Thursday Comics Hangover: Passing in the night

Berger Books, the new editor-driven imprint from Portland publisher Dark Horse Comics, is something new in the world of comics. It's a bet that readers of comics actually care about editors - or even really understand what comics editors do, for that matter. But to be fair, Karen Berger is one of the most successful editors in comics history: she created DC Comics's wildly successful Vertigo line, which created the template for modern mature-readers comics.

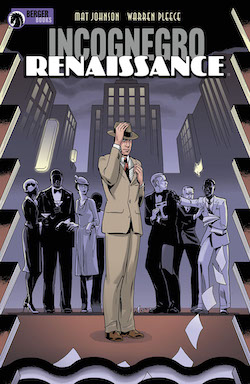

And now that Vertigo has largely disappeared, maybe there's an underserved audience that will flock to Berger Books. I certainly hope so; based on the one book from Berger that I've read - writer Mat Johnson and artist Warren Pleece's Incognegro: Renaissance, the first issue of which published just last week - this is a line that's deserving of a very large audience.

Renaissance opens with our hero, Zane Pinchback, attending an un-segregated party in honor of a new novel about Harlem written by a white author. The publisher praises the author for "braving streets of Harlem rarely seen by white eyes," which causes all the Black eyes in the house to roll violently back in their skulls. ("Another hand for the great white warrior, back from safari," one Black partygoer blurts as he chugs on a bottle of wine.)

Johnson and Pleece elegantly set the stage here: they walk us through the party, introduce us to all the suspects, and then establish a splashy murder of a surprising victim before the book hits page 20. The tensions are high, and everyone's got a motive. Pinchback makes a great detective, as he can code himself on either side of the racial tensions surrounding the murder. I can't tell you how the book will play out, obviously, but Renaissance's first issue is a compelling beginning, and Berger's imprimatur should earn a reader's trust that the story will keep the promise made by the opening chapter.

Book News Roundup: Tacoma park honoring Frank Herbert to open this year

We first told you about this seven months ago, and now it's officially a reality: Tacoma has named a new park after the life and works of sci-fi author Frank Herbert. "Dune Peninsula at Point Defiance Park" is an 11-acre park featuring "Frank Herbert Trail." Tacoma Metro Parks commissioner Erik Hanberg told the News Tribune that Herbert's “experiences in Tacoma shaped his appreciation for the delicate balance of nature, so it feels right to attach his name to a park that reclaims toxic land.” The park is set to open by late summer or fall. We'll let you know when it opens, and we'll take a field trip down to check it out.

Susan Fried at the South Seattle Emerald writes about how the Somali community in south Seattle got together with Seattle Public Libraries, Seattle Public Schools, and the Seattle Housing Authority to create a children's book that celebrates Somali culture and language. The book will soon be available in libraries and schools around the nation.

A stronger man than I would be able to resist the urge to refer to this post as "Poetry in Motion:"

Special thanks to @SeattleArts and @4Culture for allowing #SeattleStreetcar to host this year's #PoetryonBuses for the #LunarNewYearFestival. Check out some of the action, celebrating this year's theme "Your Body of Water"! pic.twitter.com/oyJdkcPyT1

— Seattle Streetcar (@TheStreetcar) February 13, 2018

- Congratulations to Seattle kid's book author Jessixa Bagley, who won a New Writer Honor from the 2018 Ezra Jack Keats Book Award for her book Laundry Day. If you'd like to congratulate her in person, Bagley will be signing her latest book at Secret Garden Books in Ballard this Sunday, February 18th at 4 pm.

In a virtual world, trolls are real

Published February 14, 2018, at 12:16pm

After Gamergate — correction, a petty, dangerous ex-boyfriend — unbuilt her life, Zoë Quinn used her game-designer smarts to turn the tables on online harassers. It's time for the rest of us to do the same.

No writer stands alone: a conversation about community with Rita Wirkala and Jeffrey Cheatham

A little over a week ago, I moderated a panel on DIY culture for Literary Career Day at the Seattle Public Library downtown. The panel conversation was between myself, author Jeffrey Cheatham of the Seattle Urban Book Expo, and poet Rita Wirkala of Seattle Escribe, but many of the dozens of young aspiring authors in the room took part in the conversation, which covered a wide array of topics.

Cheatham talked about his surprising success with the first Urban Book Expo, and his current attempts to turn the festival into "an actual movement, a culture" that represents writers and readers of color in Seattle. Wirkala discussed her history as a writer and a publisher and a published poet, as well as her work with Escribe, which she describes as an organization featuring readings, "classes, and workshops for people who are writing" in the Seattle area.

Most of the questions centered around how they manged to build a community, and how they kept the community going once it got started. Wirkala said "I'm not very good at finding people, but people have found me" because she kept herself available as a publisher and a writer. Putting her name out and maintaining a presence in the city meant that like-minded could easily find her. As to maintaining the community, she attributes that to the "self-generated energy" created when "you find people who are on the same wavelength and you fit with them."

Cheatham said when he created the first Expo, he went on a listening tour. "I listened to potential clients, because they'll tell you what you're looking for when they go to events," and then he took it upon himself to "mold the show to fit what they wanted." And in order to more than double the size of the second Expo, he says he kept his ears open after the first one. "I just listened to my customers. They told me what they wanted."

Putting on an event is hard work, Cheatham notes, but if you listen and create a space, people "as human beings want to find something they can call their own and work together on." Everyone's looking for their people, and they're willing to work to keep their community together.

Those groups are important for writers and publishers, Wirkala agreed, because "when you write, or when you're engaging with work, you are too close to it as an idea. You always need somebody to help you" gain some distance from the work. "And you learn a lot from other people who are in the same field. That's really important," she added.

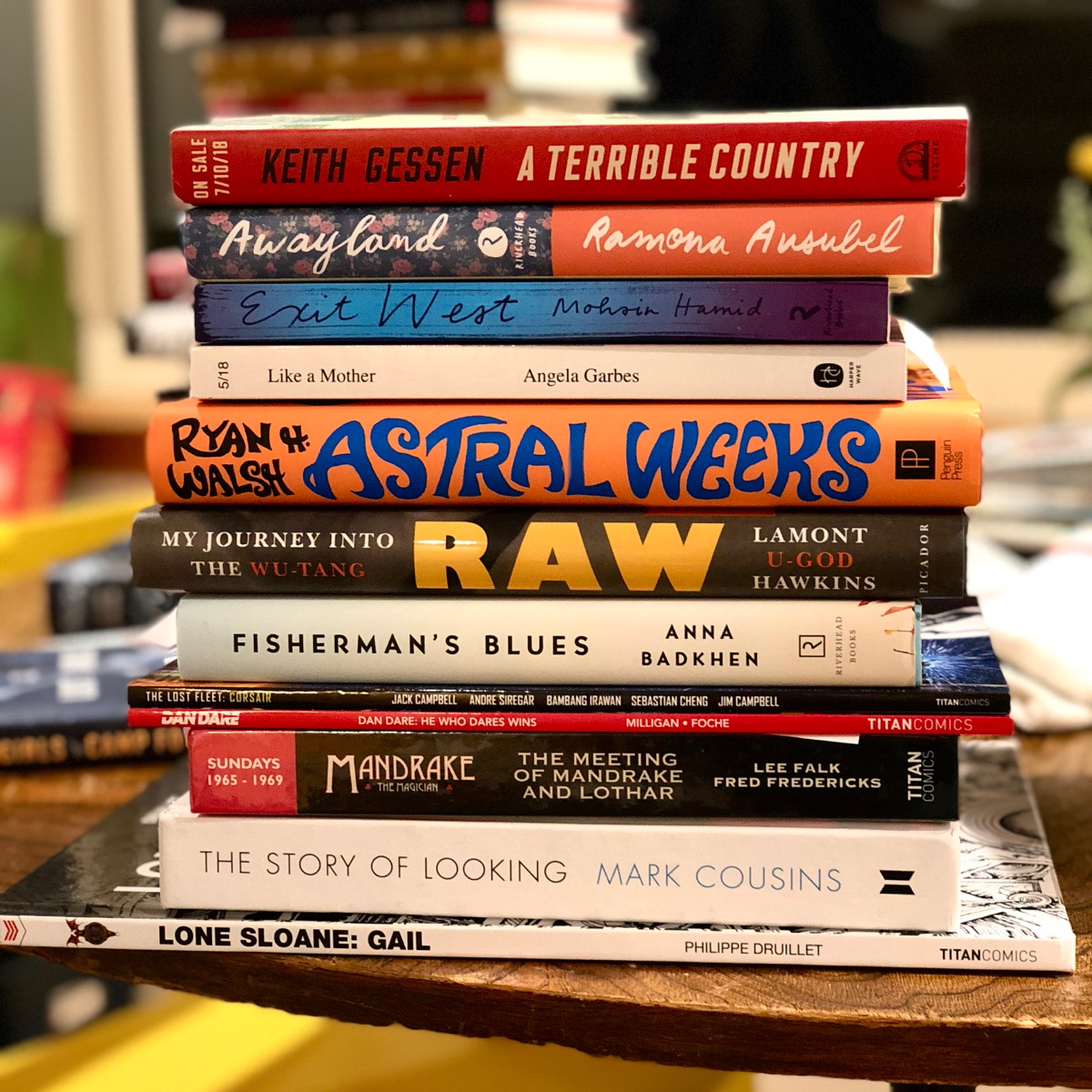

Mail Call for February 13, 2018

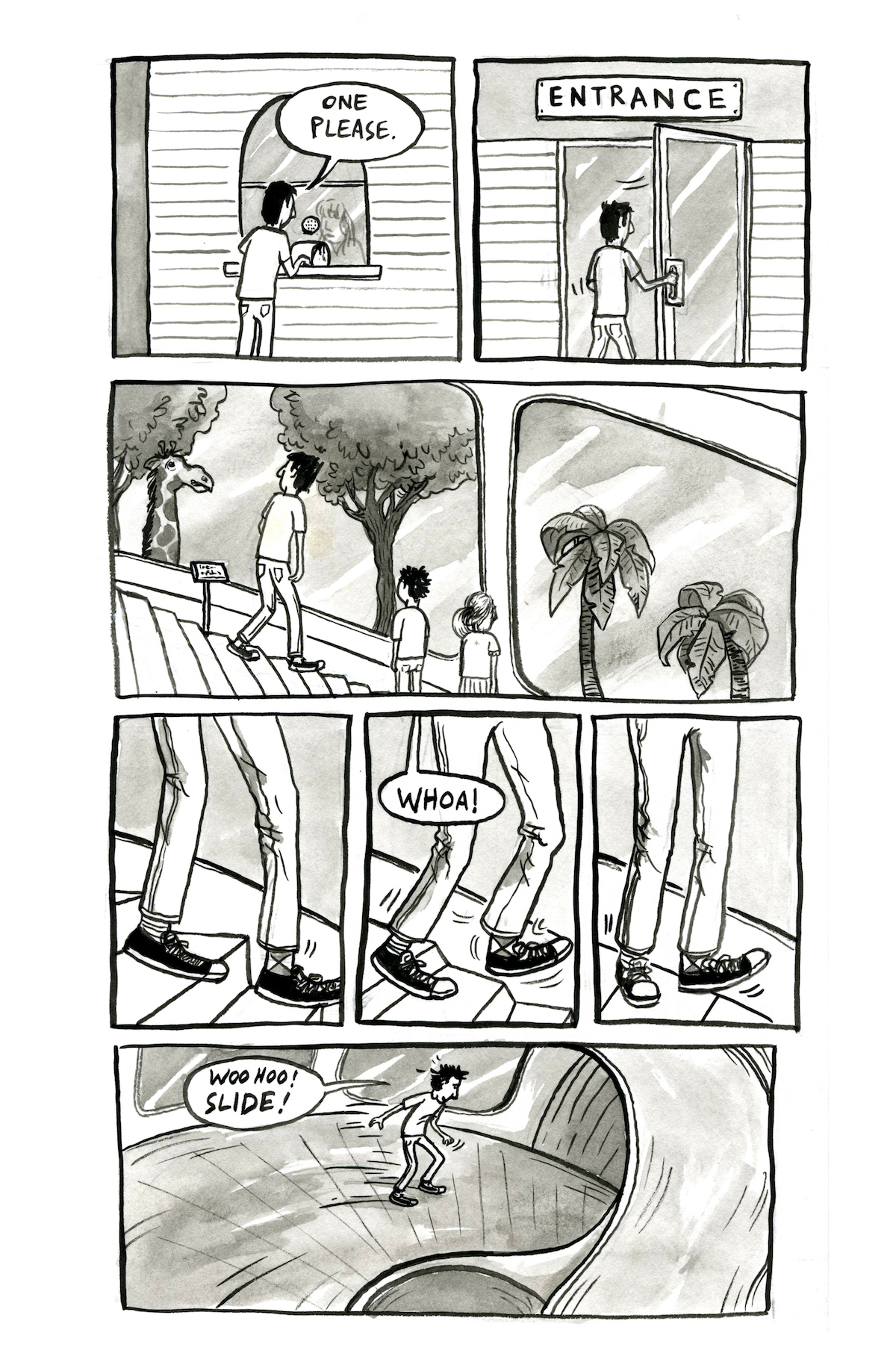

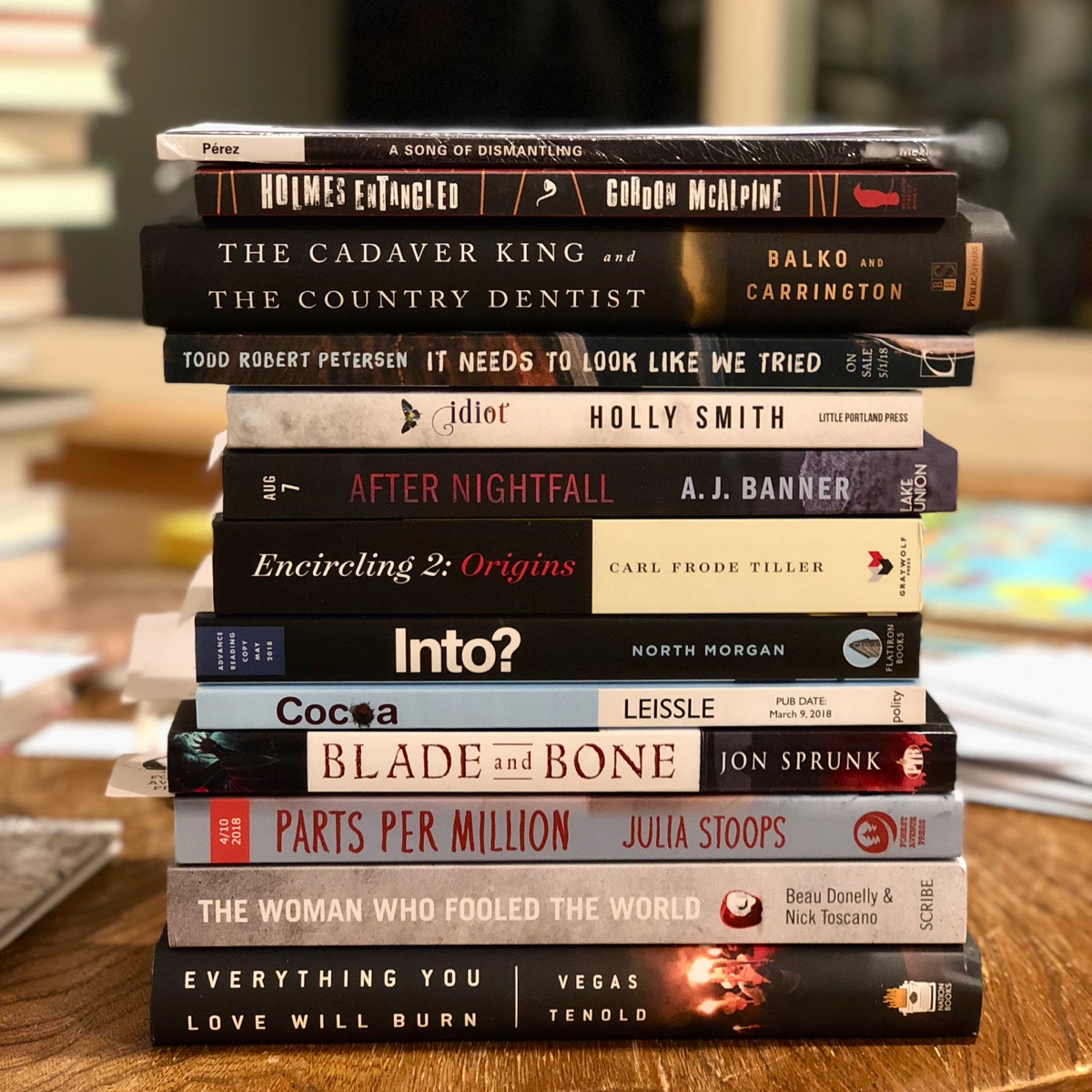

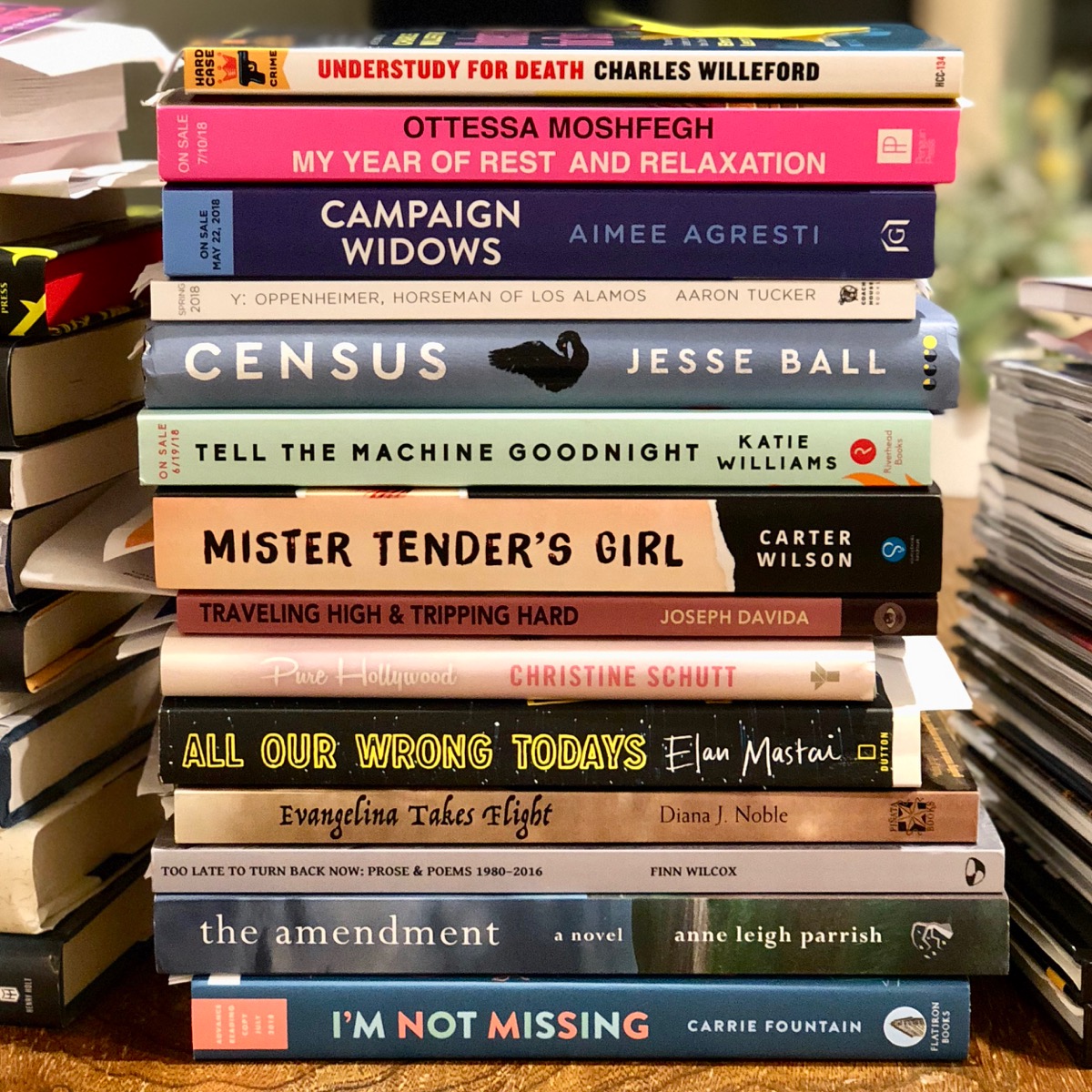

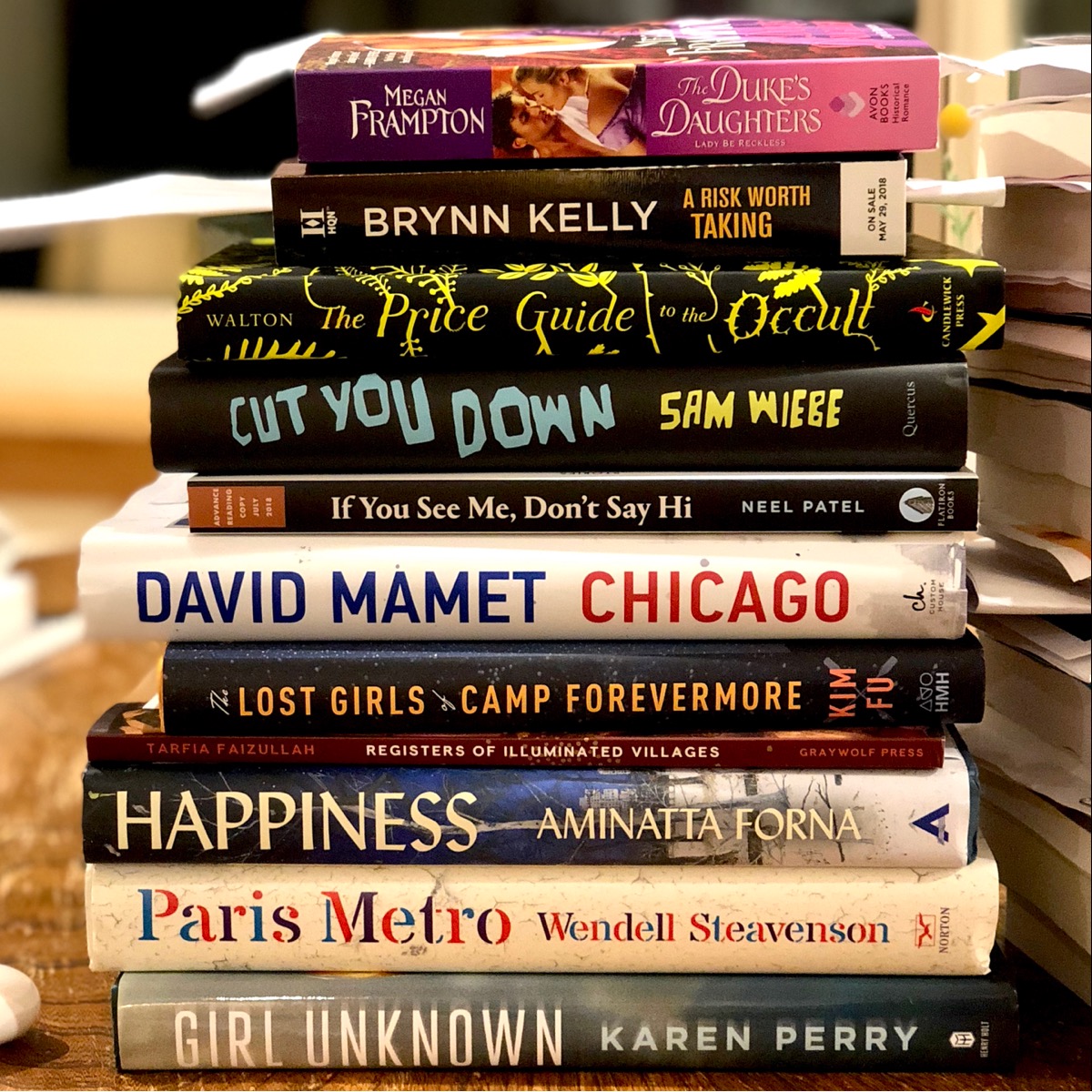

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Barnes & Noble laying off staff

After a terrible holiday season, Lauren Thomas and Lauren Hirsch report for CNBC, Barnes & Noble without warning laid off an unspecified number of employees on Monday morning.

Barnes & Noble is trimming its staff, laying off lead cashiers, digital leads and other experienced workers in a company-wide clearing, CNBC has learned from sources familiar with the matter...The number of affected workers couldn't immediately be determined. As of April 29 of last year, Barnes & Noble employed about 26,000 people.

The smart thing for Barnes & Noble to do would be to give its employees more control over its stock, to make each store a unique neighborhood hub with plenty of local character, and to create welcoming spaces staffed by well-read employees. Of course, the company will likely do the exact opposite: more corporate control over stores, cost-cutting measures that make the stores feel even more empty, and fewer staff around to make personalized recommendations and to create local flavor.

I worked at Borders as it started its slow, sad corporate decline — you can read my account of that here — and from the outside, this Barnes & Noble news looks very familiar to me. There's always some possibility that Barnes & Noble might be saved, but I wouldn't bet money on it.

It's time for the publishing industry to start figuring out how to thrive without a Barnes & Noble in every corner of the nation. Right now, losing B&N would be disastrous for publishing and for American literature in general; it would move all the power to Amazon, and it would close the only bookstore in many rural communities around the country. If I were one of the big publishers, I would start organizing with independent bookstores — right now — to figure out a way forward together.

Be prepared

Published February 13, 2018, at 11:56am

Tonight, Seattle author Kim Fu reads at Elliott Bay Book Company. Her new novel, about a group of girls at summer camp who get lost and must fend for themselves, is a remarkable book that adds something new to the lost-in-the-wilderness genre.

Healing in Golden Repair

forget your perfect offering

just ring the bells that still can ring

there is a crack in everything

that’s how the light gets in

- Leonard Cohenthere is a crack in everything

my professor shows us kintsukuroi tea cups on the projector the Japanese to English translation means

“golden repair”

she says

traditionally, the same tea cups are used in ceremonies for generations, their cracks filled in with gold.

it’s the damage that makes them beautifulthat’s how the light gets in

i am glass half empty

my heart is the size of my fist too often i give myself beatings

potential

leaking through cracks i makei say, “my idealized self would have fixed these by now” wouldn’t have made cracks in the first place

her, some kind of invincible spiritual plumber

heals as a pastime & is never late

her confidence doesn’t have an asterix at the end all her cracks

are endearing

and forgivableshe gets a red ribbon cutting when they’re fixed within a

two day weekend.

meanwhile, no one throws a ceremony when i manage to get out of beddo cracks even deserve gold when they take this long to fix?

i imagine liquid motivation spilling on bedroom floor, bus seat, hallways

all the countless hours wasted trying to find the newest, quickest method of being alonewhen my wounds heal and shut into thicker skin i dig into my heart’s topsoil

— cracked & barren —

for feeling

try to rip this numbness out like a bad root

try to hold onto

feeling

like scarce nuggets of gold never seem to be worth enoughso i let my wounds be tender, golden & feeling instead

it’s own type of healing insteadmy mother writes

“if light could speak,

It would say your name”forget your perfect offering

the Latin to English translation of the word

patience

means “quality of suffering”there will never be a time when i’m untouched by hardship

this world don’t have much patience for self care that interrupts the work week yet here i am

reclaiming my time

forgiving myself for all i’ve let slip

I stop missing my idealized self because i will never meet her

i call recovery

“healing” instead

because i know how it feels in my handsbecause i don’t look for it in a mirror

just trust how it beats in my chest,

never as fast as i want,

but patiently doing the work nonethelessjust ring the bells that still can ring

i throw a small ceremony when i get out of bed

I decide, that’s its own kind of beautiful ritual of patience

the kind able to be used for centuries

The flimflam man is back, again (with a new chapter for you)

Sponsors like Pope Brock make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? If you have a book, event, or opportunity you’d like to get in front of our readers, reserve your dates now — June and July are the last dates available in our first block of the year!

Congratulations are due to Seattle author Sherman Alexie, who won a Carnegie Medal for his amazing memoir, You Don't Have to Say You Love Me. Love Me is the non-fiction winner, and Jennifer Egan's acclaimed Manhattan Beach won the fiction prize this year. If you haven't read either of these books, you should fix that right away.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from February 12th - 18th

Monday, February 12: African-American Writers' Alliance

Seattle writing collective The African-American Writers' Alliance shares their work in one of their regularly scheduled south Seattle events. Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, February 13: Guts Launch Party

Janet Buttenweiser, a Seattle writer and teaching instructor, launches her memoir into the world. Guts is an account of her ongoing battle with Crohn’s Disease, which includes “three surgeries, two months without eating, eight months of ileostomy, and five hospital stays.” Sorrento Hotel, 900 Madison St., 622-6400, http://hotelsorrento.com, 7 pm, free, 21+.

Wednesday, February 14: Winterfolk Reading

Winterfolk is a young adult novel about a teenager “who has lived with her father in Seattle’s infamous homeless encampment for five years.” After sweeps of the encampment begin, she winds up fleeing into Seattle, which is not a welcoming city for folks like her. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, February 15 I Gave This Dream to a Color Reading

C. C. Hannett is a pen name for a local poet. His latest book, published by the excellent Spuyten Duyvil press, is titled I Gave This Dream To A Color. His next book, Triune, will be published this summer. He’ll be joined by local writers Amber Nelson, Bryan Edenfield and Julianna Buckmiller. Couth Buzzard Books, 8310 Greenwood Ave N., http://buonobuzzard.com, free, 7:30 pm.Friday, February 16: Bushwick Book Club

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, 104 17th Ave S, 7:30 pm, $10.Saturday, February 17: Racism, Vulgar and Polite Reading

Racism, Vulgar and Polite: The Discriminatory Inclusion of Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during WWII tells the story of racism in the time of war. World War II created a tectonic change in the way people of Japanese and Korean descent were treated by those around them. Pigott Auditorium, Seattle University Campus Walk, 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org, 6 pm, $5.Sunday, February 18: Fran Lebowitz

I’ll be interviewing Fran Lebowitz, one of the most brilliant wits of our time, onstage at Benaroya Hall. No pressure or anything. Benaroya Hall, 200 University St., 215-4747, http://seattlesymphony.org, 7 pm, $50.Literary Event of the Week: Bushwick Book Club at Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center

At this point, you likely know the deal with the Seattle branch of the Bushwick Book Club, right? They’ve been around for years, so odds are good you’ve encountered at least a listing for one of their events. If you’re new here, or if you haven’t been paying attention, here’s the deal: local musicians create all-new music in response to a book. The results obviously vary, depending on the book and the musicians who are participating. That’s how anthologies work!

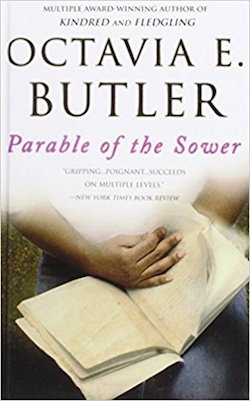

But this week, we’re about to bear witness to the closest thing the Bushwick Book Club has ever seen to a Sure Thing — a guaranteed fantastic time. This Friday, February 16th, at the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, the Bushwick Book Club will create new music based around Seattle sci-fi giant Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower.

Butler, of course, is one of the greats — the first sci-fi writer ever to win a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, and arguably the sci-fi writer who did the most in the 20th century to legitimize the genre as an art form. Sower predated the dystopian fiction craze by a half-century, and its story—about a young woman who is gifted (or cursed) with a supernatural empathy—pretty much instantly became a science fiction classic.

The Book Club called in KEXP’s DJ Riz (Riz Rollins) as a guest curator, and he’s selected an all-star lineup of Seattle talent to participate: Om Johari, JR Rhodes, Coreena Brown, Reggie Garrett, Tiffany Wilson, Adra Boo, Okanomodé, Nikkitta Oliver, Monique Franklin and Yonnas Getahun.

So we’ve got a world-class writer, one of Seattle’s very best DJs as curator, and a revitalized arts organization to host. Could this be the very best Bushwick Book Club ever? All signs point to yes.

Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, 104 17th Ave S, 7:30 pm, $10.

The Sunday Post for February 11, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

My Own Alternate Universe

Kristen Peterson’s piece on working at a convenience store in Las Vegas is a rare example of the “I took a low-paid job” essay that’s thoughtful and respectful — the viewpoint of a resident of the job, not a tourist.

Gas stations are convenience stores, a title that’s taken literally by customers who need to be somewhere else five minutes ago. Every emotion is on display here. They’re vulnerable, captive to our abilities, bound to expectations that don’t always play out as smoothly as expected. All you do is ask a customer to reswipe their card and you’d think from their expression that you just told them their best friend has drained their bank account. Bewilderment and anger collide in their minds as they stare at you.

I Spent Two Years Trying to Fix the Gender Imbalance in My Stories

My favorite phrase from Ed Yong’s detailed account of his two-year project to balance representation of men and women among the sources for his reporting? “Anyone can do this.” If you’re looking for a how-to, this is a great place to start — and excellent debunking of the standard-issue reasons not to.

We don’t contact the usual suspects because we’ve made some objective assessment of their worth, but because they were the easiest people to contact. We knew their names. They topped a Google search. Other journalists had contacted them. They had reputations, but they accrued those reputations in a world where women are systematically disadvantaged compared to men.

Maybe There’s Nothing Natural About Motherhood

It must be exhausting, supporting a collapsing ideological industry put in place to protect your power and privilege on the basis of what other people do with their bodies. I so very much hope it is exhausting, and worse. Here’s the fabulous Leni Zumas on the politics of conception and who really has skin in the game.

In the first draft of this essay, I described Denfeld as “the mom of three adopted kids.” The word “adopted” here may seem neutral — purely descriptive — but is it? The fact of their being adopted follows soon enough. I deleted it from the introductory line because, once I thought about it, it seemed to reinforce a pecking order in which one’s biological children are standard and need no explanation.

Historically, who has benefited most from appeals to what is “natural,” “normal,” “as God intended”?

White people. Abled people. Rich people. Cishet men.

How Not to Die in America

Molly Osberg inhaled the wrong kind of bacteria and watched her world fall apart — “watched,” in this case, meaning “lived through in an nightmare blur of medically induced coma, emergency surgery, and negotiations with the health care system about whether she was too expensive to save.” Read it, then read the short piece she published a week after the original ran, with stories from people across the country of the hopelessness of America’s health care system.

Sherry Glied, the dean of New York University’s school of public service, put it a little more bluntly: Under even the lowest Affordable Care Act tier, she says, I’d be paying the out-of-pocket maximum — a little over $6,000 — and perhaps I’d be limited to in-network doctors. (The hospital I visited has maintained a relationship with an Affordable Care Act-affiliated insurance provider since 2014.) But depending on an individual hospital’s policy, and my credit score, and where I happened to land, whisking me to a second hospital with a dedicated lung surgeon to be treated by some of the country’s best infectious disease doctors might have appeared to be more trouble than it was worth.

Whatcha Reading, Dawn McCarra Bass?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they’re digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Dawn McCarra Bass is the Associate Editor of the Seattle Review of Books, as well as a voracious reader and writer. It was fun to hear what she picks up when she's not editing reviews and reading all those long internet articles for the Sunday Post.

What are you reading now?

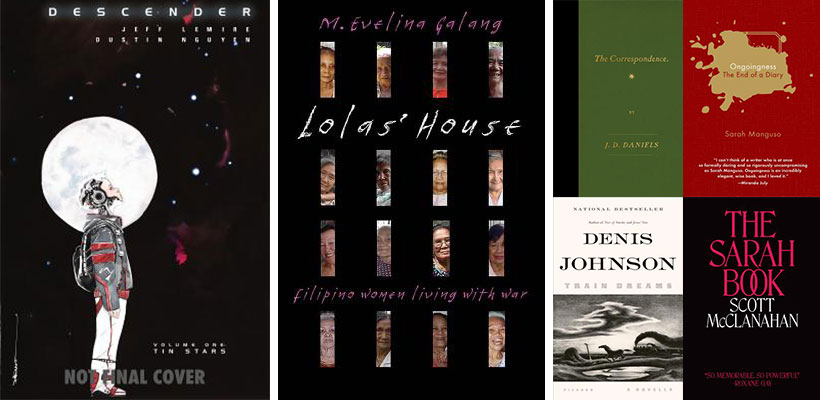

I just started Descender, by Jeff Lemire and Dustin Nguyen. I've been collecting single issues unread since April 2015, apparently. (I have a bad habit of hoarding books I expect will be good — against, I guess, some downturn in fortune when I'll need them. Book of Dust, Acceptance, I'm looking at you.)

I am batshit, batshit crazy about Jeff Lemire; he does loneliness and desolation with exceptional clarity and grace. He doesn’t push self-pity on his characters or ask the reader to feel pity for them — just reminds you how human it is to be lost — whether he’s writing about an over-the-hill hockey player or, in this case, a little boy who’s an android. And the art by Nguyen is gorgeous, utterly signature to the series and yet infinitely adaptable to its moods.

What did you read last?

Lolas' House, by M. Evelina Galang, which captures the stories of a group of Filipino women who were held in Japanese rape camps during World War II. It went on my list while I was working on Donna Miscolta's review and finally made it to the top. It's a hard book to read; I did it in two days, then had a hangover for a week. But it's brilliantly done. Galang intersperses testimonials from the lolas, grandmother-aged women who were anywhere from 12 to 24 when they were abducted, with her own emotional and physical experience both of knowing the women and of re-living their stories with them. Were you inclined to intellectualize, she refuses to let you do it, you have to live it right along with her.

I’m not always able to read the books our freelancers cover, but I like to when I can. Our writers are fucking amazing, and their perspectives are so interesting that I can’t resist going to see for myself.

What are you reading next?

I wish I knew. I have two books sitting next to me right now, and one of them is wrapped up in brown paper with a "Phinney by Post" stamp on it — the first of the year. The other is The Correspondence, by J. D. Daniels, picked after a bit of browsing because it looked like it might fit one of my favorite categories: small, personal, surprising books. Physical format, book design, and guesswork . . . It's how I came across Maggie Nelson's Bluets, Sarah Manguso's Ongoingness: The End of a Diary, Denis Johnson's Train Dreams, Scott McClanahan's The Sarah Book. Also incredible curation by booksellers, of course, who I'm pretty sure "force" them off the shelves like cardsharps.

Mail Call February 9, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

The Help Desk: At your disposal

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

This isn’t book-related, but I like your advice and you seem to have a good head on your shoulders, so I’d hope you’d entertain my question. Is it okay to run food through the garbage disposal even though the city of Seattle runs a composting program? Whenever I flip the switch on some food scraps in my garbage disposal, I always feel like I’m stealing vital nutrients from some plants somewhere. But sometimes the disposal is more convenient! Should I deactivate the disposal completely to remove temptation?

Joe, Portage Bay

Dear Joe,

I'm glad you asked. You can find conflicting reports about whether garbage disposals are more environmentally friendly than other forms of organic waste disposal, so let's not focus on that. Consider this instead: Garbage disposals – or rather, food disposals – are a great example of the economics of laziness that allow capitalist production to flourish in all its illogical glory. Think about their function – using large quantities of potable water to dispose of food scraps that minutes before you were willing to put into your mouth, but that are now unworthy of touching your hands.

No, Seattle isn't suffering from a water shortage but no city is an island and look at the dry and sandy fucking California residents just suffered through – or Cape Town residents are currently bracing for. Do we really want to continue promoting that kind of water use because we can't be bothered to compost?

Buck up and compost, Joe. Or at the very least, deactivate your disposal and install two chickens under your kitchen sink. In my experience, they'll happily eat all your food scrap waste barring onions and garlic casings.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Langston Hughes

Each week, Christine Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Langston Hughes

February 1st would have been the 116th birthday of American poet, social activist, novelist and playwright Langston Hughes. Spend some time with his poems here.

Here in Seattle, we are also celebrating the new non-profit arts organization, Langston, created to continue the mission of the historic Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute and dedicated to cultivating and showcasing Black brilliance.

Future Alternative Past: in need of schooling

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

The best way to learn something

My friend Kristin King asked a while back for book recommendations on Facebook, as you do. But she was looking for something very specific: science fiction dealing with schools. I only came up with two titles for her. First, John Varley’s lovely, haunting, and somewhat contrarian Beatnik Bayou, then my own rather hard-to-locate "Walk Like a Man".

Originally published in George R.R. Martin’s New Voices III anthology, and now available in the 2004 collection The John Varley Reader, Beatnik Bayou tells how a far-future child learns from and eventually outgrows her teacher. The teacher’s development has been artificially arrested at a point beneficial to the student. That part of the job description carries with it a whiff of tragedy — especially as we realize as the story ends that the teacher actually likes the career’s built-in limitations.

“Walk Like a Man” appeared in 2015 in the first and only issue of the wondrous literary journal Bahamut. It takes place in a future school whose primary raison d’être is socialization rather than the imparting of knowledge. Which is why my AI protagonist attends.

With help you can find many more examples, even without expanding the search into other speculative fiction subgenres. Isaac Asimov’s “The Fun They Had,” set in 2157, similarly supposes that learning per se can be imparted without schools; children discover a book describing groups of students attending classes together and dream longingly of sharing the experience.

Lots of school-related SF tales use this Matrix-like template of downloadable knowledge (as when Keanu Reeves declares “I know kung fu!”). Not all of them, of course; Zenna Henderson’s Holding Wonder collection includes short stories based on different plots, such as “The Indelible Kind,” in which a teacher and a student rescue a Russian cosmonaut. The Binti novellas by Nnedi Okorafor take place at an exclusive off-planet university.

Horror typically replicates the awfulness of the compulsory school experience. Stephen King’s Carrie, for instance, details the vindictive bullying and ostracism that sends his telekinetic heroine into a killing frenzy. But The Girl with All the Gifts by M.R. Carey changes that up; it starts off in a school for zombies.

School-centered fantasies such as J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series or Okorafor’s Akata books postulate schools for teaching the practice of magic.

My favorite of this genus is A Wizard of Earthsea, by the late great Ursula K. Le Guin, in which fledgling magician Sparrowhawk matriculates to such a school on the Isle of Roke. I’m also partial to her short story “The Day Before the Revolution.” Though elderly protagonist Laia Odo doesn’t teach anarchist theory formally, classes of all ages take field trips to visit her. She enjoys the company but privately abhors her role as surrogate mother.

Of course “The Day Before the Revolution” would be classified more as SF than F, bringing us back to where we started.

If science can be defined as a way of knowing, then some of these sorts of school-related stories can be considered meta-science fiction. At the very least the overall category merits an additional “s”. A list of readings in SSFFH by Seanan McGuire, Greg Bear, Naomi Kritzer, Caroline Stervermer, and its other authors would make a lovely syllabus.

Recent books recently read

Is Sue Burke’s first novel, Semiosis (Tor) hard or soft SF? It takes place on an extra-solar planet, chronicling three pioneering generations of an Earth-based colonizing effort. But it’s by a woman, and it deals primarily in the “squishy” biological sciences. So, hmmmm.

Even before they land, the book’s colonists are in a jam: their 158-year voyage has brought them to the wrong sun! Failures in on-ship hibernation systems, and crashes destroying a third of their equipment further handicap the enterprise. They forge ahead — what else is there to do? As the colonists adapt to packs of predatory flightless birds and plant-based intelligences, Burke’s title (which my online dictionary defines as “the process of signification in language or literature”) gains meaning and resonance. The author’s clear, straightforward narrative style underscores the intrinsic ambiguity of interspecies communication, and the dangers and potentials of that ambiguity.

How to Stop Time (Viking) by Matt Haig reads like a paranormal romance — think a masculine version of the novels of Deborah Harkness or Diana Gabaldon. Yet it can easily be classified as science fiction. There’s nothing inherently impossible in a genetic mutation that allows its bearers to live 15 times longer than the rest of us. No supernatural abilities are necessary to ensure the successful machinations of Hendrich, who nicknames his fellows in longevity “albatrosses” and uses them to run his murderous errands. The love that binds protagonist Tom Hazard to his 17th century wife Rose, and then again to 21st century French teacher Camille, is completely understandable and human. I was sometimes impatient with Tom’s interiority and fecklessness, but quite pleased at the presence of disabled and nonwhite characters sans unnecessary (in my view) rationales for their existence. A fine and fascinatingly down-to-earth look at longevity.

The Sea Beast Takes a Lover (Dutton) collects short stories by UC Irvine MFA graduate Michael Andreasen. His debut is marketed as both “contemporary fantasy” and “literary fiction.” It could be categorized as what my old writing instructor Howard Waldrop calls “a New Yorker-cup-of-coffee-style story” — if the coffee cup were being held out to you by a tentacle. Yes, you take about the same amount of time to read one of these stories as you would to drink a latte. And yes, per Howard’s annoyed assessment, there are times when protagonists’ situations seem static and their character arcs flat — or as he puts it, “The deer is dead at the beginning of the story and at the end of the story the deer is still dead.” But as you sip you’ll ruminate on greasy-skinned Rocketeers and bodhisattvan baby brothers, on Kerouac-reading mermaids and disappointed adulterers comparing their mistresses’ breasts to raw eggs. Which is not without its rewards.

Couple of upcoming cons

The organizers of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference probably prefer for it not to get lumped in with genre conventions. Academia is the watchword, with works in fantasy, horror, and science fiction considered noteworthy simply because they’re outside the literary mainstream. Panel titles (and it’s pretty much all panels) include “The Mentor/Mentee Relationship for Creative Writers,” “From Thesis to Published Book,” and “Building a Social Justice Curriculum.” I’m there.

Meanwhile, the Outer Dark Symposium on the Greater Weird is also hovering at and around the traditional convention plateau without quite landing there, having approached it from a totally different direction. Abolishing economic boundaries between professional writers and fandom, the Outer Dark asks all attendees to pay their way. The focus on genre edginess and the presence of authors of color such as Craig Laurance Gidney and Silvia Moreno-Garcia are elements carried over from the compellingly intersectional podcast with which it originates.

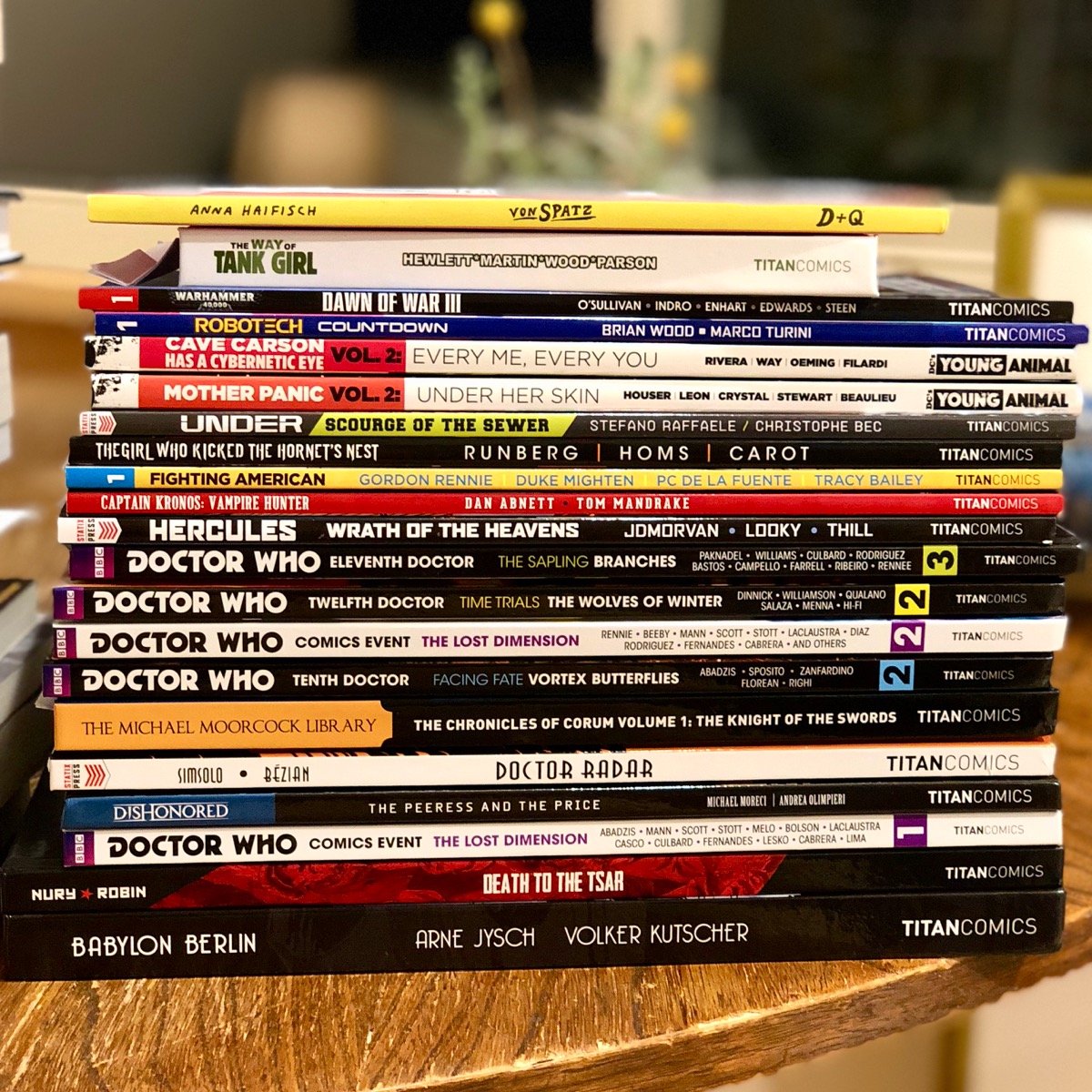

The limits of cartoonomics

Let’s be clear: former Labor Secretary Robert B. Reich is a cartoonist, but his latest title from Seattle-based comics publisher Fantagraphics Books, Economics in Wonderland, is not a comic book. The illustrations in the book aren’t, strictly speaking, comics. They’re cartoons. Perhaps this seems like splitting hairs, but it’s an important distinction: comics involve a juxtaposition of words and illustrations, while cartoons are simply funny drawings that accompany the text without enriching the text.

Wonderland is adapted from Reich’s wonderful series of short illustrated economics lectures on YouTube. Here’s a sample:

Without the actual video of Reich drawing the cartoons, they lose something on the page. In the videos, Reich will often go back and cross out a word or a phrase he previously drew for emphasis. In the book, that word or phrase only appears crossed out, and the impact of crossing it out is lost. Basically, you could read the book without looking at a single illustration and you wouldn’t really miss anything. Which is a bummer.

At the Reading Through It Book Club at Third Place Books Seward Park last night, some of our members were frustrated with Wonderland. They weren’t sure who the book’s intended audience was; was it preaching to the choir, one member asked, or was it supposed to win over conservatives? Why didn’t Reich provide more examples of why a higher minimum wage was a good thing, say, or how more people benefit when we tax the rich at a higher rate?

Speaking as someone who has interviewed Reich and reviewed many of his books, I think some of those complaints miss the mark. Reich is interested in building an economic vocabulary for progressives, to give them an array of cohesive ideas through which they can understand and explain the world. He’s an educator first — his preferred title is “Professor Reich,” not “Secretary Reich” — and not a journalist. He is a gifted lecturer and a top-tier economic thinker, and he’s devoting his talents to explaining middle-out economics to a broad audience.

Some members of the Reading Through It Book Club, though, seemed to think that economics isn’t enough, that Democrats need to do a better job of conveying empathy and why government needs more compassion. And others thought Reich's ideas were a waste of time; one member rejected the idea of Universal Basic Income out of hand, for instance, because he said it wasn’t possible.

And then there’s the question of whether economics can get us out of this mess at all. If capitalism demands continual growth in order to be healthy, can capitalism be considered a truly sustainable system? A middle-schooler with one physics class under her belt could tell you that never-ending growth is impossible. Can we spend our way out of the mess that America has become? We were once promised that automation would create 3-day work weeks for everyone; now we’re told that automation will render millions of jobs obsolete, and we can see that technology has blurred the lines between work and personal life in some very uncomfortable ways.

A number of Reading Through It members loved Wonderland and appreciated the way it made economics — an inscrutable field to them, previously — into something that they could easily understand. I, for instance, appreciated Reich’s description of the way the Federal Reserve maintains the complicated relationship between interest rates and inflation. Throughout the book, people found clarity on matters that previously seemed too complex to understand. In that way, Reich’s talent as a teacher became clear. Everyone learned something, and we had an intense 20-minute conversation about whether Universal Basic Income is a tenable Democratic position for the 2020 elections. Not bad for a book of silly cartoons.