Seattle Arts and Lectures announces the 2018 Prowda Literary Champion Award winners: Mary Ann Gwinn and, uh, the Seattle Review of Books

Every year, Seattle Arts and Lectures honors two members of Seattle's literary community with the Prowda Literary Champion Award. The selection committee includes upstanding members of the community: Elliott Bay Book Company's Rick Simonson; Linda Johns from the Seattle Public Library; local author Jennie Shortridge; Christine Foye of publisher Simon & Schuster; and SAL’s Executive Director, Ruth Dickey. Past recipients include the owners of Open Books, Friends of the Library's Chris Higashi, and Book-It Repertory Theatre. The award is named after SAL's founder, Sherry Prowda, who helped bring national prominence to Seattle's literary scene.

This year's Prowda Literary Champion Awards go to members of the media. Mary Ann Gwinn, who until recently served as the book section editor at the Seattle Times, is the recipient of the individual award. "When I got the job of covering books and authors for the Seattle Times in 1998,” Gwinn told Seattle Arts and Lectures when notified of the award, “I considered myself one of the luckiest journalists alive, because Seattle arguably has the most vibrant literary culture in the country" with its thriving network of readers, bookstores, and librarians.

The other Prowda Literary Champion Award for the year goes to a media organization — in fact, to the website you're reading right now. Foye explains in the press release:

Books are our vessels for these ever-evolving ideas, and it is crucial to shine a light on authors and their books who are exploring and critiquing our culture in the moment. For these reasons, we thought it would be especially appropriate this year to honor Mary Ann Gwinn and The Seattle Review of Books for their remarkable work in bringing rational discourse to the fore in a time of great irrationality.

SRoB cofounder Martin McClellan, associate editor Dawn McCarra Bass, and I are honored by this news. We're humbled to share the spotlight with Mary Ann Gwinn, who has been passionately chronicling the literary life of this city for longer than some of us have lived here. Gwinn has been a true and consistent champion, and her body of work inspires us to do what we do every day.

We'd like to take this opportunity to thank the selection committee and SAL, and also to acknowledge that this award truly belongs to all the people who make SRoB possible: our amazing columnists and contributors, all our fantastic sponsors — and of course, we want to thank you for taking the time to support our sponsors and read our site regularly.

The awards will be given at a fundraising gala for Seattle Arts and Lectures at the Four Seasons on Thursday, March 22nd. Tickets, which support all of SAL's brilliant programs, are available through their site. Maybe we'll see you there?

This May, Seattle will read Yaa Gyasi's Homegoing

This news got buried in the holiday onslaught, and it deserves room to breathe: The 2018 Seattle Reads selection is Yaa Gyasi's novel Homegoing.

Seattle Reads is the Seattle Public Library program formerly known as If All Seattle Read the Same Book. Basically, the library gets a ton of copies of the book and hosts the selection's author in library branches around the city. It's an attempt to focus conversation and encourage civic discourse around the topic of a single novel.

Homegoing — a novel about two sisters born in eighteenth-century Ghana who live completely opposite lives — is a sensational choice, and a higher-profile selection than some of the recent Seattle Reads selections. The book has won awards from PEN and the National Book Critics Circle, and it was featured on many best-of-the-year lists. SPL says the book "illuminates slavery's troubled legacy both for those who were taken and those who stayed-and shows how the memory of captivity has been inscribed on the soul of our nation."

Copies of Homegoing and related book club materials will be available through Seattle Public Library in the middle of February. Gyasi will visit Seattle in May for a number of personal appearances. Get started on the book now so you can be a part of the conversation this spring.

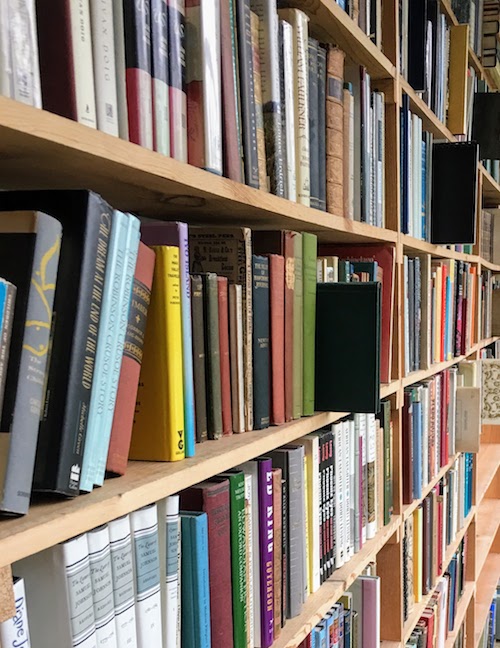

Louis Collins, a titan of the antiquarian books scene, has passed away

You could find books on the shelves at Louis Collins's Capitol Hill bookstore that existed nowhere else on earth.

Last night, the news started spreading on Facebook that Seattle used bookseller and Seattle Antiquarian Book Fair cofounder Louis Collins had died. Collins reportedly collapsed while walking his dog yesterday and had passed away before medics could arrive. By this morning, Collins's Facebook page was filled with loving tributes posted by friends and antiquarian booksellers from around the world.

Collins got his start as a bookseller in San Francisco, using his remarkable memory as a resource for customers who were in the market for specific rare titles. He worked as a bookseller for nearly a half century, right up until the day he died. For many decades, he sold books under the Louis Collins Books shingle out of a little blue house at 12th and Denny on Capitol Hill. He finally sold the property last year and moved to the north end of the city.

For a bookseller who made his name as a kind of human Google in an analog time, Collins adapted surprisingly well to the computerized age of bookselling. “I liked the idea of computers” before the internet, Collins told me, and he claimed to be the first bookseller in the city of Seattle to have his own website. Collins cultivated a hugely impressive collection of titles that couldn't be found anywhere else online, and he regularly shipped those books to loyal customers around the world.

He deeply enjoyed working as a bookseller, but the Seattle Antiquarian Book Fair was a true labor of love. (The Book Fair has, for purposes of full disclosure, been a sponsor of the Seattle Review of Books since this site's inception.) When I interviewed him in 2016, Collins told me with no small amount of pride that while the doors of the Book Fair are open “it’s the best bookstore in America.” And at the end of the weekend, “when everybody packs up and goes home, it’s gone.”

Collins deeply believed in Seattle as "a great book town" with "great bookstores." Even when he worked as a bookseller in California, he would make frequent trips up to Seattle to buy books from our great readers. “There have always been very good customers here,” he told me. It was here in Seattle, among our readers and our collectors and our lovers of books, that he felt most at home. We will miss him greatly.

An exit interview with Shin Yu Pai, the outgoing Poet Laureate of Redmond

What does it mean to represent a city, or a state, through poetry? To me, the role of poet laureate always felt like it would be too much responsibility. Writing a book of poetry is one thing, but to represent the varying perspectives of a community through poetry seems like a daunting task of representation. Seattle poet Shin Yu Pai talked to me over the phone last month about her tenure as Redmond's Poet Laureate — what she learned, her successes and failures, and what she thinks her legacy might be. To learn more about Shin Yu Pai, including samples of her work and upcoming events, visit her website. She reads next at Elliott Bay Book Company on Saturday, January 13th.(Photo of Shin Yu Pai at the "Heyday" video unveiling by James McDaniel.)

You're one of the most thoughtful poets in the Northwest, and I was wondering if your term as Poet Laureate of Redmond provided you with any insights into what being a poet laureate, what representing a city as a poet, means to you. What did the experience teach you?

I learned a lot about what the work of doing public art is like, and what skills are involved in doing that. I worked collaboratively with individual artists and designers, and even companies. Working on a larger scale — working with a community or city — was a new kind of experience for me, and I found that there were different kinds of skills that needed to be brought forward in my own work and ways of managing projects that I needed to be more flexible with: scopes of projects, timelines, and so on.

Those are the things that, over time, informed the way that I went about the work. I made certain pieces knowing what kind of iterative processes they might need to go through before they could be presented or shared. Those were good lessons for me, because for a work to really reflect a community — and for a work to be conversation and collaboration — those things take more time, and a lot of back and forth.

A lot of your work in this project has involved nature. I’m thinking of the leaves and your animated poem “Heyday,” about the Redmond history of logging. You know, nature is probably not in the top three things that a Seattleite thinks of when you ask them about Redmond.

So Seattleites probably think of Microsoft and rocket technology when they think of Redmond. And those things are absolutely true, and they're stereotypes, too. They've still got farmland [in Redmond,] and there's still parts of it that feel very unspoiled to me.

For me, exploring Redmond became this exercise in really wanting to see what the city is: its history, its place. Certainly there's the city — the contemporary technology and what makes it the place that it is now. But I wanted to very much ground that with the physical geography of what Redmond is.

And that’s what drew me to the bike trails, and really interpreting the history and what the city is known for in terms of its archeological significance, alongside famous residents and contemporary people who were important to this city. That was a very intentional gesture, looking up historical records to really look at the past of Redmond, and bring it alive and animate it.

I didn't really have many thoughts about Redmond when I moved here because I don't drive, so I almost never made it out there. But then I started walking, and I wound up walking to Redmond a lot, and I really dig it. I like all the bike trails, and then as I've learned more about it I like what I’m learning. The mayor has been very progressive, and very interested in making the city ready for transit, in a way that other communities outside of Seattle haven't really done. And politically, of course, there's Manka Dhingra, who’s just turned Washington state’s legislature blue for the first time in a while. It’s interesting to me that you don’t live in Redmond but you’re representing Redmond. What was your exploration of the city like?

Yeah, so, it's been a series of visits. Usually they’re built around exploring a certain site. The Heron Rookery was one place that I harvested leaves from, and the Farrel-McWhirter Farm Park. And I also explored the organizations that are there. I've had a couple of really great partners in the Redmond Public Library, in VALA Eastside, in the Senior Center. It’s been a slow and gradual exploration from a distance.

I will admit, honestly, that I think that living here in Seattle — and I don't drive much either — it was a challenge to be more deeply immersed as a Poet Laureate. And I actually think that as they're looking for a new Laureate, they should probably consider somebody from the eastside.

But, I don't think that was necessarily a barrier or deterrent in eventually hitting my stride

One of the things that I did last year for National Poetry Month was to curate this celebration of poetry and song. And so, I brought together people like Jessika Kenney to perform traditional Persian and Middle Eastern music with a performer from Kirkland named Srivani Jade who sings Mira Bai poems.

And it was really exciting to see that the audiences that were coming out for some of these programs were quite different than what you would see at Seattle openings or Seattle readings. Redmond is a city that is very much made up of many immigrants from Southeast Asia, and it was really great to be able to draw some of those folks out with some of those things I'm trying to do.

You've always been a very collaborative artist, but it seems to me that the act of being a Laureate involves a sort of elevation of other artists. Was there a learning curve to finding people and to curating the Laureate experience?

Yeah, certainly in some of the technologically sophisticated projects I wanted to do. I collaborated with the textile artist, Maura Donegan, who is from the east side, on this poetry embroidery project that was a response to a hate crime that happened in Redmond. And it took me a while to find Maura, because I had sort of gone down this path of wanting to figure out a way to digitally fabricate the piece that I made that was basically an embroidered broadside in multiples. But that was a very complicated and expensive process, so ultimately I engaged Maura to just make me one big textile piece that she basically sewed herself.

It was a challenge to find her, and VALA Eastside really helped to direct me towards her. And, with this last piece that I'm doing — this video projection — it took time to figure out who had the technical knowledge. I needed to find a designer who could do animation, and then I needed to find somebody who could help me with the logistical specifications of projecting onto the side of a building at night. So, I've been really lucky through Seattle networks to know who those go-to people can be, to help me create that work.

So, the learning curve, I would say, was pretty steep. Because there are lots of people that I know in my creative network here, but I also felt like the particular projects that I was working on required a certain kind of sensibility.

I wanted to ask you specifically about the textile work, because I don't know if I have seen other Poets Laureate be that, sort of, immediate? It seemed, to me, to be a mix of poetry and visual art and journalism. What a Poet Laureate should do is console in times of tragedy and investigate what the tragedy means to the community. And that seems like, just such a unique moment and unique piece.

Yeah, I'm really grateful that you asked about it. It's a piece that's important to me, and I wasn't able to share it or fabricate it for over a year.

So, I wrote the poem in early 2016 — I want to say in January or February of last year. It was this a crime that you may have heard about in Redmond. It involved a woman named Leona Coakley-Spring, who is a Black business owner and had this small consignment shop, which was called Rags to Riches.

She was running her business and there was a young man who came in, acted really suspiciously, said he wanted to consign some clothes with her. He ended up leaving, and he left behind a couple of garments in bags. And so when she went to look through them to try and identify if she could return the materials and garments to him, she wasn't quite sure what she was looking at. But when her adult son came and looked at the materials, what they discovered was that this young man had basically abandoned a Klu Klux Klan robe.

That was this really, really heavy thing. I remember reading about it in the news and being so shocked and appalled — that in this present day, so close to where I live, that this was happening.

Yes.

And, you know, a KKK robe is a very potent symbol whether or not you're a black person or not.

And it's such a specific crime, with such a personal level of premeditation to it There’s such a weird intentionality to it. You know, you hear 'hate crime' and you think of, like, graffiti or something impersonal like that, but this feels so direct.

It was very threatening. It was very disturbing to me. It was this clear message of like, "Go back to where you come from." You know?

And so, it really demanded or called in me this reaction to express some sort of solidarity or compassion — some kind of response. And so I wrote this poem and I hoped to share it with the community at that time, but because this was under investigation and the poem included details of what had happened, the city determined that we couldn't share it with the public, because it was an active crime investigation. And that investigation went on for a few months, but ultimately they weren't able to track down the individual that left those items, and Ms. Coakley-Spring ended up closing her store, and the robe was somehow returned to her. I don't know if it was taken in as evidence for a time or if she always had it, but I read a story in the news about her burning it.

That was this really powerful moment too, because I had had this whole plan that I would try to connect with her and ask her if I could have the robe so that I could embroider it or do something with it, and use it as kind of the basis of the response that I wanted to make. And so that didn't work out.

I thought about an embroidered broadside, and that didn't work out budget-wise. And so then, we made the textile, and that was actually shown this summer at the So Bazaar Festival. I partnered with VALA Eastside, which is this gallery in Redmond, and we talked about the idea of putting together an interactive poetry embroidery booth. We wanted to use the broadside that Maura and I had made together as kind of an example of what people coming to the festival could do. They could sit down at this booth with embroidery hoops and cloth and thread and needles, and basically do embroideries themselves and come away with something that they could take home or feel proud of.

And so I curated language out of Redmond's Inclusion Resolution, and I also took language from poems by Elizabeth Alexander, who's a former Obama inaugural poet, and Langston Hughes and some others, that all dealt with inclusion and tolerance in some way. And then we basically mocked them up so that people coming to the booth could stitch those as kind of their sampler. The intention behind the booth was very much to engage regular citizens in this specific dialogue around inclusion.

Book News Roundup: While you were on holiday break...

Over at the South Seattle Emerald, librarian Maggie Block published a spectacular roundup of radical books for young readers. You should read all three parts.

Aside from the sad news of Sue Grafton's passing, the biggest book news of last week was the publication of editorial notes for Milo Yiannopoulos's book. An increasingly exhausted editor from Simon & Schuster left a series of increasingly angry notes on a draft of Yiannopoulos's book, and now that whole document has been entered into the public record. (Simon & Schuster dropped the book after several of Yiannopoulos's pro-pedophilia comments came to light; the author is now suing the publisher because he is a massive bore.) The editorial comments are funny and satisfying to read, but you must remember that at the heart of it all, what the editor was trying to do was to make a racist shitbag palatable to as wide an audience as possible. I read the editorial comments as their own separate narrative: that of a man who hired a monster and then slowly realized exactly how monstrous the monster was.

Barack Obama released his list of favorite books from 2017 on Facebook, and it's great. I especially love that President Obama agreed with me about Janesville, which is one of the most underappreciated books of the year. Obama also read Evicted, which wowed the Reading Through It Book Club about five months ago.

Marvel Comics released an official fanfiction creation service, but the restrictions are so dumb that nobody will ever use the thing.

Marvel Create Your Own reserves the right to revoke access to the service for any content including — to name a few — “Content that could frighten or upset young children or the parents of young children,” “contraceptives,” “bare midriffs,” “noises related to bodily functions,” “misleading language,” “double entendres,” amusement parks other than Disney parks, movie studios not affiliated with Marvel, animated movies not made by Disney or Marvel and depictions of tobacco, nudity, gambling, obscenity and “proxies” for obscenity such as the comic book shorthand of bursts of punctuation instead of curse words.

- In Canada, the works of Langston Hughes and Dorothy Parker entered the public domain yesterday. In America, we continued our shameful public domain drought. The public domain needs to be continually refreshed with new works, because the creepy Ayn Randian ideal of an artist who makes everything up in her head is a fiction. Without a wellspring of ideas to inspire new artists, the collective creative unconscious will wither and die. Copyright control is creation control.

Alphabetical order

Published January 02, 2018, at 11:52am

When Sue Grafton died last week, she left a remarkable series of books behind: complex but accessible, comprehensive yet entertaining. And her hero, Kinsey Millhone, is one of the liveliest private investigators you'll ever meet.

A Few Preexisting Conditions

We drank too much.

Stayed up too late

watching elephants disappear.

The beer was flat. The ice

receded. The moon

tracked its footprints into the house.

Bases loaded, the batter struck out looking.

The kicker shanked the field goal wide

to the right. The wide receiver took a knee.

The drone strike found its target.

The drone strike missed its target.

The drone strike turned the village to dust.

We stood in line for hours

waiting to vote.

We stood in line for hours

to procure a gallon of gas.

The hurricane struck out looking.

The hurricane stripped our limbless roofs.

The car swerved into oncoming traffic.

Traffic thickened in our veins.

The DNA test came back negative.

The DNA test came back positive.

The father never came back.

The father started smoking again

after the heart attack.

We ate too much red meat.

We ate too much corn syrup.

Our vote wasn’t counted after all.

Our vote was packed into safe districts.

We lost track of the days

we didn’t have to work overtime

to make rent. The rent woke up.

The rent went up in smoke.

We ignored the lump in the lymph node.

Doctors hit the lymph node hard.

Not our doctors. Too expensive.

Someone brought us a pot pie instead.

The dog ate it. The printer jammed.

Dandelions took over the yard.

Smoke took over the sky.

We drank too much. The world was flat.

Poachers took out the last rhino.

Few understood the news.

Resolve not to miss author Anne Lamott in April at Benaroya Hall

This will be a good evening for writers and readers both: for followers of Lamott's Bird by Bird writing guide (who are legion), and for lovers of her thoughtful, direct, and funny novels and essays. Start the year right by putting this on your calendar — you'll thank yourself later. Get more information on our sponsor’s page, or buy tickets here.

We just realized that both Christmas and New Year's day here at the Seattle Review of Books were sponsored by Northwest Associated Arts. Thank you for the making our holidays bright, NWAA! And a huge thank-you to all of our 2017 sponsors. We're grateful for each and every one of you.

If you're interested in joining our community of sponsors (who are, really, the best) — and putting your book or event in front of our readers — check out available dates in 2018. We'd love to meet you.

Photo credit: Mark Richards.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from January 1 - January 7

Monday, January 1: Third Place Books Sale

Happy New Year! Every book at every Third Place Books location is officially 20% off today. I can't think of a better way to kick off a new year than coming home with a big stack of books. Can you?

Tuesday, January 2: Wayward Readers Society

This fall, Seattle author and comics writer G. Willow Wilson announced that she’s publishing her second novel, The Bird King, with Grove Atlantic. This book club is a perfect excuse to go back and reinvestigate Wilson’s fantastic first novel, Alif the Unseen. Alif is about a hacker in a security state, and it combines religion and tech and adventure into a thrilling page-turner of a book. Go geek out over it with some potential friends. University Book Store Mill Creek, 15311 Main St., 425-385-3530. http://ubookstore.com, 6:30 pm, free.

Wednesday, January 3: Reading Through It

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, January 4: Answer(Me) Reading

After publishing two books last summer, Seattle Civic Poet Anastacia-Renee debuts her newest book tonight. It’s called Answer(Me), and like most of her work, it’s raw and honest and confrontational and gorgeous. Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Friday, January 5: David Sedaris Workshop Performances

From this Friday to Thursday of next week, Sedaris is reading eight times at Broadway Performance Hall. He’s workshopping his next collection, Calypso, which comes out in summer of this year, and he’s counting on Seattle to help him make it perfect. Broadway Performance Hall, 1625 Broadway, 934-3052, 7 pm, $50.

Saturday, January 6: You’ll Miss Me When I’m Gone Reading

In Seattle author Rachel Lynn Solomon’s new young adult novel, a pair of identical twins take a test to find out if they have Huntington’s disease. One set of results comes back negative. The other comes back positive. Will this prognosis tear them apart? University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 3 pm, free.Sunday, January 7: Snow Sisters! Reading

Kerri Kokias’s new picture book for kids is about sisterhood and snow days. “Just like snowflakes, no two sisters are alike,” promotional copy tells us. The book follows each sister individually on their winter adventures, and then brings them together in the end. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 2 pm, free.

Literary Event of the Week: Reading Through It Book Club at Third Place Books Seward Park

The second year of the post-Trump book club founded by the Seattle Review of Books and Seattle Weekly officially begins this Wednesday at Third Place Book Seward Park.

This month, for a change of pace, we're talking about something not specifically related to Trump, Russia, or the Republican Party. Instead, our choice, Cathy O'Neil's Weapons of Math Destruction, is about the rise of data and algorithmic systems. It's probably hard for you to place a priority on data management when the whole world is falling apart around you. But O'Neil argues that our faulty mechanisms of data management are exacerbating our problems.

Obviously, algorithms are responsible for the spread of "fake news" on Facebook, and the ability of Russians to interfere with the outcomes of the 2016 presidential election. But O'Neil points out that data can enhance pre-existing structures of racism and classism, creating a negative feedback loop that accidentally "proves" the problems that data collection is intended to solve.

This is important stuff, and it will be a big part of the conversation as we move toward the 2018 midterm elections. Weapons of Math Destruction is available for 20% off at Third Place Books right now, though no purchase is necessary to join us for the book club. I hope to see you there.

The Sunday Post for December 31, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

By an accident of timing, the Sunday Post has the last word on 2017 at the Seattle Review of Books.

When I agreed to collate this weekly list, it was just after Donald Trump’s election; the news cycle hadn’t yet shifted into something past lightspeed. Truth was still truth, more or less, and powerful men weren’t monsters, or at least we weren’t yet saying so out loud. We knew that Donald Trump was a racist and that his election represented something ugly embedded in this country. We didn’t understand — those of us who had the privilege not to already live and breathe it — how ugly and how deep.

As happens after a visceral blow, we were numb for a while, huddled under shock blankets and waiting for the pain to hit.

Then it did hit, hard. And writing on the internet became a firestorm of Trump-centered emotion and analysis: grief and fury, resignation and defiance, reflection and contention. Much of that writing is stunning in its depth and force.

And yet, and brilliantly, people still committed millions of words and images to simply celebrating the oddity and beauty of the world.

And yet, and brilliantly, people still committed millions of words and images to simply talking about things like books.

By treating words and ideas and books as if they matter, these writers ensure that words and ideas and books continue to do so.

So: Usually the Post covers writing that happens off the site. But I’m ceding the last word of 2017 (here at SRoB, at least) to the reviewers, poets, artists, and essayists who wrote about books for the Seattle Review of Books this year. Each of them, in their own way, transformed the fire around us — took the heat, and turned it back around.

A year in reviews

Robert Lashley wrote eloquently and with passion about Ta-Nehisi Coates’s We Were Eight Years in Power and showed us the thoughtful, personal, eloquent book obscured behind cheap shots and hot takes.

Sophia Shalmiyev’s review of Eileen Myles’s Afterglow was breathless and reckless and startling and perfect.

Donna Miscolta wrote several pieces for us this year, but her essay on the language of rape and M. Evelina Galang’s Lolas’ House is the one that left us speechless, which believe me is not easy to do.

Kelly Froh and Siolo Thompson reviewed books by drawing comics, which is maybe the coolest thing ever.

Contrariwise, Colleen Louise Barry and Jessica Mooney reviewed comics by writing words. Both of their pieces are standouts: Barry’s review of Jason T. Miles’s Lightning Snake adeptly captures the book’s disorienting disjointedness. The opening to Mooney’s review of Kristen Radtke’s Imagine Wanting Only This is heartwrenching, and her exploration of why we’re drawn to decaying things is perceptive, empathetic, and smart, smart, smart.

Nick Cassella, in his review of Richard Reeves’s Dream Hoarders, and Jonathan Hiskes, covering Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement, tackled some of the terrifyingly large social and environmental issues of this year (and unfortunately, but unquestionably, the year ahead).

Samuel Filby looked at Maged Zaher’s Opting Out through the lens of Richard Rorty’s Philosophy as Poetry through the lens of Socrates and Derrida. A knowledgeable and wide-ranging brain-bender of a review.

“If you have never been close to death, then this book is probably not for you.” That’s Dujie Tahat on The Crown Ain’t Worth Much, by Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib, reminding us that poetry is in no way distant or distinct from real life, and pushing hard on our assumptions about the Black Lives Matter movement as he does it.

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore interviewed Anastacia-Reneé about violence, injustice, and our home city. Ivan Schneider interviewed David Shields, then wrote him a long letter about talking dogs.

And Anca Szilágyi, whose Daughters of the Air was just released, explained why we’ve all been thinking about translation in the wrong way — in an essay that includes one of my favorite lines of the year, and perhaps the best possible close to 2017: “To all this I say: poppycock.”

A year in verse

The fact that our year in poetry started with battle, with Elisa Chavez’s “Revenge” (“rest assured,/anxious America, you brought your fists to a glitter fight”), and ended in a hot bath, with Sarah Jones’s “When I finally get that claw-footed tub” (“the heat a rising redemption/misty and heaven-bound”), makes me gleeful — they’re the perfect bookends (sorry, couldn’t resist).

This year the site was graced by an incredible range of Poets in Residence: in addition to Chavez and Jones, JT Stewart, Jamaica Baldwin, Joan Swift (posthumously), Oliver de la Paz, Tammy Robacker, Kelli Russell Agodon, Daemond Arrindell, Esther Altshul Helfgott, Kary Wayson, and Emily Bedard. If you haven’t been following the Tuesday poem, top off your cup and catch up now.

A year in columns

Our columnists have a regular platform to talk about what they love — explain why it matters, and show us how the world looks through its lens, even when that world is run, seemingly, by a madman with bad hair.

Nisi Shawl’s Future Alternative Past is a masterclass on SFFH. Her knowledge of the genre is comprehensive, and she approaches it with a completely fresh critical lens and a fine eye for relevance. See, for example, her column on fat positivity in science fiction.

Olivia Waite’s Kissing Books touches on race and feminism and socioeconomic issues — all the hard, smart ideas that romance novels are supposed to not contain but do. And her takedown of Robert Gottlieb was epically excellent.

Daneet Steffens’s Criminal Fiction is a monthly reminder that reading is a pleasure. The joy she takes in what she reads is evident in every capsule review and interview.

- Whoever your favorite author may be, you’ll love them a bit more after Christine Marie Larsen captures them in a portrait. (For me, it's this one of G. Willow Wilson.) Her talent for conveying the kindness, compassion, and humor of her subjects is very welcome in these angry times.

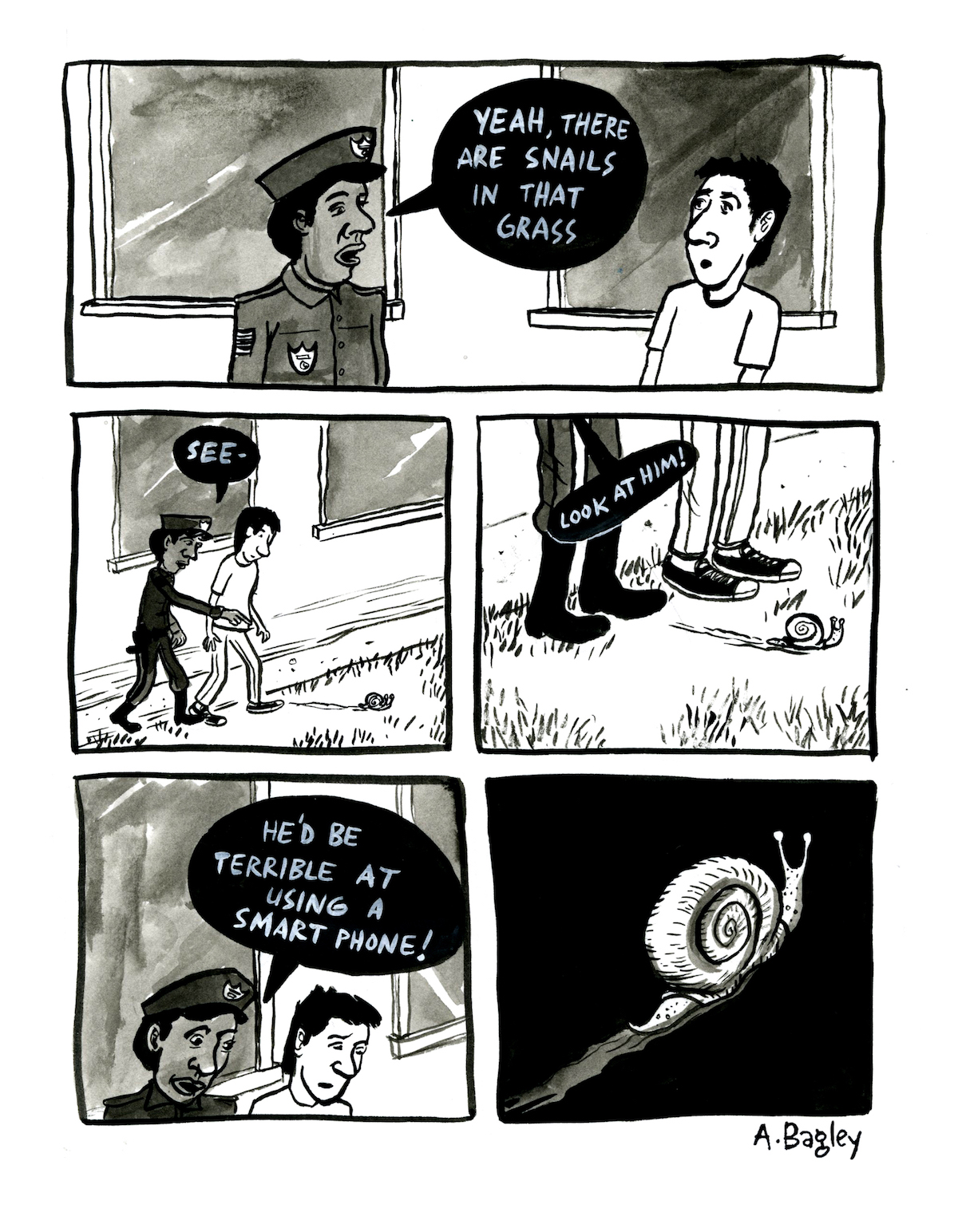

Two new columnists started sharing their pen-and-ink perspective on the world at SRoB this year: Aaron Bagley’s Dream Comics are charming and odd and full of import; this one is about whales. Clare Johnson’s Post-It Note Art is quiet and personal and expressive far beyond the boundaries of a three-by-three square.

Nobody addresses humanity’s relationship with the written word, and all the shame and social awkwardness and anxiety it provokes, as regularly and accurately as Cienna Madrid in the Help Desk.

Oh, right. Martin and Paul.

- Did you know co-founder Paul Constant likes to walk? He does. He walks and walks and walks. His review of Neal Stephenson’s Seveneves talks about why, with characteristic clarity and piercing lyricism.

- Did you know co-founder Martin McClellan was in a band? He was. For the Thanksgiving essay this year (yes, that’s a thing, and so is the Christmas ghost story), he talked about a country earwormed by Donald Trump. And then he gave us a playlist to survive to.

Seattle Writing Prompts: New Year's Eve at Seattle Center

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

Every year at the stroke of midnight, December 31st, the Space Needle explodes. It's a controlled explosion, and doesn't hurt either the Needle or anybody atop it. It does entertain the huge crowd of people who come to Seattle Center every year to celebrate ringing in the New Year: Seattle's version of Times Square.

One year, it didn't happen. December 13th, 1999, a guy named Ahmed Ressam is on a ferry from Victoria to Port Angeles. He'd already passed through customs, but the way he was acting caught the eye of US Customs inspector Diana Dean, and she decided to have another talk with him. They inspected his car and found bomb-making materials. Ressem fled on foot and got six blocks before they took him down.

Remember that this was before September 11, 2001. Terrorist attacks had happened on American soil, but the only people scared of them were the people in charge of stopping them.

And Seattle Mayor Paul Schell: Although Schell is best known now for being the mayor under the WTO riots, and for being assaulted by Omari Tahir-Garrett, he was considered an establishment city builder. He moved a lot of money around Seattle, helping to grease the wheels to get the new City Hall, the new Library, and the new Opera House built.

He also cancelled the Seattle New Year's Eve millennial celebration. He was called a "schoolmarm" by local artist Carl Smool. Mr. 9/11 himself, Rudy Giuliani, said "I would urge people not to let the psychology of fear infect the way they act, otherwise we have let the terrorist win without anybody striking a blow." Ahem. lol.

But a missing propane truck at the time, and the very real threat from the border crossing, combined with a year where the WTO roiled the police (who were then further demeaned by a death at an overly raucous Mardi Gras celebration) lead Schell to take a bold and unusual step for a mayor: shutting down the big party on the eve of the millennium.

The only party open: a private party at the Space Needle, for those who paid well, far in advance.

Perhaps Schell was acting out of an abundance of caution — there was no known risk that night. But after the attacks on 9/11, everybody looked back a bit differently at the cavalier attitude people had toward security way back when.

The streets of Queen Anne were quiet that night. It makes me wonder about alternate realities. It makes me wonder how many stories that night continued, in spite of the cancelled event....

Today's prompts

It started with the mayor canceling New Year's. They had a huge argument. He started it: "New Year's is ruined," he said, "because of our pansy-assed mayor and his lick-ass council. If this city had any balls they'd just throw the middle finger at terrorists and say 'come bomb us, assholes!'" Her attitude was more one of "there are plenty of parties to be had, and if you let this ruin your millennium, then you are a fool, and why are we even in a relationship?"

If you want them to stay together this night, go to prompt 1. If you want them to separate (and follow her), go to prompt 2.

He picked the party, at his friend's house, in the end. They argued all the way there, all the way inside, and all the way to the kitchen where he did four shots and cracked a beer with his buddies, leaving her to fend for herself. She found a beer herself, and checked out the house. It was a series of rooms with gross carpet and broken furniture, anywhere you might care to sit stained or wet with spilled alcohol. It was worse than a frat house. She went to use the restroom, then thought better of it and went back to the kitchen to beg him to leave. He wasn't in the kitchen. None of his friends would say where he went, but one of them kept looking at the back door. She went to it, looking through the glass, but all was darkness. She flipped on the light, and there, under a naked 100 watt bulb, was her boyfriend making out with some slag. If you want this to turn into a science fiction story, go to prompt 3. If you want this to turn into a horror story, go to prompt 4.

A few calls after leaving his apartment, and she was in a cab to meet up with some friends at a bar downtown. "God, we're so glad you lost him," said one. "He was really an asshole, and not even hot enough to make up for 10% of it." They bought her drinks, and were trying to get her to talk to other men at the bar, including one who looked like a young Jeff Goldblum. They talked, and he said "look, this is crazy, but I've got two tickets to the final hour of the century at the top of the space needle. Do you want to go?" Before answering, her phone rang. She stepped out to take the call from her very apologetic boyfriend who begged her to come back. If she should reunite with her boyfriend, go to prompt 1. If she should go to the Space Needle, go to prompt 5.

"Oh my god, what an asshole" said a voice. She turned to see her, a woman she'd met a few times, who lived in this house with this guys. "Come with me." The roommate took her hand and led her upstairs, where, behind a locked door, was a nicely appointed master suite. "Your room is actually....clean. And normal." — "Oh, yeah, the whole house is usually. I just rent crappy furniture for the parties so my nice stuff doesn't get ruined." The roommate took her through a doorway into another room, where lights blinked in the darkness. The overhead lights came on to reveal walls of computers. "Get your mind off that asshole," the roommate said. "Try this." She held out a band. It was supposed to go around her head, with two spoon-shaped devices that apparently went over her eyes. "If you put this on, it's gonna transport you into another person, at the Space Needle tonight. I've been hacking into their brainwaves all night. Time to crash the richy-rich party, yeah?" — "Uh sure, I guess." She put on the device, and her head felt like a leg that went to sleep and got woken up to pinpricks. Then, suddenly, she was in someone else's head. Go to prompt 5.

She was about to open the door and punch somebody, when the clouds parted and the moon came out. The girl kissing her boyfriend jerked, and fell backward, and she was out of view. A moment later something came up. Her boyfriend recoiled, but a canine snout bit at his face, and tore his nose clean off. Blood splattered the window, and she turned to the room, only to find everybody in it also, now, werewolves. Hungry spittle dangled from sharp canine teeth. Growls and yelps came from all corners. All those drunk assholes, now drunk werewolves! She was trapped — the shewolf on the porch now baying and howling at the moon, the others in the kitchen now coming towards her. She dived for the paper towels, lit the stove and made a torch, waving them back. She managed to get to the living room, and made a break for the door. She had her hand on the knob, when a bite took her heel. She went down, crying out loud, another victim to the werewolf outbreak of 1999 who didn't live to see the millennium. Fini.

There were ten people at the table, and she was sitting next to the host who brought them all together, the young Jeff Goldblum-looking guy. He was paying for the whole thing, apparently, and here she was, his awkward new date. She expected him to be grabby or expect something, but in fact he was funny and charming, and never crossed a boundary with her. She thought about her jerky boyfriend, and leaving him behind seemed like a week ago, not hours. She talked to the host about his job in tech, and he looked right at her when he talked, like he was really interested in her. When the fireworks went off — so loud inside the restaurant! — he sang auld lang syne and laughed. She asked to kiss him. Fireworks. Not a bad way to start a new millennium.

The Help Desk: Does Buzzfeed count as reading?

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com. The following column was originally presented on December 4th, 2015.

Dear Cienna,

Please settle a bet. My friend says our culture is spiraling toward illiteracy. He thinks we're devaluing language to a point where we'll soon only communicate through pictures, or video. I think we're more literate than ever before. I read more every day than I ever have in my life. Of course I read more websites than books, but I'm of the opinion that reading is reading. So who do you think is right? Are we becoming illiterate, or are we more literate than ever?

Fran, Redmond

Dear Fran,

Sure, more people may be able to fulfill the most basic definition of literacy but I disagree with you that "reading is reading." Like butt implants and Bible interpretations, reading varies wildly depending on the source. Is it great that a higher percentage of Americans can functionally read words, a necessity formed by our texting, emailing culture? Yes, but that doesn't mean they're critically engaging with what they read, or that the writing our culture is currently producing inspires intellectual curiosity (I'm specifically thinking about the sad state of journalism, which would best be encapsulated by a gif of people eating popcorn at the site of a grisly car crash. Also beautifully summed up today by this debacle). As for your friend, please tell him or her that their argument is based on a false premise: words are not a cash commodity that can be devalued or replaced. For instance, there will never be a picture that can convey specific words like "lugubrious" and "malady" or even "uranium," which in pictorial form just looks like moldy bread. Since you are both wrong, I win your bet. You owe me a critical 500-word essay responding to an interesting article you've read recently and your friend owes me $20 and a gif of people eating popcorn at the site of a grisly car crash.

Please send both to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Kisses,

Cienna

2017 in review: The non-fiction books that made my year

I don't really have "favorite" books. I read too much, and I read too widely, to believe that any one book can encompass the totality of my tastes and reading experiences. Similarly, I think best-of lists are absolute bullshit. The only reason anyone ever made a list was because they wanted to start a fight. But here we are in the last week of the year, and I do think that some reflection is worthwhile. This week, I'll highlight some of the books by local authors that made my year in reading so memorable. Today, the focus is on non-fiction.

A lot of the best non-fiction I read this year was by non-Seattle authors. Patricia Lockwood's Priestdaddy blew my mind with the way it nonchalantly tore apart the memoir tradition and created something new. And Amy Goldstein's Janesville was one of the most interesting and informative books about the problems with American politics that I read this year.

It wasn't a banner year for non-fiction, locally. There were some well-researched histories and a few cultural books released by local authors that were pretty good. These three books stood high above all the rest as testaments to the Northwest tradition of storytelling.

The fact that Fantagraphics had to publish the definitive history of Fantagraphics — a massive book called We Told You So will always strike me as a shame. I wish someone else would want to record the life and history and legacy of the greatest comics publisher in the world. But Fantagraphics went and did it themselves, and the book is fun and funny and gossipy. It will make you want to cast your life aside and take up the monklike tradition of publishing. And then you'll likely come to your senses, and not a moment too soon.

Seattle Times reporter Claudia Rowe's The Spider and the Fly is a true crime book that looks inward. Rowe writes about her personal interactions with a horrible serial killer who likely only killed for as long as he did because the prostitutes he killed were beneath society's notice. Some readers will likely find the memoir pieces of Spider to be frustrating, but that's only because they're looking for a generic true crime formula. Instead, Rowe is piecing together her own history after deeply examining the history of a genuine monster.

Sherman Alexie's memoir You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me is tender and hilarious and harrowing. It's about one of the worst years in Alexie's life, and it made 2017, which is likely to be the worst year in many people's lives, a little more survive-able. Alexie's writing is so readable that many readers fail to notice the intricate structures and deeply thoughtful construction that goes into the book. This is one of Alexie's very best books, which means it's automatically one of the best books to come out this year.

Portrait Gallery: Happy Birthday, Nichelle!

Wishing Nichelle Nichols a very happy 85th Birthday!

Thursday Comics Hangover: 2017 in review

I don't really have "favorite" books. I read too much, and I read too widely, to believe that any one book can encompass the totality of my tastes and reading experiences. Similarly, I think best-of lists are absolute bullshit. The only reason anyone ever made a list was because they wanted to start a fight. But here we are in the last week of the year, and I do think that some reflection is worthwhile. This week, I'll highlight some of the books by local authors that made my year in reading so memorable. Today, the focus is on comics.

We can't talk about the greatness of Seattle's comics scene without acknowledging the Short Run Comix & Arts Festival. This year's Short Run was the best yet, packed with great cartoonists from all over the world and alive with the kind of crackling energy that used to fill mainstream comics conventions before corporate dullness took over. The fact is, most of these comics were found at Short Run, or they exist because of Short Run. In just a handful of years, it's become pivotal to the scene.

With that said, here are some favorites:

Lots of cartoonists think they're doing something new, but Mita Mahato's debut poetry comics collection In Between is something new. Mahato's paper-cut comics are a whole new vocabulary, evoking slightly different responses in readers than traditional cartooning. The work she's doing here is fascinating and invigorating, but not just because you feel that she's discovering new ground. What's most important is Mahato's poetic voice, which is shy but insistent, like someone who's learned a secret about you and is looking at you with whole new eyes.

The anthology Grab Back Comics was about six months ahead of its time. Earlier this year, before "Harvey Weinstein" became shorthand for "sexual harassment," this comics collection about surviving sexual harassment seemed like a good idea. Now, it seems absolutely essential.

Tatiana Gill's comics are always worth reading, but the strips in Wombgenda, particularly the article about getting birth control at the Country Doctor, feel like a new level in her work. From her body positivity propaganda to her feminist manifestoes, Gill is getting stronger all the time. Her comics are kicking ass in bold new ways.

It's been a couple months and I still can't stop thinking about the bloody climax of Marc Palm's sex-and-violence caper The Fang. Though it stars a Muppet-looking vampire hunter, The Fang is decidedly not for kids. The sex scenes are explicit, the violence is gory, and Palm has a lot to say about why we cover our eyes when the best part is just about to happen.

This year saw Thick as Thieves rise to take the place that the comics newspaper Intruder left in our hearts. In just a year or so, Thieves started as a paper that felt like an Intruder fanzine, but it has expanded and grown to become Intruder's peer. I can't wait to see what next issue brings.

While it's not nearly as brilliant as Peter Bagge's Margaret Sanger biography Woman Rebel, Bagge's biography of Zora Neale Hurston, Fire!!, is about as provocative as they come. Hurston is a great subject for a biography, and Bagge mostly serves her well. But the book can't quite overcome the awkwardness of a middle-aged white man trying to capture the essential spirit of a great Black woman. You might have some problems with Fire!!, but you won't be able to stop thinking about it. This book is a conversation between a writer and her fan, and there's room in this conversation for you.

2017 in review: The Seattle novels that made my year

I don't really have "favorite" books. I read too much, and I read too widely, to believe that any one book can encompass the totality of my tastes and reading experiences. Similarly, I think best-of lists are absolute bullshit. The only reason anyone ever made a list was because they wanted to start a fight. But here we are in the last week of the year, and I do think that some reflection is worthwhile. This week, I'll highlight some of the books by local authors that made my year in reading so memorable. Today, the focus is on novels.

It's been a tough year for me and fiction. The first year of Trump's presidency has stripped my attention span down to a nub. Non-fiction was relatively easy for me to read, but fiction demands attention and suspension of disbelief. Every time I open Twitter, my tolerance for disbelief shrinks a little further.

But these books by local authors reminded me why fiction is so vital. They helped me climb inside someone else's mind, to experience the world through someone else's eyes and ears and nose for a little while. Of all the novels and story collections I've read this year, these are the ones that took up residence in my head.

In a year when The Handmaid's Tale dominated the discourse, Jennie Melamed's Gather the Daughters told a different kind of dystopian story. The collapsed society of Daughters represents the pain and torment of victimized girls — Melamed works with traumatized children in her day job as a nurse practitioner — and as many horrors of sexual abuse have been revealed in the last half of this year, I've thought of this book again and again.

I'm always thankful for Doug Nufer's oulipian novels, which experiment with how much weight language and fiction can bear. This year, he published The Me Theme, and from its first line, the book laid out its particular echolalia: "O pen, open an aesthetic anaesthetic tome to me." It's a book that rhymes with itself multiple times in every sentence, revealing the patterns behind language and forcing the reader to think about words in a whole new way.

It's snide and reductive to say that Tara Atkinson's novella Boyfriends was "Cat People" before "Cat People" was "Cat People," but if that gets you to read the book, I'll say it. Boyfriends is about what it means to be a woman in a society where we still often judge women based on their relationship to men. It's funny and sad and it might make you mad, but you will definitely recognize the woman in this story.

Anca Szilágyi’s Daughters of the Air is a fantastic debut — a magical realist fairy tale set in gritty New York City. It's the kind of book that leaves you utterly confounded at the end, as you try to remember all the twists and turns that you took along the way. It feels like an impossible book, somehow — a product of alchemy, a creation of unearthly talents.

In Laurie Frankel's This Is How It Always Is, a family responds to the needs of their trans daughter with compassion and grace. It's a warm and loving book — a testament to parenting and empathy. In other words, it's exactly the book we need right now.

Talking with Matthew McIntosh about the rhythm of incorporating videos into print books

On Thursday, December 14th, I interviewed author Matthew McIntosh at Elliott Bay Book Company about his remarkable sophomore novel, theMystery.doc. McIntosh is the kind of author who invites the word "reclusive." There are almost no photos of him online, and he has kept himself cloistered away for over a decade working on theMystery.doc. He doesn't take part in group readings, or offer freewheeling chats on Twitter, or have a Facebook page. In fact, the Elliott Bay event was the second of only two readings he did as a part of theMystery.doc's launch.

But McIntosh isn't antisocial or even a little bit chilly, the way you'd expect a so-called reclusive author to be. In fact, he's warm, and charming, and very open about his process. For this event, McIntosh read over a series of videos taken from the book in a 20-minute presentation that incorporated science fiction and spoken word and experimental fiction.

It was a unique performance to celebrate a unique book. theMystery.doc is a behemoth of a thing, a surprisingly readable postmodern novel that is set in the early 2000s but which spans centuries; a realistic book about the dawn of our modern technological age that is stridently, proudly, a book that exults in its page design and corporeality; a big, ambitious book that doesn't have any of the ego or swagger of the typical Big Books by young Franzen wannabes. The book is full of video stills and blank pages and codes and just about every visual trick you can imagine, but it doesn't feel flashy or gimmicky like, say, House of Leaves. Instead, it feels like a book about The Way We Live Right Now. What follows is an excerpt of our onstage conversation.

My ideal version of the book actually turned out to be exactly what the book is. Even when we were doing the ebook — and the ebook by the way, comes free with hardback purchase — when my wife coded this ebook, we were talking about doing that, putting video in there. But that wouldn't really represent what the book is.

So that was a consideration, but I felt like I liked having the time. So much about the images in the book is about time, and so when you come to a scene, or come to a sequence of stills, for instance, there might be stills that will take you 10 to 20 pages to go through.

And so I wanted people to become immersed in the book. I want time to be an issue with them, so that their experience with time, and with that image itself, is part of the experience. I want them to stare at it as long as they want, and never to know what's coming next. If you were to incorporate video, readers would just watch it until it plays out, whereas if you take five stills, you can watch the progression of that time happening.

Video would be passive as well, and that would change the implications of reading and experiencing the book.

Exactly. So, for instance when — towards the end of the book — when the male character turns and runs, he does this in the guise of Jimmy Stewart. It was important in the first page of the sequence to show him sideways, looking and turning and running. The video was so fast that that first moment almost gets lost. So to have it in still form on a page, it’s almost like it’s eternal, in a sense, on that particular spread.

You kind of answered this a little bit, but there were other elements with and the number of blank pages between passages and images, for instance. When people write and draw comic books they worry a lot about the rhythm of the page, and what the reader sees on every page turn and things like that. Was that something you considered?

Absolutely. No question. No question. The design of the book took so long, and was so meticulously done. [My wife and I] had this thing we would call The Turn. And what that meant was on this particular spread, I want the reader to see this particular image. So that means sometimes you have to go back through the design of maybe 20 or 30 pages before it, to make sure that all the text is flowing at that particular rhythm to leave you at that moment where you turn and discover that image.

I wanted to have all of these turns to be surprises. And so every single spread was worked out meticulously — with rhythm, with timing, and with what the reader sees, and what they haven't yet seen.

What was interesting about this project was that every time that we ran up against something that we needed to change — it was never demanded about the text; It was usually running into permissions issues for certain [images] — it turned out better. And so throughout the project I became full of faith that any time I had to do something that was painful because this was the way it was supposed to be, I always had faith that it was going to turn out to be better. And I believe that it did, every time.

Also the book is full color inside, which I'm not sure would have even been technologically possible ten years ago at this scale. Was that a hill you were willing to die on?

Oh, yeah. It was understood. This was going to be in full color, and no edits. Which was a really ridiculous thing to ask. No one would ever do that! Publishing right now is really constrictive — especially with things that are going to cost money, because it's a hard environment to sell literature anyway. And this book costs — I believe it was probably five bucks a copy more than your average book. And yet we only have to sell it for 35 bucks, which is a pretty good deal. And you get a free ebook!

So we thought, ‘well, let's just see if Grove will do it. Grove published my first book without any edits. They were just awesome. And so I asked my agent to go ahead and send it to them, and she did, and when she called back she's like ‘he wants to publish it.’

And I said, ‘that's wonderful. Too bad he's not going to be able to because of the color.’

And she says, ‘he said “Of course we'll publish this in color! Obviously.”'

Every author I've talked to about Grove Atlantic is thrilled with them as a publisher. So I think you you you've got lucky on the first try.

Yes.

There are big books, and then there are there are big books like this that feel like the author just like poured themselves into it entirely. Given the amount of time that it took to produce the book, and how much control you had over it, did you did you feel drained when you were done? Do you have anything anything left in you for a next project?

I hope so. I think it's going to be definitely different. The things that I've been working on now are a lot different. You can only do this kind of thing, once I think. It was such an immersive experience writing it. I basically did nothing else for 12 years — just worked and worked and worked on the book. And that was the only way to do it, I think.

2017 in review: The poetry that made my year

I don't really have "favorite" books. I read too much, and I read too widely, to believe that any one book can encompass the totality of my tastes and reading experiences. Similarly, I think best-of lists are absolute bullshit. The only reason anyone ever made a list was because they wanted to start a fight. But here we are in the last week of the year, and I do think that some reflection is worthwhile. This week, I'll highlight some of the books by local authors that made my year in reading so memorable. Today, the focus is on poetry.

It's been a phenomenal year for poetry in the greater Seattle area. Our poets have responded to the challenges of 2017 with some of the best work we've seen in decades. Some highlights:

EJ Koh's debut collection, A Lesser Love, demands your attention. Love's gaze lands on war and love and history and pop culture; when viewed through Koh's crystalline language, those four huge subjects don't feel like opposites. The whole world makes sense when Koh writes it; even the tragedies have a kind of beautiful sadness to them. It's as confident a debut as you'll read, and that confidence is entirely earned.

Robert Lashley's second collection, Up South, takes the fury and the contemporary language of his debut and places it into the classical tradition. This is a book that looks back at the thousands of years of poetry that came before and proudly builds upon it. Lashley is on his way to being one of the Northwest's greatest poets, and Up South is a giant step in his ascension.

Halie Theoharides, the author of Final Rose, is not from Seattle. But the book was published by Seattle press Mount Analogue, and it seems doubtful that any other city could have produced this book. It's a beautiful tone poem built entirely out of screen shots of the reality TV show The Bachelor, and it's as funny as it is profane. Only a publisher as young and brash as Mount Analogue could have recognized the beauty in this project, and then brought the book to bookstores without compromise or commercial compromises.

When Seattle poet Joan Swift died, many of us who mourned were consoled by the fact that she had one more book to give us. That book, The Body That Follows Us, was published this year. And it is a portrait of the artist as an old poet. Swift faced her body's inevitable decline with humor and a very observant eye. As her last gift to us, Body is a tremendous document, charting a little-recorded time in an author's career: old age and infirmity. Swift acknowledged the brittleness of her bones, but she also acknowledged that those bones are what will outlast her.

Maged Zaher hopefully has many years of poetry ahead of him, so it seems weird that he's already published a collected edition of all his published work to date. But Opting Out is exactly the kind of career retrospective that he needs. Zaher has been fairly prolific, and there's enough work in Opting Out to chart his trajectory as an artist: from a funny, horny poet to a revolutionary who — some things never change — thinks about sex a whole lot.