Laura Da' loves the privacy of writing in public

The poet Laura Da' has been a notable name in Seattle for a good long while now. But a few years ago, it felt like Da' started appearing everywhere. She showed up on bills at group readings, and she appeared as a featured poet at book launch parties, and she taught workshops at the library. Da's ascension into the upper echelon of Seattle's literary scene happened gradually, but once you noticed that she had become an important figure, that realization felt right and good.

As you can see in the poems Da' has published with us as our Poet in Residence for the month of November, she is a meticulous and thoughtful poet. She works frequently with finely wrought couplets, often revolving around a single powerful word or image. A good Da' poem feels to me like a delicate string of glowing pearls, hung on a string of silver so finely crafted that it's almost invisible.

Over coffee, I ask Da' if she agrees with my assessment that she one day seemed to be ubiquitous in Seattle's poetry scene, after years on the edges. "I have a son who is eight now," Da' tells me, "and so there was a good amount of time where I was pretty limited in my ability to be out and about." She also points to the 2015 publication of her first full-length collection, Tributaries, as a moment in which her relationship to the city changed.

"I think that I've always been well connected in the indigenous poetry community," Da' says, "because I started my education at the Institute of American Indian Arts, and there are so many writers who have come out of that school. It's a tight, small community generally speaking, though it's incredibly vast in terms of talent and experience." She felt a part of that community almost immediately.

But even though she was born and raised in the Snoqualmie Valley, and lived most of her life in western Washington, breaking into this city's poetry community took more work. "Seattle is not easy to get in the door, I think, which is really unfortunate," Da' says. She says Seattle's literary community has a fair share of "gatekeepers" who aren't especially good at making new voices feel welcome.

But then "I was a Jack Straw fellow and Hugo House fellow and that really helped me," Da' says. What was it about those two programs that worked for her? "I met a lot of wonderful writers and good friends. I'm fairly introverted and shy, so usually I need an extrovert to sort of adopt me. And that was the way I found a place in the Seattle poetry community."

Da' is not one of those poets who have been writing poetry since she could first pick up a pen. She started at the Institute of American Indian Arts with "an idea that I wanted to be involved in museum studies," but then she met poet Arthur Sze, who was an instructor at the school and "a really incredible poet." His work inspired her. "I was 17 and in college and that's when I started writing poetry. I changed majors almost instantly."

What was it about poetry that spoke to Da'? "I really like the ambiguity of poetry and I also hate to be told what to do, ever. So poetry is really appealing to me," she laughs. And it appeals to her inner introvert because it's "a meditative art that feels nicely private even though it is public. There's an element of privacy that I really like."

When Da' writes a poem, she says, she's "looking at the tiniest little elements and sometimes they seem so discreet — molecular, maybe ,is a better word." She calls her poems "very finely constructed," and as she does so she mimes someone repairing a watch, leaning in close to the table and working with delicate tools to place a gear that's almost invisible to the naked eye. "They've taken me a very long time," she says.

She's very aware of the whole scope of her career, and Da' is always trying to stretch her abilities. "I'm a young writer and I don't want to move into a territory where I no longer feel like I'm an emerging writer." She cites her poem "Centaur Culture" as an attempt to do something new. "I'm trying to challenge myself with more of that sort of lyrical essay or prose-poem kind of work. Anytime I feel more established I always try to shift into something a little different."

Da' is happy with the reception her work has received, but she does think a lot about "how my poetry is categorized. I think that it's limited by mainstream publications' desire to essentialize non-white, non-dominant narratives."

Da' explains, "very often in any review [of my work,] it'll talk about how it's a Shawnee document." That's not inaccurate, of course — "I really appreciate my roots as an indigenous writer. My community is indigenous writers, and that's my most important audience, too."

That said, "I do think the dominant mainstream publication industry is much too apt to want to essentialize my work. And I think that institutional racism still allows people to view it through a lens that makes it lesser." The comments that seem to sting most for her are those reviewers who seem surprised by how finely rendered her poems are, as though indigenous poets can't be watchmakers, too.

"There are so many fantastic indigenous poets," Da' says. "There are so many poets who have been trapped by the institutional racism of publication for so long that to have people still apply that worldview feels really wrong and also sort of infuriating."

The poets who influence Da' range widely in terms of style and background. Da' gushes over poems by Danez Smith, Natalie Diaz, Sherwin Bitsui, and Cassandra Lopez. She speaks again of Sze's "respect for the reader and the reader's ability to handle the ambiguity of the unanswered."

She most likes how you can return to a single poem by Sze "every decade, and the more you've learned, the more the poem sings out to you. It's so admirable to me to create something that is beautiful on the first reading, but rewards every single subsequent reading, too."

Da's so enthusiastic about Sze's writing that she doesn't seem to realize that she could just as easily be describing her own work — these elegant couplets crafted from the smallest and most delicate materials, but which only grow finer with age.

Book News Roundup: Is this the end for Amazon Books?

Congratulations to Seattle Civic Poet Anastacia-Renee, who Humanities Washington just announced as this year's James W. Ray Distinguished Artist, and to poet Cassandra Lopez, who is a recipient of the James W. Ray Venture Project Award. Also, the press release kind of buries the fact that this is the last year of the James W Ray awards, which annually gave $80,000 to local artists.

The Washington Ecopoetry Map provides an online map of poems that specifically mention various Washington state natural landmarks. Click around on this one for a while and you're likely to find a new poem to love.

If you're a freelance writer, please sign up for Obamacare now. The deadline is December 15th.

No jump shots. No ferns. No memes. Not this time. I’m going to give it to you straight: If you need health insurance for 2019, the deadline to get covered is December 15. Go to https://t.co/ob1Ynoesod today and pass this on — you just might save a life. pic.twitter.com/8mHMsXGY0g

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) December 10, 2018

Is Amazon giving up on the Amazon Books model already? This post at the Digital Reader indicates that Amazon has backtracked on three potential Amazon Books locations, but the company told Geekwire that they're still "excited" about physical bookstores. We'll see, but I think there's plenty of reasons to doubt the sincerity of Amazon's commitment to brick-and-mortar bookselling.

I'm okay with the fact that I did not make the list of 2018's most scathing book reviews. A scathing book review is fun to write, but it should be the most sparingly used weapon in a book reviewer's arsenal. Negative book reviews are great, of course, but a little bit of performative outrage goes a long way.

On being over my head in a black hole

My grasp of science, at this point, is fairly pathetic. What little I understood in high school is basically gone by now. For me, science is pretty much a matter of faith. I take it as a matter of course that people who are smarter than me — people who have devoted their lives to science — know what they're doing, and I follow their advice on topics like climate change and vaccination.

I know that my phone works when I want it to. I know that we have satellites in orbit around the planet and an awesome well-digging robot on Mars. Do I know how we did any of it? No. I only have a rudimentary understanding of scientific advancements: basically, in my head, I picture science with all the nuance of a child's crayon scrawling. That's what our species's tendency toward specialization is all about — or so scientists tell me.

That said, I love to dabble in scientific books. Reading about science feels, to me, like a calisthenics of the mind: I can stretch my brain and try out some concepts that would never have occurred to me otherwise. The secret to reading science books, for me, is the understanding that I'm not going to understand everything that I read. I'm just kind of forcing my way through the book and coming to terms with the fact that, unlike most books that I read, comprehension is not always possible.

This is a long way of saying that I'm not reviewing Chris Impey's book Einstein's Monsters: The Life and Time of Black Holes. I'm not reviewing it because I didn't understand all of the book — my guess is I only really got about 65 percent of it.

This is not Impey's fault. He's a clear and straightforward narrator, and his explanations will definitely make sense for a general audience. But there were parts of this book that I skimmed because my poor dumb lit-drunk brain simply couldn't absorb the information properly.

So why would I bother reading a book that I'm constitutionally unable to understand? It's because science writing is so abstract that I'm able to appreciate the poetry in it. Impey tosses off facts that are so gorgeous and so difficult to grasp that they're practically poetic imagery. Consider:

- "The farther away a galaxy is, the faster it's receding; in fact, every galaxy is moving away from every other galaxy."

- "As a star evolves it keeps a delicate balance between gravity, which is always pulling inward, and pressure from fusion reactions, which pushes outward."

- "Normally these pairs of particle and antiparticle, or pairs of photons, disappear with no effect. But close to the event horizon of a black hole, intense gravity can pull the virtual pairs apart. One falls in and the other flies away and becomes real."

- "They've weighed black holes by the thousand. This research has taken away black holes' shock and awe, and given them an air of inevitability — which doesn't make them any less amazing."

- "Think of black holes colliding as a gravity bell ringing."

Impey leaves a trail of delicious metaphors throughout Monsters — a long line of bells and corks bobbing in the water and elevators hurtling through space. The message behind those metaphors might be lost on me, but the metaphors themselves are beautiful. For some people, at some times in their lives, the search for truth is more important than the truth itself.

leaving my therapist’s office after a breakthrough

As soon as I unlock my phone,

out falls a tiny mother

asking her grown son to call

back when he finds the time plz,

out falls the strained voice of a debt

collector after several

attempts to reach you,

out falls a school

with a shooter & everything,

out falls a riot, out falls a child

texting another child how scared she is

from under her desk

with all the curtains

drawn, out falls

an election,

a special election,

a compromised election,

& another smoked quartz riot,

out falls a pair of unconcerned liquid gold legs at a hotel pool,

out falls Tommy Le’s pen,

Sandra Bland’s signal light

a stack of Alton Sterling’s bootleg CDs, out falls

a powerful man awash in disgrace & another terrible man

& another terrible man

& Jesus —

until out falls Janelle Monaé,

plentiful & perfect

-ly formed.

At what point, exactly, does grief start?

This onslaught of self-

portraits in convex mirrors—

each moment more upside down

was to know what time it was.

pǝʇuɐʍ I llɐ ⅋

˙sɐʍ ʇᴉ ǝɯᴉʇ ʇɐɥʍ ʍouʞ oʇ sɐʍ

The downfall of Albert Lesiak

It's rare that our attention is captured in just a few lines, but drop yourself anywhere into the first chapter of The Hollow Middle, and you'll find yourself caught up. Popielaski's style is an organized four-car pileup, with just a bit of an echo of Joyce, a bit of an echo of Eliot. You can see empathy peeking through his gentle mockery of his protagonist; your smiles will be rueful, but you won't be able to restrain them.

Here's the opening:

Nothing is remarkable about the lightening hour and the mild fairgrounds air, and nothing is remarkable about the peeps and ribbits in the meadow where the birders, loyal to migration schedules, stalk when there is light to glimpse a little rarity, and nothing is remarkable about the yonder man, bespectacled, whose respiration is the stuff of late-stage hibernation.

Read more on our sponsor feature page, then buy the book.

Sponsors like John Popielaski make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you can sponsor us, too? We only have three slots left in the first quarter of the year (and we haven't even gone public yet!). Reserve your week of choice before it's too late: Just send us a note at sponsor@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from December 10th - December 16th

Monday, December 10: Click Reading

Seattle photographer Bob Peterson, who has taken pictures of sports, nature, and local celebrities. Tonight, he chats with environmental artist Tony Angell about his long career and his new book of photos. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Tuesday, December 11: Penguin Book of Japanese Short Stories Reading

Local translator Jay Rubin is likely best known as one of the main translators of Haruki Murakami's fiction, but he's also translated plenty of other Japanese writings into English, including for a popular XBox game. Tonight, he celebrates the publication of a new book of Japanese short stories with a cast of readers.Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Wednesday, December 12: Journalism and Democracy in an Age of Misinformation

Marcus Harrison Green, who founded the South Seattle Emerald, will chat with a local journalism researcher about the importance of good journalism as part of Humanities Washington's ongoing discussion series. Naked City Brewery, 8564 Greenwood Ave N, 838-6299, http://www.nakedcitybrewing.com/, 7 pm, free.Thursday, December 13: Trolls in the Nordic Imagination

Lotta Gavel-Adams, whose name is almost a complete sentence, is a Swedish studies expert at the University of Washington. She'll discuss the Nordic obsession with trolls, which is a pretty fantasticNordic Museum, 2655 NW Market St, http://nordicmuseum.org/future, 7 pm, free.

Friday, December 14: Maged Zaher, Jamaica Baldwin

Seattle poet Maged Zaher is visiting town from his home in Georgia. Why do I call him a Seattle poet when he lives in Georgia? It's because Seattle helped to shape Maged Zaher's poetry in a meaningful way, and also because I refuse to accept the fact that he's left. He'll be joined by Seattle poet Jamaica Baldwin for an end-of-year reading at Arundel Books. This is likely to be one of the best readings of the year.Arundel Books, 212 1st Ave S, https://www.arundelbooks.com/, 4 pm, free.

Saturday, December 15: Sugar Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Chin Music Press Showroom, Pike Place Market, 380-1947, http://chinmusicpress.com, 3 pm, freeSunday, December 16: Meet the Grinch

This storytime for kids will include a special appearance by everyone's favorite Christmas-stealing bastard, the Grinch.University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 1 pm, free.

Literary Event of the Week: Sugar Reading

"Butter had bound them," Seattle author Anca L. Szilágyi writes in her new chapbook, Sugar. "A mutual love of butter." Sugar is a gastronomic love story about tastes and flavors and agreement and disagreement and all those other factors that make a relationship succeed or fail.

I'd wager that pretty much everyone who has behaved ungenerously in a relationship can see themselves in the opening lines of the book: "He couldn’t stomach currants in his salad. She couldn’t stomach his not stomaching her currants."

Set in and around Pike Place Market, Sugar is a kind of fairy tale, with food in place of magic. There are lamb's tongues and artichokes and lakes of butter and French food and other delectables that you can find in the Market. It's a delightful little amuse-bouche of a book, with an ending that will charm Seattleites and tourists alike.

This Saturday, Szilágyi will read Sugar in the Pike Place Market at the showroom of the book's publisher, Chin Music Press. She'll be joined by Seattle poets Montreux Rotholtz and Alex Gallo-Brown, who is publishing an exciting new book at Chin Music next year. This is a great little showcase celebrating local writers and a local press and Pike Place Market itself. It doesn't get Seattlier than this.

Chin Music Press Showroom, Pike Place Market, 380-1947, http://chinmusicpress.com, 3 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for December 9, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

High Elopement Risk

I’ve searched this piece by Jessica Mooney over and over, trying to choose a single quote that captures it. It’s impossible. Mooney’s writing mimics the way the mind dances around something too difficult to look at, repeatedly approaching and retreating. Wry, sad, reflective, angry, she shifts from the history of insomnia to her mother’s history of sexual assault, from cartography to her own ceaseless motion … Oh, just read it. It’s very, very good.

My mom, the Sudafed socialite of Chicago, called me in Seattle, fresh from an Aisle 4 gossip session. She could barely catch her breath. She couldn’t remember what she took or how many.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with me,” she said, pushing blooms of static through the phone. “What if … ” she gasped, “What if I’m a shadow who’s lost her person?”

What’s behind a recent rise in books coverage?

Overall, good news here: some of the losses to book coverage that came with the decline in print journalism are being recovered online. I still believe that “shareable” is not the final word (or even the first word) on what deserves focused attention; “yes” to writing about books vibrantly, imaginatively, passionately — “no” to dressing books in clickbait’s hand-me-downs. But I’m not going to quibble: more writing about books makes room for more writing about books, and that’s good for readers and authors alike.

Given the deluge of movies, TV, and tweetstorms, it may be more important than ever for publications to help books accomplish these goals. But the best format for them to do so is likely no longer the traditional, single-book, literary review. To break through the noise, editors must translate old-fashioned book coverage to the lingua francas of today’s impossibly paced media climate: shareable lists, essays, digestible Q&As, podcasts, scannable email newsletters, hashtags, Instagrams, even book trailers.

Thank You for Growing Up With Us

No, I am going to quibble, just a bit. Or let Tavi Gevinson, the editor-in-chief of Rookie, quibble for me. Her farewell letter as she closes out the seven-year publication is an incredible reflection on compromise, on becoming an entrepreneur, on growing up and knowing what you want (or don’t). And it’s a reminder that professionalizing creativity comes with a cost, especially online.

This organicness of Rookie was in part a testament to the way people rallied around it: the contributors and readers who were willing to share pieces of themselves and support each other. This is still happening, thanks to you, reading this, but organicness on the internet is not as easy now as it was back then. Rookie started in 2011, and to remind you where technology was then, I had a slide phone and no Instagram account. When I got home from school every day, I looked at websites on a desktop computer. To get to school in the mornings, I had to walk ten miles in the snow, and actually never even made it because I would trip and fall on my back and have to wait for hours for someone to stand me up because my coat was so puffy that I could not move. Nowadays, social media gets more of people’s eyeballs than publications do.

Whatcha Reading, Kristen Millares Young?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Kristen Millares Young is the author of the upcoming Subduction (Red Hen Press, spring 2020), as well as an essayist and journalist. She's the current Prose Writer-in-Residence at Hugo House. Mark your calendar now! See Kristen read, sing, and perform with a host of others in "Lit Jam: a Night of Words and Music" at Hugo House on March 8, and catch her off-site during AWP reading from “Every woman keeps a flame against the wind.” to celebrate Latina Outsiders: Remaking Latina Identity, in Portland, March 27 at the Milagro theater.

What are you reading now?

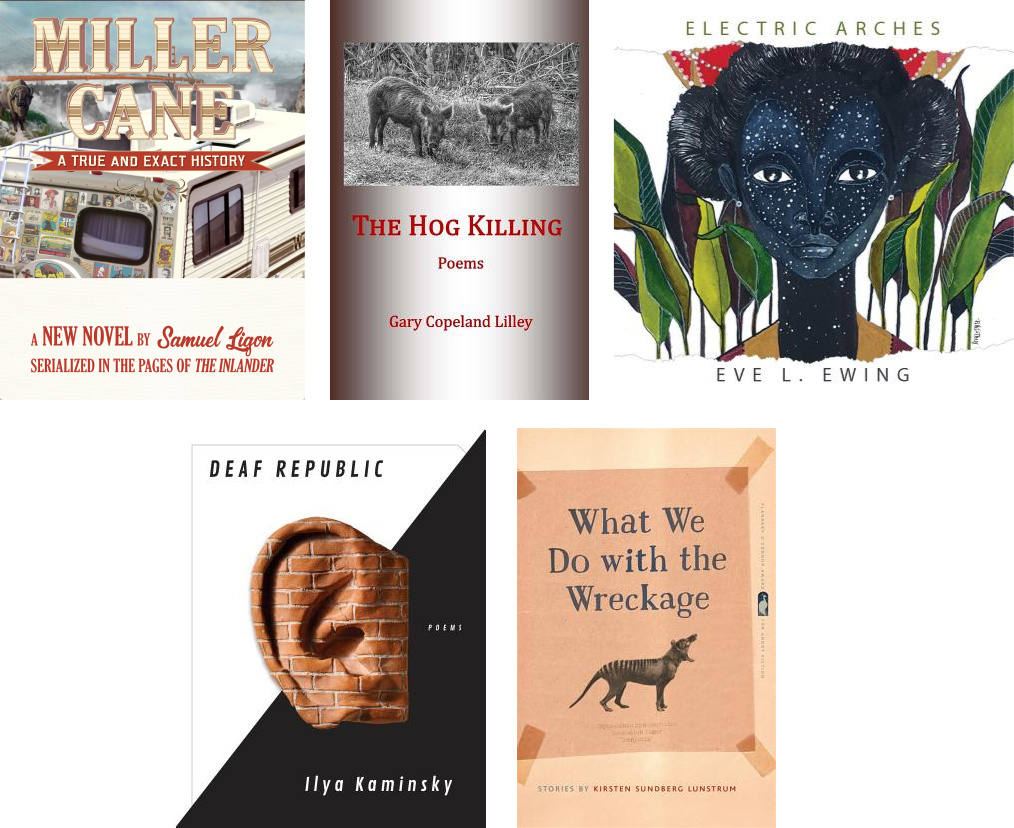

Sam Ligon’s Miller Cane: A True and Exact History, serialized in the Inlander, is the only reason I look forward to opening my email, where I get a weekly installment. Miller Cane lives the long con, and his marks are the victims of massacres. A fraudulent historian, Cane goes on the lam “to save the young daughter of the woman he loves, taking her with him on his roadshow across the worn-out heart of America, staying one step ahead of what’s after them.”

Miller Cane is a satire. Miller Cane is deadly serious. In this epic road trip novel, Ligon evokes the zeitgeist of our cultural obsessions with guns and healing while maintaining the pacing of a potboiler. His prose is unmistakable – taut, acerbic and driven by hope for a country whose rules he criticizes with the relentless fervor of a patriot.

Reading Miller Cane, I laugh so often I have to wonder why few writers make use of their wit to divine the pathos of our collective psyche. Among the many gifts of Miller Cane, aside from its gumshoe plunder of Pacific Northwest places and American history, are Ligon’s insights into parenting and the horrors of loving. Great lines abound.

The Inlander projects that Miller Cane will wrap up in 2019. Writing Miller Cane for weekly deadlines, reading it too on Spokane Public Radio, Ligon reaches for the legacy of that other great serialist, Charles Dickens. The only way out is through. Good luck, Sam.

What did you read last?

Lately, I’ve been flickering between two books of poems:

The Hog Killing by Gary Copeland Lilley, out on Blue Horse Press. Listen to him read “The Car is the Crucial Chariot to Rural Culture,” a poem that’s supple because his language is highly crafted and rooted in place and time. Gary’s poems sound like they come out perfect, a spontaneous rush of observation, thought and action, but his teaching approach is about rigor of vision and revision. I am honored to read with him and Paisley Rekdal on July 14 during the Centrum Port Townsend Writers’ Conference, where, in the afternoons, he’ll help folks resurrect dead poems while I’m teaching fiction.

I received scholar, cultural organizer and sociologist Eve Ewing’s Electric Arches as a gift from my friend Kristen Goessling, an assistant professor at Penn State Brandywine, where she teaches young people to activate their ideals with an artistic practice rooted in social justice and a collaborative pedagogy informed by her love of theory. I’ll read anything Goessling recommends.

After reciting Ewing’s “what I mean when I say I’m sharpening my oyster knife,” I ripped up this week’s syllabus for my Hugo House class and assigned Electric Arches, a mixed media book of poetry, essays and visual art from Haymarket Books. Based in Black reality, cherishing a future born from fierce imaginings for her community, Electric Arches is a true work of art.

What are you reading next?

I have deliberately delayed the gratification of finishing my advance reader’s copy of Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky, with thanks to Bill Carty and Seattle Arts & Lectures. Down hard with a cold, I just cracked Deaf Republic and was stunned into a pause by the first poem, “We Lived Happily During the War.” I am tempted to sample it here, in its entirety, as Kaminsky often does his favorites on Facebook (there is no better person to follow online for a running poetic commentary on our times, as elucidated by exquisitely paired works from his favorite writers). But I will content myself with “in the street of money in the city of money in the country of money.”

A book to savor, a book to devour. I battle my own proclivities to write this paragraph for you, rather than finishing Deaf Republic. Self implicating and expansive, something accusatory resides in his honesty. His litanies are revelations. I will never forget Kaminsky’s performance at the Centrum Port Townsend Writers’ Conference, where Ligon is artistic director. Kaminsky electrified the whole audience with urgent work that refuses our collective silence.

Part of SAL’s Poetry Series, Kaminsky will perform on Monday, April 1 at Broadway Performance Hall, Seattle Central Community College. 7:30 p.m. Deaf Republic comes out March 5 from Graywolf Press.

What book would you recommend most as a holiday gift?

Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum’s What We Do With The Wreckage, which won the University of Georgia’s Flannery O’Connor Award, is a slow burn. In this potent collection of short stories, Lunstrum maps the perseverance needed to survive the invisibilities of girlhood (and later, marriage and motherhood) to become women seen in our own right.

Amidst subtle scenes and intimate dialogue so real you wonder whether she takes notes at family dinners, Lunstrum breaks form to bring fable into daily life. Throughout, she delivers lyric insights with real authority. “I know that when I open my mouth next, I will speak like this – in gusts, with force. I will sound like fire moving through a forest…”

On Thursday, January 24th, from 7-8:30 p.m. at Hugo House, I will moderate a panel on the state of short fiction. Lunstrum will appear with Ramon Isao, Corinne Manning, Becky Mandelbaum, and E. Lily Yu.

November's 2018's Post-it note art from Instagram

Over on our Instagram page, we’re posting a weekly installation from Clare Johnson’s Post-it Note Project, a long running daily project. Here’s her wrap-up and statement from November's posts.

November's Theme: That November / Mixed Feelings

Thanksgiving and US elections stress me out. They are scary, and I don’t really want to talk about it. On the other hand, there’s my old love rainy weather. And sometimes a particular November turns out ok. These post-its are from a fateful November two years ago—yes, that November, one that very noticeably did not turn out ok. For me, that month started with a trip to the East Coast, staying with a college friend for a few days while we collaborated on what was both the most and least glamorous project ever. She and her partner provided an ACTUAL GUEST ROOM for me to stay in. The good fortune of having queer friends with guest rooms should never be underestimated, please remind me to delight in this memory more often ok? One wall was resplendent with old nautical prints; I don’t know why rooms on the other coast always feel darker to me than Seattle ones. In their bathroom, my musical-theater-loving friend had hung framed sheet music from eras past, including a 1910 song called “I’ve Got The Time, I’ve Got The Place—But It’s Hard To Find The Girl.” The bathroom is a great place to contemplate things, and I found myself contemplating the photo on the cover of that song. Crisply-pressed suit and tie; sweet smile; hat held politely in subtly gentle hand. Compelling in a way you’d only understand if you do. My friend explained the dapper young singer was professional male impersonator Hetty King, famed in English music halls of the early 1900s. Election day hit silently while I was on a train into New York, my ballot sent in long before the trip, bad news rolling through the city as the night went on, inescapable. (Inescapable, that is, unless you were the seemingly oblivious straight white couple on a first date next to me at that one empty-ish bar, forcing your loudly self-indulgent flirting down everyone’s throats, flaunting your privileged straight white happiness as the TV news anchors flailed and dread clamped down over my head and chest. You guys were awful.) When I got back to Seattle, there were so many people smiling at me. On the phone with another friend I shared my delighted confusion at these open, friendly looks around the neighborhood. Her theory was that I look gay—in the wake of the election, she posited, maybe these people were scrambling to reassure any visible minorities in their vicinity that they were sympathetic, safe, sorry even. There’s no way to know the answer. And then Thanksgiving—long days. Explaining anything feels wrong, because at the end of the day you don’t need to know my whole day, ever.

The Help Desk: Lord, give me the confidence of a lactating spider

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I work in a bookstore and I deal with self-published authors who come in to place their books on our shelves on consignment. Some of the authors are very polite and kind and understand that they're not my only client. But the pushiest authors I know, the ones who bug me incessantly and continually ask why I don't put their books on the counter at the front of the store, have the self-published books that don't even look like books — they're double-spaced, and the covers are garbage and they're printed on 8 1/2 by 11 paper. The back covers are riddled with errors, and the dialogue reads like it was written by an ESL class from Tokyo on its first day.

The most confident authors I've ever met are also the worst authors I've ever met. In your experience, is self-confidence a sign of bad writing?

Pat, Columbia City

Dear Pat,

Did you know that some spiders breastfeed their young? Imagine the body confidence it takes for a spider to look at a dairy cow, nature's milk-producing poster child, voluptuous udders refracted in each of its eight tiny eyes and think "Nice try but I can do better."

Spiders do not even have mammaries. What they lactate could better be described as protein venom, yet produce it they do. The reason? Confidence, willpower, and spite.

All artists are powered by a blend of confidence, willpower, and spite. It takes those three traits to take stock of the world – and the art already in it – and conclude an important point of view is missing: their own. This isn't a bad thing, but as you've discovered, when one trait outweighs the rest, the artist becomes insufferable.

Nature will take care of over-confident writers in time. Like over-confident spiders, their protein-to-venom ratio is screwy and they will find few volunteers willing to suckle at their teets, metaphorically speaking. This vicious cycle will continue until they are all venom, devoid of protein, and they find to their horror they have misspelled their own name on the cover of their own self-published book. On that day, they will quit art altogether and resume their career as a real estate agent/fly catcher while the watchers of the world, like you, quietly celebrate.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Martha Brockenbrough

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a portrait of a new author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Friday, December 7: Unpresidented Reading

Join Seattle author Martha Brockenbrough this Friday when she debuts Unpresidented, a biography of Donald Trump written with the YA crowd in mind.

University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.

Kissing Books: Something out of the ordinary

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

Holidays are points on the timeline where the ordinary world cracks open a little and something numinous filters through. In the Catholic calendar I was raised with the weeks leading up to Christmas are called Advent, which (like Lent in the spring) is officially, theologically different from the long stretch of green-robed months labeled Ordinary Time. Holidays were by definition extraordinary times.

Some holidays we fixate on more than others, as a culture. Some of those timeline cracks we take a narrative crowbar to, prying the opening wide to get more of the magic out. Christmas, for example, is always being worked at, even in tales that never breathe the name Jesus. There’s a kind of secular magic that turns up, though centering it on a Christian holiday still puts a great deal of pressure on people of other faiths. I think it’s telling that we classify Christmas stories as general fiction, even though they often feature clearly speculative elements. Mortals encounter ghosts or angels or spirits; magical objects change the course of a character’s life; supernatural agents work secretly for the betterment of all. A Christmas Carol is a time-travel book and a ghost story, though people look at you funny if you recommend it as such.

This year, heading into the darkest months, it feels like we need that magic more than usual. We need the oil to last longer than it‘s supposed to; we need ghosts to take gloomy mercy on our errors; we need a kindly supernatural hand to guide us toward a better, happier future. Maybe it’s that vast yearning that cracks open the world in the first place — you can’t make changes without first desiring change. And stories are how we come to understand what we want to be different. So many of those magical stories always seem to come back to very real, very human goodness: generosity, kindness, charity, hope, and love. It has to be more than coincidence.

There’s a scene in A Christmas Carol that almost never makes it into the adaptations: Marley, after confronting Scrooge, directs him to look out the window, where the London streets are teeming with guilty ghosts burdened by chains of greed and selfishness. They wail and weep among the homeless and hungry, and Dickens makes it clear: “The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had lost the power for ever.” The wish-fulfillment angle of this scene is not ghosts are real. It’s not even you can save yourself, chosen human. The wish-fulfillment is people can help one another in the real world.

Romance author Mary Buckell once said "if you’re writing literary fiction, you believe that people cannot change." Commercial fiction means you believe that people can change.” Half the time I believe this sentiment; half the time I want to challenge it to rapiers at dawn. But I do believe that a happy ending requires transformation. And transformations are hard. We humans are prone to entropy and sluggishness. We want to keep our compass steady, we want to stay where we’re comfortable, we want tomorrow to be predictable because then we know what to expect. We know, deep down, that to make a lasting change to habit or habitat requires more than the usual amount of motivation.

It requires, in fact, a little magic. Something out of the ordinary — an angel, a ghost, a magical Advent calendar in a TV movie. Something to help us do what we fear we’d never succeed at on our own. So we pick a date and pick up the crowbar — or a holiday story — and work to let a little more light shine through.

Recent Romances:

Thankful by Edie Bryant (contemporary f/bi f):

I must be honest: this book leaned a little too heavily on the misunderstandings for my taste. Don’t be an idiot! I was forced to yell silently, at more than one plot point. But allowances must be made for youth, and sometimes the perspective of thirty-seven years only weighs me down like the wettest of blankets. This book is the quintessential New Adult romance, which often feels as if the author and not only the characters are trying to find their voice. It is over-dramatic and prone to impulsive mistakes but also chock-full of what we Olds call potential — I have the oddest feeling that if I just leave this book alone to make its own choices it will grow up into something truly special.

It can’t. Because it’s a book, not a person. But I kind of wish it could.

Maybe it’s just the premise, which is so perfectly suited to my taste that it dwarfed every other objection. Heroine Danielle has had a strained relationship with her parents since leaving home (and coming out), so this year she decides to surprise them by showing up again on their doorstep in her hometown. Only they’ve moved. Out of state. Two years ago. Without telling her. And they wouldn’t have wanted her anyway, because their new condo is a bit too small for guests. It’s the absolute last straw in a long line of parental disinterest, and honestly when Danielle sat down to have a good cry on the porch it seemed like the most human thing she could have done.

But she isn’t crying long, because her former best friend Elise — who lives just across the street, with a houseful of happy extended family — finds her and demands she stay with them for the long holiday weekend. Danielle is nervous, because she always had a hopeless crush on her straight friend. Elise is nervous, because in the years since they drifted apart she’s come out as bisexual, but she’s never found anyone else who she loves as much as she loved Danielle. I’d have liked to have seen a few more scenes of our heroines interacting without the drama — the focused nature of novellas mean we’re in crisis mode most of the time, when I wanted to know how they would treat one another in, as it were, ordinary time. Holidays and family crises are states of heightened reality, which don’t always reflect someone’s daily state of being. But, on the whole, this sweet and earnest little f/f is doing okay, even if it hasn’t mastered adulting quite yet.

I’d met some great people with great qualities who, theoretically, I should have really been into. But I never was. There was never that chemistry that I desperately desired. I wanted to be with someone I loved. I wanted to be thrilled to wake up to someone in the morning and go to bed with them at night. I wanted happiness like I’d never felt it before.

A Wedding One Christmas by Therese Beharrie Carina Press: contemporary m/f):

This South African-set book is an absolute confection, but there’s a surprisingly rich and satisfying center beneath all the froth and frosting on top. Beharrie begins with a classic romance set-up: two strangers meet by chance at a wedding they have complicated feelings about. Angie is a romance writer still working through her grief about her father’s death years ago (just @ me next time, why don’t you) and Ezra is a newly heartbroken women’s studies professor (who never mansplains feminism to the heroine, thankfully) struggling to get perspective on the mistakes of relationships past. They are two people running headlong from their own pain and vulnerabilities, all of which get knotted up when they crash into one another. Like Christmas lights in a box in the garage. By the time they untangle all the separate strings, they’ve had time to start to heal and get their souls in order. And also experience the sheer, breathtaking horror conjured up by the phrase volunteer ad-libbed Nativity play.

Reader, it was appalling and hilarious and absolutely delicious.

Therese Beharrie’s buoyant voice moves like quicksilver, trading flirty banter for sharp, painful flashes of realization in an instant. It keeps the reader feeling comfortingly weightless even as she lands on truly profound questions: where is the line between independence and loneliness? Between wants and needs? How do you give yourself up to passion and generosity without sacrificing too much or leaving yourself hollow and empty? These are not problems quickly solved, as the book well knows. The story takes place in a single day but gives our hero and heroine plenty of scope for chemistry, for confrontation, and for communication. Like a stage play — or a ghostly holiday tale — where the emotional ground covered is far more extensive than the chronological space would appear to allow. Sure, it’s been one day in book time — but we’ve been there with these two for all of it. We know who they are by now, so it’s natural to believe they know each other well enough to fall a little bit in love. Sweet but not saccharine, heavy on the romance but super-light on the sex, this is one thoughtful holiday romance you won’t want to miss.

The real problem was that he wanted her. It was that plain, that simple. It had nothing to do with him going home. Or with what he’d face at home. It had everything to do with the falling. That after a day in her presence, he knew he was falling, and could only imagine what another day — a week, a month, a year — would do. He didn’t want to have to imagine. He wanted to live it. He didn’t want to say goodbye.

Tikka Chance on Me by Suleikha Snyder (self-published: contemporary m/f):

The power of the good girl/bad boy trope is this: the good girls are never as good as people think, and the bad boys are always secretly better than anyone gives them credit for. It’s about truth versus reputation; rumors, secrets, and hidden hopes all balled up together and heated up by conflict and chemistry.

That’s never been truer than in this sleek and perfect novella from Suleikha Snyder. Pinky Grover dropped out of grad school to help out when her mom got sick, and now slings plates in her family’s Indian restaurant, as though she never dreamed of traveling the world and studying unique cultures. Trucker Carlson was a fuck-up as a kid and now does worse as a member of the Eagles biker gang — a violent, gun-running, white supremacist outfit — but despite his poor taste in friends, Trucker can’t stay away from Mrs. Grover’s amazing samosas. Or from the daughter who serves them up. The two have no business hooking up, none at all. But months of silent eye-banging and one cheesy pickup line in a Walmart parking lot are all it takes to turn sparks into supernovas — and lord, did this book knock me down. Snyder has a way of taking two characters who are plenty interesting on their own, and making them sparkle even more brilliantly as a couple. Her sex scenes just feel like so much fun: banter and teasing and laughter, along with feelings and revelations and high-quality orgasms. It makes the breakneck pace of the romance completely plausible. “We can’t be in love this quickly,” the characters say, and the reader cries back that of course you can! Look at how good you are together!

It’s a roller coaster, with all the stomach drops and rushing adrenaline. We fall fast and hard and I for one wouldn’t have it any other way.

He wore his Eagles leathers — there was probably some kind of rule that he couldn’t take them off — but the faded T-shirt that hugged his chest sported Captain America’s shield. It seemed a little off-brand, given his choice of vocation and the company he kept.

Cinder Ella by S.T. Lynn (LoveLight Press: trans f/f):

Cinderella variants are my absolute catnip in romance — historical, fantasy, or contemporary, I like the classic shape as much as I like the twists, and I never seem to get tired of them no matter how many I read. The heart of the story is not about the prince, or not simply about the prince: it’s about a true and hopeful soul finding recognition of worth after having persevered through trials and suffering, and in spite of poverty and powerlessness. How could such a dream ever get old?

S.T. Lynn’s variant gives us a black trans heroine, making the question of recognition all the more vital. Ella has lost her mother and her father, and her social climbing stepmother insists on referring to her as Cole, her late father’s son, so Ella has to keep her true self carefully hidden unless she’s alone. Despite all the grief and heartache in her life, though, Ella is still a dreamer, still determined to find good where she can (the days she tends the gardens, pamphlets of designer dresses, her dog Lady). When she is invited to attend the ball and dance with the princess, it’s more than she ever dared hope for. This is a wide-open wish-fulfillment story, not subtle in the least and very YA-inflected, but Ella is so warmly charming that you stay with her even though you can see the strings moving, narratively speaking. The secondary characters are equally lovely, from the mischievous lady-in-waiting in love with the prince, to the small-town cheese maker and goatherd who helps Ella get back on her feet in the second act. It gave me serious nostalgia for all the semi-modern fairy-tale retellings I loved best growing up: Patricia Wrede’s Enchanted Forest Chronicles, M. M. Kaye’s The Ordinary Princess, the gorgeous film adaptation of Rogers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella starring Brandy as the lead. Sometimes you need to watch nice things happen to nice people, in spite of all the villains in the world.

Ella wasn’t sure if a woman could fall in love talking over dogs and gardening, two songs and a single kiss, but her heart was giving it a good try.

This Month’s Cult Classic

A Christmas Gone Perfectly Wrong by Cecilia Grant (self-published: historical m/f):

I love the Blackshear trilogy but until recently had let prequel novella A Christmas Gone Perfectly Wrong slip through the cracks. Turns out it’s my absolute favorite kind of Christmas story: a lonely, lovely misadventure with unexpected snow, stern souls learning to unbend, and finding warmth in places you least expect it. Eldest Blackshear sibling and general stick-in-the-mud Andrew has ventured out to the country to purchase a falcon for his soon-to-be-married sister. The falcons are trained by Baron Sharp and his daughter Lucy, who’s led a lonely if brilliantly educated life with her father for company — reading Hume, having philosophical debates, and training birds. Andrew puts the demands of family and duty above all else. Lucy yearns to know more of the world, but her father is set in his ways and doesn’t budge from his comfortable home. She has a chance to attend her first Christmas party in society, with people her own age and potential husbands — but to get there, she has to convince prim and prudish Andrew to throw propriety to the wind and drive her to her aunt’s house unchaperoned. It should be a short and simple trip, after which they will part as strangers forever.

Of course it all goes, as the title says, perfectly wrong.

There are more than a few romance authors whose status in the genre is partly due to sheer accumulation. Nora Roberts has written over two hundred titles and counting. The Romance Writers of America give their Centennial Award to members who’ve published one hundred books, and the list of names is both illustrious (shoutout to Brenda Jackson and Jayne Ann Krentz/Amanda Quick!) and surprisingly lengthy.

And then there’s Cecilia Grant.

There’s a much-mangled quote about the Velvet Underground: that they didn’t sell many records, but that every single person who bought one went out and started a band. Since her debut in 2012 Cecilia Grant has published three novels and a holiday novella — certainly not nothing, but quantifiably on the low end by romance’s ravenous standards. Yet those four stories inevitably crop up on best-of lists, in Twitter recommendation threads, and in conversations at conventions and Instagram feeds. People will occasionally ask each other if she’s still writing — because even nearly five years after her final novella appeared, they’re still hungry for more of her stories, more of her characters. She’s one of the rare authors who works both for longtime romance readers and for people brand new to the genre. If there is such a thing as a romance cult author, Cecilia Grant is it.

Trouble found him, in torrents that put the winter squall to shame.

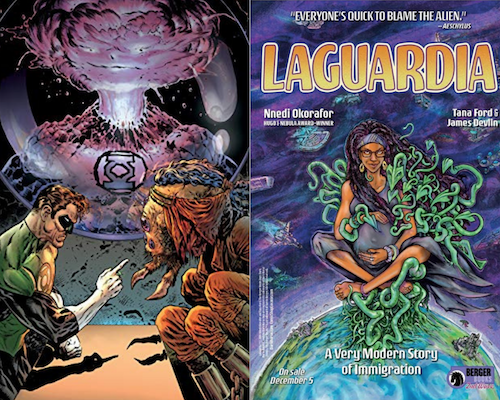

Thursday Comics Hangover: Illegal, aliens

Grant Morrison is two issues into a run on Green Lantern, and it's a glorious mix of Silver Age DC Comics and Heavy Metal magazine. The book is aggressively weird — one Green Lantern is a virus, another is a big, muscular body with an exploding volcano for a head — but it is at its heart a police story. There's an interrogation scene and a deathbed confession and all the tropes you'd find in a Law & Order episode, only with magic rings and bird-people.

Artist Liam Sharp is doing the work of his life on this book: in the past, his art has seemed better-suited for horror, but the weird sci-fi of Green Lantern is something else again. There's enough detail on every page to take out a reader's eye, and very few artists in general seem as uniquely skilled as Sharp at getting Morrison's enormous concepts down smoothly on paper.

Still, I have to admit to some uneasiness with the book. Green Lantern here is presented as a bit of a prick. (He calls himself a "bastard" at one point.) And his respect for the rights of criminals is, shall we say, less than robust. Morrison is hardly a rabid conservative, so the weird authoritarianism in Green Lantern is likely to be a setup for some kind of a revelation later on. It's surely the most beautiful book that DC is publishing right now, and there are high-concept ideas on every single page of the book, but this isn't the time to elevate a hardline law and order agenda in a comic book.

This week also saw the first issue of a new comic series written by sci-fi writer Nnedi Okorafor. Like Green Lantern, Laguardia features bizarre aliens and high-concept sci-fi throughout. But unlike Green Lantern, Laguardia is interested in the personal struggle against law enforcement.

Beautifully illustrated by Tana Ford, Laguardia is the story of a very pregnant Nigerian woman named Future who flies in to the Laguardia International and Interplanetary Airport ("the only airport with interplanetary travel services in North America.") There's a complex and thoughtless customs process to navigate, and the airport is teeming with aliens making their way to and fro: small, green germlike creatures, a man with a carrot for a head. They're coming to America.

Laguardia is a futuristic story about one of the oldest human concepts: borders, and what they do to us. Future has a plan to upturn America's anti-alien culture (it involves an alien named Letme Live) and she's not afraid to break a few laws to do it. Between Future and the Green Lantern, I know where my loyalties lie.

Rebecca Solnit calls us by our true names, but sometimes we can't hear her

Rebecca Solnit's book of essays, Call Them by Their True Names, left me feeling depressed. It's not that Solnit is a depressing writer — in fact, the book ends on a series of hopeful grace notes. And it's not even that Solnit directs her considerable intelligence toward the very real problems of America in 2018 — the harassment and abuse of women, the president's aliterate war on rationality, the battle lines of power being drawn in our gentrifying cities.

No, for me the issue is that Solnit is such a brilliant writer, and that she writes with such surety, that as soon as I set Names aside and open my Twitter feed, the world feels murky and grey in comparison. Arguments are less sharp, reality seems confusing in its moral complications. It's like going from a high-definition television to a grainy black-and-white set with a clothes-hanger antenna.

We had plenty to discuss at last night's Reading Through It Book Club. Solnit seems to only write about the most pressing issues of our time, and the essays in Names are so immediate that the ink on the pages practically feels wet. She finds the connections between all the fault lines in our culture, finding the surprising links between #MeToo and Trump's election, gentrification and police shootings.

I mean, this is pretty convincing:

Trump is patriarchy unbuttoned, paunchy, in a baggy suit, with his hair oozing and his lips flapping and his face squinching into clownish expressions of mockery and rage and self-congratulation.

"Patriarchy unbuttoned" is a pretty great turn of phrase for the current moment, with Kavanaugh bellowing and Lindsay Graham shrieking and basement warriors everywhere whining about men's rights. It's two words that distill everything, a pure display of Solnit's power.

Last night's book club ended with a discussion of Solnit's wrenching account of gentrification in San Francisco and how it relates to Seattle. The next few months will see candidates from across the political spectrum running for seven neighborhood seats on Seattle's City Council. Those campaigns are likely to incite a volatile conversation about what we want the city to be, and what our responsibility is to each other. I have a sneaking suspicion that when all is said and done, Seattle will not live up to Solnit's exacting moral standards.

Bookmark this link and check back on it in a few years for a good dark laugh.

Big book distributor to be bought by slightly larger book distributor?

Holy shit: this, from Publishers Weekly, is terrible news:

The Ingram Content Group has made a tentative offer to buy the retail wholesaling operation of Baker & Taylor, and the Federal Trade Commission has launched what it is calling “very preliminary investigation” of the proposed deal, sources told PW. The Ingram bid was made about a month ago, sources said.

If you've never worked in a bookstore this might sound like inside baseball. But if you shop at independent bookstores, this is something that could very well affect you. If the largest book distributor in the country buys the second-largest book distributor in the country, bookstores will likely be facing a monopoly situation — one in which Ingram can set the terms however they like.

It's true that bookstores will still be able to order titles directly from the publisher, but distributors are an important part of the book business — they're more expensive to buy from than the publishers, but they're faster and more efficient. If there's less competition in the distribution field, however, the incentive to be fast and efficient goes away.

This might sound like scaremongering to you, but there's already a clear example of what happens to a business when there's only one distributor: comics shops around the country get their product from the only comics distributor in the business, Diamond. And I don't know if you've heard lately, but comics retail is...not doing great.

The American Booksellers Association should be using the entirety of its power to fight this potential deal. Ingram buying Baker & Taylor will not benefit independent booksellers in the least — in fact, it is guaranteed to harm them. Please contact the ABA and tell them to take up this charge. We can't trust the Trump Administration to do the right thing and block this monopoly in the making.

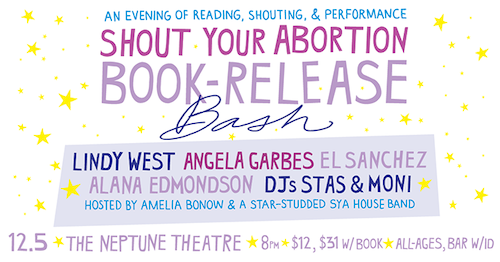

"I am offering you a 1,000,000% guarantee that what will transpire at the Neptune tonight will make you feel alive and free."

As Martin told you in this week's Whatcha Reading column, tonight is the launch party for the Shout Your Abortion anthology at the Neptune Theater (get your tickets here.) We talked with SYA founder Amelia Bonow about the creation of the anthology and why — even though it's cold and dark and generally Northwest wintry outside — tonight's event is worth your time and attention.

Why was it important for you to make a SYA book? Why not a podcast or a documentary for your first major media document?

This book is our first attempt at a creating a snapshot of the movement, and in some ways, that felt impossible. One of the main things that SYA wants to communicate is that there is no single abortion narrative. Making a book that communicates that is sort of a catch twenty-two because no matter what, you’re going to select and edit a finite number of stories and your curation will create an arc of some kind whether you want to or not.

However, after the 2016 election I felt really strongly that we needed a practical, tangible tool that could communicate what SYA is doing and why, and help people find their way into the movement. In some ways, books are more accessible than the vast majority of mediums. They are infinitely sharable, they are un-hackable, they are something which people can encounter by accident. On that point, another reason I wanted to make this book is that it’s intended to be a tool for abortion clinics. We got a grant from Abortion Conversation Projects and we will be sending this book to hundreds of clinics for their waiting and recovery rooms, so thousands of people will flip through this book before or after they have their abortions. I honestly believe that simply encountering some positive representation in that moment will allow many people to have a profoundly healthier abortion experience. It’s a really beautiful thing to think that this book could disrupt the expectation of silence and shame for someone before it has a chance to get totally ingrained.

While I know you and Emily Nokes have worked on zines together, I believe this is your first book project, correct. Can you talk about the process of making the book, and what you learned while putting it together?

It was really special to make this book with Emily, because she one of my best friends and she also happens to be one of the most talented people I’ve ever met. She also lives next door to me, which means we could literally air drop gigantic files back and forth without wearing pants.

Emily and I worked together in a way that was everything I love about women: it was a collaborative process with a lot of mutual trust and zero ego. It was very intuitive and symbiotic and wavy and we factored in one another’s menstrual cycles into our work plan and I am not joking. Why wouldn’t we? Also, making a book is wildly, unfathomably stressful, especially when you are making an abortion book that has upwards of 100 contributors. The fact that we were able to get through such a grueling process and feel totally supported and respected by each other is an affirmation of everything this book is about! Women are the only people who have ever held me down like that. I guess if anything, making this book confirmed my feeling that I really don’t want to work with cis men anymore.

It's a very interesting format — magazine-y in some places, a literary anthology in other places. Did you have any books that you looked to as inspiration for the anthology?

Emily and I both spent a lot of time thumbing through books and found inspiration here and there but I don’t think we really found anything like the book we wanted to make—I feel pretty confident saying that nothing like this has ever existed before.

Seattleites in December are prone to heading home in the pitch dark after work, putting on some comfy sweatpants, and crawling inside their couches for some hibernation. What's your pitch to someone who wants to fight that nesting urge and come out to the show tonight?

You can wear leggings to the Neptune! Wear your couch! Winter insularity is totally reasonable because it’s really hard to know if something is going to be worth it. Like, is this band going to be as good as my couch? In this particular case, I am offering you a 1,000,000% guarantee that what will transpire at the Neptune tonight will make you feel alive and free. And we all need to feel that way as much as we possibly can these days.

Book News Roundup: Sign up for Clarion West's summer workshop now!

Are you a sci-fi writer? If so, you need to apply for Clarion West's 2019 summer workshop, which is a six-week intensive learning session for writers of science fiction and fantasy. This year has an impressive list of teachers, including Ann Leckie, author of Ancillary Justice.

At Crosscut, Brangien Davis reports that Seattle has the most Instagrammable public library in the world.

Speaking of Crosscut, that's where Knute Berger wrote a piece about his experience interviewing Bob Woodward about his book Fear onstage at the Paramount Theater this week. I wasn't crazy about Fear, but I'm thrilled that lots of people are still willing to pack a theater to listen to a journalist talk about his work.

The excellent journal A Public Space is getting into the book publishing business. They'll put out four books a year to start.

Here's a very good overview of the plagiarism scandal that dominated poetry Twitter over the weekend.

This tweet is the most disgusting "let them eat cake" employer moment I've seen in a while:

- Speaking of Amazon, this piece about New York City Bookstore The Strand has a magnificent quote about why the owners are not interested in landmark status:

“The richest man in America, who’s a direct competitor, has just been handed $3 billion in subsidies. I’m not asking for money or a tax rebate,” Ms. Wyden said. “Just leave me alone.”