First Confession

The color in the room was yellow.

I don’t know if I knew then why,

or that yellow is as much the color of nerves

as it is of cowardice, as I stood stiff-straight

in front of Father Panda and examined his face.

It was wide, porous, ruddy, full as a moon beneath

a wave of curly hair the color of the pews.

We both wore white, he in his vestments,

me in my dress, all decked out

with the things I knew I must have done wrong.

From the vestibule, the smell of incense wafted in.

Outside the room I could hear the sound of children

trying hard to be quiet. A bit of holy water

splashed from someone’s finger to his forehead.

I was bad. I was definitely bad. I thought. The bell

tolled. Father Panda’s wide face split into a smile.

I amused him with my silence. I was not a sinner,

after all — was it possible? No. I gulped, stammered,

dug in: “I can’t think of anything.” That was the sin.

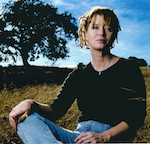

The witches are coming, and they're bringing Lindy West

Frankly, she had us at "I'm speaking"; by the end of that string of phrases, we were ready to see her twice. These are trying times, and they deserve to be skewered, as only Lindy West can. Get tickets here or get more information on our sponsorship page.

Many thanks to returning sponsor Northwest Associated Arts for supporting the site and for putting events like this in front of our readers. If you're interested in joining our community of sponsors, check out the last dates available in the first half ot he year. We'd love to meet you.

Photo credit: Jenny Jiminez.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from April 9th - April 15th

Monday, April 9: Make Trouble Reading

Cecile Richards is president of both the Planned Parenthood Federation of America and the Planned Parenthood Action Fund. Her book Make Trouble is about her life - protesting the Vietnam War as a child, growing up as the daughter of fabulous Texas governor Ann Richards, and fighting regressive anti-woman forces in her role at Planned Parenthood. Tonight, she'll be in conversation with Lindy West, who is having a big week — West is also interviewing author Samantha Irby at University Temple on Wednesday, April 11th, and she's headlining at Benaroya Hall on Sunday, an event that is our sponsorship this week. University Temple, 1415 NE 43rd St,634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, $27.

Tuesday, April 10: Lawn Boy Reading

You'll be hearing more about Jonathan Evison's new novel Lawn Boy around here in short order. It's a book about a poor young man who barely makes a living as a landscaper on Bainbridge Island. Tonight is Evison's Seattle debut of the book, which is always a special event. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, April 11: Parts Per Million Reading

See our Event of the Week Column for more details. Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, April 12: Chemistry Reading

Weike Wang's Chemistry was one of the most critically praised novels of last year. Finally, the coming-of-age novel is coming out in paperback. Wang will be discussing the book's success and its themes of race, success, and indecision with Seattle author Kristen Millares Young. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Friday, April 13: Jasmine Gervais

Seattle-area painter, sculptor, and passionate feminist rights activist Jasmine Gervais examines ideas of sexuality and society in her work. Among other works she's created, she has made these funny and oddly touching tableaus of people in the midst of what appear to be half-clothed, drunken hookups. The advertising copy for this event invites you to come see and discuss her work in "an anti-gravity, gloriously inclusive environment." Greenwood Space Travel Supply Co., 8414 Greenwood Ave N, https://www.greenwoodspacetravelsupply.com/, 6 pm, free.Saturday, April 14: Grief and Release: Poetry as Elegy

Hugo House's craft talk series continues with poet Ada Limón, who will celebrate National Poetry Month with a discussion about poetry and grief. Limón has a new book of poetry out this summer, and it seems quite possible that she might debut some of that work here at this reading tonight. Frye Art Museum. 704 Terry Ave., 622-9250, http://fryemuseum.org, 7 pm, $15.Sunday, April 15: Examining Our Earth Through Poems

April is National Poetry Month. April is also the month in which Earth Day happens. This event at Open Books combines those two worthy pursuits by asking poets to discuss "what environmentalism looks like and how it intersects with other injustices faced today." Seattle's Youth Poet Laureate Lily Baumgart hosts a reading and discussion about sustaining our planet featuring local talents Aisha Al-Amin, Quenton Baker, Namaka Auwee-Dekker, and Sierra Nelson. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 5 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Parts Per Million reading at Third Place Books Seward Park

Portland author Julia Stoops started writing her debut novel Parts Per Million in 2002, when liberal America was trying in vain to keep President George W. Bush from going to war with Iraq. It's hard to recall now, after Occupy and Black Lives Matter and the Women's March and the March for our Lives, but 2002 made activism feel like a fool's errand. It seemed - to me, anyway, and to many of my friends - that the age of protest had passed, and that the people were powerless in the face of such relentless evil.

Parts Per Million is a kaleidoscopic novel composed of dozens of short chapters from the perspective of three activists in this time of little hope for activism. They're all compelling characters. Jen is an embittered computer hacker. Irving is a former soldier who dedicates his time to fighting the system he defended. John is optimistic but becoming exhausted that they're not making any progress. They record a radio show, but they're not sure anybody's really listening. They don't know if anything matters.

"The Marysville firebombing was the start," Ian warns us at the beginning of the book, "But what blew up in our faces that year was bigger than that blaze." The three activists find themselves at odds, serving as a kind of microcosm for the way progressives always tear themselves apart.

Parts Per Million is an ambitious first book: it's a thriller and a novel about a friendship in peril and it's a critique of protest culture and it's a love letter to those who are willing to earnestly fight for what they believe, even when it seems that everyone else has given up. (In case you were wondering where Stoops's loyalties lie, the book is dedicated to "environmental activists of every stripe," because "One day you will be considered heroes.") Fans of Edward Abbey's seminal The Monkeywrench Gang will enjoy the way Stoops rethinks and enlivens the concept for a new generation.

This Wednesday, April 11th, Stoops will read and take questions at Third Place Books Seward Park starting at 7 pm in the Seattle debut of her book. If you've ever felt helpless in the face of a giant, uncaring machine, you'll recognize something of yourself in Parts Per Million, and you'll likely find kindred spirits at the reading for the book.

Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for April 8, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Comic book artist worked on Wonder Woman & Thor, now homeless

There’s not much new in this Weekly Standard article on homelessness in Seattle for any resident of “this picturesque city nestled on Puget Sound” (ahem) who’s paying attention. Still, it’s a good stop against complacency, to see ourselves through an outsider’s eyes — and especially the casual mention of Seattle’s “energetic NIMBY movement.”

For book lovers (that's you), this piece by Ryan Krull on the intersection between libraries and homelessness in St. Louis is also interesting, especially in the wake of the recent sharps waste kerfuffle at Seattle’s library system. There’s a NIMBY element hidden in both, if you look close enough. (Spoiler: you don’t have to look that hard.)

And here’s one last angle: award-winning comics author William Messner-Loebs, one of the artists credited in Wonder Woman, is homeless, thanks to a string of bad luck and the absence of any reasonably functioning safety net for writers and artists. Derek Kevra wrote about his love for Messner-Loebs’ work. I don’t have a neat takeaway for this one (though I bet co-founder Paul Constant does), except to say that all three of these pieces reflect a misplacement of values that might be worth taking a cold hard look at — before it’s too late for us to make a different choice.

I don’t remember 6-year-old me reading that story line, and I don’t remember how Dad handled it (Bill was curious about this) but I remember the cover. And I remember his name on it.

I sat there in silence for a few minutes.

I don’t know what I was hoping for but seeing his name hit me like a ton of bricks. Those comic books created some of my favorite memories as a kid and Bill wrote them. He created, fought for and worked on those stories and I read them with Dad while drinking a Cherry Pepsi.

Now the man who gave me those memories was living out of his car. I’d love to say at that moment I jumped up with a specific plan to help him get on his feet but in reality, I sat there and cried.

Dark Matters

Abe Streep’s profile of the Arlee Warriors, the championship-winning high school basketball team from the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, has gone everywhere this week. It’s a pretty piece: inspirational, touches on some tough issues, lightly. It makes us sad in that way that we’re all okay with — the non-bleak, mostly hopeful, bearable kind of sad.

Which is a bit of a tipoff that the ways in which Alicia Elliott’s essay about Canada’s failure to convict the adult/male/white killers of two Indigenous teenagers makes you feel sad may not be bearable. Her central metaphor — racism as the unseeable thing that deforms the universe we live in — is apt and powerful, and her writing is personal and relentless. This deserves to be read just as widely, starting with you.

Then I remembered what Gerald Stanley’s lawyer said about Colten’s death in his closing argument: “It’s a tragedy, but it’s not criminal.” I remembered the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities trying to push for stronger self-protection laws while simultaneously denying the impact the Boushie killing had made on this decision. I remembered the white people on Twitter flooding Indigenous people’s accounts with racist slurs; claims that Stanley was acting in self-defence; claims that Colten was a criminal who had it coming; that Stanley’s white lawyer dismissing all visibly Indigenous people from the jury as soon as he saw them was not racist; that an all-white jury finding Stanley innocent of any wrong-doing when he shot Colten point-blank in the head was not racist; that none of this was racist. I remembered all the times I’ve pointed out racism in my life and the white people around me claimed I was imagining it. I remembered that, eventually, I started to wonder if I really was imagining it. I am always made to feel as if I am imagining it.

The Rules of the Asian Body in America

Finally, one from Roxane Gay’s new venture, the month-long pop-up magazine Unruly Bodies: Matthew Salesses on what happens when his Korean wife is diagnosed with stomach cancer after the birth of their second child. While the safety net of American health insurance shreds beneath her, the new and uncertain immigration laws tangle themselves around the family’s neck.

(Full disclosure: clicking this link will burn one of your three free reads on Medium this month. If you care about that sort of thing.)

I was among the largest wave of Korean adoption in the late 1970s and early 1980s. My adoptive parents are Catholic. (My father was on his way to becoming a priest when he married my mother.) They believed the best way to be good Christians was to erase my body from contention. According to my father, they still consider me not Asian at all, “only their son.” In order to follow the rules of family, my body had to be an exception to the rules.

It was in search of my body and its rules that I found Cathreen in 2005, when I went to Korea believing that I had no history at all. She introduced me to myself. Four years later, she immigrated to America, married me, and got her green card, putting her trust in rules that historically distrusted us.

Whatcha Reading, Jonathan Evison?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Jonathan Evison's latest novel Lawn Boy has just come out. Join him this Tuesday at University Bookstore for a discussion and book signing.

What are you reading now?

I'm currently reading Memento Park, which is a supremely assured, elegantly crafted second novel from a former book blogger Mark Sarvas (The Elegant Variation). Mark was always a very tough critic, not unlike Peter Bogdanovich, and like Bogdanovich, Sarvas has put his money where his mouth is and delivered a fine piece of work about fathers and sons, art, and family revelations. It's totally unlike any book I would ever write, which is another reason I'm digging it.

What did you read last?

I just finished (for the second time!) a spectacular self- published novel called Jimmy James Blood by Missy Ann Peterson. Missy comes to the literary world out of nowhere. Last I checked she was working on a road crew in Montana. It's obvious the novel is born of hard-bitten experience. Reading Jimmy James Blood is a visceral and stirring experience from the very first sentence. Missy goes from lyrical to gritty in a single turn of phrase, and she does it over and over again. I am currently lobbying publishers to grant this book the release it deserves.

What are you reading next?

Sigh. So many choices, so little time. As you might imagine, my "blurb pile" is halfway to the ceiling. I'm not even sure what's next in the queue, but in the spirit of our forthcoming NHL franchise, I'm hoping to soon read an early draft of Jarret Middleton's Heart of Winter, which is destined to be the definitive hockey novel of the twenty-first century (not hyperbole!).

The Help Desk: On gender-swapping the classics

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I had some friends recently talking about how great Columbo was, and that led to wondering if that character could be played by anybody but Peter Falk. Notably, if we rebooted Columbo, what woman could play the detective?

It led me to wonder what other books would be amazing with girls or women as the protagonist. Haden Caulfield, say. Call me Isabel. Phyllis Marlow. See where I'm going? What book would be just as impactful and great if we gender flipped the lead? I'd love to hear your thoughts.

Diane, Brentwood

Dear Diane,

Your question was a great exercise in considering my personal favorite novels and why they stuck with me. Many of my favorite male protagonists could easily swap gender without significantly compromising the story – Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit, Pip in Great Expectations, Ignatius Reilly in Confederacy of Dunces, Tom Sawyer in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, all of the flies in Lord of the Flies. The same cannot be said of my favorite female-driven novels: Anna Karenina, Pride and Prejudice, Kindred, The Scarlet Letter — even short stories like "The Yellow Wallpaper" or "The Waltz."

The signifiant difference is that, at least with regards to the stories on my list, novels with male protagonists are concerned with finding themselves, coming of age, or embarking on grand adventures that pit themselves against Society or Mother Nature Herself, while books with female protagonists (or people of color) are fundamentally about navigating society in very mundane ways: by making an advantageous marriage, being taunted by home decor, or simply by surviving. These are books that could not be written if the protagonist were a white male, because white males aren't burdened with the same societal constraints that women and people of color are.

I don't often get into arguments about white privilege – or even more specifically, white male privilege – for the same reason I refuse to speculate on the shape of the earth: it is an exercise in stupidity for the very stupid. The earth is round and white privilege/white male privilege exists, period. Great works of literature, much like photos of our orb-shaped earth, have illustrated this over and over and over again.

Fortunately, some authors are already rewriting classic tales to reflect more points of view than just the dominant. For instance, Fifty Shades of Grey is really just Of Mice and Men with a smarter hot chick and spankings. Take comfort in this.

Kisses,

Cienna

Book News Roundup: City Arts wants you as a member

The West Seattle Food Bank is "in desperate need of children’s books and board books" right now, according to the West Seattle Blog. Donate if you can!

The Orcas Island Literary Festival is coming up in just over a week! Authors include Kim Fu, Adam Johnson, Robin Sloane, and Victor LaValle. Tickets are still available.

Susan Fried at the South Seattle Emerald reports that Real Change magazine is publishing a resource guide for Seattle's homeless population:

There are over 300 services listed in the guide. The print run of 40,000 copies will be available at over 75 locations around the city including through human service agencies, first responders, and the Seattle Public Library. Both the Seattle Police and King County Sheriff’s Departments will receive copies to assist people in finding needed services. Real Change vendors will also have access to a few copies per day to share with people in need.

CROWDFUNDING ALERT: City Arts magazine is shifting to a nonprofit, and they're running an Indiegogo campaign to make the leap. The monthly magazine is seeking members to help support a "more robust digital footprint" and "more events." This city is seriously lacking in multidisciplinary arts coverage, and losing City Arts would be a disaster. If you can, kick in.

CROWDFUNDING ALERT, PART DEUX: In more fun crowdfunding news, Emerald City Comicon founder Jim Demonakos is Kickstarting an updated version of those old-school spinner racks that drugstores used to sell comics from. "The Classic Comic Book Spinner Rack" will come in black and white, it will hold all types of comics, and it will be "whisper-quiet." This project has already been funded, but you can buy your rack over here.

El Diablo Coffee, the delightful coffee shop right next to Queen Anne Book Company, has to move. Read the whole frustrating tale at Seattle Eater. No trip to QABC is complete without a short, sweet Cuban coffee from El Diablo.

At Library Journal, Matt Enis offers a librarian's perspective on Amazon's creepy always-on Alexa devices.

Contois does acknowledge that these devices also present privacy and security concerns that new adopters may not fully understand. “We make them aware that they may want to become more knowledgeable about that,” he says. “We do ask patrons, before returning them to the library, to reset everything to the factory settings.”

- Every year at this time, comics shop retailers gather to discuss how their industry is doing. Heidi MacDonald at The Beat reports that this has been a tough year for the industry:

Every retailer I chatted with knew of a shop that had closed, often down the road. The reasons aren’t always simple, though. This shop had its lease raised. This shop expanded too fast. That one’s owner just decided it was time to pack it in.

- Oh my God, please help Project Gutenberg redesign its site. What a nightmare that website is.

Portrait Gallery: Infinite Potential

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Simple tools

Write a list, write a poem, write a tenet, write a letter, write a song, doodle a picture of your dog, draw a map, make a mark.

Kissing Books: the coded dress

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

This month I intended to write something frothy about clothing in romance. About the linen and muslin and silk of historicals, the wool suits and high heels of contemporaries, the uniforms of sports romances, the dragon-scarred leathers of fantasy romance, or the nano-regulated synthetic fabrics of the future in SFR (sci-fi romance, for those in the know). But every time I reached into the froth I found a chunk of solid substance underneath that brought me up short.

Consider the dress code.

Fashion, we tell our youth, is a frivolous matter. It marks you as shallow and materialistic (if you’re read as female) and potentially queer (if you’re read as male). It is classed as neither a science nor an art; at best it’s a hobby, harmless but ultimately unimportant.

And we will ban you from school if you do it wrong.

Even the definition of “wrong” depends on so many different factors: geography, audience, time of day, social group, gender, race, religion, body shape, ability. Anyone who has ever overdressed for a party knows how nebulous the rules are, and yet how painful it is when you fail to follow them. Fashion in fiction is even more fraught, because it’s never an accident: it’s chosen (by the author, if not always by the characters), so it can only add meaning. The billionaire’s meticulously tailored suit advertises his power and wealth. The debutante’s pristine gloves are there to be slowly undone, one pearl button at a time.

But this meaning is as slippery as the rules: take, for instance, a red dress. The shy heroine could wear it to show her newly found confidence, which the best friend-turned-lover hero has been helping her build up — or a brash no-nonsense heroine could wear it because she knows she looks awesome and she wants to show the enemy-but-not-for-long hero what he’s missing, the jerk. If the Other Woman is wearing a red dress, it could show she’s sexually aggressive — or it could be because it’s an expensive couture number that flaunts her social status and how faux-perfect she is for our wealthy hero (unlike our poor but authentic heroine). There’s even a famous historical romance where it’s the hero wearing the red dress (Anna Cowan’s Untamed). Clothing motifs, it turns out, are endlessly fluid and adaptable, even when they’re using the same general pattern. I could probably write a fifty-page dissertation just on gloves in historical romance, without ever having to look beyond the books in my personal library. And that’s not even going into the fact that my library is very Western-centric (I’m working on it!) and there’s heaps more possible interpretations when setting romances in non-Western cultural traditions.

Because clothing is never just about fabric, or even just about fabric and bodies. The overall look of a garment depends on the shape and color of the body wearing it, yes — but it also depends on the eye of the beholder, to a degree we don’t always acknowledge openly (unless we’re yelling rebuttals at Project Runway judges because seriously, are we even looking at the same pieces sometimes???). Fashion is a bit like a book, in that sense: one person puts it together, and another person looks at it, and the artistry happens in the space where the building and the looking connect. Fashion is more than just a medium: it’s a language, capable of everything from bawdy limericks to epic tragedies to ephemeral, mutable slang.

This month’s books have a seamstress in Belle Époque Paris, a fat fashionista in modern-day Manila, a runaway Regency bride whose escape ruins more than her gown, a nonbinary Regency heroine who gives up gowns entirely, and a midcentury model for a haute couture house. For some characters, clothing is a business; for others, a vital medium for self-expression and identity. It may be fun (Lady Crystallia’s lavish frocks, Martha’s chic officewear, Robin Selby’s piratical lace cuffs), but it’s never, ever frivolous.

Recent Romances:

The Prince and the Dressmaker by Jen Wang (First Second Books: historical YA nonbinary/f graphic novel):

When my print copy of this lovely book arrived in the mail, it caught Mr. Waite’s eye. He picked it up, flipped to the back, gasped audibly, and slammed the book shut again. “You are going to love this,” he said fervently.

I told this story to a friend who’d given the book five stars. She said: “I know exactly what he was looking at. And yes, you’re going to love it.”

Reader, they were right. I knew the page as soon as I reached it. And heaven help me, but I clapped a hand over my mouth and sobbed aloud in such pure delight that I’m crying a bit right now even thinking about it.

When I reached the end, I went right back to the beginning and read it a second time straight through. It’s that good.

I am now ravenous for other people to read this book. Part of me wants to stand outside on the lawn a la Lloyd Dobbler, but instead of that boombox I’d be holding up a blown-up image of one early moment from page 50 to 51. Partly it’s because this story hits so many of my personal YES PLEASE buttons — seamstress heroine, arranged marriages, historical Paris, fashion as art, queer identity, characters in disguise — but also because it’s just such a beautiful, detailed, and kind piece of work that it feels like a gift Jen Wang has made for all of us. Keeping it to myself feels positively selfish.

Our heroine Frances is a gifted young seamstress working too hard for a thankless boss in Belle Époque Paris. One shocking dress for a prickly client gets her fired — but it also gets her noticed by Prince Sebastian of Brussels. Sebastian’s parents are seeking a princess to betroth him to, but Sebastian would much rather be putting on a red wig and a stunning gown and dazzling Paris as Lady Crystallia, everyone’s favorite fashion trendsetter. The two become partners in couture, best friends, and maybe something more — but political marriages, commercial opportunities, and the constricting nature of secret identities threaten the bond between them.

It may be the happiest happy ending I have read in some time. Plus a rich and sophisticated color palette, dazzling gowns, lovely organic inky brushstrokes, and a bonus feature at the end on the artist’s process that I found absolutely fascinating.

If the Dress Fits by Carla de Guzman (Midnight Books: contemporary m/f):

It’s a good thing I read this book in digital form, because if I’d been reading it in print there’d be drool stains on every page. Romance novels and food often go hand in hand (check out reviewer Elisabeth Lane’s marvelous Cooking Up Romance, for instance) but this book takes it to new heights.

And cheese hopia and tarragon tea aren’t the only things to yearn for in the pages of this Philippines-set romantic comedy. Our hero Max is a tall, shy, bookish veterinarian who’s so achingly in love with our narrator heroine from the beginning that at times I had to put the book down just to catch my breath. I love a good unrequited plotline, and this one is particularly stunning. Heroine Martha, meanwhile, is distracted from recognizing Max’s feelings (and her own, aaaaaa) by her demanding family and her self-consciousness about her size and her helpless crush on the gorgeous Enzo, her former theater friend — who just happens to be newly engaged to her perfect, petite cousin. And of course they want Martha to be the maid of honor! And do all the party planning!

This story really knows how to twist the drama knife without going over the line into excruciating, and if Martha is a little frustrating at times, well, so is Emma Woodhouse. This is also a book with a fat heroine that’s realistic about shame and microaggressions without making her weight into The Entire Issue of her life. Martha doesn’t have to learn to love herself — but she does have to learn to tell people that she loves her shape, and to imagine that other people might love it too. It’s the kind of book where everyone is perfectly imperfect, which I found delightful even though I wanted to shake every character at least once when they were being stubborn or scared or short-sighted.

Don’t read when hungry. You have been warned.

”Because I loved you,” I said to him. The words spilled out of my mouth before I could stop them, like the beads on a necklace that had snapped. They scattered everywhere, and it was impossible to catch them all now.

A Duke in Shining Armor by Loretta Chase (Avon: historical m/f):

The beginning of this book is a masterpiece in how to start at the latest possible point in a story and let the characters’ actions reveal who they are.

We begin at the wedding. The groom, the Duke of Ashmont, is drunk and growing belligerent. The bride, Lady Olympia Hightower, also drunk, was supposed to walk down the aisle half an hour ago. The groom sends his best friend, the Duke of Ripley, to investigate — he sees the bride slipping out the back window, and hies off in pursuit. But Ripley never did like to follow the rules, so before long instead of dragging the desperate woman back to the altar he’s aiding and abetting her escape. As the chase extends, that first question — just what is our bride running from? — becomes much less important than the second one: just what does our bride really want?

Like de Guzman’s book it’s all very High Comedy, a Regency It Happened One Night. There are falls into mud puddles, a rescued pup, accidentally seeing each other in the bath, sudden thunderstorms soaking people to the skin, and so on. This lightness masks a surprisingly powerful center, though: Ripley’s fall into love in particular is beautifully done, and the sex scenes verge on poetry (good poetry, I should clarify). Oh, and Ripley is a romance reader: he loves a good pulpy story full of feelings, whereas bespectacled, antiquarian Olympia devises her own library organization systems and cares more for original Gutenberg incunabulae than for novels. After a long stretch where I felt Chase’s books were phoning it in, this book shows up with all the chime and energy of a live brass band.

He was a man, and not a virtuous one.

And so, when he should have said, No, wait, and then added something sensible and correct...he didn’t.

Instead, he walked straight into trouble, the way he always did. He walked the few steps to Doing the Wrong Thing. Then she was in his arms, soft and willing and learning far too quickly how to make him delirious.

And now.

Yes, she said.

Yes, of course. What other choice was there?

Unmasked by the Marquess by Cat Sebastian (Avon Books: historical m/nonbinary):

Three months ago I talked about cross-dressing heroines and Suzanne Enoch’s Lady Rogue. Kit Brantley had been raised as a boy but ends up living as a woman: in Cat Sebastian’s newest, heroine Robin Selby had adopted her late lover’s identity for practical reasons (to protect the man’s sister, who’d been left destitute by the will) but finds that dressing in breeches and waistcoats feels right in a way that gowns and chemises never have. What follows is a long exploration of the difference between what it means to do what’s proper and what it means to do what’s right. It’s a resounding step towards inclusivity for a much-loved but often-dicey romance trope.

Let’s follow Robin’s example and be practical to start: I’ve seen the heroine’s gender described elsewhere as nonbinary, and doing that in a Regency setting definitely presents some challenges. For instance: pronouns. Robin uses she/her for her internal monologue but definitely identifies with gentlemanly things when it comes to manners and mode of dress. One content note: hero Alistair does more than once refer to Robin as a ‘deceiver’ for wearing waistcoats, and pitches a truly epic fit when he first learns of the name-swap. He does not, importantly, have to ‘get over’ the essential fact of Robin’s gender; he’s into both men and women and reasonably comfortable with that. But it was a scene I worried might hit some people more sharply than others, so I wanted to note it here.

Now the subjective stuff: this book is a pleasure that cuts deep. It’s a slow-motion stained-glass heartbreak, all sparkling color and velvet shadow and sharp edges slicing you without mercy. Cat Sebastian definitely draws her couples as strong contrasts, and here Robin is sunshine and springtime, while Alistair is all brooding stodginess and stern propriety. Up to a point, of course. Robin’s charm masks a yawning fear that she has no real identity — no family, no status, and most painfully no name — and this makes her prone to extreme self-sacrifice. It’s easy to give up everything when you feel like none of it really belongs to you. And Alistair’s tendency to go full supervillain to protect his loved ones clearly brings him more devious pleasure than it should: he flings money at problems, wields his privileges like weapons, and at one point actually threatens an antagonist while sitting in a library chair and stroking a cat. He’s been working all his life to be the opposite of his spendthrift, drink-sodden, orgy-loving, bastard-fathering father. Watching him learn to let his human heart show is satisfying; watching Robin learn to really feel as carefree as she pretends is painfully sweet. I devoured the whole thing in a single afternoon and was then good and useless for the next three days. If you need something to give you a book hangover like you’re Bertie Wooster after a bender, this is the book for you.

Alistair walked directly to the stables and was in his traveling chaise within a quarter of an hour. By the time he realized he was still holding the kitten it was too late to turn back.

This Month’s Vintage Harlequin Heroine

Under the Stars of Paris by Mary Burchell (Harlequin Romance: contemporary m/f):

A good category romance has all the effortless, exquisite clarity of a fine diamond: everything that doesn’t sparkle is ruthlessly polished away until only the light is left. This is the oldest romance I have reviewed so far, but even though it was first published in 1954 it fizzes like the cork was just popped. Heroine Anthea is freshly heartbroken and semi-destitute in mid-century Paris; she stumbles into a hair salon to avoid an awkward encounter and lands herself a job as a mannequin (read: model) for the best couture house in France. She steps onto the runway in a dazzling wedding gown — only to see her caddish ex-fiancé there in the front row, with his new bride-to-be! The stakes are personal but they feel infinitely meaningful; this is the kind of book where a spill of Merlot is as good as a murder. Like most categories of the old school, it’s told entirely from the heroine’s point of view, so that we are not even certain of who the real hero is until very nearly the end of the book. (We can be reasonably sure it’s not the caddish ex-fiancé.) It’s all a delightful confection, full of lustrous fabrics, seething jealousies, and shimmering tears.

Also, this book helped fight Nazis.

Okay technically not this book — but its author Ida Cook (writing as Mary Burchell) used the funds from her romance career in the 1930s to fund trips to Germany for herself and her sister. They went ostensibly to see some of the great opera performances of the age. In reality, they were smuggling valuables out of the country to help Jewish refugees, in direct defiance of Nazi law. Britain only allowed immigration for those who had either employment or sufficient funds to support themselves, but Jewish emigrants weren’t permitted to take possessions or funds out of Germany. It was a terrible bind. The Cook sisters would arrive at the border in plain clothing, and leave bedecked in jewels and furs, which they’d return to the owners once reunited in Britain. If any border guards asked why they were so kitted out, they played the eccentric spinsters and said they had untrustworthy relatives at home, so they always traveled with all their jewelry. This worked at least a dozen times, and after the war the sisters were named Righteous Gentiles.

“You are what you do,” Ida is quoted as saying. We should all have such clarity of purpose.

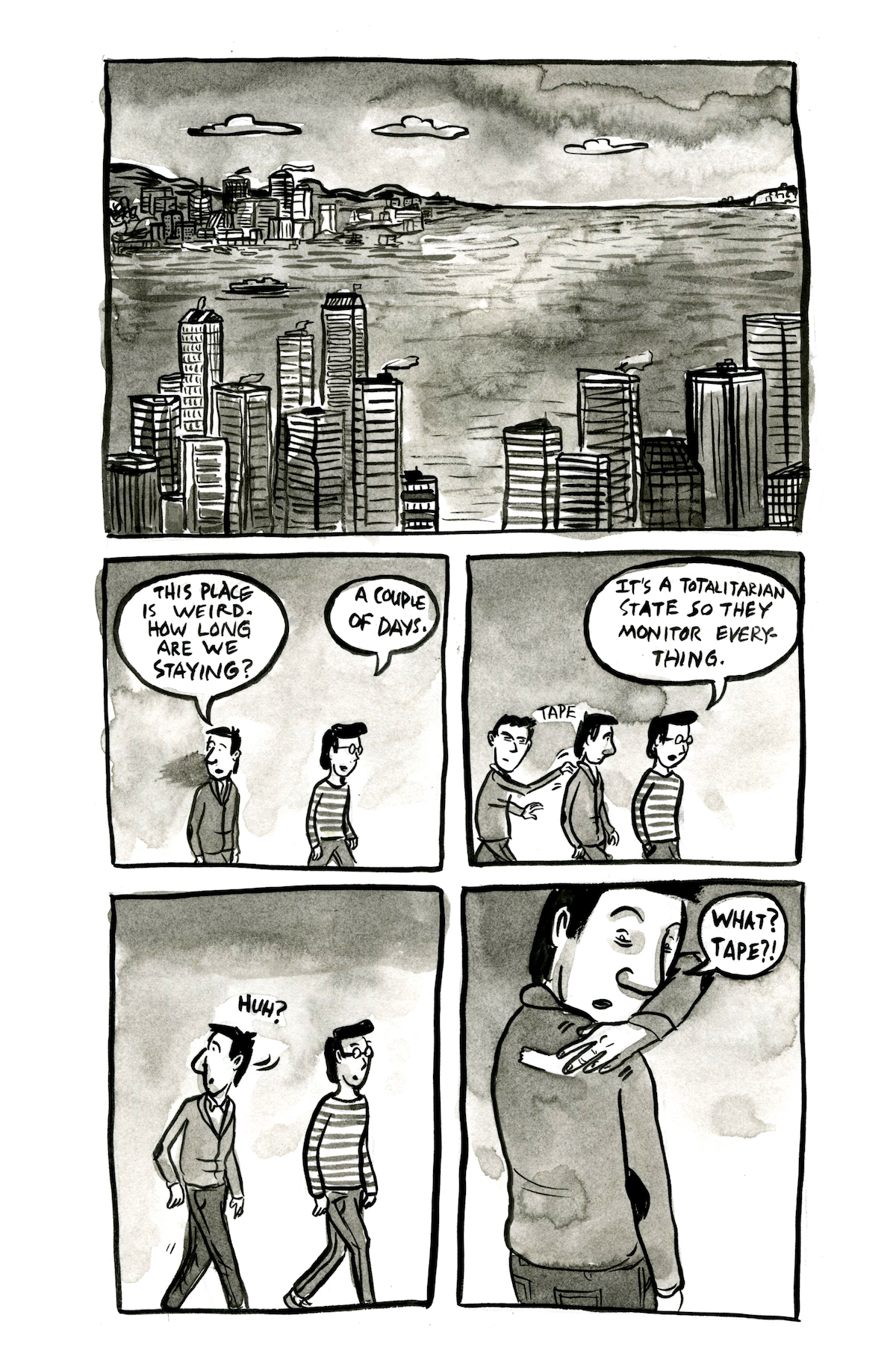

Thursday Comics Hangover: Flipping the bird at dystopian cynicism

I have written before about how much I detest Mark Millar's Old Man Logan story. It's the worst of modern superhero comics: cynical, try-hard, a crass rip-off of a significant pop cultural icon (Millar should have to pay royalty checks to Clint Eastwood for what he did to Unforgiven.) Somehow the series, which imagined Wolverine living in a dystopian future in which the Hulk breeds with his cousin to father a posse of inbred hulkbillies, managed to inspire Hugh Jackman's final Wolverine movie, Logan - a film with all the heart and thoughtfulness that the original series lacked. But that's the only good thing to ever come out of Old Man Logan

Until now. The 33rd issue of All-New Wolverine, which follows the adventures of Wolverine's younger female clone Laura, kicks off a new storyline called Old Woman Laura. Written by Tom Taylor and illustrated by Ramon Rosanas, this series seems to be a direct response to Old Man Logan - a critique and a call to better superheroic storytelling.

I haven't read a single issue of All-New Wolverine before this one, but I could still easily follow the action. Laura - a character that almost everyone knows, thanks to Dafne Keen's heartfelt portrayal in Logan - is a national leader in a utopian future. She's mentoring an even-younger clone of herself, Gabby, who has taken on the Wolverine name for herself. (This is not the ugly, grim Wolverine of the 1990s: Gabby makes her grand entrance in the comic by groaning at the bad guys, "Urgh, you're the worst.") Laura learns that her time on Earth might be numbered, so she decides to fix the two biggest mistakes from her past: give one person a second chance, and kill another person who escaped justice.

Where Old Man Logan was nasty and mean, Old Woman Laura is fun and compassionate. "We fought against greed and hate and fear. And we actually made the world a better place. The heroes won," Laura announces in the first few pages. It's accompanied by a cityscape drawn by Rosanas that shows glimmering towers and huge expanses of vegetation, all in lush shades of green. It's a beautiful world - one that laughs in the face of Old Man Logan's loathsome dustbowl.

Of course, things could go wrong between this first issue and the end of the Old Woman Laura storyline, but Laura's quote above seems to be the mission statement for the book, a refutation of the cynical worldview espoused by Millar in Old Man Logan. Millar argued that even if heroes did their best, they'd still lose because the natural order of things is to decay and turn sour. Taylor and Rosanas seem to take Millar's vision into account, talk amongst themselves, and then reply, "yeah, fuck that." I'm with them.

Shining lights on the dark corners of the internet

The word that set most of the Reading Through It Book Club on edge last night was "transgressive." That word shows up a lot in Angela Nagle's book Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. She quotes Milo Yiannopolous and other alt-right figures who call themselves "transgressive," and she seems to buy into the word a fair amount.

But are the men who call themselves men's rights activists and gamergaters and white separatists online really "transgressive?" If you take them at their word, in fact, they're regressive: they want to return to what they imagine to be the glory days in America, when white men were at the top of the pyramid and everybody else was considered to be a second- or third-class citizen.

But really, it's hard to believe that most of these online trolls actually believe they can turn back the clock to the bad old days. And they don't care about the social norms that they're shattering. They're not transgressive. They're not regressive. The truth is, they just want to blow everything up, just to see if they can.

Kill All Normies is not a very well-constructed book. It's in dire need of some strong editorial thrashing. Nagle inserts her own glib opinions in awkward moments. Her description of the birth of Gamergate contains some serious inaccuracies. One whole misbegotten chapter is devoted to comparing Yiannopolous to Pat Buchanan. A member of the book club bought an edition of Kill All Normies that misspells Barack Obama's first name in the very first sentence of the book. The thing reeks of a rush to publication in an effort to seem relevant.

But here's the thing: one day, someone will write the essential history of men in online culture. The book will cover the birth of 4Chan and Reddit, it will uncover anonymous identities, it will examine the actual real-world percentage of men who take part in these subcultures, and it will chronicle their transition from harmless trolls to gamergaters to MAGA-heads. That book is undoubtedly being written right now, and it will take time to get it right.

For now, I'm happy that Nagle is elbowing her way into the conversation, even if her arguments are sloppy and her thesis is weak. The thing is, many people still don't fully understand or care what online cultures are doing to our men. Average Americans see the words "trolls" or "normies" and they think of harmless nerds sitting in their basements. Nagle's book is at least the beginning of a discussion of how that online hatred - hatred which starts as ironic joking and ends with very real rage - is activating an entire generation of young men, weaponizing their language, and pointing them at any target they can find.

We had a great discussion about Normies last night at Third Place Books Seward Park. We discussed the limits of free speech, the perils of anonymity, the heartbreak of the whole ugly situation. Normies is a hard book to love, but it stirs up some important conversations in the moment.

The Reading Through It Book Club meets next at Third Place Books Seward Park at 7 pm on Wednesday, May 2nd. We'll be discussing The Line Becomes a River, which Donna Miscolta beautifully reviewed on this site yesterday. The book is 20 percent off right now at Third Place. I hope you'll join us.

The mystery of the underlined sevens

Yes, the world is terrible, but every now and then you deserve a good thing. Follow this thread. I swear it's worth it.

So there was a MYSTERY at the library today.

— Georgia | Saoirse (@green_grainger) April 3, 2018

A wee old women came in and said "I've a question. Why does page 7 in all the books I take out have the 7 underlined in pen? It seems odd."

"What?" I say, thinking she might be a bit off her rocker. She showed me, and they did.

Trying to make sense of the border

Published April 04, 2018, at 12:00pm

At the border between Mexico and the United States, lines run much deeper than the surface of a map.

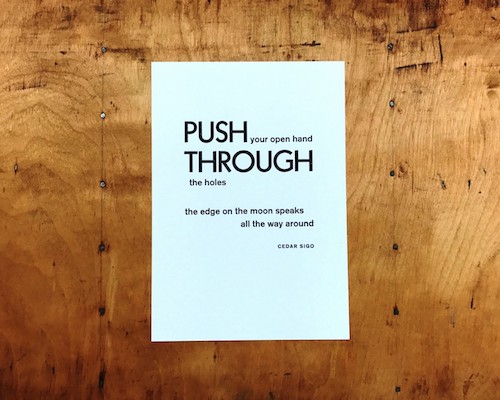

"I think of them as propaganda for poets"

Tomorrow night at Core Gallery from 6 to 9 pm, Expedition Press founder Myrna Keliher will debut On Edge, a month-long show of her series of Broken Broadsides prints.

Over the phone, Keliher explains the project: you take the concept of a broadside (which she describes as "a poster of a poem") and focus it, centering the work on "a few lines broken out and then reframed in a different context." Keliher asks a poet for new work, and then she works in collaboration with the poet, selecting lines and emphasizing words through size and arrangement in "a graphic interpretation of my reading."

These Broken Broadsides aren't intended to be elite collectibles. Keliher wants them to be mass market, affordable, and accessible - "stick it on the fridge," she laughs. "It's all open edition. They're not meant to be very special." Why is that important to her? "I think of them as propaganda for poets," she says, "like breadcrumbs to hopefully get people down a trail of discovery and start reading."

The list of poets who'll be represented at On Edge is impressive: Cedar Sigo, Natalie Diaz, Jane Wong, Shin Yu Pai, Amber Flame, Erin Malone, Elaina Ellis, Leanne Dunic, Tom Gilroy, Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, and Holly Wren Spaulding. Keliher's role in the Broken Broadsides process is an interesting one: she's at once an editor and a graphic designer.

Since she recontextualizes the work, emphasizing different words through graphic design, Keliher is at once supporting the writer and collaborating with them. She says she's still struggling to come to terms with the way the Broken Broadsides changes the poems through their interpretation. "I just got feedback from an author yesterday, saying, 'you just helped me see the poem in a totally different way - in a new way.'"

Keliher still thinks of the process as an active kind of reading. "The lines that I select are, really simply, just the lines that I can't forget - the lines I'd get stuck in my head." From the selection process, she has to then find a way to make those lines work on their own. "I think a lot about stripping away context and I think about surface area and access to lines and entry points in" to the work.

"When I started the project, it felt very radical," Keliher says. "In the literary world and as an editor, it's not something you ever are allowed to do, especially in poetry: you don't change the line break, or make words bigger, or omit lines in between." But even though the poets' response to the Broken Broadsides program has been overwhelmingly positive, "it's still very uncomfortable every time I send one [to a poet for the first time] because it's a major act of trust that they're giving me."

Keliher will be at the opening at Core tomorrow night from 6 to 9, and some of the poets will be in attendance, too. On April 25th at 7 pm at Core, many of the poets whose work was featured in the show will read the complete poems that Keliher excerpted from in an event that should make clear how much collaboration goes into each Broken Broadside.

Consider celebrating National Poetry Month by writing poems

April is National Poetry Month. While for many readers and lovers of poetry this means a bit more time than normal looking through the pages of your favorite chapbook, and lingering in the well-stocked poetry sections of Seattle's many indie bookstores (the best-stocked, of course, being the store that is made up entirely of poetry), if you're a poet (or would like to become a poet), April offers you a compelling challenge: it's also National Poetry Writing Month.

National Poetry Writing Month, or NaPoWriMo (after the better known National Novel Writing Month, NaNoWriMo), has a simple idea: write one poem each day in April. Some participants choose to post their daily output on their blogs, but there's no requirement to share. Just write a poem each day, and you're participating. Even if you never tell anybody. Even if you keep it close to your chest.

Today being April 3rd may be a convenient excuse to not start, after all, you've already missed two days. But consider writing anyway: if you end the month with 28 poems, you're 28 poems ahead of where you were at the start of April. During the month, you may just find the inspiration to write two extra, in any case.

Kelli Russell Agodon, local poet, and cofounder/editor of Two Sylvias Press, had some sage advice for NaPoWriMo participants on her Twitter feed (make sure to click through and read the whole thread).

1) Set a timer for 15 minutes. Tell yourself, This is ALL the time I get and I have to write something. Even if it's not good or long, you have 15 minutes. I'm always amused how I write some of my best poems because I know I need to get somewhere.

— Kelli Russell Agodon (@KelliAgodon) April 1, 2018

It's no secret that we here at the Seattle Review of Books are poetry lovers. We've been publishing poetry each week since our launch, first individual poems in a chain of poets recommending other poets, then starting in 2017 with a Poet in Residence project. If you're looking for inspiration, or good reading, look at our archives.

There are a million topics worth writing about in our bustling and growing city. Someday, maybe we'll get to read a poem that started during this April. We can't wait.

As soon as the man says to the little girl, “I want to touch you,”

a saw stirs up its loud whine

to separate the limbs of the tree

from its trunk.A car stereo begins playing

the entire soundtrack of Good Morning, Vietnamand she hears “hot and wet” “hot and wet” —

“it’s nice if you’re with a lady”and she feels the last, labored breath of Robin Williams

like a dull machete attempting to slice through the swamp grass

as he suffocates himself

outside his closet doorand all of the suicides inside of her

lift their heads and eyes,

like turtles lined up alongside

a creek in which

the bruised, naked torso

of a woman floats by,

her breasts full of gravity, nipples staring off dully to either side

as if she never in her entire life

saw anything that surprised herThe man does not reach out to touch

the girl, though his intention

is like the sheet pulled back

from the skin of that dead body —there’s no stopping it now,

not the unfeeling hands that lift the covernor the grief that will live

forever in the blood of the mother

who stands over her daughter’s torso, the roots of her severed limbsnot even able to speak the words

Yes, that’s her that’s her

One week left to reserve a seat at Anne Lamott's April 8 event

Whether you're a follower of Lamott's Bird by Bird writing guide or a fan of her thoughtful, direct, and funny novels and essays, you should take the chance to see her in person. She's a sharp, warm, and witty speaker and an iconic presence. Get more information on our sponsor’s page, or buy tickets here.

If you're interested in joining our community of sponsors and putting your book or event in front of our readers — check out the last dates available in the first half ot he year. We'd love to meet you.

Photo credit: Mark Richards.