Portrait Gallery: Seattle Food

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday, November 15: The Food and Drink of Seattle Reading

Judith Dern’s new book digs into the history of Seattle’s food, from mushrooms to salmon. All the usual favorites, from geoducks to craft beers, are represented in the book.

Third Place Books Ravenna, 6504 20th Ave NE, 525-2347 http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Criminal Fiction: No turkeys here

Every month, Daneet Steffens uncovers the latest goings on in mystery, suspense, and crime fiction. See previous columns on the Criminal Fiction archive page

Reading around: new titles on the crime fiction scene

A mother who recently disappeared; a suddenly-missing wife; and “a new friend named Lizbeth”: these are the titular women of Jeff Abbott’s Three Beths (Grand Central), a psychological thriller primarily driven by Mariah Dunning’s search for her vanished mother, Beth. When the police try to coax her away from her private investigation, Mariah redoubles her efforts, aided in certain – and uncertain – ways by an ambitious true-crime blogger and wanna-be podcaster, as well as by several friends and relatives of Bethany, the missing wife. Like all best puzzles, this one grows richer the deeper Mariah delves. An ineluctably terrifying but highly-rewarding read.

In Lisa Unger’s Under My Skin (Park Row Books) photographer-turned-agency-director Poppy Lang is mired in a nightmare: her husband, Jack, was murdered while out on a run. In the ensuing year, Poppy has been a slave to sleep-deprivation and tauntingly-missing memories; she’s also been popping pills like there’s no tomorrow. As her friends and family try to cocoon her from pursuing too many unanswered questions, Poppy wades her way through daily life in a kind of waking dream, unwilling to abandon her questions. But the danger threatening what’s left of her world is all too close and present, an ugly reality just waiting to invade. In a novel steeped in the world of photography as well as both canny and uncanny observations, Susan Sontag’s On Photography is included in the author’s Acknowledgements, and, within the story, there’s a gentle nod to George Pitts, the prolific and inspiring photographer, photo director, editor, painter, writer, and teacher.

Chicago’s VI Warshawski is on top form in Sara Paretsky’s Shell Game (William Morrow). A missing niece and deep trouble for a friend’s nephew mean that Victoria Iphigenia has two mysteries to juggle, and finds herself up against more life-threatening moments than she can count on one hand. While she’d rather be watching reruns of Kojak, Paretsky’s peerless PI comes up against some of the more toxic sides of humanity, including the arrogance of the elite, the inherent invisibility assigned to service workers, and the horrific brutality of America’s current policies: “We had become a nation of bullies.” But there’s hope here too, generated by the infallible love between a father and daughter, and through Warshawski’s own father’s words ringing cautiously, optimistically, in her ear: “Measure twice, cut once….It’s advice for life, Pepperpot.”

Armand Gamache, currently on suspension from the Sûreté du Québec, finds himself one of three executors of the will of a woman whose name is a mystery to him, until that particular mystery is resolved over a robust community-centered conversation in his bucolic village of Three Pines. But from small puzzles do large, ever-more excellent ones grow, especially in a Louise Penny novel: in Kingdom of the Blind (Minotaur), as Gamache does what he can to prevent a destructive amount of toxic opioid flooding the streets of Montreal, he and his colleagues chase up murder most foul, dark doings at high-class financial institutions, and an extended legal matter that puts Bleak House’s Jarndyce v Jarndyce to shame.

The Quintessential Interview: Lou Berney

Set against the already-tense days following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Lou Berney’s November Road (William Morrow) takes you on a searing and soul-chilling road-trip during which two disparate lives collide in a landscape populated by dark-hearted hit men, mob heads, and an emerging-from-his-shell teenager. There are incisive inclusions of Bob Dylan lyrics, and inescapably funny moments: “She needed a kind face, an encouraging word. Instead she found a sour Baptist pickle behind the motel reception desk.” Depicting the depths of a dark chapter of American history, this beautiful novel nonetheless offers promising elements of light as a rogue fixer falls for companionship, and a stifled suburban housewife finds her power, her voice, and herself.

What or who are your top five writing inspirations?

Chilly, rainy weather always gets me going. Reading a great novel will often temporarily crush my spirit but then a few hours later I’ll be all jacked up to hit the laptop. Driving through my hometown of Oklahoma City, watching an amazing sunset split open the sky – that’s when good ideas often come to me.

Top five places to write?

A coffee shop in Oklahoma City called Cuppies & Joe (it’s in a great creaky old house); my kitchen table; my back deck while my dog futilely but enthusiastically chases squirrels; airplanes and hotel lobbies (lately, while on book tour).

Top five favorite authors?

Five? Are you sure I can’t give you five hundred? Since I have to narrow it down, I’ll stick to contemporary novelists and say that five OF my favorites are Kate Atkinson, Don Winslow, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Attica Locke, and Rachel Kushner.

Top five tunes to write to?

Rosanne Cash’s version of “Long Black Veil.” “Sweet Jane,” by the Velvet Underground. “Somebody Have Mercy,” by Sam Cooke. Anything by Jenny Lewis. If I’m in a really bad spot, I’ll crank Social Distortion’s “Ball and Chain."

Top five hometown spots?

Chesapeake Arena during an Oklahoma City Thunder basketball game. One of the great indie bookstores in Oklahoma City (Full Circle, Commonplace, Best of Books). Memorial Park by the old fountain that’s been there forever (and was in a Flaming Lips video). Any pho restaurant in the Asian district. The garden behind the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum where legendary rodeo bulls and bucking broncos are buried.

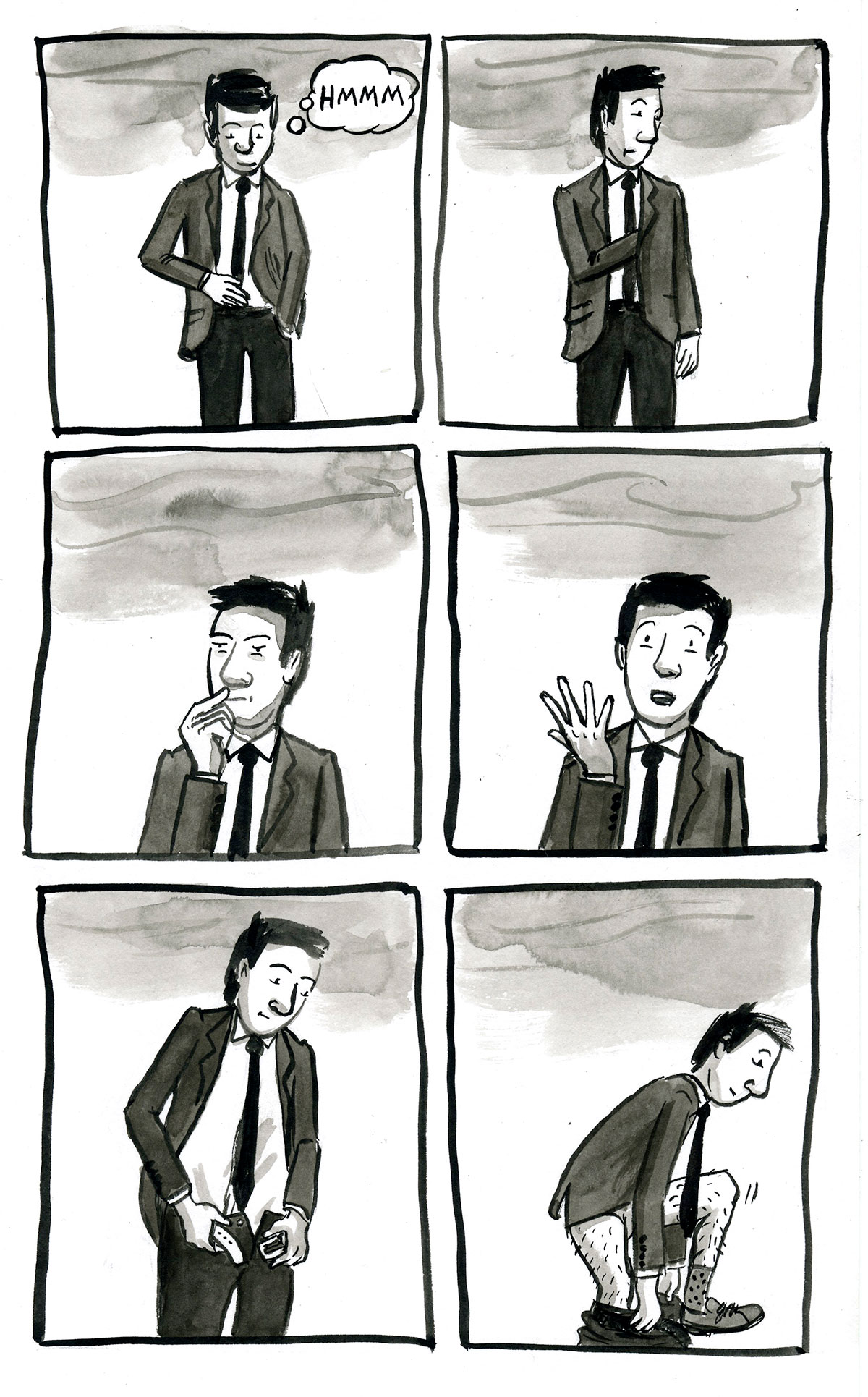

Thursday Comics Hangover: A dress unknown

I'm still making my way through the mammoth stack of Short Run books I bought earlier this month. It's not a chore at all — I love reading minicomics — but it's rare when a book stands up and demands my attention.

One of the attention-grabbiest comics in this year's Short Run haul for me is Liz Prince's memoir Tomboy. This is a memoir about Prince's lifelong struggle with gender conformity, focusing mainly on her school years.

"I DON'T LIKE ANY DRESS," Prince yells as a toddler in the beginning of Tomboy. "I HATE THEM!" Those who believe that gender is a hard and fast rule would do well to read about Prince's instinctual revulsion against any item of clothing that could be considered girly. This is not a choice; it's how she was born.

And Tomboy isn't all about clothes. It's about how Prince learned to accept herself, and how she was not always accepted by her peers. Prince is a charming and accessible narrator, and her art is clean and accessible — kind of a perfect cross between John Porcellino and Julia Wertz.

As Prince ages over the course of the book, her challenges become more and more complex. The gender norms of high school begin to crush her spirit. She doubts her own resolve. But Prince's understanding of herself also deepens, and that understanding gives her the strength to be true to her own calling.

Tomboy is funny and sweet and deeply reflective. It's the kind of book that will sing directly into someone's ear. It will inspire a shock of recognition in some tomboys, and it will help more than a few readers come to the realization that not everyone feels comfortable dressing like a generic gendered figure sign on a bathroom door. It's such a personal document that everyone has something to learn from it.

Condomnauts is the Cuban Kilgore Trout novel you never knew you needed

I don't think I've ever read Cuban sci-fi before, so I don't have much of a comparison available for Yoss's novel Condomnauts. Is it odd for Cuban sci-fi? On par? Do most Cuban sci-fi writers go by one name, like Yoss? Is Cuban sci-fi generally this horny?

So I hope you'll forgive my provincialism if I compare Condomnauts to an American author. It reminds me of nothing so much as Kurt Vonnegut — or, more accurately, Kurt Vonnegut's sci-fi novelist character Kilgore Trout. Condomnauts imagines a far-flung future in which astronauts from Earth traverse the galaxy as part of an intergalactic community. Our main character, Josué Valdés, specializes in making First Contact with alien species he encounters, and in this future every First Contact is performed through a sex act.

There's obviously no rule against using nonbiological protective barriers; sometimes you have no choice but to turn tot hem, such as when your oxygen-based body has to get together with a fluorine-based life form. But aside form such extreme cases, anything as crude as a physical barrier or filter such as a condom is generally considered an unpleasant discourtesy, as well as evidence of the udnerdeveloped medical sciences in the culture whose representatives resort to such crude measures.

That's basically the whole plot of Condomnauts: Valdés, who is famous for fucking alien species in the name of free interstellar trade, is trying to fuck a new alien species before other condomnauts. It's basically a pornier Star Trek.

I enjoyed Condomnauts a great deal. (I'm sure that David Frye's translation is a big reason why the book flew past in a flash.) There's a bit too much exposition in the book's middle, but the main character is interesting enough and the premise is so wild that even while meandering it keeps a reader's attention.

Those expecting Condomnauts to read as propaganda for some scary isolated communist regime will be sorely disappointed. The book is fun and well-versed in sci-fi history, including a good Asimov joke partway through. I don't know if Condomnauts taught me anything about Cuba, but it entertained me as a classic sci-fi novel with a porny modern twist. Sometimes, that's all we need to ask of our literature.

Does book reviewing have a future?

Earlier this fall, I interviewed book critic and author David Ulin at Elliott Bay Book Compahy about his exceptional book The Lost Art of Reading: Books and Resistance in a Troubled Time. We talked about a wide range of subjects, including how we reacted as readers to the election of Donald Trump and whether anyone has written a truly good post-Trump novel. But this excerpt of the discussion, about the future of book reviewing, is particularly relevant to the interests of Seattle Review of Books readers.

Since you have a long and storied history in the field, what do you think is the state of a book reviewing in 2018? Does book reviewing have a future?

Has book reviewing ever had a future?

[Laughs.] Does book reviewing have a past?

I used to joke around when I was doing it for a full-time living that I had unerringly found the lowest-paying, lowest prestige corner of publishing. I had just gravitated right to that, and I was someone who actually — perversely — supported my family as a freelance book reviewer for a long time.

"Supported." I use that word very loosely. When I was freelancing I was reviewing ten or 12 reviews a month because that was my main bread-and-butter gig.

There's two aspects to it, right? With the art of book reviewing, you know that nothing has changed as an abstract. Certainly where it's available and how much it's available has changed. But the inquiry, the essayistic practice and engagement of the writer with a material? I think none of that has necessarily changed.

I think actually in some ways book reviewing or book culture is as robust as it's been in a long time because of the variety of, of web venues that have stepped up. It's impossible to make a living, which is a big problem — the web venues don't pay, or don't pay comparably to the print venues. And the print venues never paid that well to begin with. But I do think there's a lot of places for literary conversation to take place — maybe more places, and certainly more diverse places, than there were ten or 15 or 20 years ago.

I go back and forth on this: I don't miss the gatekeeper model particularly, although I do kind of like the authority of critics. But I think that that authority has to be earned by the critic — not by virtue of who the critic is writing for, but by virtue of what the critic is putting on the page. And so I think if anything has happened is there's more of an onus on the critics to establish their own authority, as opposed to relying on the authority of the institution that they work for.

I think we're clearly getting on about midnight, at this point, for the book review section. But I'm interested as a reader and as a writer in the proliferation of other non-book-review-section-type venues where the conversation can take place.

Accidentally honest

Published November 13, 2018, at 11:56am

Even the most honest memoir has the lie of a narrative imposed upon it. What happens when a memoirist refuses to play nice with an imposed narrative?

Centaur Culture

On the last day of the working week we stopped at the video rental store. It was right next to the Mar T Café; the second brightest storefront in my hometown. Movie titles bobbled inside their plastic sleeves. The pebbly brown clamshell cases imbued the store with a gently chemical tang. If you didn’t have a VCR, you had to ring a bell in the back and ask to rent one. I always carried it out to the car reverently, palms up and back straight.

In The Neverending Story, Atreyu’s horse Artax sinks. I watched that scene in tense, sweet agony on Friday nights. Atreyu cajoled his horse to fight the quicksand then turned panicky. The horse, an elegant dappled gray, peered winsomely up at Atreyu and then bellied into the mud. The movie’s pitchy black swamp was full of bleak, foliage-stripped trees; my childhood home was a decades-long construction site. Sitting on subfloor in front of the TV, the sludge of Cascadia mud licked at my nostrils from the unfinished windows. The soundtrack’s uncanny chorus of mire-murmur was so like my rural bedtime lullaby, I thought the narrative was swallowing me.

I had my first pony at three. By eight, I was breaking gentler mares and geldings to saddle. Atreyu was a warrior from the Grassy Plains. He was the figment of a German author’s infatuation with indigeneity. I went ahead and assumed he was Shawnee. For a very long time, I thought Atreyu was a girl. I thought she was Shawnee and maybe we were cousins somewhere down the line. I thought I could be them, so I imagined reaching up for that VHS tape every Friday was a ceremony.

Once I read that Shawnee scouts taught fur traders how to evade quicksand by staying utterly still. All that movement I assessed on the screen, Atreyu’s overt show of dismay, consigned that swift, slim horse to the mud. Hush, I remember whispering at the screen. Shut up and be still. Someone I loved best got drunk and babbled tell me about your favorite problematic movie. I would never do what you did. Look at your fingers, he said, they are actually blue. Unwrap your hands from all that before you are pulled under.

Read a chapter from No Good Deed, courtesy of sponsor Rosemary Reeve

"This book feels ripped from today's headlines," says Reeve, "but I wrote it more than 20 years ago. In No Good Deed, I was trying to create a scenario that would be everyone's worst nightmare. More than 20 years later, it still is."

Stop by our sponsor feature page for a sample.

I wish to hell I had made Mark stay over that night. I could tell how tired he was. His face looked taut and pale in the misty evening, like a grey mask. Even inside the house, his eyes seemed shadowed. More ...

Sponsors like Rosemary Reeve make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you can sponsor us, too? We're sold out through January 2019. And even though we haven't released the next block, there are just a few dates left in February. Want to reserve your dates before they go public? Just send us a note at sponsor@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from November 12th - November 18th

Monday, November 12: Evolution Reading

Eileen Myles is one of the mightiest writers in America today. Their new collection of poetry, Evolution is about America and the presidency and corporate consumer culture. This might just be the poetry collection that 2018 needs. Hugo House, 1634 11th Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, November 13: SFWA Reading

The Science Fiction Writers of America celebrates its Northwest chapter with readings from two local sci-fi greats: Sandra Odell and Mary Robinette Kowal. Kirkland doesn't see very many readings, so it's good to see the SFWA representing on the east side. Wilde Rover Irish Pub & Restaurant, 111 Central Way, Kirkland, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free, 21+.Wednesday, November 14: Fierce Reading

Jo Weldon is Headmistress at the New York School of Burlesque. Her new book Fierce is subtitled The History of Leopard Print. It's about the daringest print that looks great on everyone, and how it quietly took over the fashion world. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Thursday, November 15: The Food and Drink of Seattle Reading

Judith Dern's new book digs into the history of Seattle's food, from mushrooms to salmon. All the usual favorites, from geoducks to craft beers, are represented in the book. Third Place Books Ravenna, 6504 20th Ave NE, 525-2347 http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Friday, November 16: Catch, Release Reading

Port Townsend writer Adrienne Harun celebrates her recently published second collection of short fiction tonight. It's about thefts and cults and con games and violations of trust.Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Saturday, November 17: The Sexiest Man Alive Book Launch

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, https://www.facebook.com/events/299333797329025/, 7 pm, $5.Sunday, November 18: Seattle Anarchist Bookfair

Come check out tables from vendors including Ad Astra Comix, Rose City Antifa, Left Bank Books, Tech Workers Coalition, Detritus Books, and Blood Fruit Library at the annual Anarchist Bookfair. Workshops include a report of recent IWW actions and a discussion of racism.Vera Project, 305 Harrison St, 956-8372, http://seattleanarchistbookfair.net, 10 am, free.

Multiple outlets are reporting that Stan Lee, the editor and writer who guided the Marvel Universe from a scrappy small comics publisher to one of the worlds' leading entertainment brands, has died. He was 95 years old.

You will see an uncountable number of tributes to Lee over the next few days, months, and years. It's true that Lee shaped the direction of American popular culture in a way that few others have — Walt Disney is the only other name that immediately comes to mind. But the truth is more interesting and more complicated than just a Horatio Alger story about a writer with a dream. Seattle's own Fantagraphics famously published an entire issue of their magazine in 1995 The Comics Journal devoted to Lee's complicated relationship with artists at Marvel.

But there will be plenty of time to tease out the tangled questions of ownership and creator rights that Lee leaves behind. For now, I prefer to reflect on the fact that Lee was once an aspiring novelist named Stanley Lieber who purposefully created the Lee persona so he could save his real name for a Great American Novel that he would never write. But now, looking back on his career, very few writers in the history of the world can claim the kind of successes that Lee enjoyed: he's changed the world in a very real, very palpable way, and his passing will be mourned by millions.

Literary Event of the Week: Sexiest Man Alive reading at Vermillion

You might know Amber Nelson from her amazing (and sadly now defunct) press Alice Blue. Or perhaps you just see her in the audience at all the best readings in Seattle. Nelson is what we call a Stellar Literary Citizen: she shows up, she contributes, and she promotes the work she likes.

This Saturday, Nelson will debut her second collection of poetry. It's titled The Sexiest Man Alive, and it's inspired by People magazine's annual feature. (This year, People selected Idris Elba as the Sexiest Man Alive, which is a rare case of the magazine getting things exactly right.) It's a book about gender and fantasy and what it means to be sexy, but not in a tawdry way.

This party looks to be a big damn deal, with a DJ and a dance party and a performance from some of Seattle's best drag kings, who will be appearing as some of People's previous Sexiest Men Alive. Performers include starrswagg, who performs hip hop at drag king shows around town.

With Thanksgiving fast approaching, this week is the last full week of readings we'll see in Seattle until after the holidays. That means this party is one of the last big literary blowouts we'll see in 2018. And it's a pretty great book to bow out on: Nelson's poetry is smart and humane and thoughtful and very, very good. We could use more work like this in the coming year.

Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, https://www.facebook.com/events/299333797329025/, 7 pm, $5.

The Sunday Post for November 11, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Hammerhead

Seattle Review of Books co-founder Martin McClellan heard Jennie Shortridge read “Hammerhead” at Lit Crawl in October — yet more evidence of how necessary the event is for getting ears and eyes on incredible new work. Shortridge writes the story of multiple assaults her mother endured, at a time when women had little if any hope of help if they told what had happened. Like Martin, I fell in love with this essay — with its anger, with its honesty, with how it’s a daughter’s chance to speak up for a mother who couldn’t.

When we were kids, our mother spoke of him with reverence, and treasured that horse and bowl until her early death in 1990 at the age of 57. The horse lives on in my sister's house, the bowl in mine. Why, I wonder now, imagining throwing it in a dumpster, maybe giving it a few good hard bangs first. But she loved these things. She made us love them, too, these pinpoints of light from her girlhood. Do we honor her or him by keeping them? If we throw them away, what do we trash, and whom?

What I Learned About Being Nonbinary Through Documenting a Year of My Life

If you’ve ever found a strip of someone else’s photobooth snapshots, you know how uncannily intimate they can be. There’s no background, no context, just a stranger’s face and what it tells you, intentionally or not. The message isn’t for you — but it’s so very, very close.

Every month for a year, H. Nicole Martin made a pilgrimage to Seattle’s photobooths so they could look back at their face and see what it said. Over the same year, Martin came out publicly as nonbinary and queer, fell apart, fell in love. This piece captures that experience, mixing images and precise, personal prose to ask what’s revealed, what’s betrayed, and what we learn about ourselves by telling our own stories.

I don't know any of this that first day in December, as I buy a pastry stuffed with taro and walk around the market slick with gray sky. I only know the three seconds between each click of the camera, the faces I make, the ways I hope the image communicates my identity to the world: beautiful, enticing, what I believe to be a woman, the woman I have believed to be myself. In the third frame, I am smirking and think of it as a tiny omen; what for, I am not sure. I begin the project because I have a sense it will be important, though I cannot fathom why.

The Menace of Eco-Fascism

Is nothing sacred? Can we not hug trees, at least, without tripping over Richard Spencer? Apparently not. For some people, “make America great again” is starting to map to an environmental nationalism that protects public lands for the enjoyment and exploitation of a privileged few (yeah, it’s the same few, and the same privilege). Matthew Phelan has the story, with a lot less snark and many more facts.

(Seriously, though, this is good to know about and understand — some coalitions aren’t worth building. Cuddle up to trees, but not to Nazis, please.)

This romantic-reactionary tendency in environmentalism has fertile ground in US Green Party coalitions, if only because many pragmatic environmentalists have self-selected out of these marginalized third-party engagements. Concerted efforts by anti-Semitic authors David Pidcock, Michele Renouf, and Matthias Chang to insinuate their ideas into the Green Party's defense of Palestinians, and its critique of international finance, plagued the campaign of Green Party presidential candidate Cynthia McKinney in 2008, and this example is not unique. In general, what has been left is an activist community that, while far from being a full-fledged "green–brown" alliance, is dangerously susceptible to eco-nationalist positions and premeditated infiltration by like-minds from the far right.

Fascism is Not an Idea to Be Debated, It's a Set of Actions to Fight

Aleksandar Hemon explains why refusing to provide fascism with a public platform is not an issue of free speech, but of survival.

. . . only those safe from fascism and its practices are likely to think that there might be a benefit in exchanging ideas with fascists. What for such a privileged group is a matter of a potentially productive difference in opinion is, for many of us, a matter of basic survival. The essential quality of fascism (and its attendant racism) is that it kills people and destroys their lives — and it does so because it openly aims so.

‘It's not fair, not right': how America treats its black farmers

This is a great investigative piece by Debbie Weingarten on systemic, systematic, and devastating discrimination against black sugarcane farmers in the United States. It’s the sort of claim that people who benefit from the entrenched system find easy to dismiss — so careful, fact-based reporting is needed. Weingarten’s piece is compelling, and enraging.

US census of agriculture statistics show a 44.7% decrease in black farm operators in Iberia parish — where the Provosts live — between 2007 and 2012, compared with a 12.3% decrease in white farm operators. In neighboring Vermillion parish, where June farmed the majority of his sugarcane, black farm operators decreased by 17% between 2002 and 2012, while white farmers increased by 6%. Nationally, less than 2% of farmers are black.

June says there were approximately 60 black sugarcane farmers in the area in 1983. He keeps their names neatly printed, line after line, in a notebook.

By 2000, that number had dwindled to 17. Today, June and Angie count only four.

Whatcha Reading, Lesley Hazleton?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Lesley Hazleton is a Seattle-based, British-born writer, journalist, and self-described "accidental theologian." Her latest book, Agnostic, A Spirited Manifesto, caused Paul Constant to do "something I have not done in a very long time: I flipped the book over, opened it, and then read the whole thing over again immediately". She'll be appearing next Thursday, the 15th, in conversation with Michael Hebb at the Elliott Bay Book Company.

What are you reading now?

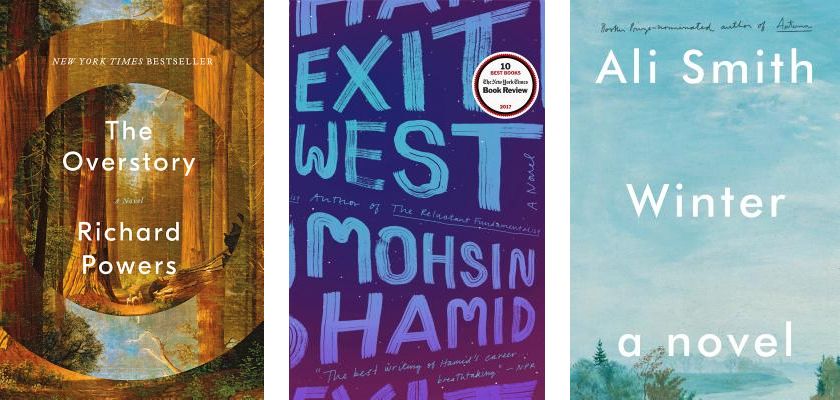

I was downtown on Vine Street recently, one of those blocks planted with puny urban specimens that will never be allowed to grow into full treedom. One had been cut down — diseased, I guess — and on the stump, a single word had been painted in white upper-case letters: BROKE. “Yes," I thought, "somebody else has read The Overstory.” For once, Richard Powers is not showing off how damn clever he is, maybe because he really cares about trees — and humans — and how they communicate (trees with trees, humans with trees, humans with humans). It's moved me to tears at times, and am already buying extra copies for friends. I’ll shelve it alongside Alan Weisman's The World Without Us.

What did you read last?

Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West. The third time I’ve read it — and I suspect not the last. I enjoyed the delicious mischief of The Reluctant Fundamentalist, but felt no need to read it again. This time, Hamid has dropped the irony, not least because the refugee crisis is way beyond that. In the kind of spare, pared-down prose that induces writer’s envy in me — hate to say it, but the word really is ‘crystalline’ — he pulls off a magic trick, making reality all the more tangible by inserting a deft touch of the surreal. And I don’t even need to buy copies for friends, because they’re already reading it.

What are you reading next?

Given the time of year, I'm ready for Ali Smith’s Winter. Because How To Be Both. And Artful. And There But For The. And anything she cares to write.

The Help Desk: Literary theft on Instagram

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

So my best friend just got, like, a gazillion follows on Instagram by all these celebs and start-of-alphabet listers after she posed sultry librarian pics WITH MY DANG LIBRARY!!!!!!

She won't even tag me or anything, so I'm having tons of FOMO about her living big on my taste, and all these people are like "we like the same books!" and she doesn't even read.

How can I get back at her?

Wendy, West Seattle

Dear Wendy,

Your friend sounds needy, and not in a cute trying-to-bribe-nurses-at-George-Washington-University-Hospital-to-give-RBG-stem-cell-jello-shots-because-sweet-tap-dancing-Jesus-all-20-pounds-of-that-85-year-old-woman-must-stay-fit-and-healthy-and-strong-for-another-two-years-at-least kind of way. Your friend sounds needy in the traditional, boring way: she is a praise hound.

You cannot stop a praise hound from panting and baying for praise any more than you can stop birds from trying to have sex with bees, or RBG's flappy little limbs from slowly calcifying right before our horrified eyes.

Here is what you can do: invite your friend over for another library photo shoot – perhaps offer to snap some pics of her in a festive sweater for a holiday card, since the Instagram post was so popular. Before she arrives, go to a used book shop and add some fun alt-right Easter eggs to your shelves like "The America We Deserve" and "Time to Get Tough" by Donald Trump, "Contemporary Voices of White Nationalism in America," "Truth, Justice, and a Nice, White Country," maybe something cheap and smutty by Ann Coulter, and perhaps a copy of "Mein Kampf". If she's not a reader, she won't bother looking at your shelves because to her, books are merely a platter on which praise is heaped.

Or, if you don't want your friend to be accused of sympathizing with the alt-right movement, you could just comment on her Instagram post, something along the lines of "Yes, I'm dying to know what your favorite book from my library is."

Either way, be playful! Have fun with it! And pray and/or offer up a blood sacrifice for RBG.

Kisses,

Cienna

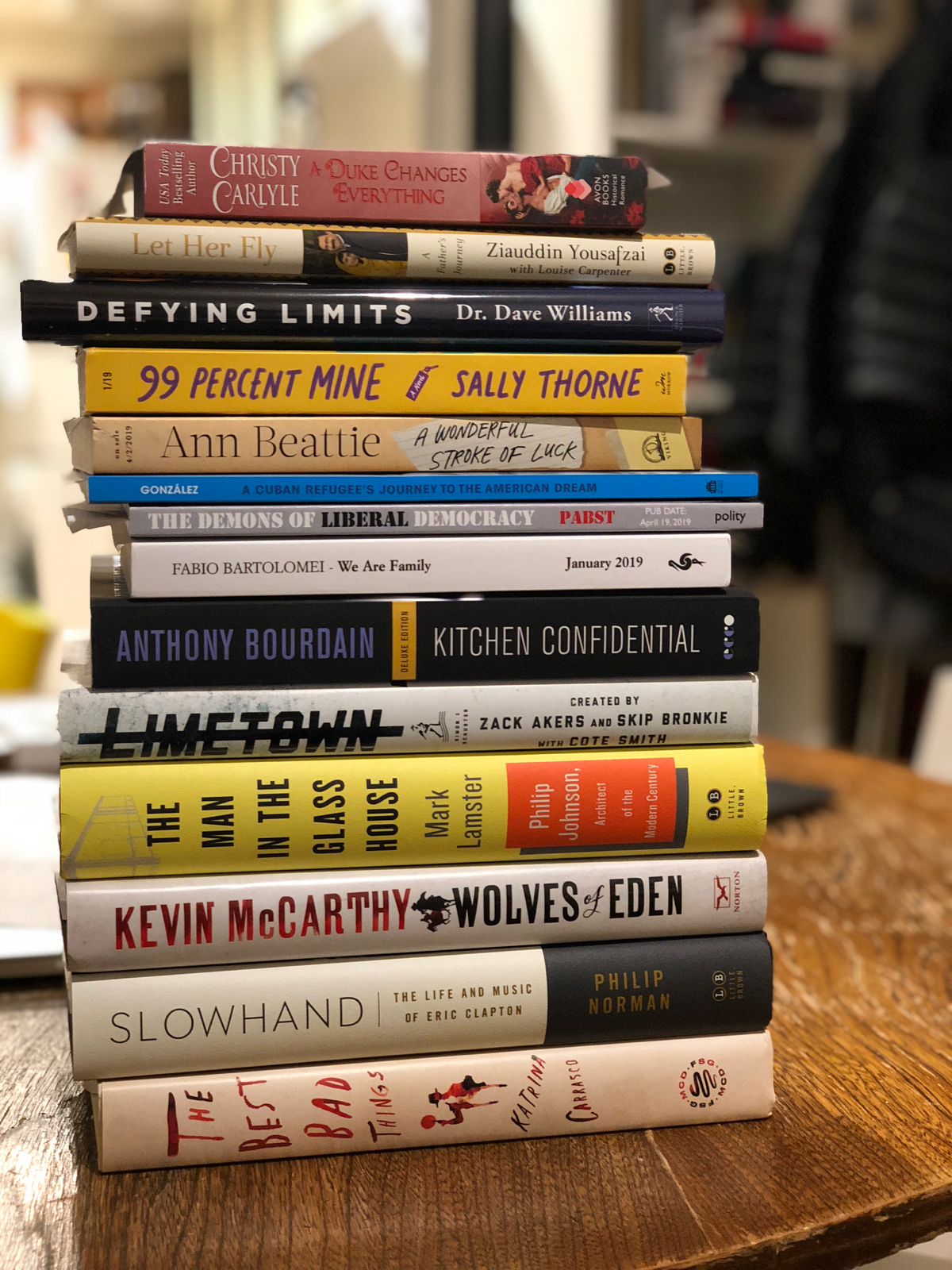

Mail Call for November 9, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Portrait Gallery: Timothy Egan

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Timothy Egan

Happy Birthday to Seattle author and journalist Timothy Egan, whose non-fiction books about America and the Pacific Northwest have expanded our understanding of the people who inhabit this place.

Future Alternative Past: Vegetable love

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

We’re mammals. Beasts. But when we look at the world we inhabit, we see ourselves surrounded by plant life, and when we look at that world through the lens of SFFH we can see the plants surrounding us as neighbors and potential rivals.

Fantasy is full of dryads, mythological tree spirits I first became acquainted with via CS Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. Though Lewis’s series is famously a Christian allegory, clues to the books’ religious core escaped me, and this may be due to my fascination with its pagan façade. Narnian dryads died when their trees were chopped down, and I developed a fierce protectiveness for the saplings in the vacant lot next to my childhood home.

But did they need my protection? Sneaking under the fence to watch movies at the drive-in on the far side of the ballpark across the street, I was introduced to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short horror story “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” This 19th century tale of a toxic garden centers on a luridly beautiful tree bearing fatal flowers. Its breath is death — except to the young woman who tends it, who is in some way its sister. The woman’s exhalations bring death, too, to those who come too close. Her touch could kill the student who courts her, instantly; thorns and poisons are plants’ primary defenses, and far more potent than the wrath of a grade-school girl.

Science fictional instances of botanic speculation include several wistful references to human photosynthesis. There’s 2011’s By Light Alone, by Adam Roberts, with its ironic take on conspicuous oral consumption; earlier, there are the symbs of John Varley’s Eight Worlds series, symbiotic human/plant partnerships that allow us to live indefinitely in the vacuum of space — as long as said vacuum is sunlit. Ursula K Le Guin often celebrated our interrelatedness, most notably in her 1972 novel The Word for World Is Forest. In my short story “Slippernet” I invoke the power of forests’ mycorrhizal networks or “Wood Wide Web” as empathy-injectors disabling Trumpian othering, and I’ll be doing more with these fungal threads in my upcoming sequel to Everfair.

But by far the most interesting sfnal exploration of straight up plant intelligence is Sue Burke’s novel Semiosis. Set onan extrasolar colony, the book begins with a wincingly plausible cascade of mini-disasters culminating in a tense situation which only partnership with an herb-based sentience can resolve. Kim Stanley Robinson’s Aurora highlights the futility of classifying extraterrestrial life along an Earth-context plant-animal binary, which even locally falls apart (slime molds, anyone?). And yet, drawing on recent scientific discoveries, Burke does a tremendous job of showing us the thought processes of an actual vegetable. In doing this she moves a step beyond the scope of Le Guin’s 1971 short story “Vaster than Empires and More Slow,” writing some passages from the viewpoint of her alien character’s widely distributed and practically immortal mind.

Recent books recently read

My Writing the Other co-author Cynthia Ward’s latest pulptastic vampire novella, The Adventure of the Dux Bellorum (Aqueduct Press), pits Dracula’s queer daughter against a mad scientist in Kaiser Wilhelm’s pay. The daughter, Lucy Harker, is a British spy assigned to keep the titular “dux bellorum” — aka “warlord” — Lieutenant-Colonel Winston Churchill out of trouble during his tour of duty on the Great War’s Western Front. Since that includes battling mind-controlled wolfmen and giant telepathic pterodactyls, this is a pretty tall order. Fortunately Harker’s lover, another lesbian vampire, happens to be a British spy as well. Together the couple fight the good gonzo fight for Truth, Justice, and the Triumph of Democracy. Throughout their sensationalistic escapades Ward references the works of HG Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, MR James, and other forefathers of SFFH with wholehearted enthusiasm, yet still manages to update their stodginess with breathtakingly matter-of-course feminism and homophilia. Which is to say this is nostalgia for forward-looking readers. A neat trick. Also a fun one.

Swedish author John Lindqvist’s debut novel Let the Right One In caused an international stir, blending traditional vampire lore with modern social issues such as bullying and gender fluidity. I Am Behind You is the English translation of Himmelstrand, a later and decidedly weirder work of Lindqvist’s, a novel which only hints as to what befalls its characters. Explanations are apparently being left for the two following volumes of this trilogy; what we have in the first book is the set-up, plus a bit of nasty description and some character development.

The set-up: four RVs are mysteriously transported with their contents and inhabitants to a strange, grassy field beneath a sunless blue sky. The viewpoint characters include two kids, four couples, and a beagle. Most of the nastiness boils down to an attacking horde of whimpering zombies and a powerfully acid rainfall, though there’s also plenty of old fashioned gore: spilled blood, oozing guts...the proper balance of ick and wtf, in sum, to begin a long and hopefully disturbing new saga of loneliness and horror.

Couple of upcoming cons

Con+Alt+Delete is an anime convention you’ll want to attend if you like “Full metal Alchemist, Dragon Ball Z, Yu-Gi-Oh, Lolita Fashion, Homestuck, My Little Pony,” and similar sorts of entertainment. Or maybe you ought to go if you want to get your cosplay on — there will be competitions.

For those who prefer something a bit more specialized there’s Tacoma’s Weekend of Wizardry, which basically promises live-action Harry Potter fanfic. It sounds especially tempting to those of us still awaiting the arrivals of our owls.

This is very sad news from the best general-interest arts publication in the city:

We hoped this day would never come. City Arts as we know it has reached its end. We’ve run out of funding and are ceasing publication.

We know this will likely come as a shock and a loss to many of you, as it has for us, so before we sign off we want to share how we got to this point and reflect on the journey.

Go read the rest on City Arts. The magazine hopes to continue in the form of "a smaller all-digital platform," but as of today the entire staff has been let go. This is a very sad day in Seattle media history, and we'll be covering this story in weeks to come.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Shedding some light on the subject

Maybe I'm jaded, but I don't see much in comics that strikes me as especially new anymore. It's not so much that it's all been done, it's just that very few people are still trying to push the medium forward in exciting ways. Who is experimenting with the medium and form of comics? Who is trying to break comics out of normalcy?

The first name that comes to mind when conjuring a list of comics experimenters is Seattle cartoonist Eroyn Franklin. I've previously called Franklin one of the greatest mad scientists working in comics today, and I just encountered one of her older works that strikes me as one of her boldest and most inventive works.

At Short Run last weekend, while visiting Franklin's booth, I asked about a book called A New Home. She demurred slightly, saying it was an old book and that she was working on a newer version. I bought the book anyway, and holy cow am I glad I did.

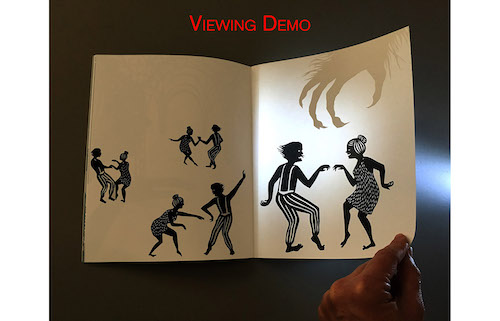

On the face of it, A New Home might sound like a gimmick. Here's the deal: the book is made up of silhouettes and splashes of color. It doesn't have panels; it's laid out like more of a picture book. So you look at a page, which has large, clear images and a few words. One page, for example, has the outline of a monster with its head reared back. The monster is white; the background is black. The words "And down, down, down she went" are in the upper right corner. It's a striking, minimalist image.

Franklin colored the reverse side of this page a deep, bloody red, and she drew a figure tumbling into a pit. So when you hold the page up to a strong light, a new dimension reveals itself: the inside of the monster turns red, and we can see it swallowing a woman. Every page of the book has a hidden secret that reveals itself when you hold the page up to light.

Comics are a dance between words and pictures. But with A New Home, Franklin adds a new partner to the dance: words and pictures interact, and then they interact again with the pictures on the other side of the page, creating a lively third dimension that lives in a realm that's perpendicular to the comics page.

A New Home is a simple story about a woman who goes exploring and faces grave danger. But the way each page reveals its secrets creates a new tension to the fable Franklin tells. Sometimes the secrets are gory. Sometimes they're pleasant. Sometimes they change the way the reader feels about the story.

Franklin is always moving and trying to discover new ways to tell stories through comics. But I hope she'll take a while to pause and reflect on the storytelling technique she employed in A New Home. The depth and excitement she brings to the page here with a simple but effective gimmick is too good to cast aside as a single experiment. There are new dimensions here for Franklin to explore, and a new light to view comics through.