Comics days - Kickstarter Fund Project #7

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

Comics days. We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer

Who is the Creator?

Kristina Vilciauskaite Shephard.

What do they have to say about the project?

Comics days in Vilnius is the first international comics festival in Lithuania that will be held on 14 - 16 of April 2016.

What caught your eye?

Independant comics festivals are the best. It's important for creators to have a place to gather and share their art, and talk to like-minded people to learn and make community. Think about how vibrant our own Short Run Comix and Arts Festival is.

So here are some folks trying to stage an international comics festival in Lithuania, called Comics Days, and it will be the first of its kind over there. That's a project we can get behind.

Why should I back it?

I'm guessing most of you reading this aren't in Lithuania, or aren't planning to visit for the festival. So, this raises the important question: what's in it for me?

Art and comics! Look at their rewards. For as little as $5 you can get a sticker pack. There are posters, comics, and even original art. And the branded gear is beautiful, as are the posters. I know a few of you reading this salivate at the idea of some rare, cool foreign art in your collections. Here's your opportunity to snag some.

Not to mention you're helping creators overseas get their community going. That's worth a few bucks.

How's the project doing?

21 days to go, and they've only raised about 18% of their $4,500 goal. So, they need the help. Pitch a bit in, let your friends know — those emails that a friend just backed a project on Kickstarter are pretty powerful. Let's see if we can't give them a little bit of a boost.

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 7

- Funds pledged: $140

- Funds collected: $80

- Unsuccessful pledges: 0

- Fund balance: $900

Italian news sources are reporting that author Umberto Eco has passed away. He turned 84 years old last month. Eco is the author of two global bestsellers: Foucault's Pendulum, a playful conspiracy thriller; and The Name of the Rose, a murder mystery set in a Benedictine monastery. I especially enjoyed Eco's underrated 2004 novel The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, a deeply personal tribute to the comics and pulp literature of Eco's youth, as well as a rumination on memory and aging. Eco's novels were always fun and elegant and rewarding on multiple levels; he created beautiful labyrinths.

Between this news and Harper Lee's passing, this has been a very sad day for literature.

Against longform

Alex Balk at The Awl published a brief post against longform nonfiction storytelling. Here's a quote from the piece, which I think gets the point across with even more brevity: "Are there some stories so intricate that they actually demand tens of thousands of words to tell them? Sure. Maybe six or seven a year. Everything else you read is padding or awards-bait."

It's purposefully incendiary stuff, and obviously a broad generalization. Personally, I tend to prize pieces of a certain length; here at the Seattle Review of Books, we rarely publish reviews that are shorter than a thousand words, because we think anything less tends to fully fail to develop an idea. I recently wrote a piece for the site that was over three thousand words, but I hope to cut it down a little bit in the editing process.

But in general, I tend to agree with Balk; I've read a lot of longform pieces that have wasted my time. I'm fine with digressions and taking your time to tell a story, but a story should be exactly as long as it needs to be. We've all read magazine articles that have been puffed out to book-length; we all agree that those are terrible. When that happens, we feel manipulated, and it sours the reading experience. Same with longform. That said, I am always in favor of more writers writing more, and if longform is the vessel that gets readers in front of writing, that's a-okay with me.

But rather than arguing about a nonexistent perfect metric for exactly how long a piece should be, I'd rather everyone read this great post by Chuck Wendig about why paying writers is so important. It's titled "Scream It Until Their Ears Bleed: Pay the Fucking Writers," and it's in response to an idiotic Huffington Post editor's bullshit claims that paying writers is "not a real authentic way of presenting copy," that because Huffington Post bloggers write out of passion, their writing somehow has more merit. I don't know how many words Wendig's post is, but I can tell you it's exactly as long as it should be.

The Help Desk: Tintin is a racist and I don't know what to do about it

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I absolutely love Tintin. I have since I was a kid, and still just fall for his outrageous antics. But oh my god, is it racist. So horrible! And, you know, all about white conquest. Do I have to give him up?

Minnie, Belltown

Dear Minnie,

Let's not be histrionic. Lewis Carroll was a monogamous pedophile, Flannery O'Connor was a devout Catholic and Ayn Rand claimed to be human. Even beloved children’s entertainer Ernest Hemingway believed that women have more holes for plugging than spiders have eyes, an old-fashioned but tenacious belief that has been empirically proven untrue without the aid of a high-powered drill.

My point is, if you start eliminating books, ideas, and people whose views make you uncomfortable, what's left? Whale sounds, cottage cheese, and more corpses than a bullfighting birthday party, that’s what.

Sure, Tintin is racist. It's certainly not the most racist thing to come out of 20th century entertainment, and even as it makes contemporary, less racist (fingers crossed) audiences uncomfortable, it's an important historical marker of the sentiment of the times. Ignoring our racist history doesn't erase racism, so feel free to keep cringing your way through Tintin in the Congo. And if you want to assuage your (presumably) white guilt, try tithing to a nonprofit group geared towards battling entrenched racism, groups like Dream Defenders or Black Youth Project 100.

Kisses,

Cienna

The author of To Kill a Mockingbird — and, so far as I'm concerned, the author of only To Kill a Mockingbird — has died at age 89.

Those who believe the Great American Novel is a singular experience have it wrong; there are many Great American Novels, each a timeless snapshot of a particular moment in American history. Of that tradition of Great American Novels, To Kill a Mockingbird is one of the very best, because it delivered the America that we all — Northern or Southern, black or white, woman or man — aspire to create. In one book, Harper Lee gave us the possibility and the promise of America. We could never possibly begin repay her for that tremendous achievement.

Portrait Gallery returns in two weeks

Christine Marie Larsen is off for the next few weeks, no doubt hand-assembling brushes from rarified animal hairs, gathering pigment from the mineraled rocks atop the highest peaks, and making paper from the miraculous cotton rags used to clean the paintings of the old masters in the Louvre.

In her absence, you can always see her work in our archive of the Portrait Gallery. She'll see you all in a few weeks.

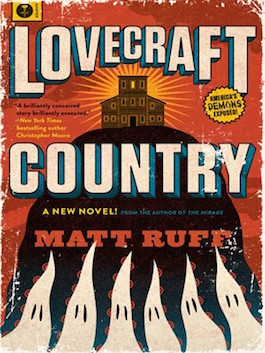

Talking with Matt Ruff about science fiction's racist past

Seattle author Matt Ruff’s new novel Lovecraft Country is a thoughtful, rewarding examination of the connection between genre and American racism. Specifically, it’s a story that juxtaposes America’s shameful history of systemic racism with the racist history of American science fiction. While the former is well-documented, sci-fi’s racist past is much less overt.

The pivot-point for the novel is arguably the most famous racist in American literary history: HP Lovecraft, the cult horror writer who was an unabashed white supremacist. Lovecraft Country holds Lovecraft accountable for his beliefs. By centering the book on the family of an African-American man named Atticus Turner, Ruff is handing Lovecraft’s legacy off to a new protagonist, one who Lovecraft, by all accounts, would have loathed. The resulting narrative is fascinating, illuminating, and surprisingly fun.

On Tuesday of this week, I interviewed Ruff as part of his book release party at Elliott Bay Book Company. We discussed the book’s origins — it began as a pitch for a TV series — and the idea of Lovecraft Country as a secret history of science fiction’s racist roots. With Lovecraft Country, Ruff is thoughtfully rejecting that tradition, and trying to build something new.

I really enjoyed this book. I've enjoyed every book that you've written, but this one is really something special, so thank you for writing it.

Well, thank you.

First I just want you to start by telling us your history with H.P. Lovecraft as a reader.

I first read them when I was younger, and Lovecraft initially for me was one of those writers where I actually think I liked his imitators better than him. He's known for using very archaic and ornate language, and he does tend to go on sometimes. I think when I was young I liked the spirit of Lovecraft more than the reality of Lovecraft.

Then as I got older I tried him again. There are still some of his stories that don't work for me, but when he works, he really does work. I really like At the Mountains of Madness and The Shadow Over Innsmouth and The Call of Cthulhu.

He gives good dread. One of the characteristics of a typical Lovecraft story is that the monster either doesn't show up at all or only shows up in the last paragraph. It's all about being in a place where you don't belong and you are seeing all of these signs and portents of doom — there are people or monsters who mean you ill, and at some point they're going to come out and get you.

Obviously, one way to read the Cthulhu mythos is as a parable or an allegory for Lovecraft's white supremacist belief system. The Cthulhu mythos is all about how once upon a time aliens from beyond space ruled the planet. They went into decline and either retreated back beyond the stars or into the deep ocean. Now humanity is having its day in the sun, but someday when the stars are right the aliens are going to come back and wipe us all out.

Lovecraft believed that what he called Teutonic Aryans were the pinnacle of human cultural evolution, but that was a temporary situation. Eventually some other group, maybe the Chinese, maybe the Japanese, were going to come and take over. They would have their turn until some other race knocked them off, and eventually all life on earth would die and the uncaring universe would go on without us.

One way to read the Cthulhu mythos is this fictionalized version of the fragility of white supremacy, and Lovecraft's fears about that, and his need to be on guard against miscegenation and race mixing and democracy and liberal ideas about all people being created equal. What's interesting about it is in part because white supremacy generates legitimate fear of other people. If the Klan's coming for you, you're going to be just as scared as the Klan maybe is about the fall of white supremacy. The stories work both ways. You don't have to share his belief system to understand what it's like to stop at a town overnight and suddenly find yourself a target of a lynch mob. It's interesting stuff.

You must have been pretty close to the end of the process with this book when the controversy over the World Fantasy Award happened.

Yeah.

For those of you who don't know, there was a controversy over the fact that the World Fantasy Award was a bust of H.P. Lovecraft.

Has been for 40 years or something.

Yeah, and so they finally changed it. It's no longer H.P. Lovecraft's face. Were you paying attention to all that when it happened? It's certainly brought him to the forefront of the sci-fi community again.

Yeah, I heard about it. I have the internet.

I wasn't sure what your writing process was.

I follow these things. I've learned from experience not to comment on them generally when they're going on because there's just no good to be had there. [The anger over Lovecraft] makes perfect sense. The science fiction/fantasy world right now is undergoing this cultural upheaval as, very belatedly, people of color and women are demanding their place in the sun, demanding more stories featuring them as characters. This created a PR problem for the face of World Fantasy being a guy who compared black people to farm animals.

It was Nnedi Okorafor, who had won a World Fantasy Award and wrote a blog post saying she was just appalled to have won this honor where she got to have H.P. Lovecraft's head in her house, looking at her. It made sense that, yes, they would get rid of that, but of course it's a controversy because for a lot of people, they like artists for what they like and ignore the parts of them they don't care about. I think there are a lot of people that just felt like, “well, yes, he's got these horrible views, but I just like the stories. Why are you bringing these politics into it?” It became a controversy, but it's a no-brainer.

In many ways, to me, it feels like the title Lovecraft Country is almost a feint because this book is interested in all sorts of sci-fi. In the piece you just read, Ray Bradbury is mentioned multiple times. H.G. Wells is name-checked, L. Ron Hubbard. There's a story that's a riff on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Mort Weisenger-era Superman, and things like that. This book, to me, feels sort of steeped in science fiction history. To me, it feels almost like you're providing an alternate history of science fiction. I was wondering if you would agree or disagree with that reading.

Part of what I wanted to do was take stories that Atticus might have enjoyed reading, but that would never feature people of color as protagonists, and give them a chance to star in those stories. It would be a case of being careful of what you wish for because, of course, these aren't necessarily fun stories to find yourself a part of.

It was typically the idea that each character in the story would have their own mini-adventure, their own weird tale. I would start by taking a classic story — like, somebody buys a haunted house or somebody finds themselves being chased by an animated doll. First of all, how does this happen to my protagonist and how does having a black protagonist change the nature of the story?

For example, in the haunted house story, Atticus has a friend named Letitia who comes into some money and decides she wants to buy a house in a white neighborhood, because she wants a nice house and that's what you have to do is get a house in a white neighborhood. She gets a surprisingly good deal, and of course it's because the house is haunted. The ghost is white too and doesn't want her there any more than the neighbors do, so she's got to find a way to play the dead off against the living. In some ways, it's taking a story that's been told many times but putting this new twist on it, and at the same time giving you a chance to talk about the real life difficulties of what it would entail to try and just buy a decent house with the money you have at the time. That was definitely part of the process — to tell stories that might have existed had the country been more open, had history been different. These are the kinds of stories that might have existed back then.

That partially answers my next question — about whether it was necessary to structure the book as a novel in stories. Because you do have all these perspectives in the book, and each one is a different riff on different sci-fi themes. Did you ever try to break it out into a single novel or did it always come to you in this episodic format?

This was actually one of the reasons it took me as long as it did to write the book, because with [my most recent novel, also based on a TV pitch] The Mirage, what I was able to do was take this idea for a TV show I'd had — I’d come up with three seasons' worth of subplots — and I could just strip out all of the side stuff and focus on the central mystery of the story. That gave me a story very much like that of a traditional novel.

But in Lovecraft Country, part of the point of the story was to allow these characters to star in their own weird tales. I wanted to spend more time on the character development as well. In television terms, the monster-of-the-week episodes were as integral to the concept as the mythology episodes. That suggested a novel in stories, which is not a phrase that publishers, and I think maybe readers, are necessarily enthusiastic about.

For awhile I was like, “yeah, do I really want to do that?” Then at the end of 2010 I found myself in my then-editor's office. He was saying “The Mirage is coming out. Do you know what you want to write next?” I'm like, "Well, yeah, I've got this idea, but it's a novel in stories, so I don't know." At that point I really knew: yeah, that is what I'm doing. If I'm still thinking about this, I've got to figure out a way to do it.

What I ended up doing was stealing a different metaphor from Netflix — this idea that yes, reading the book would be like binge-watching a full season of TV. It would be episodic, but each chapter would begin with a cold open, a cool bit of business that would grab the reader's attention right away, even if you didn't get necessarily how this fit into everything else you'd been reading.

Then as the monster-of-the-week thing unfolded, eventually the connections would click into place. Now we've got another piece of the mythology as well. You would get to know each of these individuals, because I wanted to spend time with the characters. Then, when you were done you would have this family who you knew, and you would have this complete story about the mystery of Ardham Village and the... I won't spoil it. You would have this complete epic story that had been told in episodes.

That was how I had to do it. I think it works. We spent a lot of time in the editing [process] smoothing the transitions and just making sure that it felt less like separate short stories and more like pieces of a puzzle that you could see how they fit together as you were going along. Hopefully that comes through.

Well, also, the history of science fiction did tend to lean more toward short stories more than other forms. Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles was short stories.

Yeah, the Martian Chronicles are built up of short stories. Exactly.

It’s interesting to me that you are so open about talking about TV and your ideas coming from TV and mimicking the story structure of Netflix, which I think is something that a lot of novelists should start thinking about, because it is a different form. The new TV model is adopted from novels, and so novels need to respond to that. I also think that had you started your career ten years later, you could very well be working for Netflix now, because when you pitched the idea that became Lovecraft Country, that was back when there were three series that were doing this intensive narrative work, but now they're all over the place.

Yeah, and I think that, part of it, the idea caught up with the time enough that it can work now. Certainly that affects how people receive the book too, so maybe it will make it easier to get into it than if I'd written this in 1990 or something.

There are obviously a lot of potential pitfalls for this kind of a book as a white man writing about the African-American experience. The cultural lens has fallen more onto representation, and also, as you said earlier, letting people speak for themselves. I was wondering if you could share your process in writing about these topics? Because it's tricky business. I think most people would agree that white people should not just write about white people, but there are a lot of places where something like this could have gone wrong.

But it's good to be a little nervous. It keeps you awake. My novels are all over the place. Those of you who have read them, they're all over the place in terms of subject matter. I like using fiction to see and experience other people's worldviews and see how other people think and cope with problems. They may have the same temperament as me and some of the same interests, but they have a whole different set of challenges. I find that really interesting and fascinating. I don't know, I seem to have a knack for it.

The process always starts the same way. I work up a history for the character I'm working on. I think about what has their life been life up to this point. What do they want? What do they do? How did they get here? The goal is to work up a psychological model that lets me intuit how they would react in different situations, and I can tell when it's working, when it feels psychologically realistic. The other thing, too, is when you talk about the black experience — there's not one, there's a different one at least for every African-American. That's just the real people. Then you get into fictional characters and that you can have dozens of, or millions of, different possible experiences.

I'm not trying to make a grand statement of how everybody lives. I want to have a set of individuals and who feel like real people and who come at things in a different way and are interesting to write about. If it's an ensemble piece like [Lovecraft Country], how are the characters going to view each other, and how does one person's view of why he's doing something match somebody else's?

I have enough that I can start writing and feel comfortable in knowing how they'll behave and how they'll talk. Then that gets refined as I go along. Typically what will happen is I'll come to a point in the story where I need a character to do something for plot-related reasons, and so I know why I want them to do something, but I haven't figured out why they would do it.

This is an issue. In particular this comes up a lot in horror, where you frequently need to have characters do things that are just stupid. “I'm going to go check out that noise in the basement. The batteries in my flashlight are dying, so I don't think I'll turn it on until I'm in the really dark part of the basement.”

In some ways it was easier with this background because people who are oppressed don't have a lot of options. In a lot of cases in Lovecraft Country, the answer to why are they doing this crazy thing is because this is the only chance they have to get the thing they want. Even if the game is rigged and they know they're probably not going to get it anyways, you either try or you just give up in despair, so they're going to try.

In some ways it just made it easier sometimes to answer the question, but I love that feeling of figuring people out and making sense of other people's behavior. It just helps me understand the world better. Yes, the track record for white folks writing about people of color is not stellar, but I think a lot of the explanation for that is not you can't do it. It's just that a lot of folks don't care to. They aren't interested. They either haven't found a reason to be interested or they just aren't interested. It's when you treat it as a chore or something — “well, I don't really want to do that, but I guess I've got to put a black character in there” — that you could do bad, lazy work. People reach for clichés when that happens. But I really wanted to write this book and I wanted to get to know these characters. That makes it much easier to do a good job. That's the answer, I guess.

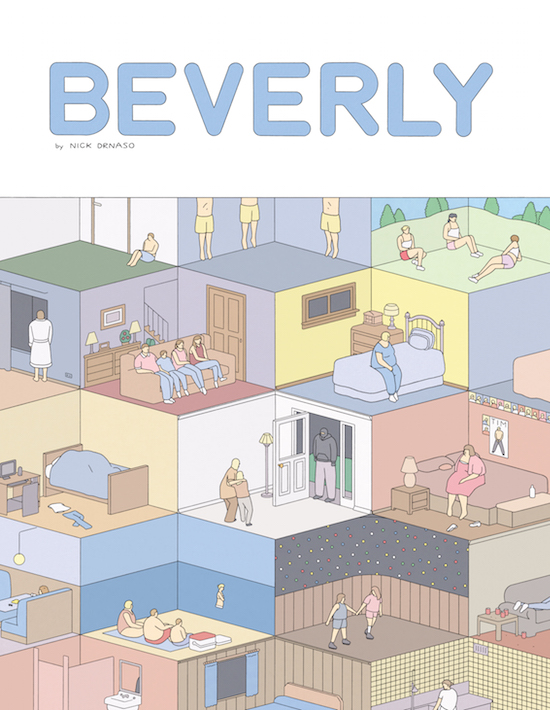

Thursday Comics Hangover: The masterful banality of Beverly

If you were to ask me to nominate one cartoonist to create a comic book adaptation of a Todd Solondz film, I would, without a second thought, choose Nick Drnaso. Like Solondz's films, the world in Drnaso’s new collection Beverly is ugly and mundane; unattractive Americans live their boring lives in bland surroundings — cut-rate hotel rooms, tract housing. Drnaso draws his figures with simple lines, often at the middle distance. He rarely employs close-ups; his characters lack detail or much by the way of physical nuance. It’s a kind of bland suburban hell.

If you were to ask me to nominate one cartoonist to create a comic book adaptation of a Todd Solondz film, I would, without a second thought, choose Nick Drnaso. Like Solondz's films, the world in Drnaso’s new collection Beverly is ugly and mundane; unattractive Americans live their boring lives in bland surroundings — cut-rate hotel rooms, tract housing. Drnaso draws his figures with simple lines, often at the middle distance. He rarely employs close-ups; his characters lack detail or much by the way of physical nuance. It’s a kind of bland suburban hell.

Put simply, Drnaso tells the stories of creeps. A young boy embarrasses himself in spectacular, sexual fashion on a family vacation. A lonely man gets a massage. A young woman reports a horrible crime that puts the community on edge, though the details start to fall apart on closer investigation. You wouldn’t want to spend any time with the people in Beverly. At best, they’re bumbling and a little bit slow. At worst, you’d move away from them if they tried to sit next to you on the bus.

And yet, Drnaso is a masterful storyteller. With great economy and supreme confidence, he constructs whole worlds — worlds of mundanity, filled in with rainbows of beige — and he populates them with people who don’t experience desires so much as vague fumbling in the general direction of happiness. The most innocuous protagonist is a mother who is excited to take part in a television market research survey; it’s such a small want that when it collapses in disappointment, the sadness somehow feels even more profound.

Beverly will make its readers uncomfortable. That must be part of Drnaso’s plan. Rather than skip through the awkward sitcom the aforementioned woman is excited to watch as part of her marketing survey, Drnaso lays the whole TV show out in tiny panels, and it’s just as bad as the most mediocre TV show you’ve ever watched. ”Sorry for the way I acted earlier,” the bland father says to his bland wife as they get into bed at the end of the show. “You and the kids are too good to me.” His wife replies, “Oh, honey, you’re too good to us!” Turns out, you can make a comic that’s just as awkward as bad network television. All it takes is a whole lot of talent and a ferocious willingness to maintain a chilly distance between you and your readers. Like the worst television, you can’t look away from Beverly — you’re hypnotized by all the horrible beauty.

We here at the Seattle Review of Books are incredibly excited for Link Light Rail to open to Capitol Hill and the University District. (Fun fact: light rail opens on the exact same weekend as the APRIL Festival's big book fair at the Hugo House! That's your Sunday, March 20th all sorted for you.) And this video from Sound Transit profiling Seattle cartoonist Ellen Forney is only getting us more excited about launch-day, especially because it's got plenty of footage of the installation of Forney's beautiful illustrations of giant hands in the Capitol Hill station.

This is big news: independent comics publisher Image Comics — home of some of the best ongoing comics series in America today including Saga, The Walking Dead, and Bitch Planet — just announced that they're going to host Image Expo, their new-title showcase, at Emerald City Comicon this year. This is the first time they've partnered with a pre-existing convention for the Expo, and it's also the first time the Expo will take place in Seattle. Bleeding Cool reports:

They’ve allied themselves with ReedPOP to be part of the Emerald City Comicon this year in Seattle on Wednesday, April 6th, from 10 am to 6 pm at the Showbox Market theater... They’ve already announced Leila del Duca, Joe Harris, Rick Remender, Alison Sampson and Jonathan Hickman with more to come and they always have surprises they roll out on the day.

This is a significant nerd coup for Seattle. And it's followed by a spring formal dance, apparently, which sounds kinda incredible. Tickets are available now.

Across the transverse

Published February 17, 2016, at 12:00pm

Juliet Jacques documented her transition from male to female in a Guardian column, collected and expanded into a recent memoir. What does she have to tell us, in the modern day, about that transition?

University Book Store's Caitlin will predict your reading future

The thing you realize within a few seconds of talking to University Book Store’s Caitlin is that she reads a lot. Like, a lot. She estimates she plows through about five books a week, on average. “I read fast,” she admits. “Partly because when I was in college, I would do theater, and I would also have to read James Fenimore Cooper or Moby Dick” for class assignments. Every time I see Caitlin, she’s gushing about some book that just came out, or that is about to come out, or that will be out in a month or two. Few booksellers in the city are as capable at forecasting the near-future of books as she is; talking to her is a window into your immediate reading future.

Caitlin has been a bookseller since 1994, when she started at a branch of Media Play, a short-lived attempt at a multimedia chain store concept by Sam Goody that she describes as “their answer to Barnes & Noble and Borders.” When I admit that I’ve never heard of Media Play before, Caitlin says that’s not unusual: “they opened a lot of locations really fast and probably too close to each other,” and the chain burned out in a matter of years.

Caitlin had just graduated college with a degree in literature, so she had hoped for a position in the fiction section, but she was assigned to the children’s section. She didn’t know much about kid’s books, but she accepted the challenge gracefully: “I just read the Newbery Award winners and some of the old Newbery winners and the Goosebumps books and dove right in.”

About a year and a half ago, Caitlin became a buyer for the bookstore. She meets with publisher sales representatives and evaluates the prospects of upcoming titles — she’s already buying for summer and fall of this year. Basically, based on sample chapters, sales copy, and advance reader copies, she tries to predict what customers will want to read three to six months from now. A lot of the selection process, she says is based on “a hunch,” though if an upcoming title is “something I love or a coworker loves, it gives me a better feeling for the book.”

Caitlin has worked longer at University Book Store than at any of her other bookselling jobs, in part because it’s “a great place to work. It’s a store that really, really cares about its employees,” which means that “a lot of the employees have been there for a long time,” which in turns creates a sense of continuity that most bookstores can’t replicate. But when you get down to it, she says, “I feel lucky to be surrounded by books. I grew up surrounded by books. I work surrounded by books, and I work with people who love books.” She makes it sound like paradise.

Still More Book News Roundup: It's a busy day!

After a long weekend, we're left with too much news for one single Book News Roundup to contain!

Capitol Hill Seattle Blog has the skinny on V2, the new temporary arts space in the old Value Village building on Capitol Hill's 11th Ave. Literary tenants include Bumbershoot producer One Reel and possibly Hugo House, and the space will be broken up into "performance areas, rental studios, classrooms, offices, and storage."

Starting on March 6th, the Henry Art Gallery will be free on Sundays. Don't think this is book-related? Piffle, I say! A few years back, the Henry hosted a brilliant exhibit about the history of indpendent publishing, including a few early e-books and some very interesting publishing projects. They also host author events and publish four or five books a year.

"I was literally 30 minutes from saving the company," former Borders CEO Mike Edwards says in Paula Gardener's story about the death of the once-popular national bookselling chain. If this story makes you too nostalgic for Borders, please go read my account of what it was like to work at Borders, which will hopefully remind you that the chain had a lot of big problems that led to its eventual collapse.

Book News Roundup: A celebration of Arabic poetry, a chance to get your chapbook published, and more

Two Sylvias Press's annual chapbook contest is now open for submissions. The reading fee is $15, but the payoff is pretty great: the winner gets $400 and 20 copies of their finished chapbook. A poem by the winner of 2014's chapbook contest, Cecilia Woloch, was recently featured in the New York Times Magazine.

We've already suggested two great events for tonight, but we just learned about this event happening in the Husky Union Building on the UW campus tonight, and we wanted you to know about it: an evening of Arabic Poetry and Music, featuring poetry read in English and in Arabic by students. Some Seattle-area publications want you to think that Seattle isn't an international city of literature; that's just not true. This reading is just one great example of how Seattle's literary scene represents the whole world on a regular basis.

At the Comics Reporter, Dan Clowes has written a remembrance of Alvin Buenaventura, a prominent comics editor and publisher who passed away last week. Clowes writes, "he was inexplicable, the most singular human being I've ever met. There's nobody else in the world even remotely like him."

Over at The Intercept, Masha Gessen has written about the sad state of self-censorship in the Russian publishing industry.

If you're an artist in need some inspiration, here's Seattle cartoonist/Short Run co-founder Kelly Froh's wonderful appearance on the Seattle Channel show Art Zone with Nancy Guppy.

Panic Blossom

[to be read very quickly, as if almost out of breath]

Panic blossom speaks passwords into the edge of the voice at the edge of the speech that listens.

The password for membrane is not squirrels. It is also not squirrels of intestinal magic. It is not

squirrels that ride the antlers of your skin.

Every sink will be shallow and the deer with eight legs will run faster but on a treadmill of paper.

There is a password for the membrane. To get out is different from to get in.

The password is glass

The password is glass in a volcano

The password is clear glass

The glass is cloth

The glass is a cloth of waterfalls

The waterfalls are not the password

The password is not glassSquirrels are not the password but they carry the keys. They carry the keys that wilt in the locks. They are leaf keys and they are not passwords.

A squirrel in our story has fallen into a pond.

The water and the squirrel fight their failing.

The water taps the lungs. The ghost leaves a lotus.

I didn’t know the password. The password was not squirrels.

There was a key but it was waterfalls.

Let’s talk about something else.

I barely knew them, but they kissed me everywhere, the squirrels.

It wracked my nerves but gave me purchase

for the password. Here and there a leaf fell down my shirt.

The leaves that cannot open things panic in the lock.The hinge hears the blossom panic in the door.

That is the key.

The sinks are shallow so no one will drown.

The deer is catching up.

Its eight legs in the corner are listening to the edge. At the edge is a boy under glass

who looks through sheets of water.

It went around, it came around

In his introduction to the Hugo House’s Lit Series event on Friday night, event programmer Peter Mountford called “what goes around comes around” the “immaculate conception of clichés.” Most clichés, he said, have very clear, recognizable origins, but “what goes around comes around” has existed for as long as language has existed, and it can’t be broken down into any simpler parts. It’s one of the clearest, simplest concepts that exists in written language.

Which makes sense. Repetition holds a strange power for humans. We use repetition to calm ourselves and others, but repetition can also be incredibly annoying. Artists will use repetition as an artistic device, by mirroring an event at the beginning and end of a piece of art to demonstrate a change in the audience’s perception. Critics like to repeat an artists’ words back to the artist, as a refutation or a bolstering of a point. One of the easiest ways to get a laugh is to bring down an arrogant character with their own words or actions. Just about everyone on earth, regardless of their religion has a basic understanding of what karma is.

So the four artists the Hugo House asked to respond to the cliche — Seattle poet Sierra Nelson, author Heidi Julavits, Seattle musician OC Notes, and celebrated poet D.A. Powell — were dealing with elemental stuff. The pleasure of the Hugo House’s Lit Series is watching how many different ways the theme can be interpreted. But there was a risk with this particular assignment: the simplicity of “what goes around comes around” could also be a problem with creative interpretations of it — if this idea seems hard-wired into our brains, maybe that understanding might resist deeper explanation?

OC Notes recognized from the stage that he and Nelson demonstrated a similar understanding of the theme, in particular with reference to karma. Nelson started the night reading a list of words and phrases relating to the theme — dirty dishes, hangovers, ouroboroses — and the audience arrived to discover that every seat in the house had an index card with one of the phrases written on it. (Mine was “Diet Crazes.”) She encouraged people to introduce themselves to each other as the concept written on their card, creating a moment where the poem came alive.

Nelson’s greatest strength is in her scientific approach to poetry, her willingness to throw poems against a thesis in an effort to create a crack where meaning can get inside. She unveiled a number of repetition-based poems — pantoums, blues lyrics — to bring the theme into the form, as well as the spirit, of her work. Along the way, she unveiled several gorgeous little observations, about Star Trek: The Next Generation, and Justin Timberlake, and the stunning revelation that Aplets and Cotlets are the flavor of grief. OC Notes shared Nelson’s spirit of investigation, crossing musical genres and demonstrating a playfulness in his three songs created just for the evening. The last song, a blues-based declaration that “Karma’s calling on the line/won’t you please pick up the phone?” captured perfectly the dread of actions coming back to haunt a person.

Powell was less successful. His interpretation of the theme materialized as a batch of new poems written in the spirit Powell brought to his poetry when he first started writing as a teenager. This kind of neo-juvenilia was occasionally funny, but Powell stuck with the theme way too long, reading what felt like dozens of poems, many of which had titles like “That Pussy Is Tight” and “Fuck Buddy.” At five minutes, it would have been a hilarious interlude. At near twenty minutes, it was interminable.

Julavits addressed the theme with an essay — possibly one that might expand into a book, she mused from the podium — about the possibility that one day her young son might rape a woman; every rapist has a mother, after all. Julavits reflected on her son's infancy, when he screamed and cried and demanded her body with the bone-deep understanding that he might die if she withheld her body from him. She called her father “a total non-rapist,” but suggested that, basically, she didn’t understand how to raise someone who would not rape. While all the other artists responded to the theme with a florid spray of playful work, Julavits dug deep inside, questing around parenthood and free will and destiny and consent. Without the density of her inquiry, the night might have felt a little too light. With her essay, everything came back around to making sense again.

The art that comes from restriction

Our thanks to Sagging Meniscus Press for sponsoring the site this week with a truly unique, and remarkable, book: The Too-Brief Chronicle of Judah Lowe, by Christopher Carter Sanderson. On our sponsors page we have three excerpts: from the introduction, which sets the stage, and from each of the two sections of the book, each told through the lens of severe restriction. All art comes from the artist creating rules and restrictions — some of them mundane, such as the choice of paint or the size of canvas, some of them severe (those of you who saw the brilliant film The Five Obstructions will know what we're talking about). Certain artists work within severe restriction, and the work, like it does here, can end up bulging at the seams. You really have to read this.

Sagging Meniscus took advantage of our sponsorship program — new dates are now available through the Summer. If you're a small publisher, writer, poet, or foundation that is looking to back our work, and advertise your own in an inexpensive and expressive way, take a look at our open dates. We'd love to talk to you about the possibilities.

Caught after dark in Lovecraft Country

Published February 15, 2016, at 12:00pm

Matt Ruff's new book Lovecraft Country turns old H.P.'s racism on its head. It's an ambitious work, attempting to use genre to undermine America's racism against African American people. Was he able to pull it off?

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from February 15th - 21st

MONDAY Start your week in readings at Third Place Books up in Lake Forest Park. Debbie Clarke Moderow reads from her new book Fast into the Night: A Woman, Her Dogs, and Their Journey North on the Iditarod Trail. If you’ve ever wondered about sled dogs — and c’mon, pretty much everybody has wondered about sled dogs — this is a good chance to learn.

And so our ALTERNATE TUESDAY event is the February Literary Mixer at The Hideout. I went to the last Literary Mixer and had a lot of fun. Here’s the deal: bring the book you’re reading. Buy a drink. Talk to people about the books they brought and be prepared to talk about the book you brought. That’s it! (You might want to bring a piece of paper and a pen so you can write down some book recommendations, too.)

WEDNESDAY Tonight, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore reads at The Furnace Reading Series at Hollow Earth Radio. The Furnace is a reading series in which one writer reads their short story with audio accompaniment — music, sound effects, etc. When Sycamore moved to Seattle from San Francisco a few years back, she became a cornerstone of the literary community almost overnight. Her memoir The End of San Francisco is about gentrification and sexuality and what it’s like to watch a city die. That’s going to be a big part of her reading tonight, apparently: press notes say she’ll be reading from an “elliptical essay [that] ruminates on the complexities of desire and belonging in a shifting community.”

THURSDAY It’s a book party to celebrate the release of Alexander Chee’s The Queen of the Night at Hugo House. Queen, Chee’s second novel, is about an opera singer who is cast in a production that is adapted from her own life story. This is a big, buzzy book that everyone is talking about. After the reading, incredible Elliott Bay Book Company bookseller Karen Maeda Allman will lead a Q&A.

SATURDAY Did somebody say "conflict of interest?" Paul Constant will be giving a lecture and hosting a conversation about book-to-film adaptation at the Northgate Barnes & Noble at 1 pm this afternoon. This event is part of a book fair to benefit the good people at Scarecrow Video, which is the greatest damn video store in the entire United States of America. Come out and show them the love.

And your ALTERNATE SATURDAY event is the Bwitch Zine Release Party at Push/Pull. This is a thematic anthology zine — this edition’s theme is “dark fairytale” — that is “for all the girls in the comic scene that want to be heard and express themselves.” This event offers free snacks and drinks, as well as some sort of a musical act, which has not been announced yet.

SUNDAY The Monorail Reading Series happens tonight at the Fred Wildlife Refuge. Tonight’s readers are Lisa Ciccarello, Willie Fitzgerald, and Feliz Lucia Molina. Ciccarello is a poet who has published one collection and eight chapbooks. Molina is the author of two books, with a chapbook and another book on the way. Fitzgerald has published fiction and non-fiction in a bunch of places, including right here at the Seattle Review of Books. A boozy-fun reading from a bunch of up-and-comers seems like a great way to cap out the week.

Sunday Post for February 14, 2016

Samuel R. Delany Speaks

Wonderful interview with the one and only Samuel R. Delany, by Cecilia D'Anastasio.

When he was 11, Samuel R. Delany stayed overnight at a Harlem hospital for observation. It was 1953, and nearly a decade before Delany would publish his first science-fiction novel. He had already realized he was gay. With trepidation, he asked the doctor, a white man, how many gays existed in America. The doctor laughed. “[He] told me it was an extremely rare disease,” Delany says. “No more than one out of 5,000 men carried it.” Rest assured, the doctor added, no medical records existed confirming the existence of black homosexuals. “Simply because I was black,” Delany says, “I didn’t need to worry!”

How Valley of the Dolls went from a reject to a 30-million best-seller

Self promotion was Jacqui Susann's game, and she was so good at it, that she started a viral movement without that crutch, the internet, that we all rely on now. Martin Chilton writes it for the Telegraph.

Her novel Valley of the Dolls was dismissed as "painfully dull, inept, clumsy, undisciplined, rambling and thoroughly amateurish". So how did such a poor book go on to be registered in The Guinness Book of World Records in the late Sixties as the world's most popular novel? The success of Valley of the Dolls – to date more than 30 million copies have been sold worldwide – is a tale of one of the most tenacious and sharp-eyed publishing campaigns of all time.

Liquid Assets

In drought, with water as a diminishing resource, controlling a very limited resource becomes a playground for people who like to make a lot of money. Abraham Lustgarten, in a very long and detailed piece for ProPublica, looks at Wall Street's interest in Western water rights.

Deane is not a rancher or a farmer; he’s a hedge-fund manager who had flown in from New York City the previous night. And as he appraised the property, he was less interested in its crop or cattle potential than in a different source of wealth: the water running through its streams and coursing beneath its surface. This tract would come with the rights to large amounts of water from the region’s only major river, the Humboldt. Some of those rights were issued more than 150 years ago, which means they outrank almost all others in the state. Even if drought continues to force ranches and farms elsewhere in Nevada to cut back, the Diamond S will almost certainly get its fill.