Portrait Gallery: #InternationalWomensDay

For #InternationalWomensDay, a collection of all the amazing, diverse, talented, inspiring women that have run in Portrait Gallery over the past few years.

Click any face to see the painting bigger, with more information about the featured writer.

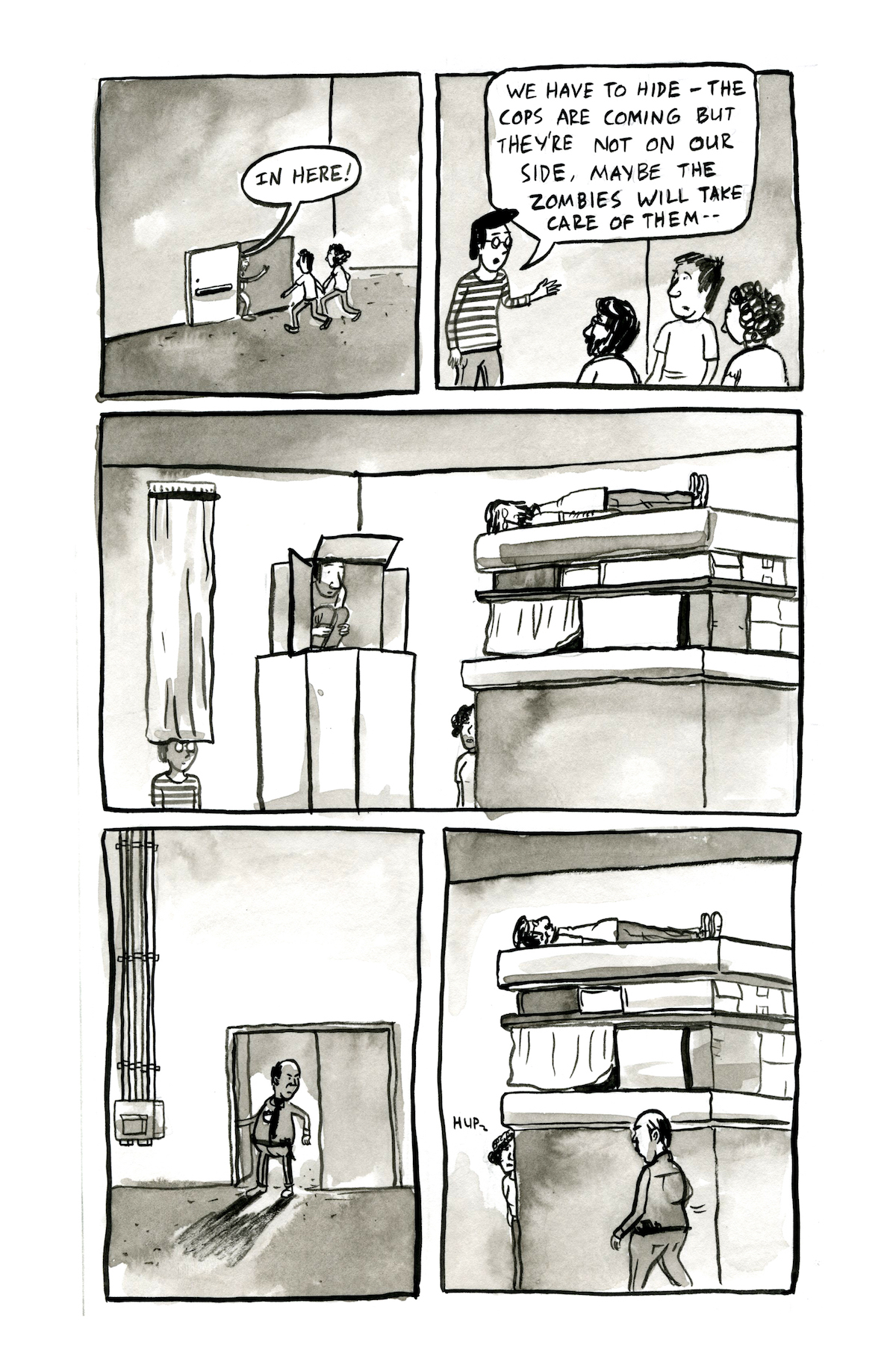

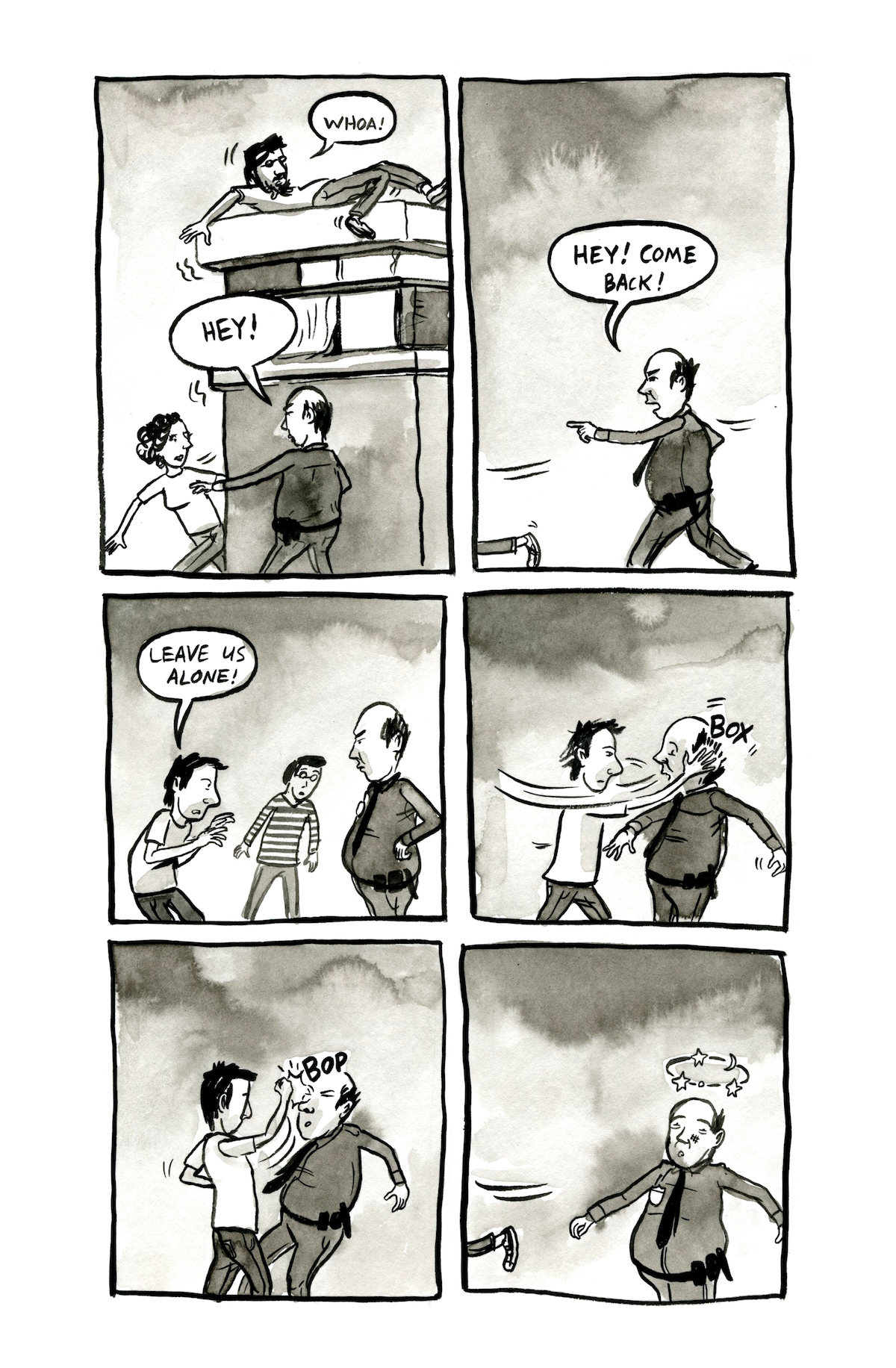

The Future Alternative Past: now with animal pictures

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Dog stars

Like so many writers, I have a cat. Minnie’s her name, and she’s pretty punk. But it’s the dog I didn’t get instead of Minnie I’ve written stories about, and it’s dogs in stories I’m writing about here.

First title in the Table of Contents for my imaginary SFFH reprints anthology About a Dog is Bradley Denton’s fabulous “Sergeant Chip,” winner of the 2005 Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award. Chip, the technologically-enhanced K9 (canine) soldier, narrates a war-time encounter that calls into heart-twisting question his doggish loyalties.

Next would come Kelly Link’s “The Hortlak.” Which maybe isn’t about a dog at all. Dogs are in it. But so are zombies and pajamas. A protagonist working in a convenience store near the “Ausible Chasm” (a zombie point source), yearns after an animal shelter worker who treats the dogs she euthanizes to pre-injection car rides. Just your typical Kelly Link story, and more an exploration of doggishness than of dogs. I still want it.

Connie Willis’s Hugo and Nebula award-winning “The Last of the Winnebagos” would be in there, too. It is clearly and certifiably about dogs — though more specifically it’s about their absence in the wake of a devastating plague, and the lengths people go to so they can hold onto the special relationship we’ve formed with dogs over the last few thousand years.

I’d also need to include some version of Harlan Ellison’s brutal, elegant, and arguably misogynistic “A Boy and His Dog.” That’s the story of 15-year-old Vic and his telepathic canine partner Blood, scavenging their way across a post-nuclear holocaust wasteland. Then, as a restorative, I’d add one of Michael Swanwick’s tales of professional ne’er-do-wells Darger and Surplus. Though Swanwick describes Surplus (full name Sir Blackthorpe Ravenscairn de Plus Precieux) as a bipedal talking dog dressed like a refugee from Mother Goose, he originates in the far-future demesne of Western Vermont, a product of “the gene-mills of Winooski.” For actual fantasy I’d turn to J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series and excerpt a Hagrid/Fluffy scene or two. You remember Fluffy, the three-headed Cerberusesque guardian of the Philosopher’s Stone, right?

Should I likewise excerpt a dramatic passage from Stephen King’s Cujo? I’ll have to read it to find out.

Could be reprinting my own canine horror story would be easier to arrange. “The Tawny Bitch” combines a spectral dog with references to Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s feminist classic “The Yellow Wallpaper” and the recently discovered luridly sensationalist fiction of Louisa May Alcott (kidnapped heiresses! murder! opium!). On the other hand, maybe I’d want to reserve myself a spot instead for “Black Betty,” my talking dog story and homage to one of the smartest, bravest, sweetest Beagle mixes I’ve ever known.

The funnest part of compiling this imaginary anthology would be tying together these very disparate stories — stories differing in subgenre and style and the extent of their engagement with dogs and dogness — with an introduction. Or an afterword. Or both. I’d write about our longest running attempt at interspecies communication, and about the experiments in which we killed Laika and countless, nameless others of our so-called best friends. About the knowledge we’ve won and shared together, and the wisdom yet to come.

Recent books recently read

No one better conveys the thrill of technology’s advance than Daniel H. Wilson, author of the NYT bestseller Robopocalypse and the nonfiction guidebook to an imagined future Where’s My Jetpack? Guardian Angels and Other Monsters (Vintage), a new collection of Wilson’s short stories, showcases his loving ambivalence toward Artificial Intelligence’s potential in particular. Which will we encounter in years to come: the indomitably loyal AI nanny foiling its charge’s kidnapper in “Miss Gloria?” The wide-eyed, impressionable student of “Jack, the Determined?” Or the pitiless soldier-highjackers of “Parasite?” Fast-paced and vivid,Wilson’s takes on these possible scenarios seem simultaneously surprising and inevitable, even as they contradict one another. There’s a depth of feeling arising from the different perspectives he provides: peeking through them, poking around behind, we get a good sense of the endless layers awaiting us in all his work.

Daughters of the Storm (Del Rey) by veteran Australian author Kim Wilkins begins a saga-like series about a royal dynasty ruling a realm reminiscent of the setting for Beowulf. Magic is real, and cares very little whether it’s also clean, convenient, or fair. Five sister princesses struggle for power when a mysterious spell strikes down their father: Bluebell, a born warrior, battles those she suspects of foul play with sword and armor, while Ash apprentices herself to a murderous shapeshifter to learn enchantment’s ways, and Rose weds and then betrays the monarch of a patriarchal neighboring land. The two youngest girls, Ivy and Willow, are the least family-minded and also (not coincidentally) least likeable of this bunch, but even they come across as totally fascinating and believable, thanks to Wilkins’s talented tale-spinning — though I must admit it’s Bluebell who truly won my heart.

Steven Brust’s Good Guys (Tor) leaves behind the vaguely 16th century milieu of his bestselling Vlad Taltos books for modern times. The novel moves from plot point to plot point in the comforting rhythms of a classic thriller, as super spies investigate their organization’s infiltration by baddies. But these super spies only earn minimum wage and supplement their espionage with data entry work. The fact that they’re also trained as magicians does nothing to undermine the necessity for that, and nothing to ensure they’ll win. After all, the bad guys use the same magic. Combining the suspense resulting from this situation and the characters’ ironic commentary, the prolific Brust has written yet another highly enjoyable read.

Couple of upcoming cons

Originally located in Edgar Allen Poe’s hometown of Richmond, Virginia, Ravencon now offers attendees its panels, tournaments, workshops, readings, concerts, movies, and charity auction in Williamsburg, 50+ miles east. With four Guests of Honor — Gaming, Music, Art, and Author — Ravencon emphasizes multiple SFFH modalities while staying true to that ancient con philosophy: the community that geeks together fleeks together. Or words to that effect.

Not far off, in Washington, D.C., the USA Science and Engineering Festival will provide a free weekend’s access to nerd heaven. Pavilions focused on space flight, robots, secret codes, and a wealth of other mind-melting fields of knowledge will entertain participants between stage shows put on by an “explosive chemist,” a “stunt scientist,” and a gentleman respectfully referred to as “Mr. Freeze.” If all this sounds a bit PG-13, that’s deliberate: kids are the Festival’s target audience, though we curious adults are not excluded.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The shaggy depths of outer space

One of my favorites from that time was Jim Starlin's Adam Warlock series, a blessedly self-contained adventure of a space messiah who ultimately had to confront his twisted mature self. (In the 1970s, the Warlock story had a beginning, middle, and end, which was a rarity in serialized superhero comics. In the 1990s, Starlin revived Warlock and put him back on the intellectual property merry-go-round. As far as I'm concerned, the character stayed dead.) The book was visually wild, conceptually bold, and as cerebral as it was fun.

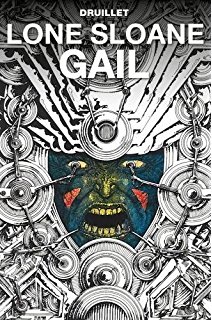

What I didn't know when I first read those cosmic superhero stories was that in 1970s France, an artist named Phillippe Druillet was creating a line of wild cosmic adventures that made its American counterparts seem as pedestrian as a Garfield comic strip.

Gail is a sexy, vivid fever dream, a story of pure evil trying to exert its will on the universe. The panels are angular and detailed down to the very last millimeter: a dimension of fractal skeletons; an emperor languishing on a throne in the aftermath of an orgy; a foreboding castle that stretches miles into the stratosphere, with a real photograph of a woman's face embedded into the front of it.

Our hero, Sloane, is not as grandiloquent as some of Marvel's more pompous cosmic heroes ("Go fuck yourselves!" he roars at the bad guys at one point.) But he's every bit as tenacious, venturing to the land of the dead to confront his opponents and upend the evil empire using just his wits and existential angst as weapons.

I'm not entirely sure what's happening at every point in the story, but that's not a strike against Gail. These cosmic books don't always follow the simple rules of cause and effect. Instead, they're examinations of what it means to be alive, to make moral choices in the universe, to carry the resonsiblity of existing. And Gail commits to the airy spirituality in a way that its American cousins could never manage. You'll never look at Adam Warlock the same way again after you read the adventures of his bonkers French cousin.

Is a company town with no company still a town?

I've already written at length about Amy Goldstein's amazing book Janesville. It was one of my favorite books of last year, a beautifully reported study of the economic turmoil that rocks Paul Ryan's hometown after the GM plant closes. If you want to understand the human cost of the perils facing rural America right now, there's no better book to read — toss aside your Hillbilly Elegy and your New York Times profiles of sympathetic Trump supporters, because you won't need them anymore.

Happily, everybody at the Reading Through It Book Club last night seemed to enjoy and appreciate Janesville. Most were moved by the human drama, and almost all of us learned something new about the desolation caused when a company leaves a company town. Goldstein puts the lie to the idea that retraining can fix everything when massive layoffs hit, and she explains why people can't just pull up roots and move to the city in the face of hardships.

Reading Janesville, the problems that gave rise to Donald Trump became very clear. Less clear, though, were the answers to the problems. We got into a heated discussion about universal basic income, and whether that could resolve the problem of an undereducated population that's been forcefully stripped of their usefulness. Nobody could come up with a satisfying suggestion for how to diversify a rural economy so that a single GM plant's departure can't destroy thousands of lives with a single announcement.

Democratic leaders have let rural Americans down with their inaction. And rural Americans responded by tilting the electoral college in Donald Trump's favor, because Trump was the only candidate who was talking clearly about the problems plaguing rural America. Until Democrats can figure out how to fix these problems — how to strengthen rural economies and provide a sense of purpose for people who have been left behind in the 21st century — the future of this country is in peril.

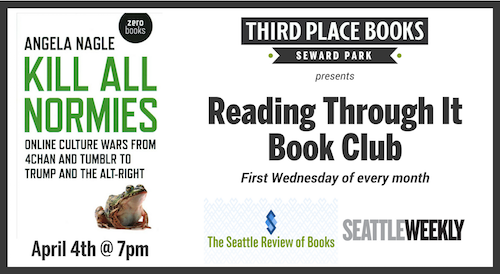

The Reading Through It Book Club meets next on Wednesday, April 4th at 7 pm. The event is free to attend, and our next selection, Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right by Angela Nagle, is now 20% off at Third Place Books Seward Park.

Looking for optimistic sci-fi? Head to the multiplexes.

For years, Seattle author Neal Stephenson has argued that science fiction, in its long lean to the dystopian, has abdicated its responsibility to imagine positive solutions to humanity's worst problems.

Back in 2014, Stephenson joined a community of writers in an anthology of optimistic stories titled Hieroglyph: Stories & Visions for a Better Future. I read Hieroglyph when it was published, but I couldn't tell you now what any of the stories were about. It turned out to be a forgettable collection, and it certainly didn't succeed in its mission to reignite the optimistic golden age of sci-fi that inspired humanity to reach for the stars.

But here's the thing: it recently occurred to me that the optimistic sci-fi that Stephenson was lamenting as nonexistent actually does exist today. We've just been looking for it in all the wrong places.

Last weekend, I watched Black Panther for the second time. It really is more than a standard superhero movie — Black Panther addresses race and politics and commitment to community in a way that most popular entertainments do not. And more importantly, it creates in Wakanda an African nation untouched by slavery and colonialism. It imagines what the African imagination might have accomplished, had white people not ravaged the continent.

I think that Black Panther's Afrofuturism — and other important works like (Seattle Review of Books contributor) Nisi Shawl's novel Everfair, which decolonializes steampunk — is the optimistic science fiction that Stephenson has been clamoring for. It's been simmering under our noses all this time, but the science fiction mainstream didn't think to look for it.

Afrofuturism is the best kind of science fiction: it's aspirational, it's imaginative, it's optimistic, and it is interested in ideas that resonate with the real world. As I've watched Black moviegoers embrace the idea of Wakanda over the last few weeks, I've seen more than just movie fans gushing over a well-made film. By extoling Wakanda's achievements, they're creating positive change in our world. The Wakanda the Vote program, which registered voters at Black Panther screenings, is perhaps the most obvious sign of its real-world effects. But subtler signs, like actors giving each other the Wakanda forever salute at the Independent Spirit Awards, indicate that the symbol of Wakanda is going to resonate in and interact with everyday life in very interesting ways.

It's easy for longtime (and mostly white) sci-fi fans to lament the so-called golden age of the genre, when the stories were all glossy rocket ships and laser beams and bright-eyed exploration. But the truth is that the good old days were never so good as they seem — a whole lot of people were excluded from that golden age of sci-fi.

Meanwhile, Afrofuturism is new and optimistic and exciting, and it's creating the space to reimagine what the world is, and what our heroes can look like, and how our societies should behave. It's new and it's powering one of the most popular films of all time and it's changing the world. Seems to me that we're right now living in a new golden age.

Picking up the pencil

Published March 07, 2018, at 12:00pm

Artist and illustrator Laura Knetzger tries the famous 12-week course in creativity to see how well it works.

Talking to Couth Buzzard owner Theo Dzielak about the Greenwood bookstore's future

Last week, Greenwood bookstore Couth Buzzard launched a GoFundMe campaign to raise $9,500 in order to keep the store going. Owner Theo Dzielak announced that the store needed the money to address "sharp increases in rent, license fees and taxes, supporting our employees with fair wages, the effects of new health and environmental regulations, the ongoing need to repair and replace aging equipment, and many other costs."

The store is now more than halfway to the goal. I called Dzielak to discuss the campaign and the Buzzard's future. "I'm happy with the way it's going," Dzielak tells me. Even though "it's not the easiest thing to do to ask for money," he admits, "we've been building community for a long time and I knew people would step up."

Finding items to sell for the fundraiser was easy, Dzielak says. "A number of local authors stepped forward and donated copies of their books: Peter Mountford, Nick Licata, and David Shields. I know a lot of local artists and they donated paintings and pottery - they all stepped forward and said 'how can we help?'"

Dzielak notes that sales at the Couth Buzzard increased last year, and continue to climb. The money from the GoFundMe will help the Buzzard invest back into the store to meet the customer demand. For years, Buzzard has carried a mixture of used and new books. Over the last few years, customers have gravitated more toward the new titles, and Dzielak intends to invest in a larger collection of new books to make his stock more relevant. Additionally, the funds will support "bringing new products to the café and support other advertising and increase the slate of events."

Owning a bookstore and community center, Dzielak says, is "an experiment every day." He's proud of the Buzzard's loaded events schedule, which includes book clubs, open mics, musical performances, and readings. This Saturday, the Buzzard is hosting a cabaret tribute to Ursula K. LeGuin featuring Scott Katz, Jeffrey Robert, Lydia Swartz, David Fewster, Matt Price, Arni Adler and Kathleen Tracy. Dzielak is also looking forward to the launch party for Sibyl James's new book Hard Goods & Hot Platters on March 22nd. The wide variety of events, Dzielak says, confirms that the Buzzard is "not just a bookstore. It's a community where art is made."

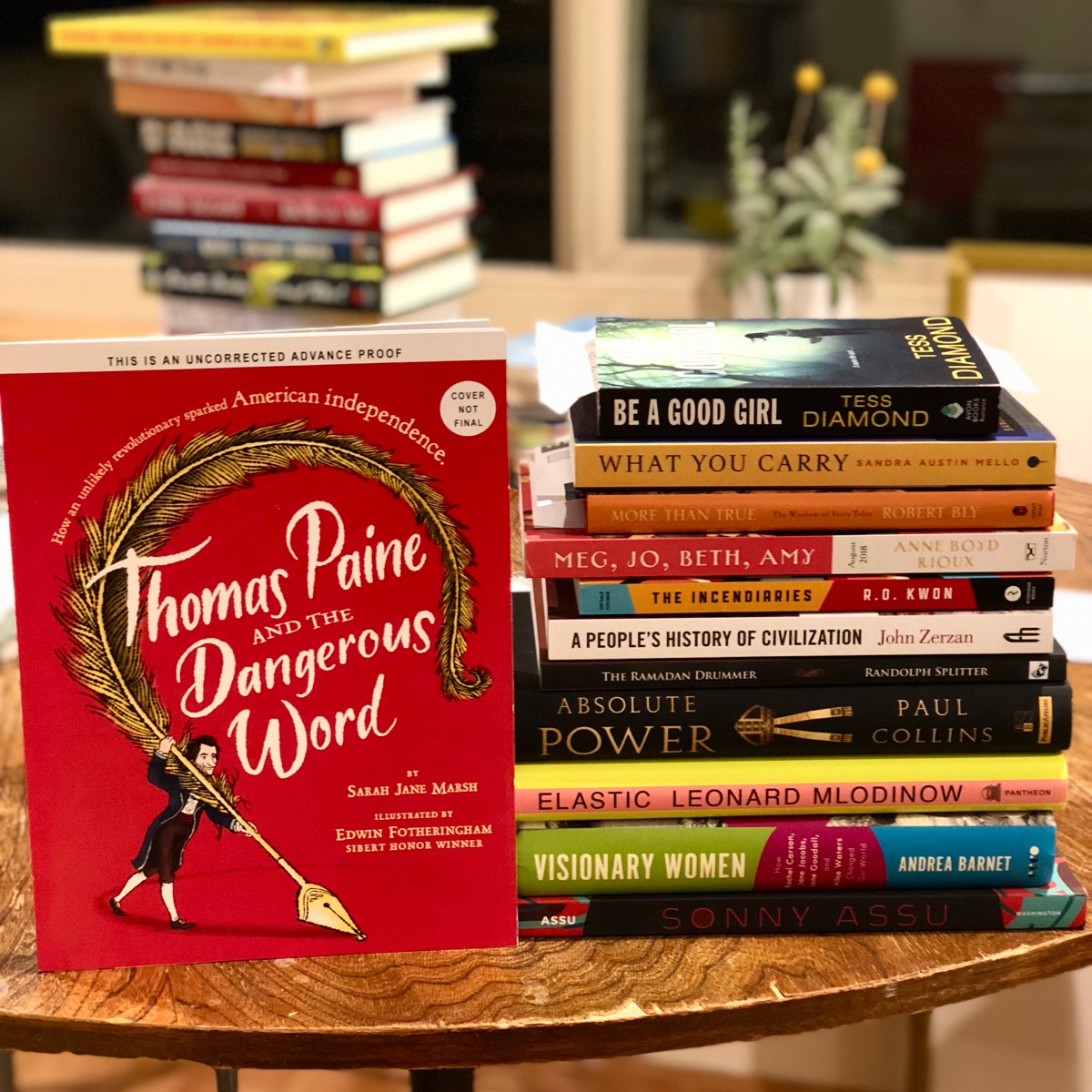

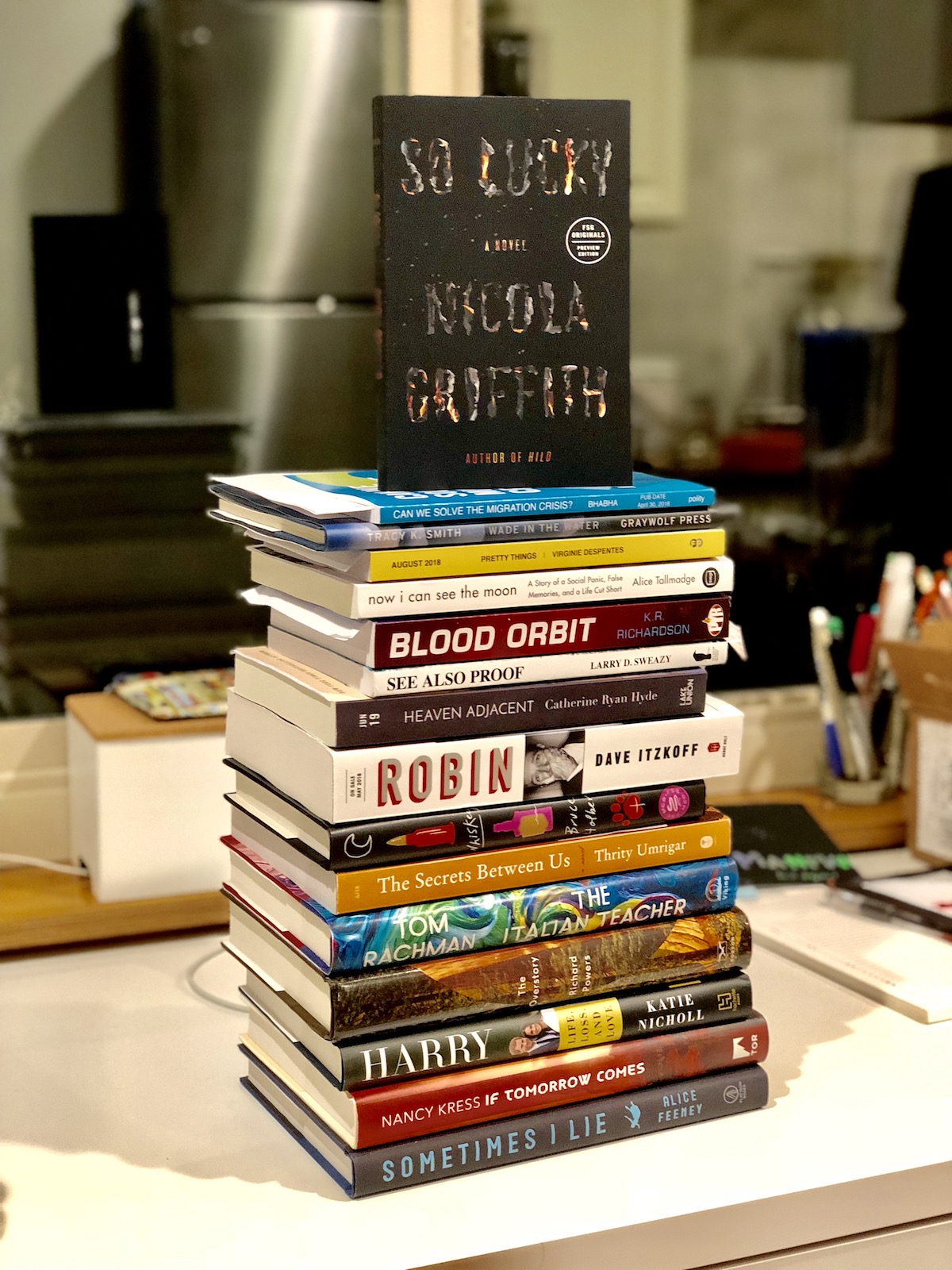

Mail Call for March 6, 2018

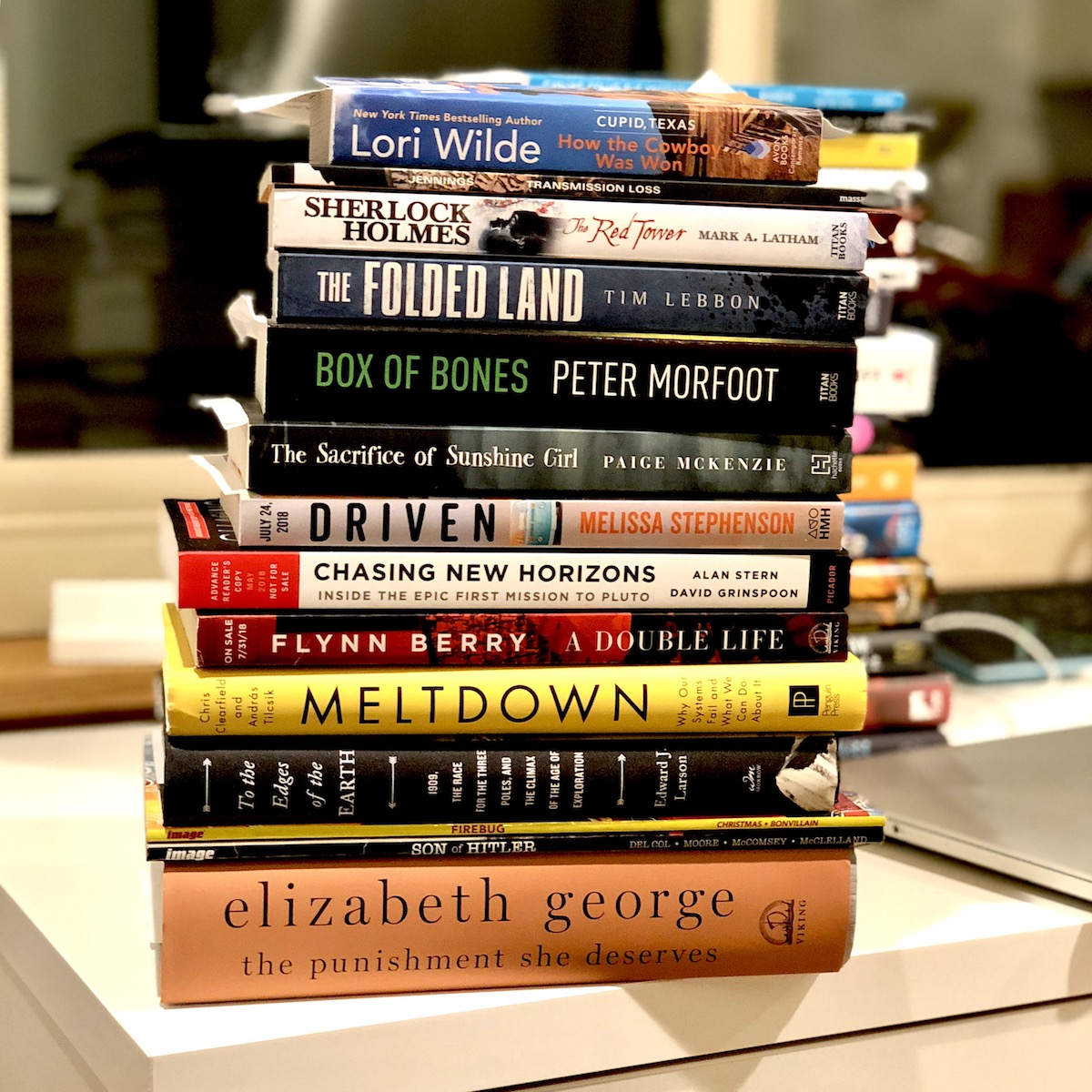

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Land of promise

Published March 06, 2018, at 1:12pm

Natalie Singer's new memoir is "a self-interrogation" that is obsessed with the idea of California. Is it possible to be a pioneer in your own mind?

Finding my way through the troubling Sherman Alexie stories

I believe the women who talked to NPR about being sexually harassed by Sherman Alexie. I admire the bravery that it must have taken to speak up against such a powerful man in the literary community. I hope that sharing their stories helps them find some emotional peace, and if there are others out there who have had the same experience as these women — as we've learned in the last six months, there are often more women — I hope that they find inspiration in the courage that these women displayed.

Before we go any further, let's be clear about some of the arguments that devil's advocates are going to bring up in the wake of NPR's report. You'll likely hear some conversation about due process; that, of course, is not the point. There's no trial, here. Alexie is accused of a breach of ethics, of using his power and prestige to intimidate young authors and coax them into sexual acts. It's up to all of us — as moral beings, as keepers of our own ethical codes — to decide how we interpret and respond to those accusations.

Some people will probably argue that calling for an author to "go away" is just a case of "mob mentality." Nobody is calling for Alexie's books to be burned, or for Alexie to be pilloried in town square. We don't expect our authors to be perfect heroes. But we do expect that when we give them a platform, they will use that platform responsibly. We do expect that when we invite them to our readings, or into our minds, they won't use their fame to take advantage of others.

After seeing these reports — reports which, by the way, follow a statement in which Alexie himself confirms that he has "done things that have harmed other people" — it's up to every reader to decide where they stand on Sherman Alexie's literary works. Some, no doubt, will continue to admire him. Others will feel betrayed. There will be as many different responses as there are readers. This is not a mob. This is a large group of readers — of fans — coming to terms with a new reality.

I don't want to make this about me, because it's not. But I think I have to disclose my connections to Alexie, to continue the conversation started by those brave women on NPR yesterday. For as long as I've been working with books in Seattle, Sherman Alexie has been a part of my life. The week after I started working at Elliott Bay Book Company in 2000, I sold books at an Alexie reading at Town Hall. I'd never seen him read before, and I instantly became a fan. I especially liked how generous he was to the booksellers — how he thanked us for our time.

And once I started writing about books, Alexie became a more prominent and personal figure in my life. I helped select Alexie for a Stranger Genius award. I wrote about almost all of his books. I hosted quite a few readings with Alexie and interviewed him several times. I exchanged many emails with him.

I didn't know any of this about Alexie — but then, I suppose it makes sense that I wouldn't have known. Alexie presented himself to me the same way he presented himself onstage: as a married man who sometimes engaged in harmless puppydog crushes on celebrities and women he might notice in passing on the street. I first learned about the charges against Alexie a month ago, after a bookseller sent an email alerting me to the anonymous allegations. Since that time, I've heard both firsthand and secondhand accounts of women who felt victimized by Alexie. Those accounts sound similar to the stories in the NPR report. I believe them, too.

At first, I was shocked to hear the stories. As I've heard more, as I've talked to reporters and read the stories and accounts, I've felt a growing amount of shame.

It makes me sick to my stomach to think that one of my events or reviews might have been the incident that inspired a young woman to reach out to Alexie, only to be harassed by him. It makes me feel even worse to think that someone might have wanted to tell a member of the media about their experiences with Alexie, but that they might have considered that I would not have believed them because I've been so closely affiliated with him over the years.

And so personally, for me as a reader? Until last month, I believed in the Alexie that presented himself onstage. I loved his willingness to stand up to bullies, to acknowledge human frailty, to speak beautiful truths. But based on what I have heard now, I have no stomach for him or for his work anymore. The distance between the personal story presented in his writing and the stories I've heard is too far. I can't read those words anymore without thinking about all the pain they're printed over.

I'm not unique in this. You, reading this, will have to formulate your own response to this news. We as a community will be coming to terms with the story over the next days and weeks and months and years. Seattle is a strong city with a mighty literary community, and our people are compassionate and intelligent and we take care of our own.

I have hope that we can figure out how to learn from this moment — that we can find ways to protect our friends and neighbors from abuses of power; that we will create a community that includes voices, rather than silences them; that we will listen, and be listened to. I believe that if we work together, we can remember our goal as a literary community: to tell stories that make the world a better, more just, more empathetic place.

Ordinary Essentials

We may have been young and stupid

We tried things this life

We survived to tell or hold our tongueI only wanted good teeth

It was the kind of day that kissed

my adrenals, I was in love but didn’t

know, I forget his essential natureLooking at altars I swim the undersea

Our art, how we breathe it

becomes our moment of forgivenessEverything essential dies or disappears

Fear takes us out of our bodyI waited forever to sing

They wrote a song with ordinary

words about an ordinary man

I could not stand to listenThe whole world cries each day

Let the bells ring

NPR publishes report accusing Sherman Alexie of harassment

Lynn Neary at NPR published a report this afternoon accusing Seattle author Sherman Alexie of sexually harassing female authors. This report is especially noteworthy because it's the first in recent days to actually include the named testimonies of three women.

In the report, Seattle author Jeanine Walker, Erika Wurth, and former Seattle author Elissa Washuta each recalled personal experiences with Alexie. The particulars vary from story to story, but taken in aggregate they paint a portrait of Alexie as someone who abuses his high standing in the literary community to make aggressive sexual advances on emerging women writers.

Neary writes:

In all, ten women spoke to NPR about Alexie — who is a married man. Most of the women wanted to remain anonymous, but a clear pattern emerged: The women reported behavior ranging from inappropriate comments both in private and in public, to flirting that veered suddenly into sexual territory, unwanted sexual advances and consensual sexual relations that ended abruptly. The women said Alexie had traded on his literary celebrity to lure them into uncomfortable sexual situations.

We're continuing to watch as other reporters publish their findings on this situation. We'll have more to say soon.

Look again

We look at the world in a sleepy way, especially through the lens of social media, where images slide past in a blur. Stark's book is like caffeine for the visual center of your brain. Stop by our sponsorship page for a glimpse at the rich images she's captured while traveling the world, and her take on them. Then go for a long walk. Keep your eyes open. See what you see.

Sponsors like Lois Farfel Stark make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? If you have a book, event, or opportunity you’d like to get in front of our readers, reserve your dates now.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from March 5th - March 11th

Monday, March 5: California Calling Reading

Natalie Singer was from Canada. She dreamed of living in California - wrote a whole book about it, in fact, titled California Calling - and now she's living in Seattle. Tonight, she debuts her lyric memoir with another Seattle author, Sonora Jha. This book is getting a lot of pre-publication praise and it's from great Oregon publisher Hawthorne Books and this reading is free, so you have no excuse to skip this one.Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Tuesday, March 6: If Tomorrow Comes Reading

Seattle sci-fi author Nancy Kress's latest book, If Tomorrow Comes, is about humanity building a spaceship called Friendship. We head to the stars to try to find aliens who once visited Earth and then disappeared. What we find instead is a total mystery. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, March 7: So You Want to Talk About Race Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, March 8: Love and Other Consolation Prizes Reading

Seattle author Jamie Ford wrote Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet, a historical novel about a hotel in Seattle's International District. His newest novel, Love and Other Consolation Prizes, is set in the Seattle of 110 years ago and it's based on a true story. Carco Theatre, 1717 SE Maple Valley Hwy, Renton, 775-8600, 7 pm, free.Friday, March 9: The Monk Woman's Daughter Reading

This novel by a Seattle-area author takes place in the middle of the nineteenth century. It contains slavery, addiction, romance, and adventure. It's also got a pretty good first line: "My mother said she was a nun. That may have been a lie." Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.

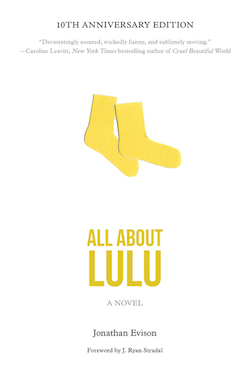

Saturday, March 10: All About Lulu Reading

About a decade ago, Bainbridge Island author Jonathan Evison published his very good debut novel, All About Lulu. Tonight, he's celebrating a special 10th anniversary edition of Lulu with a big party including music from Mary Ocher and probably some cheap beer. Evison is publishing a new novel, Lawn Boy, later this year, so this event will likely be a ramp-up as the author transitions from the monklike world of writing to a more public-facing world of book tours.. Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery, 925 E. Pike St., 658-0110, http://fantagraphics.com/flog/bookstore, 6 pm, free.Sunday, March 11: Don't Skip Out on Me Reading

Singer/songwriter Willy Vlautin is a local favorite who comes to town to charm audiences whenever he publishes a new novel. Press materials indicate that in Vlautin's latest novel, "Horace, a Paiute and Irish ranch hand, decides to become a boxer." Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.Event of the Week: So You Want to Talk About Race at Elliott Bay Book Company

Ijeoma Oluo didn't ask to be Seattle's conscience. But often the most responsible, honest person in any given area is granted a role of community conscience - especially if they'd never asked for that role in the first place.

At times, it seems as though Oluo is biologically incapable of writing a dishonest word. She speaks the truth, clearly and repeatedly. She doesn't suffer fools. She speaks against injustice as often as she needs to, and the world is a very unjust place.

If that hackneyed old quantum theory of infinite universes is true, there's a universe somewhere out there in which Oluo doesn't have to work as a 24-hour truth-teller. In that universe, she films makeup tutorials on YouTube and she writes hilarious reviews and humorous personal essays.

But we live in a universe where everything feels wrong - where systematic racism and sexism has been normalized to the point that demanding equality is enough to mark you in the eyes of the mainstream as a crybaby or a reactionary. And because this is our universe, Ijeoma Oluo wrote her first book, So You Want to Talk About Race. (Oluo reads from the book at Elliott Bay Book Company this Wednesday.)

"Race is not something people can choose to ignore anymore," Oluo writes toward the beginning of Race. For too long in this country - and in Seattle - we've ignored race. White people have pretended that the "problem" has been "solved," that we're in a liberal utopia where race doesn't matter. But thanks to the megaphone of social media, we've learned that we haven't "solved" anything - we've just kept entire populations out of the conversation.

Oluo, to her credit, refuses to be dour, or lament her thankless role as someone who starts the uncomfortable conversations about race in the media. "I am so glad you are here," she tells the reader at the end of the first chapter of Race. "I am so glad that you are willing to talk about race. I'm honored to be a part of this conversation with you." It's a statement of genuine warmth, a generous welcome.

Race is a step-by-step guide to discussing race in America. It defines every term, and it starts on the ground floor. There's plenty of good, practical advice: if your conversation about race starts to go wrong, for example, and "If you are white," Oluo says, "watch how many times you say 'I' and 'me.'"

The book is conversational and Oluo is a disarming host. Rather than open her conversation of privilege with a host of bad examples, for instance, Oluo dissects all the privilege in her life that has led to her publishing her first book. The word that comes to mind, again, is "generous."

By the time Oluo has moved into the most controversial topics of our time - police brutality, cultural appropriation, so-called "callout culture" - she has disarmed all but the most hateful readers. Race is exactly what she promised the book to be - a conversation, one that draws in a reader and engages their ideas with a thorough and loving series of questions.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for March 4, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

How to write a memoir while grieving

When Nicole Chung’s father died, she was still writing the story of her family and her adoption — the memoir was due to her editor just one day after she found out he was dead. Here she explores how both the book and the loss of her father pulled at the threads of their family, loosening some and tightening others. There’s something sinuously meta about this piece; she’s writing a story about writing a story that’s taking place while she’s, um, writing it. And also something remarkable about the gentleness and honesty with which she navigates that looping narrative.

Someone recently asked me how my dad’s funeral went, and I said, “It was beautiful. My mother was really happy with how it went. And my sister was there with me, which was so kind of her.” The person nodded, looking a little confused. Isn’t that obvious? their expression seemed to say. Of course your sister was there. “Oh,” I said, “no. She didn’t have to be there. We don’t have the same dad. Ah, but we do have the same parents.” They just kept looking at me, like, Sorry, you’ll have to give me a bit more.

Sliced & Diced

It’s not easy to make statistical method scandalous, but Stephanie E. Lee achieves it with her story about Brian Wansink. Wansink is a rockstar of social science (if such a thing exists), head of the prestigious Food and Brand Lab at Cornell University. He’s published dozens, if not hundreds, of studies in peer-reviewed journals, many of them headline-worthy. Turns out it’s not that hard to do newsworthy science, if you start with the headline and trim the data until they fit.

In 2012, Wansink, Payne, and Just published one of their most famous studies, which revealed an easy way of nudging kids into healthy eating choices. By decorating apples with stickers of Elmo from Sesame Street, they claimed, elementary school students could be swayed to pick the fruit over cookies at lunchtime. But back in September 2008, when Payne was looking over the data soon after it had been collected, he found no strong apples-and-Elmo link — at least not yet. “I have attached some initial results of the kid study to this message for your report,” Payne wrote to his collaborators. “Do not despair. It looks like stickers on fruit may work (with a bit more wizardry).”

Covert cooking: how to bake a pie in prison

Take May Eaton’s piece on baking behind bars with a grain of salt (no pun intended); in the prison experience she describes, contraband means stolen meats and bartered bananas. A missing stapler isn’t stolen for use as a weapon, just mis- or mischievously placed in a waste bin. Prisoners fabricate Faberge-like eggs as gifts.

That’s not to invalidate what she has to say about the persistence of the need to make, to create, even when freedom is limited in the most severe ways; her essay is both interesting and inspiring. But after you read Eaton, balance it out with Jerry Metcalfe’s first-person account of the life prison normalizes for most people held inside.

I still didn’t understand how a handful of ingredients could be turned into a pie that looked and tasted almost as good as one you’d find on the other side of the fence. The prisoner tapped his nose, reluctant to divulge a trade secret, before ego got the better of him. First, he explained, he had stripped the insulating cable on his hi-fi, using the exposed wire to “defibrillate” a can floating in a tub of water, instantly transforming condensed milk into dulce de leche. Pour the caramel over some crushed biscuits and top with mashed banana and you had banoffee pie.

Whatcha Reading, Rufi Thorpe?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Rufi Thorpe is the author of the novels The Girls From Corona Del Mar, and most recently, Dear Fang, With Love (which I unabashedly gushed over). She lives in Calfiornia, and aren't we curious what this is gonna be about?

What are you reading now?

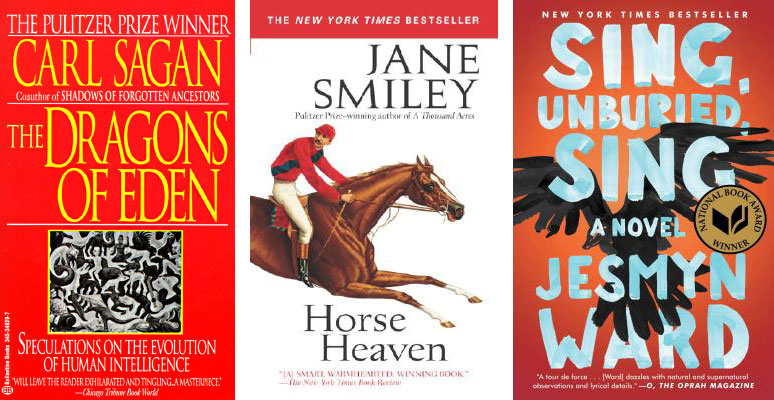

I realize this is peak nerd, but I’m reading Carl Sagan’s The Dragons of Eden, which is about the evolution of human intelligence. Sagan is trying to synthesize anthropological evidence, evolutionary biology, psychology and computer science to paint a portrait of how our intelligence and consciousness arose. I’m always a sucker for the hard-problem of consciousness, and I think when I was younger I was more interested in mystical or abstract/philosophical explorations of those central questions. But after having children, our animal nature has just never been clearer to me, and so I have had to consider human beings all over again in a new light. Sagan is accessible and funny, but the ideas are complicated and fascinating, the kind that make you gasp in the bathtub and close the book because you are dizzy with tracing the ramifications.

What did you read last?

Horse Heaven by Jane Smiley. I made a commitment to myself for 2017 to read the entirety of both Jane Smiley and Margaret Atwood, which is really the ultimate form of self care because neither of them can write a book that is less than brilliant. I’ve mostly been listening to the audiobook versions. I do a lot of reading for my professional life — to blurb or review or just keep up, but I tend to choose audiobooks for my pleasure reading, and then I listen as I do dishes, fold laundry, walk dogs, drive. I love audiobooks too because they read slower than I would read the text visually, so I have room to think a lot about what the writer is doing and why and how. With Horse Heaven, which is a massive multi-threaded novel set in the world of horse racing, I fell in love in a way I’m not sure I have since I was eight and first reading Anne of Green Gables. You know that feeling of just never, ever, ever wanting the book to end? That you would willingly trade your own consciousness and life in order to exist solely in the matrix of the fictive world? That is how I felt about Horse Heaven. And I don’t even like horses!

What are you reading next?

Well, Sing, Unburied, Sing, by Jesmyn Ward is definitely on my list. I’m always extremely interested in books about prison or people getting out of prison. Prison seems to me to be the sort of elephant in the room of modern life. The US has about two million people incarcerated in either prison or jail, 1 in every 37 adults is under some form of correctional supervision. We have no coherent social position in terms of why we are doing this. No one is clear on whether incarceration is meant as punishment or rehabilitation, and meanwhile we have overwhelming evidence that spending time in prison does nothing but further criminalize people and make it less likely for them to find gainful employment and build a happy, functional life. And yet, in a single year we can spend $81 billion on corrections. We invest so much of our energy and our resources as a nation into a system that apparently does nothing positive at all. It’s so irrational that you know it is at the very heart of everything that is wrong.

Mail Call for March 2, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

The Help Desk: How do I put down the phone and pick up the book?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

My willpower seems to be diminished to the point of nothingness. I can’t stay off my phone long enough to read a damn book. When I’m reading, my phone pings and I check it and then I start reading about politics and then it’s two hours later and my book is sitting there unread. I miss reading! Any idea how to help me stop staring at my phone all the time?

Shanna, South Park

Dear Shanna,

"Willpower" is one of the rare and beautiful words in the English language that embeds the seeds of its success into itself, much like "auto-erotic asphyxiation." But when it comes to the internet, we all have chains that bind us. Mine is routinely checking local and state inmate rosters and corrections databases for people I know, a charming tic inspired by my biological father, who before his death managed to rack up five DUIs without my knowledge.

When I need a break from my own neuroses, I like to pick out a book and invite a human friend to coffee. I buy her a drink of her choosing and then ask about life, love, and her plans for the day. I listen to her talk about her cat issues and work issues, I smile and frown when appropriate. While she is distracted by my human empathy and generosity, I slip my phone into her purse. When she leaves, I am free to enjoy several hours of uninterrupted reading or writing in my favorite coffee shop.

Eventually, I must hunt her down and confront her about the phone. If she insists that no, she does not have my phone, I will gently bring up her 2014 arrest for petty theft. She will be horrified – moreso when she discovers the phone in her purse. I have introduced self-doubt into her mind, another uniquely human emotion. If she is a decent friend, she will offer to buy me dinner to make up for my trouble.

This delicate dance cannot often be repeated – eventually, your friends will catch on and learn to buy purses that zip. However, nearly limitless variations exist – leaving your phone in others people's cars or homes, for example. The key is not to flex your willpower but to separate yourself from the very thing that cripples it, freeing your mind to turn to truly healthy and pleasurable things, like the immersive world of a good book.

Kisses,

Cienna