If you're looking for something to read this afternoon, I recommend this wonderful deep-dive interview with Seattle cartoonist Tatiana Gill.

What big teeth you have, Gramma

Published June 19, 2018, at 11:58am

This Saturday, small independent publisher Gramma Poetry re-launches with a huge reading, a new literary magazine, and new leadership. But what does it mean to be a Gramma title?

給電腦的情書 (Love Letter to a Computer)

滿以為很瞭解你因為

跟你這樣朝夕相對呼吸相連

已經三年零十個月了

我的姓名、性別、履歷和理想

通通分類存檔並且定期更新

任滑鼠隨時進入或下載

你都給我無限寬容或寬頻

遊歷於上下合縱左右連橫的空間

你輕盈的樂聲總吻合我跳躍的舞步

跳出情感互動的一片藍幕

(藍幕的下角有青草

上角有小花和恐龍)

原以為可以和你白頭到老永結同心

一如酒樓菜牌上紅底金字的承諾

但原來你也有背叛的時刻

偷偷跟旁人搭訕然後搭線而且

還很小心地讓我讀到你們的情話與暗碼

於是我開始猜疑你花亂而閃爍的面容

暴力敲打鍵盤上每個凹凸可疑的指模

或用苦纏的動作拉扯已經鬆脫的電線

期求你不再板起冷漠的凝視

對我輸入的話語不聞不問

或隨意亂碼顧左右而言他

甚至突然自動關機從此不再跟我會面

是的 沒有受過專業訓練的我

並不能熟練地操作戀愛的各種程式

——密碼錯誤,請重新輸入

(你說過會一輩子待我好

無論我們是什麼但那

「什麼」到底是什麼?)

——程式偏差,無法存檔

(我們曾經一起吃飯的

那間茶餐廳因為

樓宇遷拆而倒閉了)

——網頁無法啟動,請稍候

(當我打算在你的電子郵箱留下

口訊時你剛巧致電到我的傳真機

彼此的網絡因為佔線而阻斷)

——線路繁忙,請按Refresh 按下去突然一屋暗燈

牆壁發出陣陣燒焦的惡臭

當神經線錯接電腦系統時才發現

自己原來是個電腦與愛情白痴

——「懂得愛戀自己的人才得享永生!」

上帝(如果有的話)也禁不住竊笑然後搖頭嘆息

為我這句史無前例的盟誓translation

I thought I knew you because

all night and day our breath mingles together

for three years and ten months

my name, gender, resumé, and ideas

have been classified as files and updated at the set time

entered or downloaded according to the mouse

you’ve given me unlimited broadmindedness and broadband

to traverse the up/down left/right horizontal/vertical space

your lovely musical voice accompanies my dancing

your blue screen quits out of emotional interactions

(there’s grass in the lower corner of the screen

in the upper corner there are tiny flowers and dinosaurs)

I used to think we would grow old together

like in the promises of a red and gold menu

but you’ve had your moments of betrayal

secretly conversing with others and making contacts

but also carefully letting me read your intimate notes and codes

until I began to suspect your unruly flickering face

pounding the keyboard with all my suspicious fingers

or bitterly pulling on the loose cords

I pray you won’t ever stare blankly at me again

ignoring every word I type

or casually change the subject to code

until you suddenly shut down and refuse to see me

yes, since I have no special training

I can’t just skillfully make various attachments

——Wrong password, please try again

(you said you would wait for me your whole life

no matter what but what does that

“what” really mean?)

——ERROR, your file has not been saved

(we used to eat together

but that café closed

when the building was torn down)

——This page cannot be opened, please try again in a moment

(just as I planned to send you an email

you sent a message to my fax machine

and with the line busy, neither one could go through)

——The line is currently busy, please refresh the page

and when I refresh it things suddenly go dark

the wall lets off an acrid stench of burning

and when I mistakenly connect my nerves to the system I realize

I was an idiot when it came to computers and love

——“Only those who understand love will live forever!”

even God (if there is) has to snicker and sigh

over this unprecedented oath of alliance.

Read a sample from the dark thriller Down the Brink

Lisa von Biela is a local author with professional experience in both the law and IT. That gives her writing bite: You can't put her books down, not just because they're great storytelling (and a fabulous summer read, if dark fiction is your jam), but because the thrills are just a little too close to home. Check out this sample from Down the Brink, and you'll see what we mean.

Sponsors like Lisa von Biela not only bring great events and new releases to your attention, they make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? If you have a book, event, or opportunity you’d like to get in front of our readers, find out more, or check available dates and reserve a spot.

2017 VIDA Count numbers released

If you're a fan of the literary arts, or if you're a writer, you should be paying close attention to the VIDA Count. Every year, the nonprofit feminist organization VIDA "highlights gender imbalances in publishing by tallying genre, book reviewers, books reviewed, and journalistic bylines to offer an accurate assessment of the publishing world."

This year's VIDA count examines the contributor demographics of outlets including Harper's, Granta, The Paris Review, and many more. They've presented a number of graphs showing representation of gender, race, identity, and disability arranged by outlet. This year, the The New York Review of Books and The Believer both performed abysmally in terms of gender representation. NYRB has "the most pronounced gender disparity of 2017’s VIDA Count, with only 23.3% of published writers who are women" and...

...The Believer performed with the most disappointing figures, publishing a scant 33% women, and no nonbinary individuals. No books authored by women or nonbinary writers were reviewed. 71% of writers given the mic to conduct an interview were men, and 57% of those who were interviewed were also men. It should be noted that in 2015, every single author of a book reviewed, as well as every single reviewer at The Believer were men, as well.

The point of the VIDA Count is not to shame specific outlets, but to let them know that someone is watching, and counting, and keeping track of representation. Often, just knowing that someone is paying attention to numbers like this can be enough to change the choices that a publication makes.

Artist Trust describes their annual fellowships as "an unrestricted grant program that awards $7,500 to practicing professional artists of exceptional talent and ability." Today, they announced 16 winners across disciplines including visual art, music, and performance. I'll let the Seattle Review of Visual Art and the Seattle Review of Music cover the other winners, but here are the literary fellowship winners:

Cartoonist Tessa Hulls also received a multidisciplinary award. Congratulations to all the winners! You all deserve way more than $7,500 dollars, but you probably agree that $7,500 is a pretty nice start.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from June 18th - June 24th

Monday, June 18: A Reading for Refugees

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Intrigue Chocolate, 1520 15th Ave, 945-3277, https://www.intriguechocolate.com, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, June 19: Juneteenth Storytelling Event

This is a storytelling celebration of Juneteenth with local Black musicians, comedians, and other storytellers sharing tales of freedom. Related: Why the fuck isn't Juneteenth a national holiday? Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, 104 17th Ave S, 684-4757, http://langstoninstitute.org, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, June 20: WordsWest Kids' Night

This special children's-themed edition of the popular West Seattle reading series brings Suzanne Selfors, author of Spirit Riding Free: Lucky and the Mustangs of Miradero (which is now a Netflix series) and Dana Claire Simpson, who creates the webcomic Phoebe and Her Unicorn. C&P Coffee Co., 5612 California Ave SW, http://wordswestliterary.weebly.com, 6 pm, free.Thursday, June 21: Roxane Gay

Last week, I reviewed a timely reissue of Roxane Gay's debut short story collection. This week, Gay is in town with Not That Bad, an anthology of women's stories in these #MeToo-y times. No matter what book you leave this reading with, you'll be satisfied. Gay is one of our most important writers. University Temple United Methodist Church, 1415 NE 43rd St, 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, $16.99 - $26.99.

Friday, June 22: Alexandra Mattraw and Amber Nelson

Berkeley poet Alexandra Mattraw celebrates the publication of her first book, small siren, with Seattle poet Amber Nelson, who used to be a publisher but is now happily doing more readings of her own work more frequently around town. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.Saturday, June 23: Locus Awards Weekend

Locus Magazine is celebrating its 50th anniversary with a three-day sci-fi orgy including a banquet, a bunch of classes for aspiring sci-fi writers, appearances from Seattle writers like Greg Bear and Nisi Shawl, and a big damn awards ceremony! Best Western Executive Inn, 200 Taylor Avenue N, https://locusmag.com/2018-locus-awards-weekend/, Fri-Sun, $65.Sunday, June 24: 100 Things Sounders Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die Reading

Seattle Times writer Geoff Baker presents a new book full of information about Seattle's soccer team, The Sounders. It also has the promise of death in the title, but it's probably not a super-morbid read or anything like that. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: A Reading for Refugees

Guess how many refugees from Iraq and Syria the United States has accepted this year. Just pick a number that sounds right to you.

Did your number have four digits? Three? If so, you expect waaaaayyy too much of this country. The correct answer, according to the organizers of this reading, is 29 Iraqi refugees and 11 Syrian refugees. That's embarrassing. Jordan, by contrast — a nation of 9.5 million people — has taken in some 700,000 refugees from those countries.

The truth is that America sucks at welcoming people in need. Tonight, a new dessert shop on Capitol Hill is hosting a fundraiser reading for the Collateral Repair Project, which "provides holistic assistance to vulnerable refugees living in Amman, Jordan" using "basic-needs and trauma-relief support" to help them through traumatic times.

The readers at this event include Judy Oldfield, Matt Muth, Richard Chiem, Jakeva Phillips, Katie Lee Ellison, and Kamilla Kafiyeva. All will be reading work on displacement and war and heartbreak and the act of being a refugee. Intrigue Chocolate, which is hosting the reading, will donate a portion of the evening's proceeds to benefit the Collateral Repair Project, in order to help a nation that is actually doing its part to be a good global citizen. Unlike the United States of America, which ought to be ashamed of itself.

Intrigue Chocolate, 1520 15th Ave, 945-3277, https://www.intriguechocolate.com, 7 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for June 17, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

My Romantic Life

This, by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, is a glass bullet of a piece that’ll leave shards all through you regardless of where it explodes.

The second time I did porn it was with Zee, when we were boyfriends, and I’d just remembered I was sexually abused, so I was taking a break from sex, but then Zee called me to do the video because his costar showed up too tweaked out — I did it because I needed the money, but then Zee got upset when I couldn’t come, and I felt like a broken toy. Which is how I’d felt with my father. When I walked out into the sun after that first video shoot I just felt totally lost, like I didn’t even know where I was and why was it so hot out, maybe that’s why I felt so dazed.

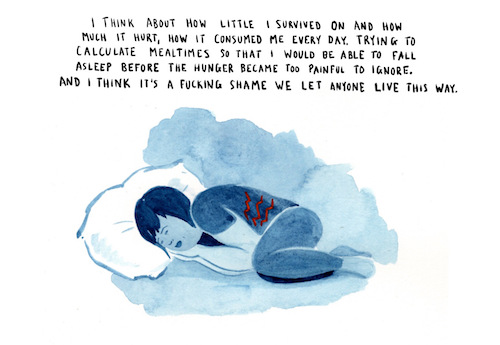

The Difference Between Being Broke and Being Poor

Erynn Brook (words) and Emily Flake (pictures) have made a softly lacerating visual essay on the distinction between not-having-money-right-now and not-having-money-period. Relevant, unfortunately, to Seattle’s interests.

What If I'm Just a Minor Writer?

Karl Taro Greenfeld had my sympathies from his first line: "I’m not who I was supposed to be." Yet: there are dozens of books by "minor" writers that I read over and over, because they help me survive. Do we all dream of becoming “great” writers (those of us who dream of becoming writers at all)? What’s wrong with just writing well? Or even — just writing?

I dreamed of writing novels that transcended time, that perhaps would someday convince a boy or girl that he or she should become a writer. Like a mother spider who births a thousand spiderlings for only one to survive to motherhood herself, perhaps this is how writers as a species survive. We all dream the same dream, to become important writers. Most of us never achieve it.

A Company Built on a Bluff

Courtesy of Reeves Wiedeman, a crazy-fascinating look at how Vice co-founder Shane Smith sold a particularly bro-centric idea of cool to round after round of investors, transforming an underdog counterculture paper into a media empire. Some of these stories are already well known (like the “non-traditional workplace agreement” and the New York Times investigation into sexual misconduct), but this pulls it all together, and says as much about what media consumption, creation, and investment are becoming as it does about Vice itself.

On the morning of the Intel meeting, Vice employees were instructed to get to the office early, to bring friends with laptops to circulate in and out of the new space, and to “be yourselves, but 40 percent less yourselves,” which meant looking like the hip 20-somethings they were but in a way that wouldn’t scare off a marketing executive. A few employees put on a photo shoot in a ground-floor studio as the Intel executives walked by. “Shane’s strategy was, ‘I’m not gonna tell them we own the studio, but I’m not gonna tell them we don’t,’ ” one former employee says. That night, Smith took the marketers to dinner, then to a bar where Vice employees had been told to assemble for a party. When Smith arrived, just ahead of the Intel employees, he walked up behind multiple Vice employees and whispered into their ears, “Dance.”

Punching the Clock

We’ve all worked a bullshit job — seemingly or truly pointless labor created to fill paid hours. Here’s David Graeber on why the already noxious state of affairs in which another person owns one’s time becomes so much worse when they use it badly.

Most societies throughout history would never have imagined that a person’s time could belong to his employer. But today it is considered perfectly natural for free citizens of democratic countries to rent out a third or more of their day. “I’m not paying you to lounge around,” reprimands the modern boss, with the outrage of a man who feels he’s being robbed. How did we get here?

Whatcha Reading, Martin McClellan?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Martin McClellan is the co-founder of this site, and when we started this column, we thought featuring the people who work on the site once in a blue moon might be a nice idea (see what associate editor Dawn McCarra Bass was reading a few months ago). You already know mostly what we read by reading our reviews, but in particular Martin (who is writing this in third person, uncomfortably), reviews much less frequently than Paul (although more frequently than Dawn), so there are many books he doesn't get a chance to talk about.

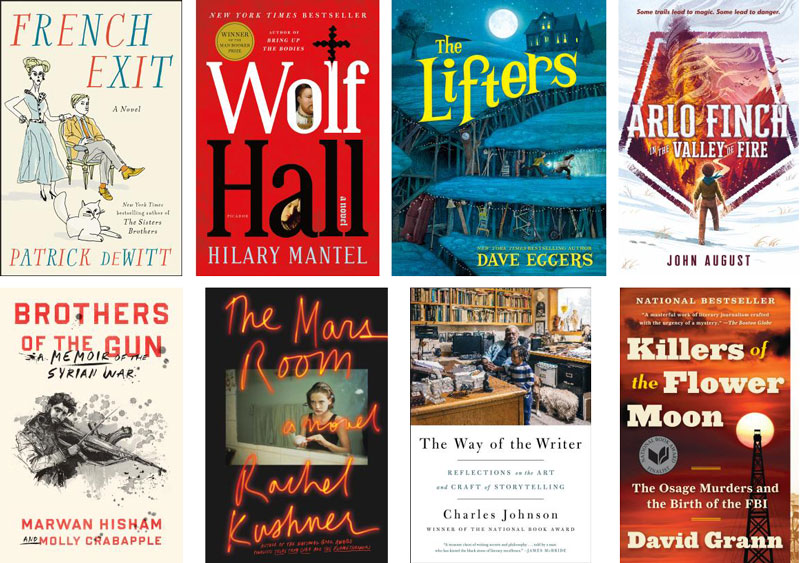

What are you reading now?

I'm in the middle of Patrick deWitt's upcoming French Exit. I really liked The Sisters Brothers, and deWitt is the kind of writer who can pull off stories from radically different genres with what seems like little effort. I can't even imagine how much work that takes.

I'm also listening to the audiobook of Wolf Hall. I wanted to watch the miniseries, but knowing how marvelous a writer Hilary Mantel is, I didn't want to deny myself the pleasure of her prose and storytelling. But, I was feeling a little bummed that I couldn't watch along while I read, until I remembered that, duh, this is the British Reformation and, duh, I know the story pretty well. When I realized that, I've been gleefully watching episodes as I listen, more-or-less in parallel (not everything happens in the same order in both mediums). I just hope everything turns out okay for that dynamic, engaging Boleyn woman.

What did you read last?

I just finished reading Dave Eggers' The Lifters to my son, and I absolutely love this book. The last book we read together was John August's Arlo Finch in the Valley of Fire, and although we both enjoyed it, I think my son liked it a lot more than I did. For me, August (who I admire so much, and have learned so much from, in his blogging and giving back to the screenwriting community on his podcast Scriptnotes) laid his book out sensibly, and with some interesting bits, but the overall feel was like a soup you just made, where the flavors haven't meshed yet.

Eggers, in contrast, lives in his sentences. They're lovely, and his turn of phrase is disarmingly good and charming — which is a joy, since you can sometimes feel him appropriately holding back his more whimsical nature in his non-fiction, but also even in a book like The Circle. It's always seemed that he wanted to deliberately move out of the looming shadow of the deep ironic humor of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genious by paring his craft down to a simple, reliable kit of tools. Which is not to say his work suffers for it — I generally always come away from an Eggers read feeling better off than when I started.

But The Lifters is something special. He has fun with it, and it shows in the language. There is whimsy and irony, and some pratfalls so well played you can hear the snare hit when you turn the page. That's all nice, but The Lifters doesn't succeed because of that. It succeeds because it's got a message embedded in a slowly-revealed heart-rending metaphor, and the message is a really good one that the story illustrates, but doesn't belabor or become beholden to. I would recommend it as a read, even for non-middle-grade readers. It's the most fun I've had reading a book in years.

I think August he'll need to write a few more novels before they come alive in your hands. Since this is the first in an Arlo Finch series, perhaps he will. In the meantime, The Lifters is self contained (no setup for an obvious sequel), and will remind you more of the kind of mid-century books for kids that were such a joy to read, and were obviously written by brilliant writers who were palpably enjoying themselves so much when they wrote that their enthusiasm infects the page even when the story turns sad.

What are you reading next?

I know that you, reader, have an enviable to-read pile. This is the curse of those who love to read. But, have you seen our Mail Call? The to-read pile of a person involved with a review site is towering, which goes to show optimism is never tied to any sense of realism. But, there are a few standouts that have come in the mail I'm very interested in, and also I picked up some titles at local Indy bookstores recently.

I'm really excited to get to Rachel Kushner's new book The Mars Room. I enjoyed Telex from Cuba, but I absolutely adored The Flamethrowers, with its deep interrogation of being a woman inside of men's spaces, and a protagonist fighting so hard to claim her identity and make her mark. It's one of those books that flew into me hard and left wing prints on my chest, although what I'm left with are fluttering impressions more than a comprehensive memory of the plot points. I'd be into revisiting that as well, but dammit, adding books I've already read back on the to-read pile feels like cheating myself out of a totally new book.

I went and saw Molly Crapapple at the Elliott Bay Book Company, and her co-author Marwan Hisham Skyped in from Turkey. Their book Brothers of the Gun is a biographical telling of Hisham's witnessing ISIS taking over his town in Syria, and clandestinely reporting on them. The talk was fascinating, and the book seems so compelling — they collaborated both on the text, and the images, which Crabapple drew, and Hisham art directed (eighty-two of them, the same amount as Goya's The Disasters of War). I'm reserving this when my heart can take it.

Charles Johnson's The Way of the Writer is on my stack. I have a weakness for writing inspiration or instruction books, especially ones from great writers. The format is the best kind of self-help, married to the kind of view into a writers mind and process that, because of the solitary nature of writing, is rarely granted. I love the intimacy of that glimpse on how another mind approaches writing, and Johnson's writing is so clear and bright, and his history of instruction and teaching so long, that I'm sure this one will be a standout on my little bookcase of like titles.

And finally, our Reading Through It book club is reading Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann, so I'll definitely finish that one by the 5th of July, when we meet at Third Place Books in Seward Park. This book is supposed to be very compelling, and the kind of thing you'll swallow in a few big gulps. If you've read it, or it's on your list, come join us in July for our discussion — it's a friendly group, and we always have a lively talk.

The Help Desk: Seattle is a toxic pit of hate and failure right now. Can books help?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Between the soaring real estate prices, the changing character of the city, and the NIMBYs trying to criminalize homelessness, I’m feeling very disappointed in Seattle, and I’m wondering what I can do.

Is there a way to use bookishness as a weapon for good in the battle to make Seattle an affordable, livable place again?

Deborah, Ravenna

Dear Deborah,

Did you know it is tick season? And boy, what a season we're having! Unfortunately, books can't make Seattle affordable any more than sprinkling a sack of thirsty ticks in Jeff Bezos's bed can improve my credit score. Building equitable cities is not job of books; it is the job of people. What books can do is improve the quality of our society by introducing people to experiences and perspectives that are far outside their own, essentially turning reading into an exercise in empathy and patience. It's embarrassing that the richest man in the world – a man who built a near-trillion-dollar empire on selling books – has neither of those qualities himself, and even more embarrassing that Seattle's civic leaders lack the sack of ticks to hold him and his miserly company accountable to the community in which they both thrive.

Some day, when I am elected to human office on an eight-legged platform, misers like Jeff Bezos who prosper from society without contributing meaningfully in return will be banished to the sewers (or forests!) where they will be used sparingly by their spider (or tick!) captors as a food source – not drained completely, certainly not killed, simply juiced for an appropriate amount of time so they can fully appreciate how it feels to be helpless and without resources.

But that will probably take a few years – at least until the Great Spider-Tick Peace Talks of 2018 resolve themselves. In the meantime, what you can do is this: Support Seattle's public libraries, which make reading accessible for everyone and are an especially vital resource for the poor and homeless. You can also contact the homeless shelter or tent city closest to your neighborhood and ask if you can bring by some supplies, including books (for instance, Mary's Place is in need of current children's books). This lets your homeless neighbors – because they are still your neighbors, whether they have homes or not – know that there is support for them in their community.

Kisses,

Cienna

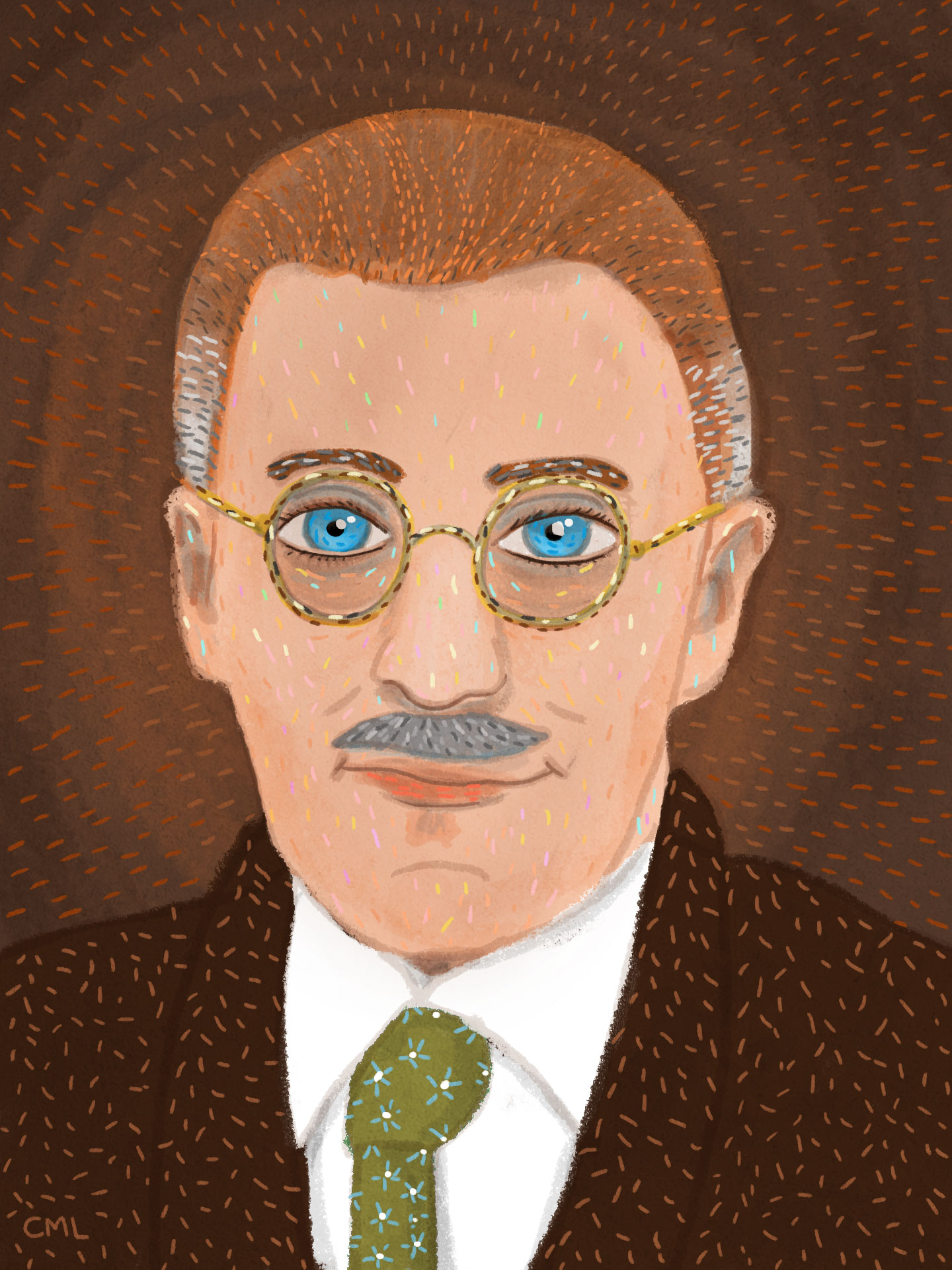

Portrait Gallery: James Joyce

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Saturday, June 16: Bloomsday Staged Reading

It’s Bloomsday again, so get your Joyce on with this reading from Ulysses. If you’re someone who tried and failed to enjoy Ulysses in print, hearing it read aloud might just be the key that unlocks the book for you.

Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 2:30 pm, free.

Future Alternative Past: Kicking it around

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

And now the sports

The late, great Gardner Dozois inscribed my copy of Future Sports (one of the dozens of SFFH anthologies he edited and co-edited) thusly: “For Nisi, who would make a great future sport herself!” I miss him so much. But yes, this was a joke, because I have always been such a nonstarter. My father’s sarcastic nickname for me as a teenager was “Coordinated.”

The stories in Future Sports include brief but pointed examinations of all the ways chance and athleticism will change the world to come, and be changed by it. Nerds like you and me (Michael Swanwick and Howard Waldrop, to name a couple) contributed tales of boxing zombies — okay, “postanthropic biological resources” — and other skiffy twists on the subject. And that sensawunda thing SFFH is so famed for? Kim Stanley Robinson’s narrator rhapsodizes about the beauty of playing baseball on Mars: “the diamond about covered the entire visible world.”

Michael Bishop’s classic Brittle Innings, another SFFH baseball yarn, takes place back on Earth, in the mid-20th-century Southern US. But one of its main characters seems to have been assembled in a lab rather than born.

Turning to other sports and more recent publications, we’re treated to the awesomeness of 17776, or What Football Will Look Like in the Future, which depicts a mutating array of structures, rules, and fields for the game, all evolved in response to humanity suddenly becoming immortal and invulnerable. The viewpoint characters are three robots, interplanetary probes battered into sentience by repeated exposure to Earth-based broadcasts. Their story is told via a wild mix of media: comics-like text balloons, GIFs, still images, and videos. As the person whose Facebook post first exposed me to 17776 wrote, “What did I just see?”

Henry Lien’s Middle Grade novel Peasprout Chen: Future Legend of Skate and Sword doesn’t just posit the sfnal time-warping of one sport. It mashes up competitive ice skating with martial arts to create a new one: “Wu Liu.” And The Galaxy Game by Karen Lord centers on an intrastellar pastime called “wallrunning,” a parkour-ish team sport enlivened by unpredictable changes in the course’s artificial gravity.

Further examples of jock-centric SFFH are out there, I’m sure, even excluding the plethora of stories focusing on board games and RPGs and some folks’ nostalgia for video arcades. Stretching the definition of sports to include those would mean I’d get to mention Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass and Iain M. Banks’s The Player of Games. Which I’ve managed to do anyway, you’ll notice. And why not? It was fun. The ludic impulse is one we learn about by following it — back through time, or forward, or along any of the branching possibilities and impossibilities fiction lets us explore.

Recent books recently read

The Freeze-Frame Revolution (Tachyon), the shortest and latest novel from Canadian Peter Watts, is as brilliant and enticingly acute as any of his earlier and longer work. Running with the common SF trope of a ship traveling the galaxy at sub-light speeds to set up gates enabling instantaneous transport, Watts bursts through accepted story outlines to tell us what life is like for those aboard. Cryogenic sleep shifts last hundreds of centuries. The mission, after millions and millions and millions of years, goes on under the implacable and inescapable eye of an artificial intelligence tasked with keeping the crew’s nose to an eternal grindstone. How can its favorite human Sunday Ahzmundin and a few thousand others possibly manage to rebel against their superhuman supervisor? With skin-creeping tension, sharply realistic detail, and action moving fast as thought, Watts shows us.

Armistice (Tor) is Lara Elena Donnelly’s second novel, the sequel to her award-nominated debut Amberlough. Though it’s evident there will be at least a third book in this series set in a 1930s-ish, Cabaret-like fantasy milieu, Armistice suffers none of the weaknesses usually inherent in literature’s middle kids. Instead of a conglomeration of thin, unsatisfying scenes meant to serve as a bridge between the overarching tale’s explosive beginning and its no doubt spectacular end, Donnelly gives us a gorgeous book about bridges — metaphorical ones: distasteful but pragmatic political alliances, undying loves, all the connections humans make as we find our way through the world. A few favorite characters from Amberlough reappear, such as Aristide, the flamboyant nightclub emcee and drug-runner now unwillingly enmeshed in illicit gun dealing; and Cordelia, guttersnipe stripper-turned-terrorist. Conspicuous by his absence is Cyril, a sometime spy for the Nazi-esque Ospies and Aristide’s presumed-dead darling, but Cyril’s sister Lillian ably steps up to fill his role. Her close physical resemblance to her brother shocks and disturbs Aristide; her similarly double-dealing relationship with her Ospie employers hinges on the son they hold hostage. Various rumors, rescues, and releases coincide toward the book’s end — always believably, always unpredictably, and always in a superbly written, Art Deco-inspired atmosphere of louche extravagance.

What if a proponent of mainstream literature decided to write a horror novel? Julia Fine’s What Should Be Wild (Harper) seems to approach that genre in the same spirit in which Margaret Atwood took on dystopian science fiction when she wrote The Handmaid’s Tale: rigorously conscious analysis of its underlying psychology combined with willful ignorance of her story’s literary forebears and the efforts of contemporaries along identical lines. Linking female sexuality to the concept of untamed woods and tracing its unfair hampering back to a 6th century patriarchalist invasion of Britain, Fine switches between the narrative of a “good girl” struggling not to abuse her literal power of bestowing life and death, and vignettes focusing on her ancestresses the woods has claimed as its own. The novel’s imagery is visceral, but the feckless protagonist’s passivity leeches it of strength.

Couple of upcoming cons

For years, con going cognoscenti have been informing me I really ought to head to Boston to attend Readercon. Welp, this year I’ll be there for sure, because I’m one of two living Guests of Honor. The other is the redoubtable Ken Liu, and the dead (or more politely, memorial) GOH is my idol E. Nesbit. Besides us official big deals, unofficial ones such as Samuel R. Delany and Ellen Datlow will be on hand to celebrate the genre’s literary aspects. Which is what Readercon is about, in case the name didn’t clue you in: books, magazines, and texts of all sorts — the power of narrativity.

Closer to home, Portland’s steampunky GEAR Con also has a specialized focus — but based on content rather than format. 2018’s theme is “the Great War.” World War I took place in the interstices between the Victorian era commonly associated with the steampunk subgenre and the later, Art Deco-influenced period referenced by Amberlough, Armistice, and that whole dieselpunk movement. SoGEAR Con’s usual “adorable chaos” (as one frequent attendee describes the Tesla-coil demos, mad tea parties, and other activities) may have a more militaristic bent this year. Streamlined bumptiousness, anyone?

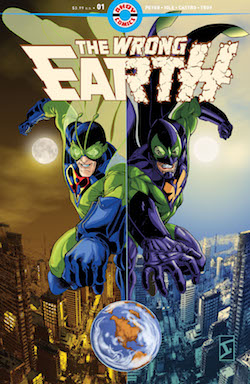

In which I say AHOY to comics writing

This morning, the Hollywood Reporter broke the news that former Seattle resident Tom Peyer is the editor-in-chief of a new comic book publisher called AHOY Comics. Peyer is a gifted comics writer who edited for Vertigo Comics in the line's heyday — he edited Grant Morrison's brilliant Doom Patrol run and was the assistant editor on Neil Gaiman's Sandman series. With publisher Hart Seely's guidance, the Syracuse-based AHOY will begin publishing comics this September.

I'm writing about this news because I have a personal connection to the company that I'm excited to share with Seattle Review of Books readers. Specifically, I'm writing comics for AHOY, and starting this September, in the first issue of The Wrong Earth, my work will be appearing in their comics. That issue will be a huge deal, featuring a killer lead story from Peyer, Jamal Igle, and a text piece from Grant Morrison.

Ever since I was a kid learning how to read with Charlie Brown collections and Superman comics, I always wanted to make comics. Once I realized that I had about as much artistic talent as a Roomba, I turned my attention to comics writing. I spent much of my early 20s publishing minicomics with friends — don't read them, please, they're horrible — and then the comics opportunities faded to the background as my attention became focused on journalism and criticism. The opportunity to write for AHOY, happily, has rekindled that old enthusiasm.

Working with Tom and Hart and Stuart Moore and the rest of the AHOY team has been a blast, and I'd forgotten how much fun it is to see an artist's interpretation of my script. I'm working with some fantastic cartoonists, and I can't wait for you to see their work. I've got a lot of backup stories in that first wave of AHOY Comics, and some special projects lined up in the months ahead.

Some housekeeping for what this means for the site you're reading right now: I intend to uphold the same high conflict-of-interest standards that we've always maintained here at the Seattle Review of Books. If there's a conflict of interest with AHOY Comics in any news story on this site, we will report it clearly and quickly in the article.

Obviously, I will not review any books published by AHOY Comics, or books from any publisher who pays for my work. I also won't review books by people I've collaborated with on comics work. I don't believe in impartiality — I've never claimed to write objective book reviews — but taking a paycheck from a publisher, and collaborating creatively with an artist, automatically puts a thumb on the scale. It's easier and simpler for myself and for my readers to recuse myself from any reviews with that kind of connection.

I will be tweeting about my comics work on my personal Twitter feed, but I will avoid deluging the site with announcements about my projects. Please reach out to us if you have any issues with SRoB's coverage of my comics.

And this comics writing gig won't affect my publishing schedule here on the Seattle Review of Books (or in my day job at Civic Ventures.) I can state this with confidence because I've been writing for AHOY for the better part of a year now, and it hasn't affected my workload elsewhere. You'll still see me here and on my day-job site on the same regular schedule that I've always upheld.

In any case, I'm excited to finally share this news with the world, and I can't wait for you to read my comics. Working with AHOY has been one of the most fun and rewarding experiences of my professional life, and I hope to keep working with them for as long as they'll have me.

I think the experience of writing comics has changed and will continue to change my approach to criticism on this site, and I'm excited to explore those different ways of looking at and responding to art with you. Thanks, as always, for reading the Seattle Review of Books and for joining us in our ongoing conversation with the literary arts.

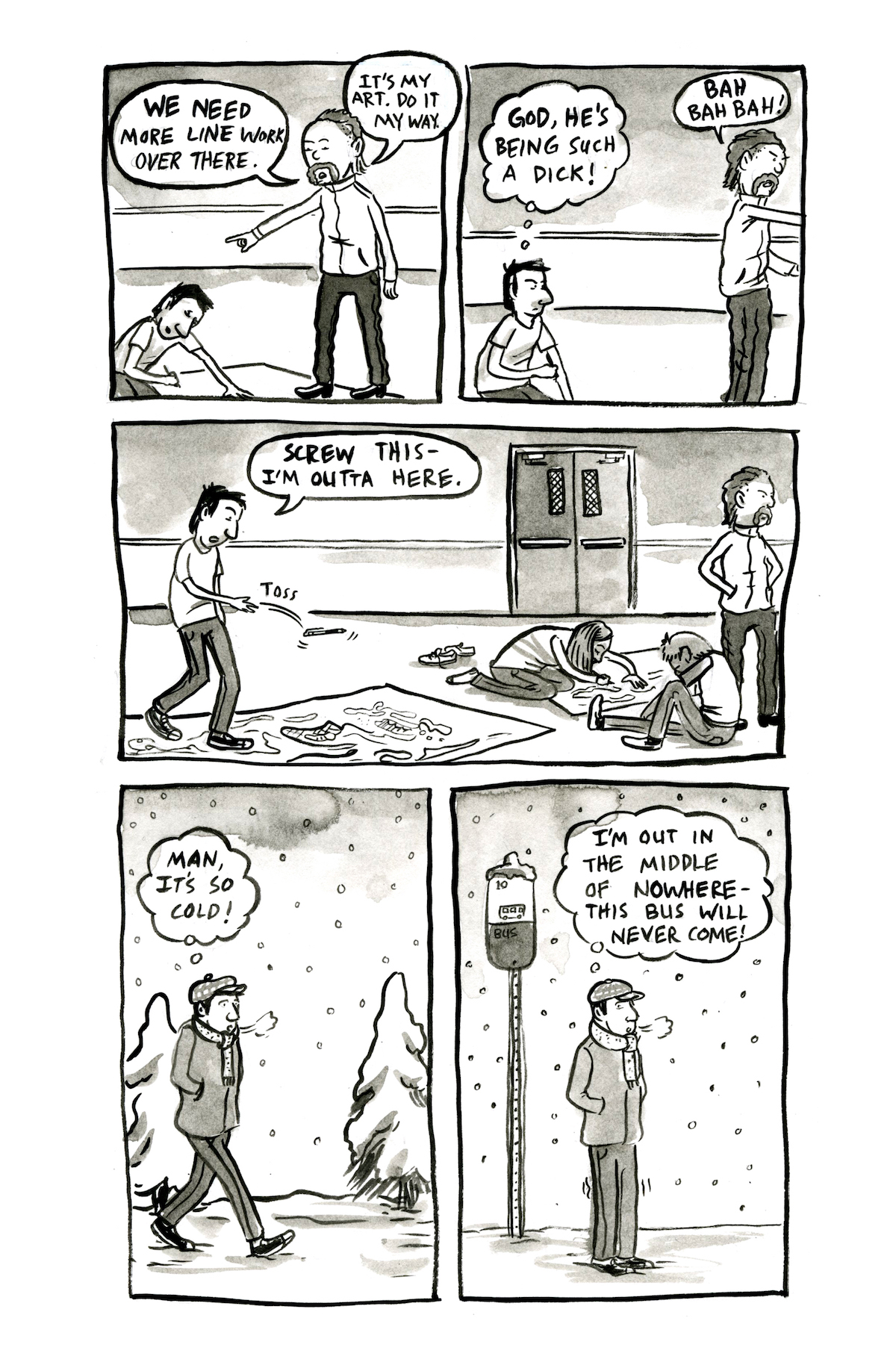

Thursday Comics Hangover: More than Crumbs

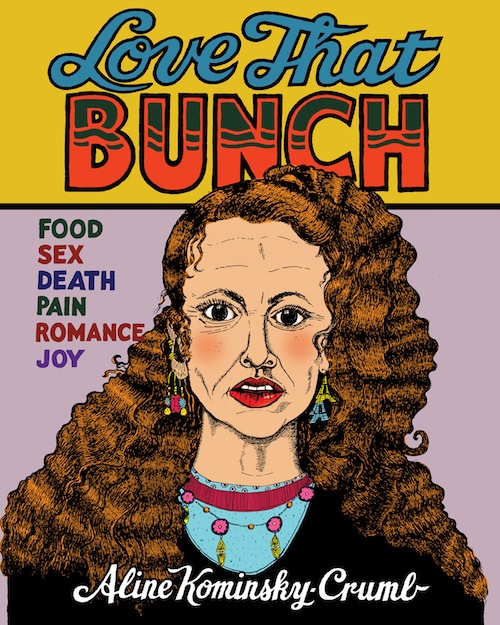

I'll admit, I'm not a huge fan of the jam comics made by the husband-and-wife team of Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Robert Crumb. The ironic cutesiness of those comics is nearly indiscernible from real cutesiness, and the juxtaposition of Crumb's formalist rigor next to Kominsky-Crumb's primitive illustrations is only good for a momentary thrill, and not a continued investigation. For a few years, Drawn Together, the collection of the married couple's collaborations, has been the only work of Kominsky-Crumb's in print.

Thankfully a new reissue of Kominsky-Crumb's solo comics, Love That Bunch, reminds us that she's a cartoonist in her own right, and not simply an extension of her husband's drawing hand. Bunch collects her early work from the 1970s and 80s, and it also includes a long new story, "My Very Own Dream House," that looks back on Kominsky-Crumb's childhood.

The act of simply flipping through Bunch can teach you a lot about Kominsky-Crumb's evolution as an artist. Her early work looks more like traditional comics, with smaller word balloons and more room for the art. But as you scan through the chronological progression, you can see words start to spread throughout the comic, like a mold outbreak on clean white tile. Eventually, Kominsky-Crumb's narration dominates every page, with up to six individual word balloons per panel. The drawings become smaller and smaller, focusing more on figures than backgrounds or settings.

But when you flip to "Dream House" at the end of the book, you can see Kominsky-Crumb's cartoons have come full circle: once again, she's allowing more room for her art to breathe, and she's not bombarding the reader with too much over-explanation. (One of my favorite panels is of Kominsky-Crumb's daughter, Sophia, vomiting while shouting "I HATE YOU, FRANCE!")

Kominsky-Crumb made her name with a kind of brutish honesty that at the time felt revolutionary. Not a lot of women were openly and frankly discussing sex and periods and body image issues when Kominsky-Crumb started out. And the fact that she illustrated these taboo stories with crude illustrations that didn't look traditionally beautiful only angered the establishment even more.

In retrospect, though, those early diary comics aren't really shocking at all. Looking back over four decades at the strips that originally had a kind of punk rock allure, they instead feel a little bit quaint. That's progress for you.

Instead, the strength of Love That Bunch lies not in striking moments but rather in the accrual of many such moments. It's a compelling and comprehensive account of what it was like to be a young woman at a very particular time, and it comes with its own meta-commentary about how Kominsky-Crumb feels about the work after nearly a half-century has passed.

If you asked me when I first read Kominsky-Crumb's comics in the 1980s whether I'd still be thinking about her work in 2018, I would've laughed at you. But these stories have aged well as a very personal document of a very strange moment in American history, while Robert Crumb's work has lost some relevance in my estimation. Who knows? Maybe in fifty years, young people will declare Kominsky-Crumb to be the real comics visionary in the relationship.

Book News Roundup: LeVar Burton reads Nisi Shawl

- Do you want to hear LeVar Burton read a short story by Seattle author (and SRoB contributor) Nisi Shawl in front of a live Seattle audience? Of course you do! You can find it on Burton's podcast feed, or you can listen through this embed:

If you are a woman and a poet, you should apply for this Poets on the Coast scholarship between now and July 6th. But please do note that you're on your own for accommodations, even if you win.

The good news is, you can buy a Carnegie Library for (relatively) cheap. The bad news is, it's in Seekonk, Massachusetts.

Can you guess what American teens are writing about these days? I'll give you one hint: it's depressing.

...on [Wattpad,] a site usually dedicated to painting innocent fantasies about being Harry Styles’s girlfriend, teens and preteens are living through a culture so dominated by guns that fears of their schools going on lockdown and fantasies of martyring themselves to save their friends have seeped into the stories they tell.

Honestly angry

Published June 13, 2018, at 11:56am

Roxane Gay reads at University Temple United Methodist Church next Thursday, June 21st. Her newest book is actually a reissue of her debut collection of short stories. It's maybe the most powerful book she's ever written.

Talking with Ellen Forney about Rock Steady, stability, and what's next

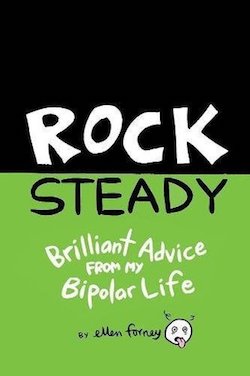

If I were in charge, Ellen Forney would be Seattle's Cartoonist Laureate — her writing and art would be all over the city's signs and materials, and would represent the city to the rest of the world. Just as Seattle is so beautiful that it's hard to remember sometimes how complex and difficult it can be to live here, there's something so inviting and approachable to Forney's art that it's almost impossible for a casual reader to recognize how much actual work goes into every illustration or page of comics that she does.

Forney's first full-length narrative, Marbles, was an account of what it meant to come of age as a bipolar cartoonist. Her new book, Rock Steady, is a how-to guide that serves as a companion piece to her memoir. Forney explains how she found stability and an acceptable level of normalcy as an artist, and she provides strategies for audiences to cope with their own bipolar traits or other mental disorders. We talked last week, the day after Forney returned from a reading tour for Rock Steady.

Okay, so you read my review. Do you want to talk about that? I know I spent a lot of time talking about how a lot of Rock Steady wasn't actually comics.

I knew right off the bat it was going to be difficult to shelve. The language of words and pictures is really broad, you know? And I generally think of comics as a narrative medium, and there are a lot of markers that we're accustomed to — panels and the other symbols, like word balloons.

Yeah.

But primarily the concern is they're narratives. That is my definition of "comics." I certainly wouldn't consider Rock Steady a graphic novel. There are some comics within it, but I would not argue that most of it would go into the realm of comics.

When I work, I like to take a look at all of the subject matter, all the information that I have to reference, and let that dictate the form in order to communicate it best. If I were to try to put [Rock Steady] into panels and make it more of a story — sculpt it as a story — the information would have gotten kind of diluted.

I would say that it definitely landed on the word end, in that spectrum of words and pictures.

When [Forney's partner] Jake and I travel, we keep a travel journal. And it's a lot like that. It's a lot of blocks of text. There are some full pages of text, with maybe an illustration or two. It's handwritten, which is an important part of it to me.

Okay.

When we're talking about big blocks of text, it's handwritten, so that communicates information differently from just a text.

I felt like I needed to use this range in order to tell these different things. The specificity of language is important to me. There are some things that really work better in words, that wind up being cumbersome if you try to do them in pictures or in words and pictures.

For example, any cartoonist that has tried to do a comic of a recipe has run into this, because it's very specific information, and to have that information sprinkled around in a comic makes it cumbersome to use. It's difficult to use as a reader, if you really want to cook from it.

And I reminded myself a lot as I was doing Rock Steady that communicating the information was my priority — that I didn't need to make it pretty if it wasn't coming out pretty.

One long stretch of text is in the chapter about substances, in dealing with partaking. I really wanted to communicate to people who were wrestling with issues around substances.

This was something that I talked about in Marbles, — about dealing with smoking pot, and my whole identity around being a pot smoker. I didn't want to depict anything too specific. I generally say that words are explicit, and pictures give more of an abstract feel, or a mood. Obviously that's a big generalization, because you can do a whole story in just pictures.

But in something like substances, there were ways that I could be more general just using words — where if I was actually depicting someone smoking pot, then somebody who was having an issue with alcohol might not really relate to that. And I didn't want to make it funny. I really wanted to be really careful.

It's also a really controversial take on substances. I don't mean to dwell on the substances part too much, but I took a lot of time and revisions and editing, and I worked with addiction psychiatrists on that part.

Having that be in mostly text allowed me to be really explicit, and it also allowed me to sidestep drawing someone using or partaking. That's an example of a place that I decided that I was going to let it be wordy, that the information would dictate the form. And even though that was about as far from comics as I would get, I had to be okay with that, and trust that enough readers would be able to hang with that.

Anyway. So that was my lengthy response to a concern that you brought up, that was something that I had thought about. Which is, it's not a comic. It's not a narrative from beginning to end like Marbles. But the kind of information that I wanted to communicate, and the amount of information that I wanted to communicate, wasn't going to fit into a narrative structure. I wasn't going to be able to fold all of that into a longer narrative.

And Marbles Part Two doesn't have much of a story arc. You know, I stayed stable.

And that's not much of a plot, yeah. I felt bad that I spent so much time on whether or not Rock Steady was a comic in my review, but I do think that was something that I thought that readers would want to know, right? But at the same time, I was concerned I was doing some sort of bro-y, gatekeeping sort of thing? Because I'm not that interested in whether it's comics or whether it's not comics. It's more like, does it work?

I think that those points are really important. I would say that probably a good block of people who are gonna pick up Rock Steady are familiar with Marbles and not the rest of my work. It has a lot of the trappings of a comic, and it doesn't read like a comic. I knew that Rock Steady would run into that — if you see it on the table in bookstore, what it is isn't necessarily clear right away.

And I know that that's a thing. I remember an art teacher talking about your expectations, like if you have a glass of brown liquid in front of you and you think it's apple juice, and you sip it and it's actually bourbon, you're gonna spit it out. And so that I know there are a lot of readers that are gonna have to kind of readjust, like, 'Oh, it's not a narrative. Oh, it's not Marbles Part 2.' It's a companion book. It's a how-to book. It's a manual that uses the language of words and pictures in a number of different ways, I guess.

But there's graphic elements that go into even the pages that are all text, right? I mean, that's not your handwriting, right? That's not how you write a shopping list.

Right.

The writing on the page is not just you dashing something off. You're actually thinking about how the words go on the page, right?

Right.

And there's design to that as well. And that's something that I don't think I got across in my review. There's still cartooning even if there's not a drawing on the page. You are still cartooning, right?

Well, because there are so many different skills and techniques that go into doing a page. And I rarely use panels, I rarely use a grid. So really, every page is sculpted from what the information is.

And ideally, it reads easy enough. That's the idea. That's my aim — that it reads easily enough that you think, 'Of course it's that way. Of course that's how it's written. Of course that's how it's laid out.' My work is meant to come across as really spontaneous — its kind of friendly, welcoming quality, is because of a certain sense of ease.

Yeah. There's a sense of ease and there's always a sense of approachability.

But it is very designed. It is very designed, and redesigned, and tweaked, for sure. And it gets hidden. Every now and then somebody will say something about how effortless [my work] is, rather than how effortless it seems. I'll just go ahead and take that as a compliment.

It's interesting you were talking about the substances, because I don't know if you could draw somebody doing drugs in the way that wouldn't feel, on some level, inviting. Because your art is very approachable, and even if you draw something that's supposed to be bad, there's a level of fun and appeal that comes across to the reader. So, you definitely have a level of responsibility there.

Yeah. It was a really tricky one. I didn't want to draw something that was cute. I drew a little tiny bit of cute in the very beginning so that it kind of eased your way in, with two beer bottle characters.

In this book, you talk about the importance of stability. And that is something that a lot of people who I have interviewed would say is not important or is antithetical to art. Some people — and I'm not in this category, but a lot of people are — think that art has to be spontaneous and uncontained and unstable. And so I was wondering if you've gotten any pushback on your call for stability in art.

I would say that, at least from the people who I hear from, there is a lot more relief that it's possible to be creative and be stable. It's a great, big fear that stability is gonna mean losing a certain spontaneity or passion or creativity. And my saying that it's possible to be stable just kind of gives a flicker of hope. I'd say that that's the primary reaction that I've gotten.

And one way to think about that that doesn't feel restrictive is keeping a regular rhythm. Think of Led Zeppelin. If you have a really solid rhythm section, then you can have guitar solos, you can go out into creativity and innovation, and it's still grounded and you're going to come back to this rhythm that keeps everything together.

And so if you think about your daily rhythm that way, then you can go off and do all sorts of things. I mean, an example would be like, "I want to go to the mountaintop for that crazy artist week-long residency." Great. Make sure you get enough sleep. Make sure you're eating. You know, take care of certain things in your routine and you can do your guitar solos.

Speaking of changing rhythms, you've been on a book tour. I usually talk to people before they go on tour, so this is a nice change of pace. What was the tour like?

It was great. It was really fun.

What was the response to the book like on the tour?

I mean, I am back as of yesterday. I have a little processing to do.

People seem to be getting the point — that this book is coming from a point of view of someone who's had this experience and has an investment in these practices and ways of thinking. Most of the books [in this genre] are by therapists or doctors, and this information is really different, coming from me.

Also, I've gotten people really relating to things that are really important to me, that were really important to me to include, like messing up. It's okay to mess up, most of the time — it'll be okay or it'll be fixable.

It was really embarrassing when I put in the book how I accidentally took Vitamin D instead of my mood stabilizer, Lamictal, for three days. That's a bad mistake, and for me, it was overwhelmingly embarrassing. But I dealt with it. I looked up information on the internet, realized that actually I was kind of in danger territory, called my doctor, figured out what we needed to do, and learned my lesson, and went on. I don't make that mistake anymore.

That's a big part of taking care of ourselves: You're gonna mess up. What are you gonna do then? I think it seems so far like people are kind of getting that.

You might not want to hear this question so close to publishing a book, but I'm sure that my readers would like to know. What are you working on next?

Right.

Sorry.

No, that's okay. The thing that I'm toying with now is a book that covers a lot of the same aim as Rock Steady, except for teens. When I was first starting to do Marbles, a friend of mine, who is a high-school English teacher, said, "please make this available for teens, because they just need it so much."

It's such a huge issue in schools: in your teens is really when a lot of the symptoms start developing and coming out, and diagnoses are kind of starting to come into play, and a lot of kids are getting on medications. It's a really confusing time, and there are a lot of issues in the air that aren't clear.

With Marbles, I had to tell the story how I had to tell the story. It turns out there was too much drugs and sex for it to get into high school. Not that plenty of teens didn't read it, and I've heard from plenty of teens, but it couldn't be officially taught. Well, I mean, it has — I talked to a high-school class — but rarely.

Yeah, you had to Judy Blume it.

Yeah. When I was starting Rock Steady, that was one of my aims, that it be available to teens. And I had a three-hour talk on the phone with a high-school psychologist/counselor, and I wound up realizing that I wasn't gonna be able to do that. There are some issues that are just way too different. Most high-schoolers are still on their parents' insurance, so dealing with finding their own health issues is different. Agency, just in general is a big issue. They just don't have the kinds of freedoms that adults who are taking care of themselves do.

I have mixed feelings about medication in general, and I hope that that is very clear in Rock Steady, that I don't preach meds. I don't think that they are necessary for everybody. I don't think that they're necessary for the long-term for everybody. I think that there's a lot of over-diagnosing and over-medicating now. And teens, so many of them are on meds now. Their frontal lobes are still developing, and it feels like a really even more complicated piece of an already complicated issue that I would wanna deal with differently.

And there are a lot of other issues that are different, like questioning the diagnosis. It's really different for a teen to be like, 'Mom, Dad, Doctor, I'm not sure about this diagnosis that you've given me.' It's a big deal, and to have that in a book, it'll be really tricky.

I decided, "Okay, this isn't something that I'm gonna be able to do with Rock Steady. That's a separate project," and so that's what I'm thinking about now. That's the long answer.

I'm just trying to wrap my head around how I'm going to do that, which groups of teens I'll turn to, if it should have fictional elements. Should there be more narrative elements? I don't know. I feel like I am now kind of opening it up, more, to different possibilities. 'Cause it's gonna be tricky.

In case you're not bummed enough by the news, Portland's feminist bookshop In Other Words will be closing at the end of this month. You likely know the shop from its appearances in Portlandia, though the staff entirely disavowed the television show in 2016. Kristi Turnquist at the Oregonian writes that the store is closing for...

...reasons including increased expenses and the lack of funds, volunteers, and board members, along with an inability to "reform and re-envision" a space founded on "white, cis feminism (read: white supremacy)" to make it more reflective of contemporary feminism.