maybe it’s because grumpy characters are often blunt, and bluntness is so invigorating in narration. This book has a frank, punchy voice that had me gasping and giggling and screenshotting quotes to send to friends. Will Stafford, the titular grump, is just the right amount grouchy without tipping over into unlikeable asshole territory. He’s hermitish and reluctant and closed-off, though it’s apparent from the start that one reason he keeps those walls in place is because once someone’s on the inside of his heart he has a loyal, caring, generous streak a mile wide. His best friend Jeremy’s one of the ones on the inside, so Will can’t bring himself to say no when Jeremy asks him to attend a weekend lake house party as the fake boyfriend and buffer for his bubbly, bouncy, talkative younger sister Naomi. Whom Jeremy naturally forbids Will from sleeping with. Will doesn’t do relationships — his introversion doesn’t play well with others — so he doesn’t foresee this being a problem. Reader, I snickered, because Will is fucked.

Naomi Kwan is still reeling from a recent breakup and definitely not excited to spend a weekend in the woods with two other couples, including her ex and his brand-new girlfriend. A fake boyfriend is a ridiculous solution — unless the fake boyfriend is Will, who she’s had a crush on forever and who might be fun to take to bed. The arc here is just the right speed for a novella: light bickering leads to a little making out, which leads to a lot more than that, and bam before you know it everyone’s in their feelings. The side characters add just the right amount of drama and keep the world feeling populated. This book is a bubbly, sunny iced drink on a hot day, refreshing and tart and sweet all at once and I’m already halfway through the sequel.

I kiss her again. I softly brush my lips over hers and bring one hand up to cup her cheek, and then I’m kissing her more deeply. Showing her that yes, I do find her attractive. Very much so. She arches against me; she must be able to feel that I’m getting hard. I use tongue this time, too. More than before. “I’m practicing for our act,” I say.

She shoves my shoulder, a smile on her face. “You’re full of shit.”

Unfit to Print by KJ Charles (self-published: historical romantic suspense m/m):

They say that every generation believes it has invented sex. Certainly every generation believe it has invented new types of sex — new debaucheries, new kinks, new ways of getting off. But it just isn’t true. Humans have always been horny, ever since the days our ancestors were slapping handprints and genitalia on cave walls. So when I learned that the latest from author KJ Charles (with whom I now share an agent) was a historical suspense where one hero runs a pornographic bookshop in Victorian London, I was all in.

Men loving men was illegal in Victorian England, you’ll recall, so it’s a perfect milieu for a pair of amateur detectives. One of the challenges in mystery writing is explaining why the police aren’t the ones solving the crime: sometimes it’s because the police are unavailable (every murder mystery that takes place on an isolated island or boat or country house), but other times it’s because the police are not as interested in real justice as the amateur sleuth is (Phryne Fisher is a great example of this). Here, because the crime takes place in the context of gay sex and sex work, contacting the police is riskier than trying to solve the case. Gilbert Lawless is our bookseller, a bastard son whose half-siblings cast him out of the family after their father’s death; Vikram Pandey is a well-heeled lawyer whose upright principles and fierce morality compel him to help other Indian nationals living in London, but also tie him in absolute knots trying to cope with his own desires for men. A disappeared boy and a connection with a murder start the mystery running, and the emotional revelations quickly pile up as the plot forces the two men back into proximity after decades apart. Gil, whose past includes a stint in sex work and who’s always been better at taking pleasure while there’s pleasure to be taken, can’t understand why Vik gets so intense about their past and their entangled present; Vik can’t understand why Gil acts like what they do with one another doesn’t mean anything, and why he shrugs off chances to help other people of their ethnic background. The two have a way of just opening each other up — they are so different, and yet so entwined, and they get to the heart of the conflict so directly. Plus a view into the working-class Victorian world we don’t see often enough in romance. It’s lonely and lovely and a very little bit foxed at the edges, just like a good vintage dirty book ought to be.

Bonus points for a few slang sex terms I haven’t encountered before, but which I’m now going to drop on Twitter at the very next opportunity.

“But one can’t simply say, ‘Fancy sucking’ — you know.”

“One bloody can, in the right company. And yes, since you ask, I do.” Gil gave him an evil grin. “If you can get the words out. I’m not ‘embarking on negotiations pertaining to fellatio’ or whatever, so don’t even try.”

“Proper terminology is important,” Vikram said. “I may have to work up to it.”

Free Fall by Emma Barry and Genevieve Turner (self-published: historical m/f):

In my quest to be the World’s Greatest Expert on Astronaut Romance Novels I have developed a few working theories. For instance: astronaut romances have to emphasize the value of domestic earthbound life, to give the spacefaring hero or heroine something to come back to after the glory and risk of exploration and space travel. I don’t think this is limited to romances, either: Apollo 13, Interstellar, Gravity, and The Martian all hinge plots on whether or not an astronaut can be brought back to loved ones on earth. In earlier books of this excellent series we’ve seen a wary divorcée heroine, an astronaut’s hyper-organized wife, and an admiral’s proper daughter: in Free Fall heroine Vivian Muller is a sorority girl and the cosseted heiress of her defense contractor daddy. Vivy is a different flavor of domestic than we’ve seen before: loud, stubborn, deliberately tacky, funny, and unstoppable. A pistol, one might say, or a real piece of work if one wanted to disapprove. She had no intention of settling down — she only took astronaut Dean Garland to bed for a bit of rebellion and fun. But she ends up pregnant, her dad insists on the marriage to better his chances at landing contracts with the American Space Department (fictional NASA), and next thing you know we have the chattiest, sexpottiest, winged-eyeliner-iest heroine ever hitched to a silent, stoic, unfeeling-but-handsome-about-it astronaut who wants to go to space because it’s the farthest away you can get from another human being. They are incredibly different, drawn to each other because of it, and really, truly terrible at being in a relationship together. Watching them work it out — with strategic lingerie, home telescopes, burned dinner experiments, a puppy, and a heartrending letter at just the right moment — had me sobbing into my sleeve. This is my favorite historical series in romance right now, and we’re about to head into the back half of the series with the moon missions and the lunar lander so now is a great time to get started, if you’re new to the books. I cannot wait.

They’d gone from probably never seeing each other again to being married. The significance of the shift sat between them like a sunning walrus.

From Scratch by Katrina Jackson (self-published: contemporary pan m/bi m/f):

I am sorry I did not see this book when it was hot off the presses last December, but better late than never because this one is really something special. Inclusive ménage romance set in a small town, where all the drama comes from the careful navigation of personal relationships and intimacy? Smoking hot sex scenes, caring hearts, and baked goods? This is someone’s Absolute Catnip and I want them to have the chance to hear about it.

They say time is a river, and this book believes it: the voice is loose and conversational and flows backward and forward from one moment to an earlier then on to the next. We start with curvy heroine Mary, who’s just lost her hateful academic job and decided what the hell, starting over as a baker in a small town looking for a population boost might be a much better fit. She brings donuts to the Sea Port police chief — Miguel Santos, ex-Marine, principled, hot — while he’s having coffee with his best friend the fire chief — Billy Knox, ex-Marine Sergeant, abusive family, uses humor like a shield, also hot. The chemistry of these three was enough to fry an egg on my e-reader. Their attraction to Mary helps reveal the two men’s long-simmering, equally long-hidden attraction to one another, and when Mary confesses that for a solid week she’s been dreaming of having both of them, with her, together — well, it is, as the kiddos say, on. The sex is frank and filthy and sweet all at once, and the emotions are rich and layered and well worth watching. It is just such a damn comfort sometimes to have romance characters who act like adults, even when it’s difficult, even when feeling out a new relationship that the culture doesn’t really have a blueprint for. This book is incredibly light on the conflict — but in a way that feels like a kindness to the reader, which is something I have come to cherish in these trying times. There will always be room in my heart (and in this column!) for pure fluff, served piping hot.

Santos wasn’t an idiot. He knew she wasn’t just talking about Knox, but he needed to hear her say it, because none of this made sense. This was not what good, straight-laced cops and bakers did. Right?

This Month’s Hardcore Historical Who’s Having None Of Your Shit Colonialism:

Duke of Shadows by Meredith Duran (Pocket Star: historical m/f):

Another thing this column always has room for: romances that stare unflinchingly into the void. Because hardened survivor souls need love as much as the tender, trembling ones.

Author Suleikha Snyder has said more than once that this book is one of the best historicals she’s seen set for depictions of British India, and on its ten-year anniversary its power remains intense. It is too vivid a mirror at this moment to read about an angry country at the boiling point, with a terrible event looming in the very near future. Heiress and artist Emmaline Martin survives the shipwreck that kills her family on the way to Delhi only to learn her colonel betrothed is already cheating on her with other officers’ wives. She takes refuge in the garden at a party and meets part-Indian, part-English Julian, Marquess of Holdermann and future duke. Both are frustrated, hurting, and angry, so their flirtation is born as much out of that as out of their undeniable attraction — and they barely have a moment to reflect on what they’re feeling before the Indian Mutiny hits and things go absolutely to eight kinds of hell. What follows is absolutely horrifying, a nightmare of near escapes, murder, sexual assault, mutilation, guilt, and betrayal. We resurface in London: Emma is broken and only barely holding onto her sanity, compulsively painting her worst memories of her escape. Julian thinks she’s dead, until he comes face to face with her at an art exhibition — and realizes her paintings hold a terrible secret. It takes them the rest of the book to work out what they’ve gone through, what they’ve done, and what they mean to one another. My soul bled for them the whole time — especially Emma, whose self-isolation by trauma is one of the most devastating things I’ve ever read in a romance. As for Julian, caught between two cultures violently opposed to one another, he has turned code-switching into a whimsical kind of bitterness that both unsettles and fascinates. Their banter is often uneasy and cutting, but it’s abundantly clear that nobody will ever understand them better than they understand one another. They’re never going to be light-hearted, but they’re so damn strong, and they value each other so deeply, that the HEA is totally, utterly convincing. This is one of those romances that leans into the darkness rather than shutting it out, and is all the better for it — much like the characters it brings to life.

The ocean waited too. It sulked sluggishly beneath the tropical sun; slipping into it would not be so hard. The heat felt like a warm hand pressing on her back, urging her down and away. No trace of the great ship remained; no one surveying these flat, empty waters would suspect what had passed here. No one was coming for her. But her hands would not let go.

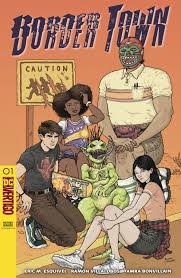

Thursday Comics Hangover: By the time I get to Arizona

Monthly serialized comics are a relatively fast-moving medium. If a team on a book is really humming, they can create a title and get it on the stands in a matter of months. That seems to be the case with Border Town, a new Vertigo title whose first issue was just published yesterday. Written by Eric M. Esquivel and illustrated by Ramon Villalobos, Border Town feels as current as the day's headlines — for better and for worse.

Pretty much every page of Border Town references some aspect or another of the Trump Administration. The first page features a bunch of xenophobic white Arizonans firing machine guns into the air and shouting "MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN, MOTHERFUCKER!" But in Border Town, current events are pumped up and made into monsters and paraded through the streets. The town of Devil's Fork, Arizona is being haunted by modern American specters: a white woman is terrified by a figure that looks like a black teen, a man runs from a green-skinned ICE agent, someone else recoils from a giant "tiki-torch Nazi" with sharp teeth roaming the streets. It's the American nightmare in a Halloween mask — or maybe with the mask removed.

None of this relevancy would matter if the comic was ugly. But Villalobos makes reading Border Town a pleasure. He's from the Geoff Darrow school of comics art — the noodly, hyper-detailed work that rewards repeat viewing. (The first issue features cameos from Sandman and an especially beloved Superman story.) And colorist Tamra Bonvillain is doing some stunning work here — the color pallette of the book tracks a single day, from night to dawn to noon to dusk to night. The light in Arizona glows warmly, but all those oranges and reds and blues could just as easily represent a bruise.

It remains to be seen if the plot of Border Town will rise above some pretty standard "there is a pierced vale between this world and the next" supernatural potboiler drivel, but the quality of the art in the book, and the cleverness with which the creative team addresses contemporary topics, will keep me coming back regardless.

The magic kingdom

Published September 06, 2018, at 10:01am

Last night, the Reading Through It Book Club discussed America's weird relationship with fantasy, and the way Donald Trump has taken advantage of our national love of delusion.

Book News Roundup: Type Set is hiring, Richard Chiem's novel has a pretty cover

- On her Facebook page, Mayor Durkan last night eulogized B. Bailey Books and Bailey/Coy Books cofounder Barbara Bailey. Durkan praised Bailey for creating "nationally beloved independent book stores" which served as "safe and welcoming spaces for the LGBTQ+ community." She continues:

In Barbara’s bookstores, there was no shame and nothing secret or hidden – “our” books were placed prominently next to all the New York Times best sellers. Barb warmly welcomed everyone to the store, often loudly with a laugh, a hearty greeting or an exclamation about the latest political outrage.

Type Set, the writer-centric coworking space in Columbia City, is looking for a community and social media manager to manage member relations, work at the front desk, engage with social media, and plan events. It's a part-time gig, starting at 15 hours a week or so.

The cover of Seattle writer Richard Chiem's debut novel, King of Joy, is goddamned beautiful:

- These useful lessons for authors who are reading their own audiobooks could also apply just as easily for authors who are learning how to read their own work aloud in public.

Talking new fall titles with one of Seattle's best booksellers

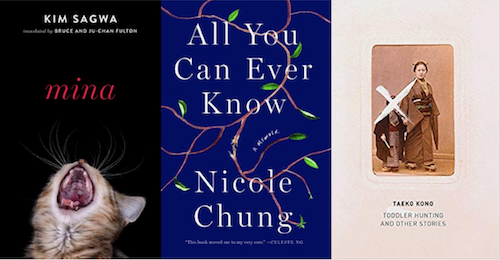

Caitlin Luce Baker is one of Seattle's very best booksellers and one of the most avid readers in the city. She works as a backlist buyer at University Book Store, which she helpfully explains to me over the phone means she's in charge of making sure the bookstore carries "the books that came out last week, and the books that came out fifty years ago." Caitlin frequently represents the city at national programs — she's currently a judge of the 2018 Best Translated Books Awards — and she always reads months into the future.

"I probably read 12 to 15 books a month on average," Caitlin says, and she tracks every book she reads by noting them on three-by-five inch index cards. All those books you're dying to read this fall? Caitlin probably read most of them months ago. (She's an excellent Twitter follow as well.)

So what fall titles are Caitlin most excited for you to read? The first book she recommends is a short story collection by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah called Friday Black, which Caitlin says "blew me away. He's a dramatic new voice," she says, and "there's not a weak story in the bunch."

Caitlin calls another upcoming collection, Toddler Hunting and Other Stories, by Taeko Kono, "unsettling and obsessive." The title story, she says, "is about a woman who loathes little girls, but is always buying expensive clothing for little boys of acquaintances." Kono is interested in crossing boundaries and violating taboos, and Caitlin warns that "each story in this collection is dynamite."

"Absolutely one of my favorites" of the upcoming fall titles, Caitlin says, is a novel titled Samuel Johnson's Eternal Return, by Martin Riker. It's "the story of a father's love for his son" that "traces the history of television in America." At the beginning of the book, everyone watches the same three or four channels, but by the end those choices have fragmented into "a zillion channels," which results in a kind of loss of community.

Another novel that was just published yesterday, The Golden State by Lydia Kiesling, looks at another angle of parenting. "It's a road trip novel, but it's different — it's a road trip with a 16-month old baby," Caitlin says. The book is about a woman whose husband is Turkish, but "due to US policy and visa issues, he's back in Turkey." Life as a single mother becomes overwhelming, and "she takes off in her Buick to a small town in California," where "she meets a woman who lived in Turkey when she was younger." Caitlin especially admires this book for its timely investigation of "questions of American immigration."

Caitlin calls Mina, a novel out on October 10th by Kim Sagwa and translated from the Korean by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton, "one of the rawest and most honest depictions of what it's like to be a teenager" that she's ever read. "This book takes it to extremes," she says. "There's a screaming kitten on the cover. I don't want anyone to pick up this book because it has a cute cat on the cover — that cat is screaming for a reason," Caitlin warns. "This book kind of blew me away."

The fall brings with it some vivid first-person accounts that will open readers up to new perspectives. One of the titles that most appeals personally to Caitlin is Shaun Bythell's Diary of a Bookseller. "It is hysterical," Caitlin says. "Anything that anyone ever wanted to know about what a bookseller really thinks is in here." It's about the owner of a bookshop (named The Bookshop) in Scotland and his relationships with customers.

As much as she loved Bythell's memoir, Caitlin says of Nicole Chung's All You Can Ever Know, "if you read one memoir this year, read this one." She says the language in the book, which is about Chung's experience as a Korean girl who was adopted by a white family in a lily-white Oregon town, is "beautiful." Chung took the solitude of growing up where "no one around her looked like her" and channeled it into an intense memoir that investigates race and identity.

After talking on the phone with Caitlin about upcoming releases for a half an hour, she sent me a followup email with upcoming poetry titles that she wants people to know about — The Carrying by Ada Limón and feeld by Jos Charles, both from Milkweed; and Perennial by Kelly Forsythe from Coffee House. Her exuberance for the titles is infectious. For the better part of a year now, she's been waiting for readers to be able to get their hands on these books, and finally the time has arrived. For a dedicated bookseller like Caitlin, fall book season is one of the very best times of the year.

Book News Roundup: We've got some world-class translators here in Washington State

Last week, the NEA announced $325,000 in grants to support the translation of world literature into English. At least three of the winners have local ties! Congratulations are in order for Ian Boyden of Friday Harbor, Stefania Helm of Bellingham, and Lola Rogers of Seattle. Please allow us to boast: Rogers wrote a great piece for us at the Seattle Review of Books about translating the work of great Finnish novelist Johanna Sinisalo.

The downtown branch of Seattle Public Library has installed phones for homeless patrons, Ashley Archibald reports at Real Change.

People experiencing homelessness are as reliant on phones as any housed person, perhaps more so. People have to call in to remain on waiting lists for housing and check in with shelters at night. The directory to connect people to services — 2-1-1 — is available by phone.

The phones are limited. Users are restricted to 10-minute calls to local numbers — numbers with the area code 206 and some 425 and 253 numbers — and while patrons can make calls, they cannot receive them.

Seattle writer G. Willow Wilson's comic series Ms. Marvel has officially sold a half-million copies in trade paperback. That's a lot of comics.

Because the Nobel Prize in Literature was stained by a truly gross sexual harassment scandal this year, someone has launched a "new Nobel Literature Prize." Unlike the, uh, old Nobel, this committee announced a shortlist of Haruki Murakami, Neil Gaiman, Kim Thúy, and Maryse Condé. The winner will be announced in the middle of October.

If your long weekend started early, you might have missed the news that the Village Voice has officially folded. Except for a few stragglers in big cities, alt-weeklies are pretty much dead in America.

30th Birthday Poem

Warm dusks too hot to sip anything

but rum and look north & north & northlike cold nights when the aurora glows.

Meatballs, size of a small river stone

hand curved, roasted & frozensaved like speckled marbles in a jar.

Cattails bent over their pond

as if signing a mortgage.Driftwood waving her wild bone

arms at the end of the seaas if she untangled from nowhere, with

everywhere sprouting from her fingertips.Boy perched on the rock above the cliffs above the river,

the second his pointed toes depart the rock.The dive & the cold.

His wet head above the eddies.The now & the now & the now

like the filly, top lip stretched so far above the brambles,stomping to ram her fragile adolescent

chest against the fenceas if she could close the last hovering inches

between the taste of blackberries& empty air.

Spend Nov. 18 with Neil Gaiman — then spend Nov. 19 with David Sedaris

Returning sponsor Northwest Associated Arts is here this week to make sure you have a chance to reserve seats before they're gone. And, of course, tickets for both events are going fast. Gaiman is almost universally beloved, and his scope is huge, so he draws readers from across genres. Sedaris is a Seattle favorite, and he returns regularly to test new material against our, ahem, discerning ears.

Get more information about both events on our sponsor feature, then buy tickets for both. It's a rare chance to be surprised and delighted, in two completely different ways, two nights in a row.

Sponsors like Northwest Associated Arts make the Seattle Review of Books possible. We're almost sold out through 2018 — there are only four slots remaining! The fall sold out incredibly fast, so grab this chance to get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from September 3rd - September 9th

Monday, September 3: Labor Day

Happy Labor Day!

Tuesday, September 4: Night and Silence

Seattle fantasy author Seanan McGuire's October Daye series of novels is about a woman torn between the human world and the world of the faerie. Her latest novel, Night and Silence, sees Days reeling from recent events. When an estranged member of her family disappears, she starts down a newer, darker path. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, September 5: Reading Through It

On the first Wednesday of every month, the Seattle Review of Books co-hosts a book club at Third Place Books to talk about current events, history, and the culture of why America is as screwed up as it is. Tonight's book, Kurt Andersen's Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire: A 500-Year History, is at once current events, history, and a cultural story. Andersen explains our country's long relationship with hucksterism, from P.T. Barnum to Trump.

Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Alternate Wednesday, September 5: Assembly

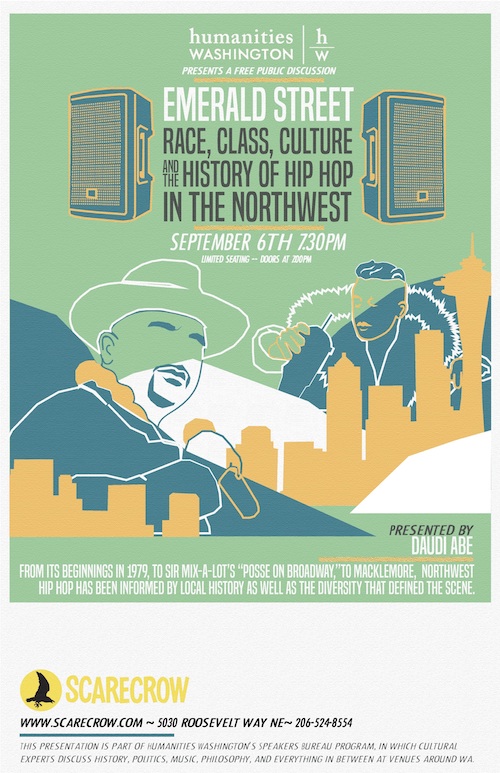

Whenever we recommend a SRoB- adjacent event, we always try to offer you an alternate event on the same day that doesn't have a conflict of interest. Assembly Open Mic is a reading series curated by local DIY literary powerhouse Kate Berwanger, who I interviewed last month. It's a supportive environment intended for authors just starting out to share what they've been working on, and there's booze around for you to enjoy. Screwdriver Bar, 2320 First Ave, 485-7116, http://www.screwdriverbar.com, 7 pm, free, 21+.Thursday, September 6: Emerald Street

As a lecture accompanying a film subtitled Race, Class, Culture, and the History of Hip-Hop in the Northwest, Seattle author Daudi Abe discusses Seattle's distinctive hip-hop history and what it says about our region. If you think Macklemore invented rap in Seattle, you are in dire need of an education. Scarecrow Video, 5030 Roosevelt Way NE, http://www.scarecrow.com/, 7:30 pm, free.Friday, September 7: Kickdown Reading

Visiting author Rebecca Clarren is in Seattle to read from her debut novel, Kickdown. It's about sisters whose rural lives turn upside down when an Iraq War veteran enters their orbit. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Saturday, September 8: Pistil Books

If you've lived in Seattle for a couple decades or more, you likely remember a small Capitol Hill bookstore called Pistil Books. Located near the Wild Rose, Pistil was a small but well-curated bookstore with a good selection of zines. Though they still sell books online, for one day a year Pistil reconstitutes in the form of a physical bookstore, as the owners sell used books in a giant yard sale, with books selling for one or two bucks a pop.Pistil Books, 1415 E Union St, http://www.pistilbooks.net, 10 am, free.

Sunday, September 9: Poetry of Place with Laura Da'

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Public Library, Capitol Hill Branch, 425 Harvard Ave E, http://spl.org, 2 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Laura Da' teaches "Poetry of Place"

In Seattle poet Laura Da's great poem "Passive Voice," she reflects on teaching kids to avoid passive voice using that old trick:

Circle the verbs.

Imagine inserting “by zombies”

after each one.

Of course, if the sentence works with "by zombies," it's in passive voice. But that's not the point of the poem. She goes on to imagine those kids on their summer vacations, traveling the country "on the way home/from Yellowstone or Yosemite." She pictures them getting some fresh air, addled by hours in the car, witnessing roadside attractions.

How she ties these two images together — the passive-voice zombies and the sun-baked highway monuments — is immensely pleasurable and I won't ruin it by summarizing it here.

The interesting thing about the poem is how Da', in a few short lines in the middle of a poem, places the reader so solidly in a place. You don't just imagine the summer road-trip pitstop. You're in it, you're there.

This is a rare talent in a poet. Too often, poets will fail to remember to anchor their poems in space and time, leaving the reader afloat in a mysterious gauzy nowhere. Da' never fails to remind her readers where they are.

That's why she's the perfect teacher for a free class called "Poetry of Place," which is happening in the Capitol Hill branch of the library this Sunday. Da' promises to help her students "look to land and water ways as a source of poetic inspiration."

Whether you're a poetry novice or a published author, this (free!) class is for you. All it costs is two hours of your life. Students are asked to bring a pen and paper or a laptop to write on. Da' will do the inspiration. No maps required.

Seattle Public Library, Capitol Hill Branch, 425 Harvard Ave E, http://spl.org, 2 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for September 2, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The New Reading Environment

Writer, editor, reader. On the internet, the small sins of each add up until real communication is impossible. The editors of n+1 have a thoughtful piece that looks at how a new way of reading — in which we’ve all become like that annoying boor at a party who listens only with an ear to what he’ll say next — shapes what gets published and how.

This is such a good call to action to all of us: to remain alert, to remain thoughtful, not to let “outrage is a sign of consequence” be the register in which we read.

To be a reader is to suffer. The endless call-and-response that leaves writers forever relitigating their work . . . all this is for our sake? In the not so distant past, we could sit with an article and decide for ourselves, in something resembling isolation, whether it made any sense or not. Now the frantic give-and-take leaves us with little sovereignty over our own opinions. We load up Twitter to discover some inscrutable debate (“Why is everyone fighting about the Enlightenment?”), usually over a series of misinterpretations, which in the space of an hour or two has ended friendships and caused major figures to leave the platform.

Stephen Colbert connects Chance the Rapper & Childish Gambino to the Lord of the Rings

Hat tip to Jason Kottke for linking to this utterly charming short video of Stephen Colbert drawing a throughline, with immense passion and slight sheepishness, from the prosody of Childish Gambino through Gilbert and Sullivan all the way back to Tolkien. Don’t think you want to watch video this morning? Can I change your mind by pointing out that Colbert recites lines from all three?

Kottke is a bit hard on Colbert’s use of the word “rare” to describe the particular pattern his ear picked out. I’d gently submit that there’s a lot more to rhythm and rhyme than, well, rhythm and rhyme — the unique earprint of a line of verse or song is made up of the interaction of so many sound patterns and its emotional tenor and the experience and trained or untrained ear of the listener. In other words, Stephen Colbert is clearly right, and Jason Kottke is clearly, and I never thought I’d say this, wrong. (But “superbly nerdy” — yes indeed.)

I wonder about the “rare” bit though . . . rappers packing songs with internal rhymes is not a new thing nor is referencing Gilbert & Sullivan in hip-hop. Still, this is superbly nerdy.

The Allure of the Rose and the Bow

In a very few words, Emily Schulten perfect captures the waking-in-Eden devastation that happens when a child learns her body is shameful, and even more poignant, that she isn’t the one who defines whether it is or isn’t.

When I leave the bedroom, I stay close to the hallway’s stone wall. Back upstairs, I take my time. I look at the tangled elastic and stitching of the bra, the X-patterned front of it. I pick it up, feel its weight between my fingertips. I hate it. I unbutton my uniform, pull a binding across one shoulder, then the next, contort one shoulder toward my ear and around to my back to make the tight straps reach. I fold both arms behind my back so they will meet to fasten the eye-hooks. I can feel the weight of the thing. It’s heavier now.

Whatcha Reading, Kim Brooks?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Kim Brooks is the Chicago-based author of Small Animals: Parenthood in the age of fear, her just-relased memoir exploring of modern parenting, and the novel The Houseguest. She's appearing in conversation with local writer and memoirist Claire Dederer at the Elliott Bay Book Company, this Tuesday, September 4th.

What are you reading now?

Right now I’m reading and loving Rebecca Makkai’s The Great Believers, a historical novel chronicling the multi-generational trauma of the early years of the AIDS epidemic. In nonfiction, I’m reading The Way We Never Were, Stephanie Coontz’s history of the nuclear family in America, as well as Jacqueline Rose’s, Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty.

What did you read last?

Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream by Andrés Duany, Elizabeth Plater Zyberk, and Jeff Speck, Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and bell hooks’, All About Love: new visions.

What are you reading next?

Rebecca Solnit’s Call Them By Their True Names, Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, and for something a little lighter, Ling Ma’s, Severance, which I’ve been told is a very funny and brilliant satire about the end of the world.

The Help Desk: Going postal

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

A bunch of friends and I were out drinking one night and we realized that we all had stories about passing dirty novels around in elementary school. Usually ones like Judy Blume's Wifey, since my parents thought all Judy Blume books were for kids. But other friends said Piers Anthony, one friend even claimed The Story of O was the hot property in her school, but when caught they told the ignorant teacher it was about a girl named Olivia who loved a dog that bit people.

Anyway, I was wondering if you have a story like this, first. And second, what books do you think kids today pass around?

Curious since pre-puberty,

Vanessa, Out by Carkeek

Dear Vanessa,

No one but a pervert could describe mine as a normal sexual awakening. Around puberty, I plucked a copy of Love is a Dog from Hell from my mom's bookshelf and from it learned that mailmen fart better than they fuck (to paraphrase). When my grandmother caught me reading about asses that never age and semen free-flowing from hookers' thighs (to paraphrase), she overcorrected by giving me a copy of a 60s romance novel set in a post office, filled with endless "package" euphemisms that further reinforced the horniness of mailmen. (For years, I described budding desire as "mailman feelings.") Then, for my 13th birthday, someone bought me The Joy of Sex, which taught me the mechanics of the female orgasm and how to appreciate the boldness of a well-coiffed bush. None of my friends wanted anything to do with any of these books. All of them had sex before me but none of it was described as joyful or involving the USPS.

As to your second question, I don't have to guess what kids are sharing these days – I have a 14-year-old sister and a 12-year-old brother and neither of them appreciated my attempts to lend out my copy of The Joy of Sex or talk through their complicated mailman feelings. Judging from their social media feeds, sex-ed has evolved from covertly reading soft-core stories to following soft-core social media stars whose nipples have their own #sponcon deals. While I envy the ease with which today's youth can explore their sexuality online – eliminating much of the covertness and for some, fear and shame – reading about sexuality allows readers to develop their own desires rather than embracing the same bushless, overtanned images of what constitutes conventional attractiveness. (For instance, have you ever noticed what great calves postal workers have? Yet my search for #postalworkerporn yields no results on Google.)

Fortunately, the New York Public Library recently announced a campaign to bring literary classics to Instagram... perhaps some day they can be persuaded to add coming-of-age classics like Wifey and Love Is a Dog from Hell to the mix as well?

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Kate Gavino

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday, August 30: Sanpaku Reading

Kate Gavino is the cartoonist behind Last Night’s Reading, a blog featuring cartoons about author events that was then turned into a book. She’s giving a reading of her own, of a new fictionalized comic memoir called Sanpaku.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Won't you take me to Poochytown?

Jim Woodring isn't just creating a new world in his wordless Frank series of comics — he's designing an entirely new vocabulary. The Frank comics take place in the Unifactor, a densely illustrated cartoon world with its own laws and distinctive life forms. The main character is Frank, a generic cartoon character (Is he a cat? A mouse? Why is his face so...scrotal?) who comes across as a Chaplinesque innocent — albeit one with a vicious mean streak.

Every new Frank book changes the Unifactor in some way or another, adding a new element to the formula and playing out the scenario to see what happens. In the last book, Fran, Frank met up with a feminine version of himself, and the resulting interactions nearly destroyed the Unifactor.

In Woodring's latest volume, Poochytown, Frank's sort-of pets Pushpaw and Pupshaw climb into a higher plane created by a deranged musical instrument. Without his companions, Frank becomes lonely and eventually befriends his longtime enemy, the unsophisticated and hideous Manhog. The adventure involves a horse that chews off Frank's limbs, a visit to a location that resembles Woodring's studio, an out-of-body experience inspired by someone battering their head against a locked door, and one of the most heartbreaking emotional turns in the series thus far.

It's possible to read the Frank books as the comics version of silent movies — Woodring decorates all the stories with slapstick and visual gags and amusing side-quests — but they are seething just underneath that cartoony surface. Woodring is exploring primal concepts like religion and consciousness and community.

And while the surface elements of the Frank comics are just as beautiful as ever (Poochytown features some of the most breathtakingly intricate pages of Woodring's career, which is really saying something,) that deeper existential level feels as though it's growing more frenetic with every new volume. Poochytown enjoys the same moseying pace as the rest of Woodring's stories, but the inquiries he's making here on a philosophical level feel as dark and cutting as anything he's ever written.

No prior familiarity with Woodring's work is necessary to enjoy Poochytown, but after reading the book you might feel a certain anxiety roiling deep inside. That's not a mistake. More than any literary novel I've ever read, Woodring's Frank comics accurately portray the stresses and disappointments and horrifying wonder of what it is to be alive. And as being alive becomes more and more terrifying in the early part of the 21st century, Woodring's art reflects that terror right back at the reader.

While Borders disappeared with a whimper, it seems that Barnes & Noble isn't going to die without some drama. Former B&N CEO Demos Parneros has sued the bookselling chain for wrongful termination. His lawsuit alleges that B&N was nearly sold to another corporate bookstore chain this summer. B&N, meanwhile, alleges that Parneros engaged in "sexual harassment, bullying behavior and other violations of company policies." If you want to read more, Shelf Awareness this morning published a great account of the ugliness on both sides. This story isn't going to get any prettier as B&N continues to circle the drain.

Don’t Read THAT, Read THIS

Published August 29, 2018, at 12:00pm

Trim page counts to fit the times, says Ivan Schneider: Don't read Vollmann, read Tawada. Don't read Canetti, read Franzosini. Don't read Andersen — learn Spanish.

Elizabeth Austen is finding clarity by embracing mystery

I've been following Elizabeth Austen's work for years now — from her early chapbooks to her 2012 debut collection Every Dress a Decision, from her role as Washington state's third Poet Laureate to her role as a poetry correspondent for KUOW. Her poetry has always been accessible enough to capture a reader's immediate attention, but durable enough to reward multiple readings with new discoveries. She's a complex writer who constructs levels in all her poems.

The four poems Austen contributed to the Seattle Review of Books this month as our Poet in Residence, though, feel different somehow. It's not that Austen doesn't sound like herself — that voice is as clear and confident as ever — but the rhythms of the poems feel different, and there's a mystery to the new work that departs from her previously published material.

On the phone, Austen admits to being "relieved" when I ask her if there's a difference between her new and her old work "because they seem different to me. And I want them to be different." But she's not entirely clear on what the difference is, either.

In many ways, Austen is just recovering from her time as Poet Laureate — a role that awkwardly fuses the sociability of a politician with the introspection of a poet. Austen was a tremendous advocate for local poets and a very effective conduit between ordinary Washingtonians and the literary arts. But she says her two years in office were "draining in a way that I don't think was possible to anticipate." Austen says she "loved" being Poet Laureate and "I was grateful to get to do it," but she confesses that "I needed about two years of quiet" when her term was over.

Of course, nothing has been quiet about the last two years. Austen says her newer work is "partly dictated by the times we live in." Since 2016, she's been "feeling silenced by my own sense that poetry seems an incredibly paltry response to the state of the world."

This isn't just about a Seattleite despairing at Trump's election. Austen says her poetry was silenced in the face of "the resurgence of something ugly that I thought was a lot closer to its deathbed: overt racism, overt misogyny, this incredible xenophobia and anti-immigrant insanity."

After months of feeling helpless, Austen says she came to terms with her responsibility as a poet: "I finally just gave in and realized that it may be paltry, but it's what I have to offer."

As a reader of poetry, Austen says, her needs have changed. "I need poems that speak to the moment we're living in," that provide a context to modern American life as part of a continuum of history. Who does she read for inspiration? "Danez Smith and Terrance Hayes are two poets that are just continually rocking my world in terms of what they managed to do with the clarity and imagination with which they're meeting the moment." She credits Ada Limón for being "willing to hold the heartbreak of moment."

But in order to find her inner voice again, Austen has had to reach outside herself. "It feels very practical when I bring poems to groups of people who, for example, do palliative care or who work with people who are unhoused," she says. (In her day job, Austen works as the senior content strategist at Seattle Children's Hospital.) "The value of poetry feels very urgent and very tangible to me because I see it through the eyes of people who don't have the kind of everyday access to poetry that I do." By sharing poetry with people who are experiencing grief and trauma, Austen remembers why poetry matters.

And what does she do when she actually needs to sit down and write? Since 2016, she says, "the big change in my process is that I do most of my initial drafts now with one other writer in the room with me. I meet once a month with Kathleen Flenniken and once a month with Susan Rich." The poets coax each other along the creative process. "We give each other prompts, we do timed writing, and then we read aloud whatever we wrote. That's how a lot of my new poems have started, really, for the last two years."

That support network has helped Austen immeasurably. "In many ways, the two of them kind of carried me through a time of feeling like I really had kind of forgotten how to write."

The new process is definitely having an effect on her work. "I'm very purposefully trying to set up situations where something will arise that is beyond my conscious control. Where my first book had a very definite narrative spine that was clearly autobiographical, I'm trying to do something here that is probably much more ambitious."

You can see that in the poems Austen has published with us this month. "Shall Not Be Infringed," she says, came during an exercise when the poets exchange the end lines of poems. Borrowing words from another poet "pushed me in a particular direction," Austen explains. "I followed where they went and at the end of it realized something I had been percolating about, and probably even dreaming about."

Her poem "[ ]" is "an experiment" in "how much I can leave unsaid and infer and leave room for the reader." This poem, along with several others in the manuscript Austen's working on, grapple with "a kind of hideous, cyclical mess to certain kinds of news — certainly news of shootings." She says "I wanted to convey that sense that there are so many different names that could go in those brackets."

Finally, Austen seems able to communicate what's different about her new work: "I'm a lot more willing to include in the poem things I can't rationally account for." She wants to capture something that is "a little bit beyond my reach." All of Austen's new poems interact with that energy, that mystery, that gap between reality and aspiration. At a moment in which poetry felt weak and ineffectual, Austen started down a path that led her to an exciting new strength.