Portrait Gallery: Yaa Gyasi

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

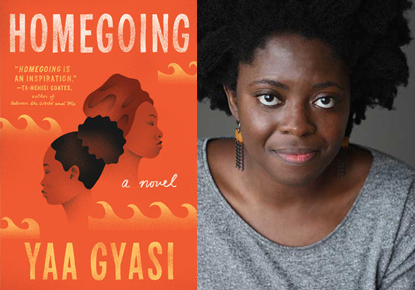

Seattle Reads Homegoing, by Yaa Gyasi

This year's Seattle Reads choice is Homegoing, the debut novel by Yaa Gyasi. (You can see a calendar of Gyasi's appearances on SPL's website.) Homegoing tracks the lives of two sisters born in the 18th century. One is captured and sold into slavery, the other marries into a privileged family. Gyasi follows the sisters and their descendants through history with the confidence one normally associates with someone who has published a long line of novels. It is not a DFW-style doorstop, but it somehow spans 250 years from cover to cover.Gyasi is arriving in Seattle at a high point in her career - when Ta-Nehisi Coates refers to you as "an inspiration," you know you're doing something right - but it's easy to imagine that she'll ascend to even higher peaks in years to come. The Seattle Reads program is a great way for our city to stake a claim on Gyasi's future success, to ensure that she'll return to share her victories with us for years to come.

(Various locations and times, free.)

The Ruritanian gambit

Published May 17, 2018, at 12:00pm

What if ... the Prisoner of Zenda played out in today's Romancelandia? Happily ever after, says our romance columnist, Olivia Waite.

Thursday Comics Hangover: A Deadpool comic for people who hate Deadpool Comics

Last week I did something that I have never done before: I went into a comic book shop and I paid money for a pair of Deadpool comics. Even more embarrassing: I read them and I loved them.

Deadpool never really clicked for me. His breaking-the-fourth-wall schtick is rarely handled well and I like my superheroes to have moral codes. I don’t think the character represents an age of decadence in superhero comics or anything histrionic like that. I don’t begrudge Deadpool fans their hero. I just don’t think he’s funny or original. (And the Deadpool movie, whose sequel is in theaters tomorrow, seemed remarkably on-brand in that way: I didn’t think it was especially funny or smart, but it really clicked for certain audiences.)

But Marvel Comics is glutting comic shop shelves with Deadpool comics to cash in on the new movie, and one of the miniseries they’re publishing is titled You Are Deadpool. If you’re interested in playful experimentation in the comics medium, you’ll want to pick this one up — even if you’re not a Deadpool fan.

You Are Deadpool is a choose-your-own adventure comic. The way it works is this: every panel in the comic is numbered. Whenever Deadpool faces a dilemma, the reader can choose which way to go, and each decision sends them to a different panel. “If you’d like me to have a flashback,” Deadpool tells the reader in the first issue, “go to 72. Alternatively, if you’d rather get right into it, go to 66.” It’s not all fight-oriented; later in the series, readers get to choose whether Deadpool shares his emotions through painting (“go to 16”) or poetry (“go to 14.”)

There are more rules, too — “cool” violent actions increase Deadpool’s Badness Score, while crawling through tunnels adds to his Sadness Score. And readers can “play” combat in the book by rolling dice to determine the outcome of certain battles. But readers can also “cheat” and barrel through the book, flipping back and forth to see the outcomes of various actions.

The big difference between this Deadpool book and every other Deadpool comic is the writer, Al Ewing. Ewing has as close to a perfect record as any Marvel writer — he writes stories that reflect back on decades of Marvel history while also pushing forward into new concepts and, in this particular case, storytelling techniques.

But every comic is a collaboration, and Salva Espin’s artwork in issue 1 is a terrific complement to Ewing’s script: his art is clear and just cartoonish enough to sell the ludicrous premise. Paco Diaz’s art in issue two — in which Deadpool is zapped back in time to Marvel’s earliest days to riff on the Fantastic Four’s origin — is a little stiff for my tastes, although Diaz does do a pretty good riff on early Marvel art.

I’m a sucker for this kind of formal play, and I have to begrudgingly admit that Deadpool is exactly the right character for this kind of a story: his ability to address the reader directly helps guide novices through the book, and his unpredictable amoral tendencies make him a believable audience surrogate for every course of action.

You Are Deadpool hasn’t converted me to a hardcore Deadpool fan, but it has opened up my understanding of what the character is capable of doing in a story. Ewing’s excitement for the possibilities of the medium prove that old adage about how in the right hands there’s no such thing as a bad character. You Are Deadpool proves that Ewing’s hands are abler than just about anyone in mainstream superhero comics.

Next Tuesday night at the Central Library downtown, Seattle City of Literature will be throwing a party to celebrate the fact that our city has been officially designated a UNESCO City of Literature. This is just a straightforward party — no readings, no lectures, no ribbon-cuttings. Just a bunch of Seattleites enjoying drinks and snacks, talking about the future of Seattle's literary scene as we connect with UNESCO's giant Creative Cities network. The party is free for everyone, though City of Literature requests that you RSVP so they know how much punch to put out. The party starts at 7 pm. Come have fun, and learn more about the plans to celebrate Seattle as a world-class lit city.

Book News Roundup: Ebooks run amuck

Are you familiar with The Humble Bundle, which sells online items — often games or pieces of software — for charity? The current Humble Bundle features up to $445 worth of sci-fi ebooks to celebrate the 2018 Nebula Awards. You can buy various tiers of books starting at a buck, but I'd urge you to splurge on the $20 or more bundle, which includes some great books including James Morrow's Only Begotten Daughter, which is one of my most-loved reading experiences of all time. And when we're talking about books that I love, this bundle also features Carol Emshwiller's The Mount, which is a favorite reading experience of mine.

How are ebooks really selling? According to Quartz's Thu-Thuong Ha, the answer is complicated, and it involves Amazon's shitty business practices.

Speaking of Amazon, it looks like they're shutting down Kindle Worlds, which was supposed to be an officially sanctioned fan-fiction outlet for intellectual property including Veronica Mars, GI Joe, and, weirdly, the works of Kurt Vonnegut.

Anyone know where I can find a copy of this book?

this is the only book on my wish list pic.twitter.com/bKH461FadS

— stephanie (@mckellogs) May 15, 2018

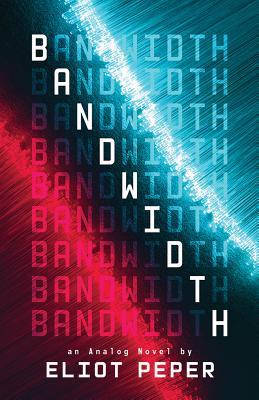

Eliot Peper wants to help you find the future

When he's not editing the forward-thinking science/fiction magazine Scout.ai, Eliot Peper writes sci-fi novels. His latest, Bandwidth, is a neo-noir centered around a lobbyist who is nearly crushed under the massive weight of information overload. Peper talked with us about gender roles in noir fiction, where he looks for sci-fi inspiration, and how we're still wrestling with the ramifications of the internet. This interview has been lightly edited.

You’ve written a noir novel and you’re obviously a forward-thinking guy, and I’m curious how you approach writing this noir-ish hyper-masculine genre in a modern context. I think that you do have an interesting angle on it, but if I were to tell a reader to try a noir novel starring a character named Dag Calhoun I think some people might balk. You know what I mean?

Sure. It’s interesting writing Dag, because he’s the first straight male character that I’ve written as a single protagonist. I have one other book, Cumulus, where there were three point-of-view protagonists, and there was one other male character in that book. But Bandwidth was actually the first, and sort of interestingly, Bandwidth is part of a trilogy, but it’s not a linear trilogy.

So the second and third book all take place in the same universe, have a lot of the same cast, but they different protagonists and they have different narrative and character arcs. You can actually read each of the books independently if you wanted to. And so, it was an interesting learning experience for me getting comfortable writing Dag, which is sort of ironic given that I am a straight, white, male.

I am every category that would fit that genre in theory, but that’s actually not what most of my writing has been like to date. So it was interesting coming at it from that angle. And I actually had fun with it. Unfortunately, there’s a great example that I can’t give because it would be a spoiler. But I really did try to play with some of that stuff in the book.

Yeah, there’s a scene very early on where Dag’s led around by his erection, and it felt like you were very cued into the traps of the genre.

Yeah, and I think as you read on, you might find some fun psychological ones as well. And so I found that to be an interesting experience: it was a learning opportunity for me to try to be more aware of the cultural context that the story would fit into, and then it was also interesting because it was my first time doing it, so that was fun.

I didn’t actually approach writing Dag much differently than I’ve written other characters in the past. The first trilogy I ever wrote — the first book came out back in 2014 — had an African-American female protagonist, and one of those things that I heard from readers in that community was that the story spoke to them in part because it just like how anyone would look at the world. It wasn’t actually that specific. Her cultural background was not actually relevant to the story and it wasn’t a big deal basically in the context of the story — even though for other characters there were impacts.

But it was not a book about race, and I think that for readers sometimes that can be a positive thing. It’s not intended to be a book about masculinity, even though that is woven through the story and certainly relevant to its cultural context. I don’t know if that answered your question.

No, it did. I think it’s an issue that people who read my site would consider when browsing the cover copy and considering picking up the book.

Yeah, that’s true. And one thing I would say that might be relevant to those readers is that not limited to Dag’s gender identity or cultural background or anything like that.

What I find most interesting as a novelist is ambiguity, shades of gray where there’s a lot of conflict. So whenever I’m working on any kind of character, I’m always looking for that zone where their hopes and fears intersect, and the weird patches where they’re not actually sure about their own moral standing or certainty — where they’re not just charging in with this very, very clear sense of what is right and wrong. I’m much, much more interested in the nuance in the middle.

And that applies to Dag’s identity and it applies to his worldview. He’s not someone who has a really clear sense of moral superiority, and he’s sort of a conflicted protagonist. He’s not a hero right off the bat. And it also applies to the worldbuilding.

It’s funny because sometimes I hear from readers when they read Bandwidth, they’ll call it a dystopian novel. And what I find really interesting about that is that I did not think of it as a dystopian novel while writing it. There are certainly some dark things that happen in the world — some of the impacts of accelerated climate change and stuff like that are certainly dark — but there are actually some really beautiful and wonderful things about this future that we might not have imagined either. And so,

I always try to look for those shades of gray and that nuance, so I hope that even if the description makes you think that it’s a very straight up masculine noir story, that if you actually give it a read and take the story for a spin you might discover that there’s more complexity there than you might have guessed otherwise.

You’ve got a concept in the book called the Feed. Most people receive their media, their information in the form of a feed, which is like a gutter with information flowing through it in more or less chronological order. Were you picturing this sort of gutter of a feed when you were thinking about The Feed in this book? Do you think that we are trapped in this informational flow for the near future, this particular way of getting information?

Yeah, so I guess the way I think about it is that digital technology, computers, and computer networks have so vastly decreased the cost of storing and distributing and sharing and publishing information that information is now free. We take it for granted. We take Wikipedia for granted, we take Google for granted, we take all of these things for granted. And what that means is that compared to any other human at any other point in history, we walk around with all knowledge in our pockets at our beck and call.

And that can be very empowering in very obvious ways: your sink is broken, so you look on YouTube for this precise model and it will show you how to take it apart and fix it. But it also presents us with this new challenge that no one has ever had to face before, and that is, when you have this surfeit of information, how do you actually find the useful, relevant stuff? And we are currently at the very, very beginning point in history of ever having to improvise through solutions to that problem.

And so, some obvious examples of solutions that we are currently experimenting with are Google search, where you ask the internet a question and they have an algorithm that takes, I think, between three and four hundred independent variables to automatically calculate what the results should be for you. It’s not just ranked links, it is incredibly sophisticated.

If you use Gmail or similar large services, those services are now becoming algorithmic. You’ll probably notice that in your email inbox that things get automatically filtered into different categories like “promotions” or “social.” The algorithm can be useful because it becomes this filter that allows us to ignore the stuff that’s less important, or to categorize information for us in some way or another. And I think that there’s really no way to get around the fact that when you have all of this of information you need to be able to filter it.

Just as most Netflix viewers have experienced, when you go to watch Netflix a lot of the time you end up spending 45 minutes trying to decide what to watch, and you end up never really watching anything, right?

Right.

And that points to how bad we are at this. For all the news items about the power of Big Data and social media, this is a massive information problem that we are really only starting to come to grips with. And I think that there are so many really complex issues baked into how you filter information that we’ve never had to deal with before.

I don’t know if you’ve read much about bias baked into machine learning models, but there’s a great example in policing where you have a bunch of arrest records that show certain types of people are arrested more often than others. It doesn’t take into account that it actually might be reflective of a much greater systemic corruption and not just the fact those should be the people getting arrested.

There are so many decisions baked into that, that many of us don’t even realize are happening. So we experience the results of the feed, the architecture of those feeds is opaque to us. And I think that is a really big challenge that will be one of the big issues of this century. Because the media you consume, the information you access, shapes the way you see the world and shapes the decisions you make — both in your own life on a very personal level, like, “what Netflix show am I gonna watch?” and also, at a community level, even up to the level of the federal government: “what kinds of rules should we have about how people do things on the Internet?”

Yeah, so this is a question I think that probably every sci fi author gets asked a lot, but it seems like you’re cutting very close to the modern time with this book so I’m going to ask anyway: how do you write about the future without getting steamrolled by it?

Well, I very well might. Hopefully, my answer to this question will have somewhat of a halflife. We’ll see.

I think that science fiction is really about the present, not about the future. So if you read 1984, it was written in 1948. And I think it was written about 1948, and I think that the reason why it feels relevant in 2018 tells us more about 2018 than about George Orwell. Or I guess it tells us that he is an amazing novelist and an amazing observer of the human condition. But I think it speaks far more to the feeling of living in a society that is beyond our control and the paranoia that can come through that. It’s a great metaphor for state surveillance.

What I find interesting about science fiction as a reader is that it sort of transports me into this plausible alternative reality. And because it is an alternative reality, it actually gives my imagination more space because I’m not constantly questioning the veracity of the every fact. And then when I return, hopefully, it’s a very compelling and transformative experience. And so when I come back to my present reality, my own world view has shifted a bit so it actually helped me challenge the assumptions that I make every day when I look at the world. That’s what I get out of science fiction as a reader.

As a writer, I have no way to predict the future. If we were able to predict the future, it would be very, very boring, and science fiction would actually be totally useless. I think that the power of science fiction is that it can paint multiple different futures, and that by experiencing those very different futures then we’ll have more context for the decisions we make today.

But I have kind of a game that readers might want to try in their own lives just for fun, and writers might find it useful if they’re trying to write about the future. Rather than trying to read a trend report, or something like that, try to look for weird details in the present rather than having a thought experiment about the future.

So as an example, William Gibson has that famous quote, “the future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.” And how can you find those pockets in the present day of future that has not yet been evenly distributed? So I’ll give you one example: Google’s chief economist, Hal Varian’s hot tip for predicting the future is to look at rich people, which initially sounds horribly Silicon Valley techno-libertarian, right?

Yeah.

But if you take it a step deeper, you can actually find that it’s a really useful. Who were the people that could afford to drive cars? Rich people. TWho are the first people to ride on trains? Rich people, because they were the only people who could afford them. If you look at the history of technology, rich people are almost always the earliest adopters because the new technology that has been developed is only accessible at that pricepoint early on, before it becomes mainstream.

So if you want to think about what might the world look like in 10 years, or in 20 years, one fun way to think about that is: what are things that only very rich people do today, and what if those things were things that everyone had access to all the time?

So that’s one fun way to do it. I would take that a level deeper and say, don’t just limit it to rich people. One of the communities that I like to learn from is hobbyists — people who do things for the intrinsic joy of doing the thing. They’re doing stuff just for fun, not for financial gain, not for fame or fortune. They’re doing it because they just get a lot of joy out of tinkering and screwing around with whatever their hobby is.

Often those communities also can turn out to be pockets of the future that has arrived early, because they’re so absorbed in whatever it is that they’re passionate about that they make these strides that nobody even realizes could be really transformative for our society as a whole until they’re much more widely distributed. A good example of that would actually be very, very, very early Silicon Valley, where you had a lot of people who were playing with computers. This is decades and decades and decades ago, basically for fun, right?

Yeah.

They would screw around and trade stuff with friends and trade ideas with friends. The way of thinking they developed has now come to be a huge part of the economy and of our of politics and of the things we use everyday. And so, if you are a science fiction writer and you want to try to tease out what might be an interesting scenario, try those two. Think about what rich people might be doing and what if everybody had access to it, and then think about what hobbyists might be doing and what if everybody was doing that all the time too.

That’s great. Both of those tests sort of apply to Apple, because Steve Jobs started out as a phone phreak, but then obviously the luxury computing component came into it later on in his career.

Yeah, absolutely. The third thing, I guess the closer, I would say, is that I read very widely. But the one genre that helps me think about the future most effectively is reading a lot of history. If anybody is interested in trying to think more flexibly about the future, I think that history is the best guide.

Just as with reading good science fiction, reading good history shows you in how many ways the world can change. The lives we live today are so fundamentally different than the lives of ancient Romans. In fact, my grandparents wouldn’t even understand what I call a job today. And they certainly wouldn’t understand the stuff that I use every day and how I’m able to communicate with people. We live in a world full of wonders and we’re so jaded because we use it all the time that it’s really easy to take everything for granted.

But if you read history and you really try to imagine yourself living in that era, you’ll very quickly think about how malleable our world is. Not just the technologies we use, but our cultural institutions, our political instructions, our daily life. It has changed a lot, and I find that thinking in those ways tends to relax the constraints that I have on my own thinking when I try to look forward.

Over at Fantagraphics' online comics magazine The Comics Journal, Seattle cartoonist Colleen Frakes is publishing her diary comics about a visit to a robot-and-comics convention in Alaska. The first strip begins, "I had been feeling angry for a long time. My job was bad, the president is bad, the news is bad." If you can relate, you'll likely find a lot to enjoy here. It's a special treat to see Frakes working with color: those early panels of her colored in with a sloppy red shroud to depict her anger indicate what she can do when she's not constrained by the limitations of print. Day two went up this morning. Go check out the strips, and then we can all start pestering Fantagraphics to publish a long-overdue collection of Frakes's minicomics work.

Able, abled, abler

Published May 15, 2018, at 12:00pm

Nicola Griffith's new book So Lucky is a great story, a snappy read, and a manifesto about living with multiple sclerosis.

The Scare Crow

One must have a mind of a gardener

To regard the dirt with thoughts

Approximate to wonder, to live inFascination of the earthworm —

Pink hermaphrodite of the jiggling zither;

And to behold the Mrs. Jekyll rose,To note the light’s addictive sugaring

In sun gold tomatoes

And not to think of quietPromises in the winter’s chill and frost,

The past delicious juices, that in time

Attaches bitterness to skin, to rot, then snow —Which alters the birds predictive packages of shit —

Companion to the gardener who knows

She must garden through the rain and in light snow.

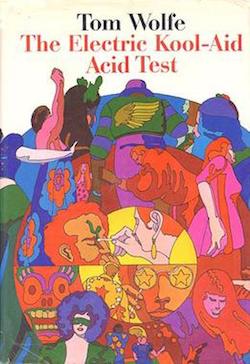

The New York Times is reporting that journalist and novelist Tom Wolfe passed away in Manhattan yesterday. He was 88 years old. Wolfe's stylish brand of New Journalism has been an unmistakable influence on generations of young reporters from the 1960s to today. I read pretty much all of Wolfe's nonfiction work growing up, and his rhythms and cadence runs so deep into me that I still unconsciously copy his tics all the time in my work. One of my favorite Wolfe passages is the rant about hemmorrhoids that opens his essay about the "Me" Decade for New York Magazine.

Maybe you haven't read Tom Wolfe, and maybe the tributes on the internet are convincing you that you should give him a try. Let me recommend a course of action: The latter half of Wolfe's career was spent on a series of gigantic satirical novels — The Bonfire of the Vanities, A Man in Full, I Am Charlotte Simmons — that were received to diminishing critical returns. If you're curious about Wolfe's work, I'd send you to his non-fiction titles first — The Painted Word, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, The Right Stuff — and then encourage you to try the novels (in chronological order from oldest to newest) if you really like what you find. Be advised that not all of his work has aged well, but that's true of pretty much all journalism. He was intensely of his time, and because he was intensely of his time, he is a writer who will shape the face of writing for decades yet to come.

Get tickets now for Seattle Arts & Lectures 2018/19 season

Every year Seattle Arts & Lectures puts together one of the best event calendars in town, and their 2018-2019 season is no exception. Tickets are already available for the signature Literary Arts series, featuring an all-woman lineup this year, and a brand-new series focusing on journalism and the importance of a free press; tickets for other series — Women You Need to Know (you do!) and the iconic Poetry Series — go on sale over the next week. Check out our sponsorship page for specific names and dates.

Sponsors like Seattle Arts & Lectures make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? Get your stories, novel, or event in front of our passionate audience of readers. Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from May 14th - 20th

Monday, May 14: An Evening of Mahmoud Darwish Poetry

Prominent members of Seattle's Palestinian community, including poet Lena Khalaf Tuffaha and architect Rania Qawasma, celebrate the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish in a bilingual reading. Local poets Elizabeth Austen, Rick Barot, Jourdan Keith, Claudia Castro Luna, JM Miller, and Susan Rich, will also read work. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, May 15: So Lucky Reading

Nicola Griffith is one of Seattle's leading writers, by which I mean where Griffith leads, others follow. Tonight, she launches her latest book, a novel titled So Lucky. It's about a recently widowed woman who discovers that she has multiple sclerosis. You'll be hearing a lot more about this book here over the course of the week. (Griffith is also reading at Elliott Bay Book Company on Wednesday night.) Phinney Books, 7405 Greenwood Ave. N, 297-2665, http://phinneybooks.com, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, May 16: WordsWest

The West Seattle literary series, which recently helped to save independent coffee shop C&P Coffee Company from closing down, continues with the theme "Home Unsettled Home." The headline readers are Rachel Kessler and Matthew Zapruder, so this is going to be a lot of fun. C & P Coffee Co., 5612 California Ave SW, 7 pm, http://WordsWestLiterary.com/, free.Thursday, May 17: Seattle Reads Homegoing

See our Literary Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.Friday, May 18: Jack Straw Writers Program

Every year, Jack Straw recruits a squad of emerging Seattle writers and teaches them how to be more confident when reading, recording, and producing their work in other media. These readings are a great way to see what the writers have learned. Tonight's readers include Jalayna Carter, Sarah María Medina, Daniel Atkinson, and Rachel Trignano. Jack Straw Gallery, 4261 Roosevelt Way N.E., 634-0919, http://jackstraw.org, 7 pm, $5.Saturday, May 19: Seattle's Book Fair

Presented by Seattle's Reading Divas, this celebration of local authors including Tela Allen, Alecia Coody, Leslie Cronkhite, Latoya Ralliford, Royal Prince, and many more features food, signings, games, music and a bunch of books you can buy. New Holly Hall, 7054 32nd Ave S, 12pm - 6 pm, free.

Sunday, May 20: Against Memoir Reading

Michelle Tea is a goddamned titan. Her latest non-fiction book, an essay collection titled Against Memoir, is subtitled Complaints, Confessions & Criticisms, and it covers topics as wide-ranging as lesbian biker gangs and ice cream shops. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Seattle Reads Homegoing

This is the 20th year of the Seattle Reads program, which was originally (and, in my opinion, more successfully) known as "If All Seattle Read the Same Book." You know the idea by now: the Seattle Public Library chooses a book and delivers many dozens of copies to branches around the city. Then, in May, they bring the author to town to read in multiple locations and formats over the course of about a week.

This year's Seattle Reads choice is Homegoing, the debut novel by Yaa Gyasi. (You can see a calendar of Gyasi's appearances on SPL's website.) Homegoing tracks the lives of two sisters born in the 18th century. One is captured and sold into slavery, the other marries into a privileged family. Gyasi follows the sisters and their descendants through history with the confidence one normally associates with someone who has published a long line of novels. It is not a DFW-style doorstop, but it somehow spans 250 years from cover to cover.

Gyasi is arriving in Seattle at a high point in her career - when Ta-Nehisi Coates refers to you as "an inspiration," you know you're doing something right - but it's easy to imagine that she'll ascend to even higher peaks in years to come. The Seattle Reads program is a great way for our city to stake a claim on Gyasi's future success, to ensure that she'll return to share her victories with us for years to come.

(Various locations and times, free.)

The Sunday Post for May 13, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

(MORE) guided journalists during the 1970s media crisis of confidence

(MORE): A Journalism Review ran from 1971 to 1978, tweaking the nose and stepping on the toes of mainstream journalism, running stories the big names spiked and saying why. Sometimes the tweaks were juvenile, like compiling a raft of “bus plunge” stories from the New York Times. But often (MORE) brought real news to light and at the same time reminded mainstream media that their peers were watching. Kevin Lerner’s history of the publication is packed with great stories and thoughtful reflection about the role of the journalism review in today’s embattled media landscape.

In ways that echo the 1970s, American journalism is facing a crisis of confidence once again, and the most self-aware journalists are beginning to critique themselves as much as their audiences are. The current model of journalism is again struggling to adequately describe the world it is trying to cover. The best minds in journalism can find each other easily now, but another (MORE) needs to finish the job it started — to make the press more self-aware, more self-critical, more flexible, and better able to rethink its best practices in the face of its own failure.

We Need More Non-Binary Characters Who Aren’t Aliens, Robots, or Monsters

Sharp observations from Christine Prevas about how sci-fi uses nonbinary gender to emphasize the non-human nature of non-human characters — and what that means for very human nonbinary readers.

Here, in a novel that isn’t about gender, a character is calling attention to the aching lacuna left by the binary question, “are you a boy or a girl?” They are finding an alternative answer. When Soro answers, I’m a Sunai, they are finding a new way to answer the question.

I’ve answered the question this way, too. A young child at my place of work once asked me: are you a boy or a girl? I panicked and answered: I’m a librarian. Can I help you find something?

For Libraries, "the Customer Is Always Right" Might Be Wrong

One thing’s clear in this feisty short essay by librarian Kristen Arnett: patrons should never be allowed near the copy machine. On the challenge of keeping end goals in mind while working on the front lines of circulation.

Circulation is the face of the library. It’s a public-interaction job, which means customer service, which means you better be able to smile at someone even if they’re yelling about how they broke the copy machine by sticking newspaper in the feed tray “just to see what would happen.” It’s a glamorous gig, circulation, and so much of it is dealing with people getting pissed off because they can’t have the thing they want exactly when they want it.

"We are New York indie booksellers"

Franck Bohbot’s portraits of New York’s independent booksellers (taken with partner Philippe Ungar, whose interviews will be published alongside the photographs in a forthcoming book) are careful and quirky. These aren’t Instagram-friendly images of smiling booksellers with piles of gleaming stock; the photos are oddly lit and oddly proportioned, serious, almost somber. Bohbot captures the pride these booksellers take in their stores — and the weight of running a small, stubborn business in an industry crowded by Goliaths.

The spectacular power of Big Lens

If you thought Big Tech was creepy, meet Big Lens — the newly minted megacompany that’s mediating the way we see the world.

Over the coming decades, EssilorLuxottica will have the power to decide how billions of people will see, and what they can expect to pay for it. Public health systems are always likely to have more urgent problems than poor eyesight: until 2008, the World Health Organization did not measure rates of myopia and presbyopia at all. The combined company can choose to interpret its mission more or less however it wants. It could share new technologies, screen populations for eye problems and flood the world with good-quality, affordable eyewear; or it could use its commercial dominance to choke supply, jack up prices and make billions. It could go either way.

Whatcha Reading, Nicola Griffith?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Nicola Griffith is the author of seven novels. Her most recent, So Lucky, is being released this Tuesday, May 15th. She'll be making two appearances — the 15th at Phinney Books, and the following night, May 16th, at the Elliott Bay Book Company. Appearances by Griffith are rare, even in her home town, so get out and take advantage! But if you miss her (or, make it but want more of her voice in your life), be sure to check out So Lucky on audiobook — her debut as a narrator. Maybe she'll narrate the next Hild book, Menewood, when that is released, as well...

What are you reading now?

I always have several things on the go, for different times, moods, and contexts.

The book I really want to be reading all the time right now is nonfiction: Building Anglo-Saxon England, by John Blair. But I'm not reading it at all, just glancing at it longingly and waiting for a book stand to arrive: it weighs about 5 lbs. I wish I were exaggerating, but I'm not. It's a massive, heavily illustrated offering from Princeton University Press that brings together the latest understanding of the Anglo-Saxon built environment and its inhabitants. But, oh, if you like the details in Hild about how the A-S world worked — and big hands and biceps of steel, or, y'know, a bookstand — you'll eat this with a spoon.

To read on my phone or for ten minutes with a cup of tea, I have Passing Strange, a novella by Ellen Klages set in in 1940s San Francisco, full of magic, pulp fiction cover paintings, and lesbians in love. Currently shortlisted for the Nebula Award.

To read aloud to Kelley at night, I have Patrick O'Brian's HMS Surprise, third in the Aubrey/Maturin series. These are magnificent books: Jane Austen on a ship of war, with the humanity, joy and pathos of Shakespeare — not only brilliantly written but absolutely fabulous to perform.

What did you read last?

Coming in July The Mere Wife, Maria Dahvana Headley's astonishing reinterpretation of Beowulf. This is Beowulf in suburbia—epic, operatic, and razor sharp. It uses Beowulf’s three-part structure and a fascinating take on Old English traditions of animism to create a story not of a thick-thewed thegn but of women; women at war, literally and figuratively. It is Maria Dahvana Headley’s women who are the givers of grief, the dealers of doom.

Gods, Monsters, and the Lucky Peach, Kelly Robson. This is another novella, time-travel ecofiction in which physically modified humans from a post-ecocatastrophe future go back to Ur to sample the flora and fauna. Things do not go as planned, and Robson doesn't flinch from dramatic choices.

What are you reading next?

A Woman, In Bed, Anne Finger. I met Anne last month and loved the bit she read aloud. Excitingly, it's published soon after my novel, So Lucky, which means for the first time (to my knowledge) two #CripLit novels that pass the Fries Test are out within a month of each other. I am thrilled!

The Best Bad Things, Katrina Carrasco

I read 5 pages a couple of months ago and it's very promising: a supremely visceral novel set in the late nineteenth-century Pacific NW in which a woman disguises herself as both a man and woman to investigate opium smuggling. Seattle resident Carrasco is not afraid to take risks. Now that I have an ARC, I look forward to the rest. Out in November.

The Consciousness Instinct, Michael S. Gazzaniga

I'm dying to see how Gazzaninga tackles the question of consciousness and the relationship between brain and mind. Is consciousness an instinct? I hope to find out.

The Help Desk: Are you e-xperienced?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Have you ever used an e-reader? Why or why not? And if so, what did you think?

Jasmine, Fremont

Dear Jasmine,

Yes, I was gifted a Kindle years ago. I used it for a bit. It was fine for reading romance novels on the beach during vacations and for loading up all of the books I needed for graduate school (I have dual master's degrees in Barbie Architecture and American Cheese History from Devry), but overall I found it underwhelming.

Forgive the esoteric academic reference but e-readers are the EZ Cheese of books. They do nothing to enhance the reading experience, they just repackage it in a silly way under the guise of "progress." What you lose are books lining bookshelves, conversation pieces, petite packages of knowledge and creativity ready to lend to friends and people you'd like to impress.

Part of the pleasure of reading is the smell and the tactile feel of turning pages. Without those sensations, when using an e-reader, I experienced the impatience that non-readers must feel when trying to get through a book. I skimmed more and retained less.

I forgot to update the software on my Kindle way back in 2016, when Amazon insisted, so now it's worthless as an e-reader. It functions as a $300 bookmark for an antique dictionary. And although most iterations of Barbie would not be caught dead reading, it also exemplifies Brutalist Barbie architecture: inside the Kindle's pragmatic design and bleak interface lies the weak beat of human ambition, the unfilled promise of unlimited knowledge, the hope for something better. Another failed utopia.

Kisses,

Cienna

Bruce Haring at Deadline reports that Adam Parfrey, the publisher at Port Townsend independent press Feral House, has died.

Parfrey's anthology Apocalypse Culture was the first countercultural text I ever encountered; it taught me how to cultivate critical thought at a time when the rise of institutional and corporate power was unquestioned by the mainstream media. I know I am not alone; the Apocalypse Culture books specifically, and Feral House's books in general, provided a window into a world that was weirder, more passionate, and more intellectually curious than most of the other books you could find at a Borders or Barnes & Noble at the time.

I hope Feral House continues sharing Parfrey's vision with the world for years to come. There's still a need for his outsiders' perspective — in fact, Parfrey's eagerness to question authority is more necessary now than ever. I owe him a tremendous debt of gratitude, and so do tens of thousands of readers around the world.

As I wrote last year, Seattle poet Joan Swift was an inspiration to many poets — particularly writers who were older or otherwise outside what's perceived to be the so-called literary mainstream. So it's fitting that Poetry Northwest created a prize in her memory that honors those writers. And today, they've announced the Joan Swift Memorial Prize's very first recipient:

The editors of Poetry Northwest are pleased to announce the recipient of the first ever Joan Swift Memorial Prize, awarded to a woman poet, 65 or older, currently residing in the Pacific Northwest. The winner is Anne Griffin, of Portland, OR. Her poem, “My Father, Leaving,” receives $500, and will appear in the Summer & Fall 2018 issue of Poetry Northwest.

Congratulations to Griffin! We look forward to this prize spotlighting the work of older women poets for many years to come.