Whatcha Reading, Kamari Bright?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Kamari Bright is a poet, filmmaker, artist, and musician, who also happened to be our Poet in Residence for July. See the five poems we published: Chalice, And the Moon, Nephilim, The Garden, Eve, and our interview. She'll be appearing at the 3rd Seattle Urban Book Expo, on August 25th.

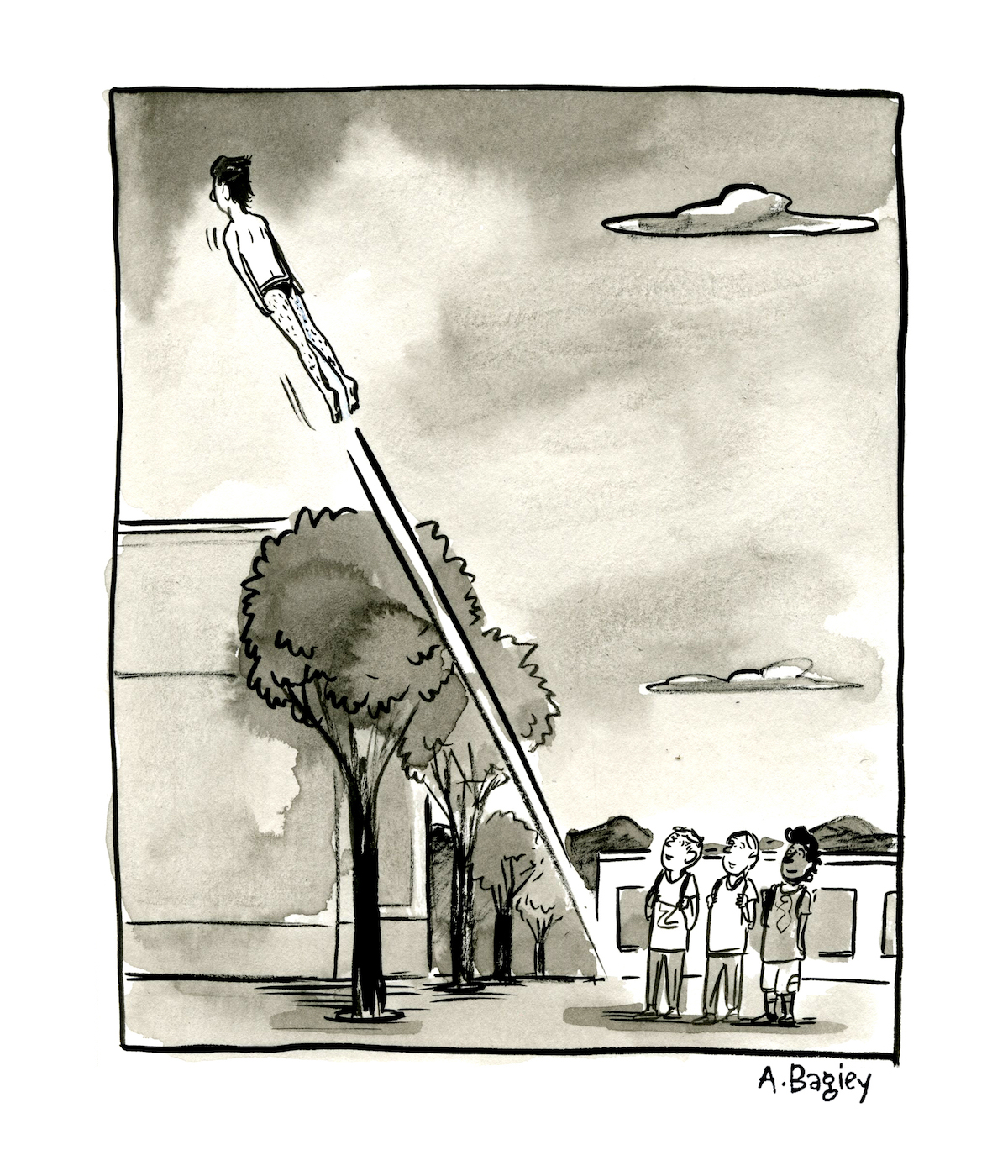

What are you reading now?

Rock | Salt | Stone by Rosamond S King

What did you read last?

I Think I'm Ready to See Frank Ocean by Shayla Lawson

What are you reading next?

(Hopefully) Barracoon by Zora Neale Hurston

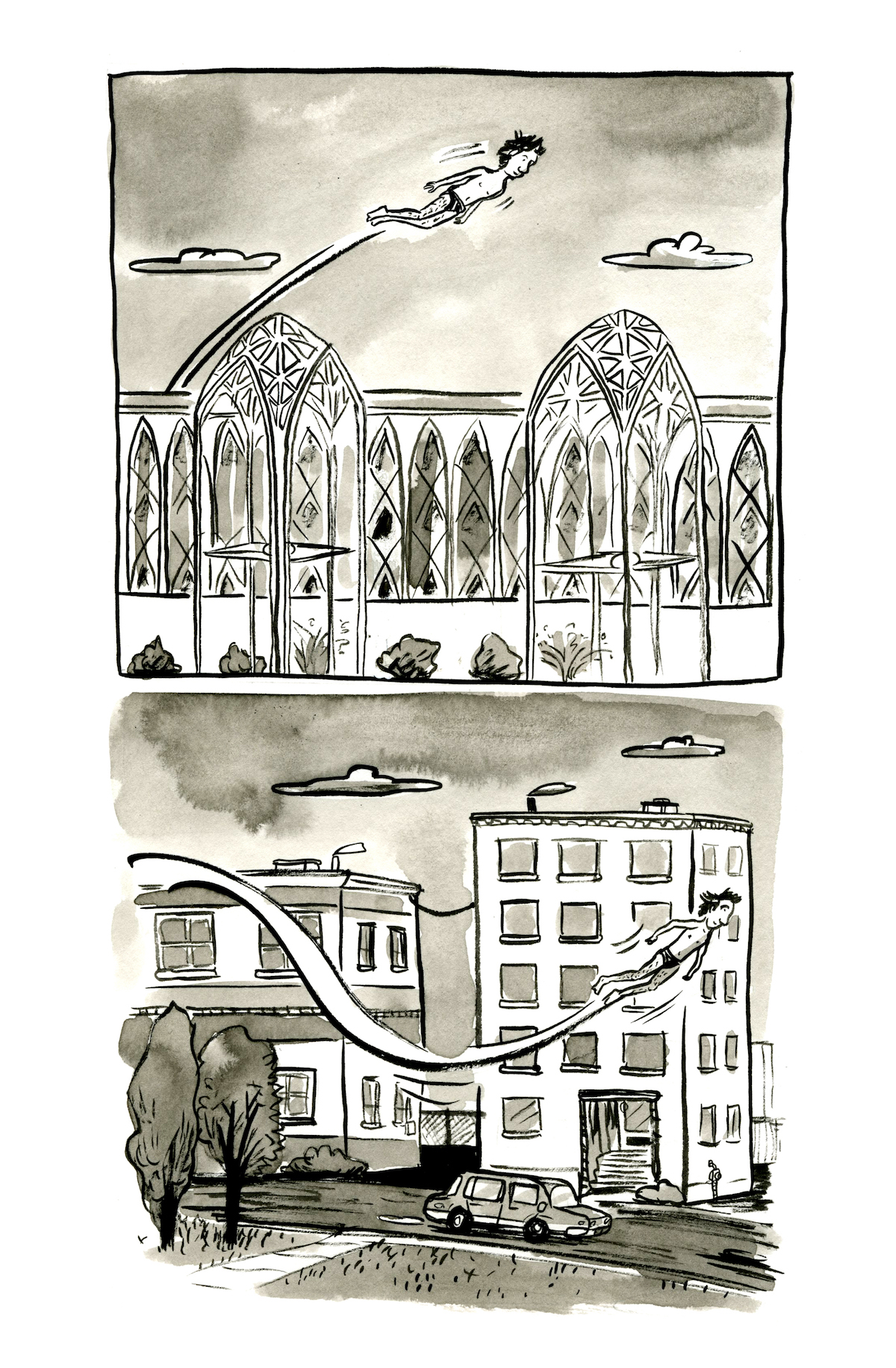

July's Post-it Notes from Instagram

Over on our Instagram page, we're posting a weekly installation from Clare Johnson's Post-it Note Project, a long running daily project. Here's her wrap-up and statement from July's posts.

July's Theme: Last July

Every summer I think I’ll get a million things done, catch up on every longterm personal and professional goal... then end up sick for weeks, or totally useless and unfocused because apparently not taking weekends off from work ever suddenly catches up with you, who am I to think I can outrun that. Or I’m frantically applying to the million art things with July deadlines, or I’m languishing in the heat, confused about why I don’t function better in it. I mean... do I have to say more about the last post-it? Housework in hot weather—I’m maybe not the best at it. Really, not even in the “A for effort” category... it’s more like, WHAT ARE YOU DOING CLARE. WHY ARE YOU VACUUMING YOUR FEET IN YOUR UNDERWEAR. All I can say is it seemed logical—inevitable even—at the time. Also fireworks. I know fireworks displays are indefensible, profoundly problematic in countless ways, and yet in my private heart I remain deeply intrigued. Back in the US after years away, I kept grasping for that one viewpoint where they look as crazily big as I remembered. But it might just be the past. Last July, with the larger world falling to pieces the way it’s always doing now, I found myself in a shockingly charmed moment personally. I’d just been awarded a glamorously unrestricted grant, been handed the actual check on Pride Sunday just as June ended, in the quiet, dark, blisteringly hot afternoon rooms of a fancy club called the Ruins. Sharing the news on social media felt like I was someone else. I was looking forward to my first residencies ever, and this beloved literary review (yes, this one) wanted to start publishing my Post-it Note Project each week. This July I’m just my old self, recovering from a bug, floundering in a relentless sea of applications and rejections, still worrying about small things, or the world, or my friend in Turkey, will I make it back there to her, will things get better, when can I just make all the work I dream of making, oh my god I need to vacuum. But I am still grateful for the same things too. The lake is the lake, and one song on the radio will solve everything for that moment. I’d forgotten the name of that song, such a heartbreakingly lovely thought: No Danger.

The Help Desk: Stop my wife before she bathes with a book again

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

My wife and I have a great relationship but she likes baths. She loves to take books into the bath, and they always get wet and waterlogged, she’ll scratch her leg and then instead of drying her wet fingers sensibly on a towel, she’ll just turn the page.

I like buying first editions in hardback. Not like a snooty collector, but to support authors and I can afford them so why not? I just can't stand what she does to my books. It's driving me mad. She ruins them!

I’ve tried getting her a Kindle (she thinks it will electrocute her), buying TWO copies of books she wants to read (she has a crazy good memory and doesn't use bookmarks so it's not uncommon that both books get a soaking), and plain old pleading, but she keeps saying “honey, relax, it’s just a book.”

Yeah. But then see what happens if I leave one of her screwdrivers out of place. Ugh.

Anyway, she agreed that I can write to you and get advice, and she will abide by it. Please, Cienna, for the love of all that is good. Please help me.

Daphne, Belltown

Dear Daphne,

Even your wife must admit that sometimes wonderful things are incompatible. Drinking and texting. Feminists and weddings. Raccoons and dinner parties. (Stop me if I'm repeating myself.) Such is the way with books and bathtubs.

That said, it's nearly impossible to change a person and foolish to try, much like attempting to switch the theme of your aunt's funeral from "farmer's banquet" to "Harry Potter" because the only black thing you own is a cloak with matching hat.

So what do you do? Tell your wife that from now on, whenever she ruins one of your hardcover books, she owes you $100. With that $100, buy yourself a new hardcopy and save the rest until you have enough in ruined book restitution to purchase a lawyer's bookcase – one with a lock in which you can store your prized collection. And if she fails to pay up within a week of each offense, start sponge-bathing her screwdrivers.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Raymond Chandler

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday, August 2: The Annotated Big Sleep Reading

Owen Hill’s latest book is an annotation of Raymond Chandler’s classic detective novel. Paul Constant says: "These annotated guides are a real pleasure to read, particularly in works that have maybe lost some nuance due to the time they were published in. While I haven’t read this particular edition, I suspect that Chandler’s work will feed well into the annotation format."

University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.

Kissing Books: punched by the lowest point

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

In romance circles, there is a thing known as the Black Moment.

Here is how it goes: you have your two protagonists, who we’ll call H1 and H2. For most of the book they have been drawn closer and closer together — maybe they’ve been having sex, maybe they’ve been forced to marry, maybe they’re working together to eradicate space pirates from the newly colonized Argyle Nebula. They’re on the verge of something big, a life-changing realization that they love one another, that they could spend the rest of their lives together, that everything they want is right there in front of them. But first! The author must take all their old fears, all the old problems, all the long-burning fuses of catastrophe that have been set alight over the course of the plot (“And no one will ever find out…”= someone’s definitely gonna find out), throw everything at our lovers, and set their entire world on fire. Maybe H1 learns that H2 was only sleeping with them to win a bet. Maybe H2 learns tht H1 has been captaining the space pirates all along. The specifics vary but the effect is the same: the H1-H2 relationship, once so shiny and promising, shatters.

That is your Black Moment. It is when H1 and H2 believe they’ve ruined everything.

The reader feels all that pain along with them. Because of course we read romance to feel things. A romance is the emotional equivalent of a roller coaster, and the Black Moment is the spot where the train has cranked up to the highest point, and you take one breath, and then you plunge down into the depths at speeds that no human should rightly survive. A good Black Moment lands in the body in an intensely physical way. It is not an intellectual experience, some distant and voyeuristic Goodness, whatever shall they do? A well-crafted Black Moment should feel like you’ve been gut-punched.

And you like it. It’s safe to like it. Because it’s going to be all right in the end.

This is the intellectual part: despite what you feel, despite the pain and the anguish and yes, the rage at seeing someone self-destruct, at seeing two people who care about each other just royally tearing one another’s hearts to shreds, you can be absolutely certain that they will get over this, because if they do not, then the novel has failed.

No matter how many times I see it happen, I always am a little awed. If a romance novel makes you feel that everything’s lost, and you do not feel things are right again at the end, it is considered the book’s fault and not the reader’s. We warn each other against insufficient Black Moments: “He doesn’t grovel enough,” we’ll say, because that’s the most common way a book can fail this test. (There’s a Goodreads list about this, can you believe it? And yes, Kristin Ashley is on it. Twice.)

Building such a subjective experience must be done carefully. H1 can’t say, “Aha! I have been the space pirate captain all along!” and then blast H2’s ship to pieces with a laser cannon while shouting about how terrible all the sex secretly was. The Black Moment is not solely a plot twist. It is not simply about surprising the reader (though while I have you here, plot twists aren’t simply about surprising the reader either, you hacks). To take an example from literature, the Black Moment in Jane Eyre is not the part where Jane learns Rochester’s been hiding a wife in the attic. It’s not even the moment where Jane thinks Rochester has died in the fire that burned Thornfield to the ground. Those are points in the plot. The Black Moment in Jane Eyre is the part where Jane almost agrees to marry St. John Rivers to go work herself usefully but unhappily to death as a colonial missionary. Not just because marrying St. John (a priggish and emotionally abusive megalomaniac) would be The Absolute Worst, but because it is the moment where Jane comes closest to losing the most vital parts of herself. It is the highest crisis, the greatest risk, the profoundest moment of dread for the reader. It encompasses everything that has come before — in fact, it depends on it. Losing Jane only matters if we know who Jane truly is.

The Black Moment is the part that makes the Happily Ever After mean something. The old clichés are sometimes cliché for a reason: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy wins girl back. The losing isn’t something you can lightly skip. The losing glues the other parts together.

Of course, the cultural habit of associating blackness with pain and despair is something we'll need a whole other book to unpack, but use of this term, thankfully, doesn’t seem to be racially loaded.

This month’s books all feature exquisite Black Moments. One of them was so horrifying I honestly nearly put the book down out of self-defense; one of them has a grovel scene that was so outrageous and bold it made me want to laugh and cheer and shout to the heavens. All of them landed square in my gut and knocked the wind right out of me. May everything we read leave us so pleasurably breathless.

Recent Romances:

A Gentleman Never Keeps Score by Cat Sebastian (Avon Impulse: historical m/m):

I keep picking up Cat Sebastian’s romances on account of irresistible paradox: they are always profoundly surprising in some way, and at the same time they are consistently, reliably excellent. They stick in the mind: Ruin of a Rake’s intricate social balancing act, It Takes Two to Tumble’s sparkly quasi-supernatural tone, The Lawrence Browne Affair’s Gothic indulgences. And now her latest book, the second about the ramshackle Sedgwick siblings, pairs black boxer-turned-pub owner Samuel Fox with disgraced semi-aristocrat Hartley Sedgwick, as they plot to discover and steal a set of scandalous paintings owned by Harley’s dead benefactor.

You’d think it’s a heist book. But it turns out to be more like a not-heist book — because of course in real life heists are usually an absolutely terrible idea. They’re precisely the kind of terrible idea a person would have if, like Hart, they were trying desperately to feel something other than traumatized by someone they’d trusted who’d hurt them enormously, and whom death had put beyond the reach of any actual punishment or revenge. And if you’re a decent, strong, caretaking type like Sam Fox, carrying around a lot of guilt about the people you’d lost before, you’d go to great lengths to keep someone like Hart from getting hurt any worse than he clearly already had been. You might even, say, help him break into a neglected house where some of that trauma took place, if Hart thought the paintings might be there, and it might help to find them. But mostly you’d do other, ordinary things: bring food, pour a drink, offer an understanding ear. Tell Hart he’s beautiful, make him feel safe.

Somehow, all the not-heisting turns out to be as engaging as a heist would have been. Hart and Sam are amazing on their own but absolute dynamite together: the scene where they meet may be one of my new favorite scenes in all of romance. There’s a lot about sex work and social stigma, racism and homophobia and snobbery and hypocrisy. It’s quite dark, at times, but there’s moments of absolute glory. Occasional romances deal earnestly and deeply with healing the damage left by sexual assault and rape; Courtney Milan’s The Governess Affair, for example. This book gives us a pair of heroes who know what it means to put their bodies and selves at risk for family. It makes it all the sweeter when they finally find each other.

Hartley broke the kiss and buried his face in Sam’s coat, but Sam could tell Hartley was smiling. God, it was a rare gift to have this man in his arms. It made Sam feel like he had been given care of something unspeakably precious and fragile.

The Duke I Tempted by Scarlett Peckham (NYLA: historical m/f):

I have never read a romance so reluctant to give up its secrets. Everyone is suffering and trying to hide it, from themselves as much as from the reader. And the few who aren’t suffering are up to something. It makes for a somewhat stony beginning — but as soon as one crack appears in the façade, the book becomes irresistible, like watching a ghost-riddled manor catch fire and burn to ash. You fly through the pages as the clock strikes ten, eleven, midnight — and then the book rips away the veil and you whisper holy shit against the darkness.

There was once a flourishing Gothic branch of romance, where women with voluminous nightgowns and voluminous hair fled sinister houses and sinister men by moonlight. Battered paperbacks embossed with names like Victoria Holt and V. C. Andrews were passed around from friend to friend, lurked briefly on the shelves of used bookstores, and then vanished seemingly into the ether. Then all at once the Gothic trend withered on the vine. Nobody quite knows why, and scholars who wish to study this question have trouble tracking down copies. The details of these half-remembered tales glimmer gemlike in memory: a secret room with a dead wife’s corpse locked inside, a peacock feather fan whose ribs are tipped with poison, an unlucky Australian opal that decimates an equally unlucky family. I devoured these books by the bagful, and none of the brooding vampires or burly werewolves of modern paranormal romance can pose a threat half as viscerally terrifying as They say he killed his first wife and now he’s asking me to marry him.

Oh, they’ll tell you this Scarlett Peckham novel is femdom, and it is — once it gets around to it — but in the excitement about that underexplored trope they won’t tell you about all the rest: the fire, the other fire, the secret marriage, the opium, the ballroom that becomes a forest, the iron key our hero wears around his neck, the child with a shock of white-gold hair who bears an uncanny resemblance to another child long dead. It was bone-chillingly spooky and when I wasn’t reading I was laughing with sheer delight.

Gothic romances are tempestuous by definition, but this one is dramatic even by those heightened standards: Archer and Poppy each say and do several things in the course of their marriage that would be unforgivable in a less turbulent book. We’re talking Heathcliff and Cathy levels of mutual desire and damage. If you want characters whose emotional compasses you trust not to lead them too far astray into frank rage and despair, well, you’re going to want to give this a miss. But if you want something to speed your heart and stop your breath as you read beneath the covers, with only the meager flashlight beam warding off the enveloping night — then you have a rare treat in store. Enjoy.

There was a piercing kind of emptiness in being cold to someone who was trying to be kind to you. She had thought it would be satisfying to trouble him but it only made her feel more bereft.

Sweet on the Greek by Talia Hibbert (Nixon House: contemporary bi m/f):

Nik, the Greek pro soccer player hero of Talia Hibbert’s latest contemporary gem, is not terribly bright. He hasn’t had to be: family wealth, stunning good looks, and athletic talent have given him everything he’s wanted. But now an injury means his career is behind him, and the future is a total blank. Nik may not be bright, but he is good, and he wants to do something meaningful, something to help the world.

But first he has to get the love of his life to like him, just a little bit. Just for a little while — say, the rest of their lives. And he has no idea how to go about it. Hence: fake relationship! It’s sure to backfire, and Nik’s just bright enough to know it, but he’s got no better ideas so hey, I’ll pay you to pretend to be my girlfriend at a month-long house party with my twenty best friends! He’s a hero of the type I think of as a Sex Puppy, muscular and rambunctious but inherently sweet and affectionate, like Chris Hemsworth’s Thor or Big Dick Richie from modern cinematic masterpiece Magic Mike XXL. Protective, but not prideful or authoritative — and gosh, doesn’t that feel refreshing in a world that sometimes feels stuffed to the gills with brooding alphas.

Heroine Aria Granger has good reason to be wary of brooding men: her last ex turned out to be someone stalking and trying to murder her best friend. Not a big surprise that she has serious trust issues! She’s questioning everything about herself — her instincts, her intelligence, her worth as a person. To Nik, though, she’s everything: sexy and witty and strong and brilliant and generous. Her deep uncertainty mixed with Nik’s absolute conviction is like nitroglycerin for the heart. This book is a Molotov, this book is a firework, this book will make you want to run around and dance and shout out of sheer joy. It’s funny, it’s filthy, and it’s sharp enough to cut. Run, don’t walk, et cetera.

He slid a hand under her head, cradling her skull, holding her to him as he kissed her again. He couldn’t speak. If he did, she’d hear the truth in his voice, hear the fact that he loved her in every crack and waver. So, instead, he kissed her, and hoped she wouldn’t taste it on his tongue.

A Duke by Default by Alyssa Cole (Avon: contemporary m/f):

Every now and then a heroine comes along who’s so engaging and so flawed and so marvelous all at once that you wish she was real so you could hang out and tell her how wonderful you think she is. Related: let’s never stop talking about Portia from A Duke by Default.

We first met Portia Hobbs as the hot mess best friend in book one of the Reluctant Royals series: she was funny and brilliant but she drank way too much and hooked up constantly and nearly messed everything up when she found out Thabiso was a prince. Now she’s landed a swordsmithing apprenticeship at a Scottish armory, as part of what she calls Project: New Portia, which is all about giving up booze and men and trying to figure out what the hell she’s going to do with the rest of her life. Her parents are driven and wealthy real estate tycoons, her twin sister Reggie runs a geek media empire from her custom-designed wheelchair, but Portia…Portia, according to her mother, is a “Jill of all trades, master of none.” The family dynamics here are so realistically painful that I had to read these scenes with my hands half over my eyes, cringing with the best kind of shared agony. If you know what it feels like to disappoint someone you love even though you’re trying your hardest, Portia’s your girl. I cried for her. I raged for her. And I loved her with my whole heart.

In a desperate effort to prove her competence, Portia pours herself into the armory, beefing up their social media and redesigning the website and oh yes, unearthing the fact that her boss (and our hero) is really the long-lost illegitimate heir of a royal duke. Tavish “Here’s My Eighteen-Inch Length of Steel” McKenzie is a silver fox Scottish-Chilean swordsmith who’s happiest in the shadows, so the title upends everything comfortable and familiar in his life, even as it gives him position and power enough to have real influence to make changes for good in the world. It’s tough on everyone, and the drama is riveting. This is a long, tense, slow burn of a romance: I almost worried — almost! — that they weren’t going to make it in time. We were racing toward the end of the book, and they still had not gotten their shit together! And Tavish was going to be meeting the Queen! And then the Queen was there and and and — and it’s a moment so spectacular, so jaw-dropping, so Peak Romance, such a gift to those who love this genre that I can’t even tell you what happens. You’re just gonna have to read it for yourself.

Now that she was here, the entire plan seemed ridiculous.

- Go to Scotland.

- Make swords.

- …?

- Prosper?

This Month’s Hot, Savory Romance to Make Your Mouth Water

This Month’s Hot, Savory Romance to Make Your Mouth Water: A Taste of Pleasure by Chloe Blake (Harlequin Kimani: contemporary m/f):

As you value your life and your reason, stay away from this book when you’re hungry. Genre fans know the secret: many of romance’s most decadent moments aren’t about sex at all. They’re about food. Many authors who write sex scenes with plain language and precise choreography will drop all realism and restraint to lavish hyperbole on an entree or a dessert or a glass of good wine. Food, like sex, is an ephemeral art form: you shop, you prep, you enjoy it — and then it’s gone. Category romances are a little ephemeral, too: short, swift stories designed to pack the maximum amount of punch into the minimum amount of book. Most of them are potato chips, briefly savory as they melt away, then you’re reaching for the next one. This slender little masterpiece, though, is lush and rich and complicated and memorable. Full of places and people and meals and wine. Bigger on the inside. It’s like a top chef’s best amuse-bouche, and I couldn’t have loved it more.

Toni is a perfectly cromulent hero — hot Italian winemaker with a troubled teen daughter and a troublemaking ex — but what I loved most about him was how completely he was into our heroine from the moment they met. Because Dani, our curvy black chef heroine with a temper and a weakness for terrible men, is an absolute marvel. She’s been working as a ghost chef, earning Michelin stars while her truly shitty on-again, off-again boyfriend claims all the credit for her work. Some sterner readers might be put off that she semi-cheats on him with the hero at the start of the book, but Andre so deserves cheating on, and Toni is so clearly a Fun Time Ready to Go, that I found myself actively rooting for Dani to let her guard down and just hit that already. In addition to the solid chemistry and great banter, we have a whole bundle of complex and beautifully rendered secondary characters (Dani’s driven, regal supermodel mom being a particular favorite) who help make this book feel like a complete world, briefly glimpsed. Good news: it’s a series!

Men, she thought. Watch, he is going to eat my whole dinner. Toni reached for a little plate and loaded it up with portions from each dish, taking care to select the best cuts, just as she would. Then he held it out for her to take.

Marking the higher standard to which we now hold ourselves

Discussion about Sarah Kendzior's The View From Flyover started on a positive note. I said I enjoyed the book, but thought the collection of essays — originally posts on Al Jazeera, mostly from 2013 and 2014 — had a bit too much crossover with each other, some points being made three or four times across as many essays.

Kendzior raises a number of important issues around poverty, lowering of wages, and full-time workers who are underpaid and living below the poverty line while doing the same work that others get much higher salaries for.

Others in the club agreed with me, one member feeling that this was the best written book we've read in the book club.

But one member raised concerns in a thoughtful way. She pointed out, for example, that Kendzior often failed to contextualize the history around her arguments, and at times, just made audacious claims.

In the essay "Academia's Indentured Servants", Kendzior pointed to a 2013 New York Times article, which she said reported that "76 percent of American university faculty are adjunct professors — an all time high."

That's a flip of what the article actually says, and leaves a gap where she draws flawed assumptions. The Times reported that 24 percent are tenure track positions, but the remaining 76 percent does not necessarily equate adjunct status, especially not the kind Kendzior highlights, living with outrageously low wages — that number also includes non-tenure lecturers who may have good pay and strong contracts at large universities.

As we talked through this member's concerns, some of the shine came off the book. We agreed that Kendzior tackled serious, important issues lyrically and with great verve and passion, but if she had offered greater historical context around some of her topics, or perhaps had framed this collection more as essays than journalism, it could have preempted some of the holes in her arguments.

Compared to other books we've read that decidedly brought receipts — Carol Anderson's White Rage, and Amy Goldstein's Janesville were both name-checked on this point — The View From Flyover Country is less authoritative when you start poking at its arguments, and that undermined our ability to trust it.

It seems that in this age of outright bold lies, we need to hold essayists and journalists arguing for positions we believe in to a very high standard. An epilogue from September of 2017 does talk about how bad things are after the 2016 election, but it doesn't look back and give any context to the essays preceding it, and some of us were curious how the Kendzior of today reads her own work, five years past.

One moment in the book proved not only prescient, but reading it in retrospect flips the meaning of the words in that most deliciously tragic way. It's where Kendzior quotes Turkish PM Erdogan from June of 2013, talking about Turkish protestors:

"There is a problem called Twitter right now and you can find every kind of lie there," he told reporters following days of mass protest in Istanbul. "The thing that is called social media is the biggest trouble for society right now."

Join us on Wednesday, September 5th, at Third Place Books Seward Park for the next Reading Through It Book Club. We’ll be discussing Kurt Andersen's Fantasyland: How America Went Haywire. You can buy the book for twenty percent off right now at Third Place Books in Seward Park.

Book News Roundup: Eroyn Franklin retires from Short Run, Lindy West's TV show gets picked up by Hulu

Two big bits of news!

- Yesterday, Short Run announced that a cofounder, cartoonist Eroyn Franklin, was retiring from the organization in order to focus on her comics work. This is not the end of Short Run by a long shot: in fact, as Franklin writes in her farewell note, it's a new beginning for the organization:

A year ago, [Short Run cofounder] Kelly [Froh] and I started planning a strategy that ensured the continuation of Short Run under Kelly’s leadership. We have carefully selected a new and active board of directors who share our vision for Short Run and who will help Kelly carry the organization into its next phase. If you love what we built and want to make sure it thrives, please continue to support Kelly and Short Run as you always have. Without me, Short Run will survive, but without all of you, it won’t. Offer what you can—time, money, energy, and participation in Short Run events will help keep the organization and the community we’ve built together fueled and going strong.

In weeks to come, I'll be talking to Franklin about what's next for her and what leaving Short Run was like, and I'll also be talking with the new Short Run board members about what they have planned for the organization as it moves ahead. Stay tuned.

Yesterday, news broke that Hulu bought a six-episode season of Shrill, a sitcom based on Lindy West's memoir of the same name. Saturday Night Live star Aidy Bryant will be starring in the show, which is filming this summer. Bryant will star as a journalist named Annie, which means the show is presumably based in part on the sections of Shrill that were set at Seattle alternative weekly The Stranger (where, full disclosure, I worked with Lindy for a few years.) Hedwig and the Angry Inch writer/director/star John Cameron Mitchell is costarring on the show. This is going to be good.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Superman runs down the clock

We are now halfway through Doomsday Clock, the 12-issue Watchmen...sequel?...written by Geoff Johns and drawn by Gary Frank, and I still have no idea what to think of it. Is it fan fiction? Is it an earnest attempt at a sequel? Is it supposed to be funny?

It would be easier to tell if Doomsday Clock had a consistent tone. This is a book that completely misunderstands Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's postmodern riffs on superheroes by reveling in their "coolness." The most recent issue features a Watchmen character massacring DC super villains in a scene that is clearly supposed to impress readers with its badassness. Previous issues featured a resurrection from the dead that is just as cheesy as a plot twist you'd find in one of the old cliffhanger serial films Ozymandias mocked at the end of Watchmen.

In the end, of course, it doesn't matter. Watchmen will still be there, long after Doomsday Clock is forgotten. And Watchmen isn't even as good as you remembered it, anyway. But the fact that it's taken six issues at $4.99 a pop to get exactly nowhere in the story is downright criminal.

"I believe in the power of these icons. I believe in the power of hope, and optimism," Johns told SyFy when Doomsday Clock was announced. That doesn't reflect anything I've seen in the first six issues of Doomsday Clock.

Surprisingly, another DC Comic is honoring exactly those values. When writer Brian Michael Bendis jumped ship to DC after umpteen years of exclusivity at Marvel Comics, readers expected Bendis would take on a street-level hero like Batman as his first project. Instead, he decided to write Superman. And, honestly, Bendis's Superman is exactly what the character should be: powerful, optimistic, friendly, and warm.

My one regret is that Bendis launched his time on Superman with a plot that involves yet another mysterious character from Krypton's past. As I've written before, the sci-fi trappings of Superman are the least interesting part of the character. Nobody has ever given a shit about Krypton.

People read Superman comics for the same reason they watch Mr. Rogers: they want to believe in a morally good universe, one in which right triumphs over wrong because it is right, not because it's strongest. If Bendis can maintain the essential decency of the character in months to come while telling stories that get to the heart of Superman's appeal, odds are good we'll be remembering Bendis's Superman run long after the mess that is Doomsday Clock has faded from our memory.

Book News Roundup: Digging in the backlist

This is not strictly book-related, but if you belong to the local-news subReddit called r/SeattleWA, you should know that the moderators are horrendous racists and apparently not good people. Some former SeattleWA members have started a new subReddit called r/SeaWA.

The entire archive of The Believer is now online and available to read for free. For about four years there, from 2004 - 2008, The Believer was the best literary magazine in the world. The organization has changed hands in recent years, from McSweeney's to the Black Mountain Institute. Perhaps under new and reinvigorated leadership it will regain its crown. (And if you're looking for a local angle, you should know that former Hugo House operations director Kristen Radtke is the art director and deputy publisher of The Believer.)

Need a good book recommendation or twelve? You should dive into this Twitter thread of books from the last ten years that were grossly underrated:

I've been thinking about the inertia of literary buzz, the way it's so often a self-fulfilling prophecy, and about great under-exposed books. Can we start a signal-boosting thread of books from the past 10 yrs that deserved way more attention? I'll start...

— Rebecca Makkai (@rebeccamakkai) July 29, 2018

Related: I've always been bummed that books, which are a relatively sturdy communication method, have such a short "shelf" life. That is to say that books, like movies, are launched into the world to some media buzz and then they succeed or fail, only to be forgotten when the next crop of new books arrives. It doesn't have to be this way. We should all try harder to dig into backlist, to uncover those books that didn't get the appreciation they deserved on publication.

A "spectacular" ancient library "that may have housed up to 20,000 scrolls" has been unearthed in Cologne.

On silencing

By now, you have probably at the very least read something about Minnesota poet Anders Carlson-Wee's poem for The Nation. The poem was written in an objectively bad imitation of African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), it contained some ableist slurs, and it was supposedly about the relationship between homeless people and passersby on city street. It wasn't very good, and a lot of people on Twitter dragged Carlson-Wee for writing such a bad and thoughtless poem. Eventually both he and The Nation's poetry editors apologized.

And now, of course, if you check Carlson-Wee's mentions on Twitter or read center-left blogs, you'll see plenty of examples of the outraged-by-outrage rants that have replaced actual cultural criticism in the mainstream since the election of Donald Trump. People (mostly older, mostly white) are whining that Carlson-Wee was "silenced," that the "PC mob," drunk on its "outrage culture" has fed on another innocent victim.

Never apologise for something you create. Stand by your words, you meant them when you said them so stand by them. Art is one mans appreciation of anothers perspective on the world. B/cos of what you've created we've been able to see the perspective of others. Your gift is ours.

— Chris Kemp (@VinylPugilist) July 30, 2018

It’s absolutely horrible that a person can no longer express their perspective of a marginalized people without this kind of (mostly) false outrage. I cannot begin to understand that backwards direction we are now heading. We’re more segregated than we’ve ever been. It’s sad

— Will O'Connor (@CharmCityProse) July 30, 2018

You did nothing wrong, and you certainly should not be apologising. The way you've been treated by your publisher is unethical and disgraceful. Some advice: it's always best not to grovel to a mob - there are plenty of people who will support you if you're strong and defiant.

— Russell Blackford (@Metamagician) July 31, 2018

But here's the thing: I see a lot of these complaints about silencing and "Twitter mobs" and so on. But those complaints are built on hot air and nonsense. Who was actually silenced here? Carlson-Wee wrote a poem, people voiced their opinions, Carlson-Wee apologized, and so did The Nation. If he wanted to, he could run the poem elsewhere. Why is Carlson-Wee's freedom of speech worth inherently more than those people on Twitter who also exercised their freedom of speech? And for that matter, how was Carlson-Wee silenced? He still has a Twitter feed, he still has a book coming out next year, he's still been published in many magazines. The Nation still exists. Nobody lost their jobs.

So what, really, is the problem? Is it that people should be allowed to publish bad poetry without any repercussions? Or is it that white people should be allowed to write in a thoughtless and inconsistent version of AAVE without facing criticism from Black people? Is it that people aren't allowed to say when they find ableist language to be offensive? Was it that too many people responded to the poem? Would one thoughtful essay in response to Carlson-Wee's poem, say, published in the New York Times be acceptable? Or would that critical response, too, be too much for Carlson-Wee and The Nation to endure?

So far as I can see it, nobody's freedom of speech was violated here. Nobody suffered any physical harm. The people who are upset over the "PC mob" seem to be concerned that the status quo as they see it is being attacked by people who are unlike them. This makes sense. The status quo serves them, and has served them for as long as there has been a United States.

Now they're afraid that one day they're going to feel as irrelevant and marginalized as they've always made everyone else feel. They don't want to share the stage. They don't want to think about the consequences of their actions. They don't want to be aware of everyone else's feelings. The world is changing, and they're scared. I can't really find it in my heart to muster up even a moment's sympathy for any of them.

A conversation with Rachel Heng about dystopia, death, and the marketability of a book titled "Suicide Club"

Last week at Elliott Bay Book Company, I interviewed Rachel Heng about her extraordinary debut novel, Suicide Club. Heng was a cheerful, generous interviewee — perhaps not what you'd expect from an author of a raw and intelligent sci-fi novel set in a dystopia that has conquered death. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of a portion of our conversation.

When I saw that your novel was titled Suicide Club, I could imagine hearing the Henry Holt marketing department's butt cheeks collectively clench at the thought of marketing the book. Seems like the word "suicide" might be a hard sell. Did they try to convince you to change the title at any point during the publication process?

Well, interesting story: At one point, I wanted to change the title, to Lifers. And they told me that was a terrible title. Well, they were more like, "oh, you should keep your original title." So actually, they were pretty on board with it from the beginning — they felt that it really got across the point of the book. I had my doubts, and for a while I had this other title that apparently sucked.

The book isn't dour or depressing, but it dwells in death and suicide. Was it challenging to keep your head in that space for an extended period of time?

I think my head is always in this space. I think the reason why I wrote the book was because I've always been quite preoccupied with death and loss. Everyone's had the experience where, when you were six or seven years old, you realize for the first time your parents are going to die. You're lying in bed in the middle of the night and you can't go to sleep and you're seized by this existential realization: 'my parents are going to die. What does that mean? I'm going to die at some point. Everyone I know will be dead and millions of people have died before me.'

And this is kind of something that stayed with me my entire life. I've spent lots of time thinking about it in what some people would call morbid ways. For me, it helps me appreciate my life better, always thinking of the fact that it's going to end.

So I think I wrote this book partly out of that fear. I don't think it was a difficult space to inhabit because it's something that I'm always inhabiting. And in a way, writing the book helped me address that — confront it face-on.

This is a dystopian novel, but it's very different than the dystopian fiction I've been reading lately. It's a different kind of doom. I thought before I read this book that I was suffering from dystopian fatigue, but your book feels completely different to me.

I didn't set out to write a sci-fi novel. And I think there's also this thing where, because of the Hunger Games, everyone assumes dystopian means [young adult fiction.] So when I started querying agents they were like, 'oh, this is YA,' and I'm like, 'do you see the title?'

I was kind of naive about the publishing industry. When you have a book coming out, you become hyperconscious of contemporary fiction and everything that's out there. But before that you're just kind of in your bowl and you have no idea what's coming out recently — you don't know about trends. I don't think I was super-aware of the whole dystopian trend until I was querying agents, and I read an interview with an agent who said 'dystopian fiction is so over,' and I was like, 'shit.'

I read a lot of dystopian fiction, but the older stuff. Brave New World was one of the most formative books that I read when I was a teenager. I'm from Singapore originally, and so I grew up in a very dystopian world. I didn't realize that until I was talking to a reporter for the national newspaper in Singapore and she said, 'I see a lot of stuff in the book that is reminiscent of how our government runs things. Did you do on purpose? Is this a satire?'

And I didn't intend for it to be, but I think it's just because I grew up in that world. And in many ways, I think it drew a lot from books like Brave New World and Margaret Atwood. And then as I was writing, someone told me to read Kazuo Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go. People had drawn comparisons to that, but I hadn't read it previously. If anything, I think I under-read dystopian fiction.

Yes, and we're all excited about the fact that Bob Woodward has a book about Donald Trump coming out this fall. Fear is supposed to be a heavily sourced work of journalism — like a Fire and Fury done right.

But please remember that no book is going to coax Donald Trump out of office. There's no piece of evidence that's going to send the president to jail. Feel free to read Fear, but for God's sake try to dedicate at least as much time as you spent reading Fear to phone-banking for your preferred candidates or doing get-out-the-vote volunteering in the midterms this year. No hero is coming to save the day; you're the hero, and you've got important work to do this fall.

Almost like being in love

Published July 31, 2018, at 12:01pm

From sci-fi premises about the search for a soulmate to a surprisingly affecting story of a homeless mother and daughter, Ruth Joffre's debut story collection examines the depth and breadth of love.

Eve

tilted pelvis toward a velvet sky

linted with stars

you offer your self

as sanctuary

present your softest place to be shined

into you tell the night that

you have held secrets like black holes,

surely you can take constellations

and the generations that will come

after these stars have died

will find their way through life

by the stars of your pussy

Cookout at Queen Anne Book Company? Sign us up!

Seattle7Writers is a tireless and creative supporter of the literary arts in this community. Each year they host dozens of readings and book events, as well as the Write Here, Write Now writing intensive, which is one of our city’s best come-one-come-all opportunities to put pen to page. And they work constantly behind the scenes, channelling donations to nonprofits working to improve literacy and creating opportunities for writers and readers to connect in person.

So bringing a group of local authors to a favorite independent bookseller, to cook up hot dogs (carnivore and vegetarian) and talk to the readers and writers who stop by, is just up their alley. And 20% of all book sales during the free event go directly to Literacy Source. That's an evening out.

Check out a full list of authors attending and other fine print on our sponsor’s page — and put this event on your calendar.

Sponsors like Seattle7Writers not only keep our readers in the know about upcoming events of interest — they support the great writing about books that you see here every day. Got an event, a book, or a residency you'd like to promote? Our 2018 sponsorships are almost sold out, but never say never! Move fast, and you can reserve a slot before they’re gone.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from July 30th - August 5th

Monday, July 30: Give Me Your Hand Reading

Megan Abbott's thriller is about a secret and a friendship and, as is usually the case with these sorts of things, betrayal. Abbott is an acclaimed thriller writer and she also writes for TV. (Real TV, like HBO, not some crappy sitcom.) Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, July 31: Seattle Poetry Slam Sendoff

See our Event of the Week column for more details. The Royal Room, 5000 Rainier Ave S, http://theroyalroomseattle.com, 8 pm, $10.Wednesday, August 1: Cracking the Sky Reading

Brenda Cooper is a prolific science fiction writer and futurist. She has written with Larry Niven, which basically makes her sci-fi royalty. Cracking the Sky, her most recent book, is a collection of short fiction that examines themes of environmentalism, which is a lifelong passion of hers. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.Thursday, August 2: The Annotated Big Sleep Reading

Owen Hill's latest book is an annotation of Raymond Chandler's classic detective novel. These annotated guides are a real pleasure to read, particularly in works that have maybe lost some nuance due to the time they were published in. While I haven't read this particular edition, I suspect that Chandler's work will feed well into the annotation format. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.Friday, August 3: Raven Chronicles Volume 26 Reading

The 26th volume of Seattle-based literary magazine Raven Chronicles is based on the theme "Last Call." That's because after this issue, they'll be ceasing publication of the magazine and focusing on an "ongoing book publication program." Tonight, a ton of readers will celebrate this last hurrah, and toast the future. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Saturday, August 4: Advice for Future Corpses Reaading

Sallie Tisdale is an award-winning writer and a palliative care nurse. Her most recent book is about how to die, and how to help your loved ones die, and what to expect in the dying experience. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Sunday, August 5: Ghost Of Reading

This is a reading to celebrate the debut collection of poet Diana Khoi Nguyen. She's joined by Montana poet Prageeta Sharma and Seattle poet Ryo Yamaguchi, who works at poetry press Wave Books. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 6 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Seattle Poetry Slam Sendoff

Seattle's lively slam community has lots of qualities to recommend it. Poets like Elisa Chavez and Troy Osaki are finding great success in both the spoken and written poetry worlds, for instance. Our youth slam community has maybe never been better. And our slam poets win awards on a very regular basis.

But maybe my favorite part of Seattle's slam community is the sendoff party culture that we have. It works like this: whenever Seattle sends a team to represent us in some national competition, the community throws a big party to celebrate the Seattle team's accomplishments and to wish them luck in the fight against other cities. (It's also a fundraiser; it's expensive work sending poets cross-country.) The event is kind of like sports, only there are no concussions and nobody is going to boo you for kneeling for the national anthem.

Seattle traditionally places in the top third of national slam competitions, but this team might go even farther. The four poets representing us in Chicago are io Chanae, Ben Yisrael, Garfield Hillson, and the great Ebo Barton.

This Tuesday night, visit the Royal Room to see the team in action, to get them psyched up for their big poetry fight on the national stage, and to pay for their travel and lodging and beer expenses. It's time to celebrate our community, and to stand up for Seattle artists.

The Royal Room, 5000 Rainier Ave S, http://theroyalroomseattle.com, 8 pm, $10.

The Sunday Post for July 29, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

This week’s Sunday Post is a recorded message. The Sunday Post is sitting by a river; in fact the Sunday Post has her feet in the river and a book in her hand. But she doesn’t have a cell connection or wifi.

So although this column is supposed to be the best of the past week’s internet reading, that’s not going to work. I’m in a spot where major events include “wow, I really thought that bee was dead!” and “did you see the weird shape of that rock?” — not “HOLY CATS IT’S THE END OF THE FREE WORLD … AGAIN.”

When I took on the Sunday Post, I didn’t read much that wasn’t printed on a page. I didn’t follow Twitter (now I have multiple lists); I didn’t have a newsreader (now it's Feedly, and it works okay, not great). Donald Trump had only just been elected, and the news cycle was only just feeling the first hit of that drug — starting to hear its heart pound in its ears. (Oh, news cycle, we are so, so sorry.) I did not at all understand the river I was putting my feet into.

There’s a lot of great writing on the Internet, and I let a lot of it flow through me every week to try to find a few things other people might want to read too. Sometimes it’s a delight, and then suddenly sometimes it’s not.

It's similar to staying in Elliott Bay or Powell’s for too long — that tipping point between “oh my god, all the words!” and “oh my god. all the words.” Words that investigate politics, the heart, the author’s childhood. Words that profile people and places and animals. Words that are angry — a lot of angry words, these past eighteen months, some restrained and analytic, some furious, some in mourning.

They’re all worthwhile but they’re all coming at us so fast, it could knock you off your feet. I don’t know about you, but I can’t put the internet down. I’m mainlining that son of a bitch.

This week’s articles have all appeared in the Sunday Post before, or should have. They’re the essays that I remember, without looking back at the archives, because reading them was an event, a thing that happened, like the sun startling a bee awake and into flight.

And the words in these essays make everything stop. They’re absorptive in the way that reading on the page is — they aren’t necessarily quiet, but they pull you into that quiet place. These are some of the hardest pieces to feature each week, because all I really have to say about them is: read this.

This week’s Sunday Post says, even more than usual, read this.

In the meantime, where I am today, all the words are back on the page, and their speed is set to the pace of slow, cold water. Hey — did you see the weird shape of that rock? Cool.

The Survivor’s Guide to Kerouac Country

Kate Lebo on Kerouac and book tours and fear and freedom.

I want sympathy. I want to feel safe. I want to explain why I’m not home in my little Seattle fishing village, which isn’t little anymore, which my friends and I helped make not-little before a new cycle of wealth kicked us out and welcomed people who could afford the new cute neighborhood. What am I trying to say when I explain how, while living in that old Boeing cottage, I couldn’t walk into a grocery store without clucking over a baby plant? That I bought peat pots of lemon verbena instead of clothing or art or shaving cream because growing things made me feel good about living alone? That I loved living alone? That I was miserable. I want to explain how strange it is to walk through a garden without mothering. My home is my body, some poem probably goes. No shit. To feel that way makes the road possible.

Nightingale: A Gloss

Paisley Rekdal on poetry and violation and beauty.

Perhaps the greatest desire a victim of violence has is to look, in memory, at that violence dispassionately. But remembering, the heart pounds, the body floods with adrenaline, ready to tear off into flight. For some, there is no smoothing chaos back into memory. Poetry, with its suggestion that time can be ordered through language, strains to constrain suffering. It suggests, but rarely achieves, the redress we desire. Language does not heal terror, and if it brings us closer to imagining the sufferer’s experience, this too does not necessarily make us feel greater compassion, but a desire for further sensation. If we cannot articulate pain beyond inspiring in the listener a need for revenge, we only speak of and to the body.

My Romantic Life

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore on Seattle and San Francisco and — and — and I still hesitate to try to capture this one with anything but metaphors.

The second time I did porn it was with Zee, when we were boyfriends, and I’d just remembered I was sexually abused, so I was taking a break from sex, but then Zee called me to do the video because his costar showed up too tweaked out — I did it because I needed the money, but then Zee got upset when I couldn’t come, and I felt like a broken toy. Which is how I’d felt with my father. When I walked out into the sun after that first video shoot I just felt totally lost, like I didn’t even know where I was and why was it so hot out, maybe that’s why I felt so dazed.

Hello, Goodbye

Jessica Mooney on saying goodbye.

I don’t know how to say what I mean. As a kid, I mixed up the words for things. Cat, I’d say, pointing at an alarm clock. Taxonomy remains mysterious. Walking around my neighborhood, I don’t know the names of things. Sinister witch-fingered bramble. Orange thing I want to call persimmon. The part of the foot that keeps me upright. The sinewy blue veins under the tongue. How do I not know the basic recipe for standing and speaking?

I love you. I wonder if I hear the words in the same place I hold my missing father. My brain’s translation: goodbye, goodbye, goodbye.

The Loneliness of Donald Trump

Rebecca Solnit on the story Donald Trump is living inside.

He was supposed to be a great maker of things, but he was mostly a breaker. He acquired buildings and women and enterprises and treated them all alike, promoting and deserting them, running into bankruptcies and divorces, treading on lawsuits the way a lumberjack of old walked across the logs floating on their way to the mill, but as long as he moved in his underworld of dealmakers the rules were wobbly and the enforcement was wobblier and he could stay afloat. But his appetite was endless, and he wanted more, and he gambled to become the most powerful man in the world, and won, careless of what he wished for.

Twenty-Six Notes on Cannibalism

Anca Szilágyi on Goya and cruelty and art.

That giant, lit by the moon, looks over his shoulder somewhat upward, lonesome.

On Being Driven

Hugo House's newest prose writer in residence, Kristen Millares Young, on the weapon of history.

I worried about going to jail on this island, where he would know everyone watching over me inside. Worried even about stepping into the building to make a report. And what would I have said? That we had a dangerous conversation. That he left bruises on my mind.

That I cursed him. That I cursed him, and he believed it. That I cursed his family, threatened to rain down destruction on their black bodies, invoked centuries of white oppression, and he believed me because he lived that truth.

That I would do it again, and again, and again, just as he hoped to do me.

Night Life

Amy Liptrot on what survival requires for birds, and people.

I keep stopping at places where I heard a male calling last year but I hear nothing. In recent years, there has been a slow and steady upwards trend in numbers, and the RSPB’s Corncrake Initiative was a success story. But this year has been very disappointing: the number of verified male corncrakes calling in Orkney dropped from 32 to just 14. Back in the office, sleep-deprived, I fill in zeroes in my spreadsheets. I am depressed about corncrakes. Somehow it is as if my fate becomes intertwined with that of the bird. I’m trying to cling onto a normal life and stay sober. They are clinging on to existence.

Slow Pan

Bryan Washington on finding yourself in the stories on screen.

The audacity required to ask if we need another gay movie, if we need any more gay movies, transcends thinking altogether. It is a thoughtless question. You only ask it if you’ve seen yourself so ingrained into the culture, into the fabric of the world, that your absence from those seams is unthinkable. You only ask that question if you’ve never been repulsed by yourself, or the idea that anyone like you, anywhere, could be happy. You only ask that question if you don’t know what it means to feel like the only person on the planet.

Whatcha Reading, Austin Woerner?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Austin Woerner is a Chinese-English literary translator. In addition to Su Wei's novel The Invisible Valley, just out from Small Beer Press, he has translated two volumes of poetry, Doubled Shadows: Selected Poetry of Ouyang Jianghe, and Ouyang Jianghe's book-length poem Phoenix. Formerly the English translation editor for the innovative Chinese literary journal Chutzpah!, he also co-edited the short fiction anthology Chutzpah!: New Voices from China. He holds a BA in East Asian Studies from Yale and an MFA in creative writing from the New School, and is currently a lecturer at Duke Kunshan University just outside of Shanghai. He's appearing tonight at Elliott Bay Books to talk about The Invisible Valley.

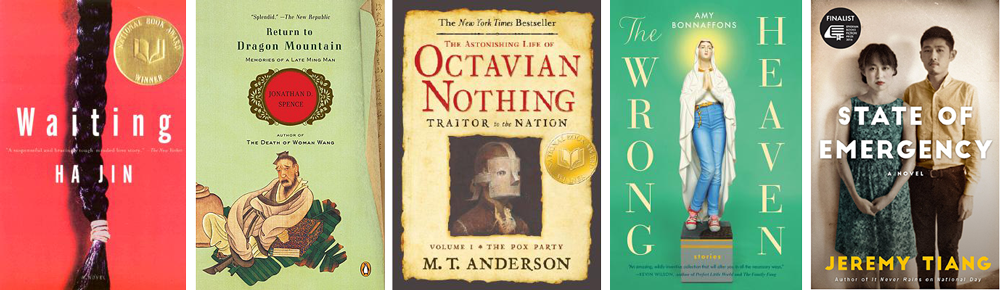

What are you reading now?

I've been rereading Waiting by Ha Jin. While I was translating The Invisible Valley I actually steered away from fiction set in China, because I wanted to develop my own ear for how to evoke a Chinese cultural setting in English. (I guess you could call it "reinventing the wheel.") But now that I actually live in China, I'm more and more fascinated by Chinese emigrant writers like Ha Jin and Yiyun Li, who write in English about experiences they had back in China in more or less the same time period as The Invisible Valley is set. (And in such beautiful English! As an EFL writing teacher I'm in awe of people who develop a fine literary style in a foreign language.)

What I like about Waiting is the way its main characters feel so real, their emotions so relatable, despite the fact that their culture and life circumstances are so vastly different from the novel's intended readers. At the same time, living in China has given me an appreciation for certain dimensions of their experience I wouldn't have understood well before. Back in the Maoist era people had such little latitude to make decisions about their own lives. So the story's drama takes place in the tiny range of motion available to them. Obviously things've changed a lot since then, but some things still resonate.

What did you read last?

Over the past year I've been dipping in and out of Jonathan Spence's Return to Dragon Mountain. Spence recreates in novelistic detail the life and times of Zhang Dai, a Ming-dynasty aesthete and man of leisure known for his gem-like prose essays. Zhang's world is the that of the "scholar gentry" of the lower Yangtze delta, a privileged elite who passed their days in painting, poetry, tea connoisseurship, and other charmingly frivolous-seeming hobbies. Zhang famously said, "A man with no excesses is not worth befriending," and Spence conjures Zhang's character through his obsessions: finding the perfect springwater to brew the perfect cup of tea, directing amateur operas, inventing witty taxonomies to categorize the different kinds of people who go boating on West Lake in Hangzhou, and so forth.

Though it's easy to laugh off Zhang's pastimes as the dissipations of a silk-slippered aristocrat, it's not hard to see parallels to our contemporary era of abundance. When your basic needs are already amply met, what do you do with your time to give meaning to your life? (Later, when the Ming dynasty fell, his family would lose everything, and that foreknowledge lends his reminiscences the air of an elegy for a lost world.) The area where I now live and teach is more or less Zhang's home turf, and though the freeways and freight barges and endless factories of the modern-day Yangtze delta are a far cry from Zhang's pleasure boats and gardens, I feel like Zhang's spirit hovers over them still.

What are you reading next?

This summer, taking The Invisible Valley on tour in the U.S. has given me the opportunity to meet many new literary friends and reconnect with old ones, and their books are now weighing down my China-bound suitcases. A few I'm especially excited to read are The Wrong Heaven by Amy Bonnaffons, The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing by MT Anderson, and State of Emergency by Jeremy Tiang. You should check 'em out too!