This is your brain on two million years of evolution

Yuval Noah Harari's Sapiens has famously been praised by both Bill Gates and Barack Obama. Those names really make you sit up and take notice. But they also signify something important about the book itself.

We had a meaty conversation about Sapiens at last night's Reading Through It Book Club. We talked about our origins as a species, the importance of belief, the weight of fictions and narratives in the construction of our civilization, and the way we fool ourselves a thousand times before breakfast. For every line of questioning that I spun into nowhere — despite my best efforts I seriously sounded like a dorm-room stoner for much of the discussion — other book club members offered substantial criticisms and thoughtful complements to the text.

Some members of the club accused the book of being aimless and lacking a thesis. Others argued with the idea that the time before farming, when humanity was mostly interested in hunting and gathering, was the paradise that Harari painted it to be. Some enjoyed the break from election stresses that Sapiens's ten-thousand-foot view of the human race provided.

Along those lines, one big takeaway from the book was the way Harari tries to demythologize the human race. We are not the end result of millions of years of evolution, nor are we the pinnacle of life on earth. But the very thing that makes us special — our ability to cooperate through shared communication and stories — also convinces us of our own supremacy as a species. We are gods in our own minds, Harari argues, and he implies that it might be best if we let go of that arrogant assumption.

Perhaps the sharpest complaint leveled against Sapiens last night was that, though it was first published in 2015, Harari does not predict the rise of nationalism. He's not a fortune teller, of course, but his failure of imagination undercut his suggestions that civilization is moving forward, beyond racism and regressive thinking. It seems as though Trumpism and Brexit likely took him entirely by surprise.

And Trumpism and Brexit also took Barack Obama and Bill Gates by surprise. Perhaps we should read something in to Gates's and Obama's support for Sapiens. Both men are profoundly popular and transformative figures in American history, but both men also failed to see the world that was lying in wait just around the corner from their ascendancy. What if Sapiens isn't a book about how we prepare for the future, but is instead a tribute to the great minds who built our past? What if the world is actually meaner and dumber and less logical than the world Harari presents in Sapiens? What if the view from 10,000 feet doesn't provide anything of value to those who live in the dirt every day?

Maybe the election ate your brain last night. It's okay! It happens. But after a night of nitty-gritty election watching, it helps to take a step back and absorb a big-picture view. And the pictures don't get much bigger than Yuval Noah Harari's book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. This book is beloved by thinkers ranging from Barack Obama to Bill Gates, and it's reshaping the way we talk about human behavior.

Tonight at Third Place Books Seward Park, we'll be discussing Sapiens as part of our regular Reading Through It Book Club. The conversation starts at 7 pm. No purchase is necessary. This should be a great way to reframe our goals in the next two years as we prepare to take the country back from regressive forces. I hope you'll join us.

Book News Roundup: Meet Skull-Face Bookseller Honda

- Zee Brewer, a transgender and nonbinary individual, has filed a complaint against Portland independent bookseller Powell's for discriminatory behavior. Aaron Mesh at Willamette Week writes:

Brewer's frustration started not long after they began working at Powell's and Brewer learned that neither of Powell's corporate office restrooms was gender neutral. (The corporate office is located across the street from the famed City of Books that takes up a square block in the Pearl District.)

That meant whenever Brewer had to use the restroom, they had to walk across the street to the bookstore, up three flights of stairs, to the public gender-neutral restroom there. The break time allotted for this journey: 10 minutes.

- Michael Lieberman at Book Patrol explains the bookseller protest against Abebooks that is taking place this week:

For the week of November 5 to 11, 2018, booksellers around the world will remove their inventory from Abebooks, an Amazon company, in a show of support for their brethren in South Korea, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Russia who were told they can no longer sell on their platform.

- Polygon introduced me to Skull-Face Bookseller Honda, a new anime that speaks directly to my interests. Please be advised that there is a very brief flash of NSFW material in this video. But please watch it anyway. Whoever made this video clearly has a ton of bookseller experience.

How Kim Kent is becoming a Seattle poet

Our October poet in residence, Kim Kent, has taken a very long route to arrive at exactly the point where she wanted to be. Kent always considered herself a writer, but she didn't always know that poetry would be her calling.

Growing up in New England, Kent read and wrote fiction. "I wrote a lot of historical fiction as a child," Kent says. "I don't think I had great historical knowledge, so there was always a plague and an enthusiastic, rebellious girl on horseback." Her undergrad minor was in creative writing, but the pull of poetry proved to be unstoppable.

By the time Kent moved to Seattle in 2010, she knew that she wanted to write poetry, but she was having trouble getting motivated. That all changed when she discovered the Hugo House and started to take poetry course. "I think the first class I took was with Kary Wayson," she says, and pauses. "Though it might've been Kate Lebo."

In any case, Wayson's yearlong intensive poetry class proved to be a breakthrough for Kent. "It was intense. She's a great teacher — she's very honest, and for me it was the first time I talked about revision and craft." Kent says the class was "super-generative" and it served as "an introduction to Seattle's literary scene," introducing her to local figures like Kevin Craft.

Kent's poetry is durable — it's constructed thoughtfully and it stays with you. The imagery in her poems resonate in your mind long after you've looked away. Many poets are good at creating one solid moment in their poems. Other poets have a gift for inspiring emotion. Kent's poems do both at once: she sets a scene with clarity and precision, but she also leaves a door open for ambiguity's sake. There's always an unanswered question, an unexplored path, just begging for your attention.

After finding her way around Seattle's literary scene and starting to develop her voice, Kent left Seattle to attend grad school in Spokane from 2015 to 2017. She's a rare Washington poet who's conversant with the literary scene on both sides of the mountains. "For whatever reason, each side of the state has their own opinions of each other, but I felt very lucky to have a home in both."

In recent years, Seattle poets have left town due to rising rents and moved to Spokane. Now, those writers are coming back to visit with surprising regularity. "I went to readings at the Hugo House on Wednesday and Thursday of last week," Kent says, "and both of them had Spokane poets in them. I think the more we can combine our scenes, the better."

That said, Kent feels like she's at home in Seattle. She likes how Seattle's scene "seems very authentic to the city. I like that people are hustling, and even though it isn't always easy, people are showing up for each other and supporting each other more and more."

One of the ways that Kent is showing up for the community is her acceptance into the Made at Hugo program, which provides young Seattle writers with a peer group and a run of the writing organization's resources. Kent is making the most her time as a Made at Hugo Fellow, attending plenty of readings and classes. Right now she's a part of a class by local author Keetje J. Kuipers, which she says offers plenty of new perspectives in a workshop setting. At the end of the program next year, Kent hopes to have a good draft of a first poetry collection to send out to publishers.

Kent seems to be learning as much as she can from a great tradition of Seattle poets. She counts Elizabeth Austen's class about public speaking as one of the most influential learning experiences of her life as a poet, and she's a big fan of Frances McCue's most recent collection. As she talks about her past and her plans, it's clear that she's very deliberate in her intent to place herself in the Northwest poetic tradition. She's proceeding thoughtfully and with great care to ensure that she's adding something of great value to our community.

The perfect pamphlet for politics and prayer and poetry

My favorite poem in the collection is "A Prayer to Cathy McMorris for the Preservation of My Health Insurance" and it begins:

Cathy, when you were a doctor

did you hate how our government bossed you,

how The Man just had to get his hand

in there? I need to know, Cathy, I'm scared.

At a time when elected officials barely seem to care about their constituents, this book takes that helpless feeling and amplifies it. This is a call from a constituent to her uncaring representative, and it's the perfect book to read on an Election Day that could go down in history as the day on which the union was saved or lost. I'm willing to bet that a few atheists out there are throwing some prayers into the air over these election results, just to cover all their bases. To those of my fellow atheists who are right now praying like Lebo to their uncaring representatives, all I can really say is this: Amen.

Seattle on the y axis

Published November 06, 2018, at 11:52am

A new book offers to help you see Seattle in a new light through the magic of data visualization. Does Seattle look different when viewed through graphs and charts?

Refusal of the Return

Pale scattered

immunosuppressant ovals

chalky steroids;dispossessed seedpods

tickle at the aural hum

of childhood sleepwhen I might hear

river rush in my right ear

(Burntboot Creek, forked

from the Snoqualmie River)

susurrus of waterfall

in my left.Austere and ascetic nomenclature:

Lindeman crossing into Buck,

North Fork Railroad Trestle,

Rattlesnake Lake,

Joseph, Judith, Seneca, Astrid.Star women ambling

homeward without much fuss;

never begging for fast water

salt or skin or iodine,

not a meager sliver of apotheosis.Tokul — darkest water,

utterly still.

Read a chapter from River of Angels, courtesy of sponsor Abbe Rolnick

Rolnick is sharing the first chapter of River of Angels with our readers this week. One reviewer calls the book "Atmospheric, intricately plotted and fast paced ... a dive into an exotic, dangerous and sultry world." We can vouch that it's the perfect escape from a long Monday afternoon — instantly engaging and endlessly intriguing. Try a paragraph, then click through for the rest.

Monica hurried down the cobbled road with the sun’s rays on her bare shoulders. She smiled, listening to the chaotic rhythms of the streets. Music blared from storefronts, and vendors at each corner offered up helado — shaved ice with flavoring. Her new home wasn’t that different from New York, less tidy but just as crazy. She still wasn’t used to the openness of the police toward drinking cerveza outside of restaurants or bars. Different laws, different customs. More ...

Sponsors like Abbe Rolnick make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you can sponsor us, too? We're sold out through January 2019, and we haven't released the next round of slots — which means this is a great chance to reserve dates for February through July before they sell. Just send us a note at sponsor@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from November 5th - 11th

Monday, November 5: The Best Bad Things Reading

Seattle author Katrina Carrasco debuts her new novel, The Best Bad Things, with conversational help from beloved Seatle writer Nicola Griffith. The Best Bad Things is crime fiction about a woman who is a "detective, smuggler, [and] spy" in the year of our lord 1887.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Tuesday, November 6: Ellen Forney

Look, first of all, please vote. And then after you vote, you can treat yourself with a reading by one of Seattle's very finest cartoonists, Ellen Forney. Her fabulous book Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo, and Me was selected as this year’s UW Health Sciences Common Book. Hogness Auditorium, UW Campus, https://www.facebook.com/uwhscommonbook/ 5:30 pm, free.Wednesday November 7: The Library Book Reading

Susan Orlean is one of the best non-fiction authors in the country. Her latest, a history and examination of libraries, is the textbook definition of a balm for troubled times. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.Thursday, November 8: Seattleness Reading

Here's a fun one for locals: Seattleness is a collection of charts, graphs, and maps celebrating all things Seattle. Both data visualization nerds and map nerds will find plenty to geek out over in this one, and you're guaranteed to learn something new about Seattle every few pages. Rainier Arts Center, 3515 S Alaska St, 725-7517, http://www.rainierartscenter.org/, 7:30 pm, $5.Friday, November 9: Diving Into the Wreck

It's time for the Hugo House's reading series, which offers three writers and a musician an opportunity to create new work on a theme. The readers tonight are Lauren Groff, R. O. Kwon, and Kim Fu (whose The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore was one of the books I loved most last year.) They'll be joined by Seattle musician Shelby Earl, and the theme is "Diving into the Wreck," which is not the best Hugo House theme, but I'm sure these artists will do something great with it. Hugo House, 1634 11th Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org, 7:30 pm, $25.Saturday, November 10: Shout Your Abortion Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Sunday, November 11: Subjective Geography Reading

Seattle poet Madeline DeFrees was interested in place and how it affects interior life. This celebration is a debut party to launch a new collection of essays by DeFrees, many of which are about that very subject. At this reading, the book's editor, Anne McDuffie, will be joined by Laura Jensen, Sharon Bryan, and Jennifer Maier. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 5 pm, free.Short Run is Seattle's best book festival

This report was written by Paul Constant and Dawn McCarra Bass.

The Short Run Comix & Arts Festival on Saturday felt just as busy as ever, but it didn’t quite feel as crowded as the most recent iterations of the festival. It took us a couple times around the floor to figure out that there was one fewer row of artist tables in Fisher Pavilion, which created an easier flow throughout. No more smashing into some random person’s backpack when you turn to check out an especially enticing comic on someone’s table! No more stuttering steps necessary as you chug behind a small army of slow-walking looky-loos!

From a visitor’s perspective, Short Run was as smoothly run and as packed with intriguing new titles as ever. The show has grown nicely into Fisher Pavilion — so much so that it’s hard to remember when it was held at Washington Hall or in the Vera Project. Short Run is home, and the festival reached a point in its development when most people involved know what to expect. “Short Run” has become a shorthand for a very particular aesthetic: supportive, enthusiastic, eager for new work and new talent and new artistic perspectives. It’s becoming an institution of its own. Here’s what the institution meant to us this year:

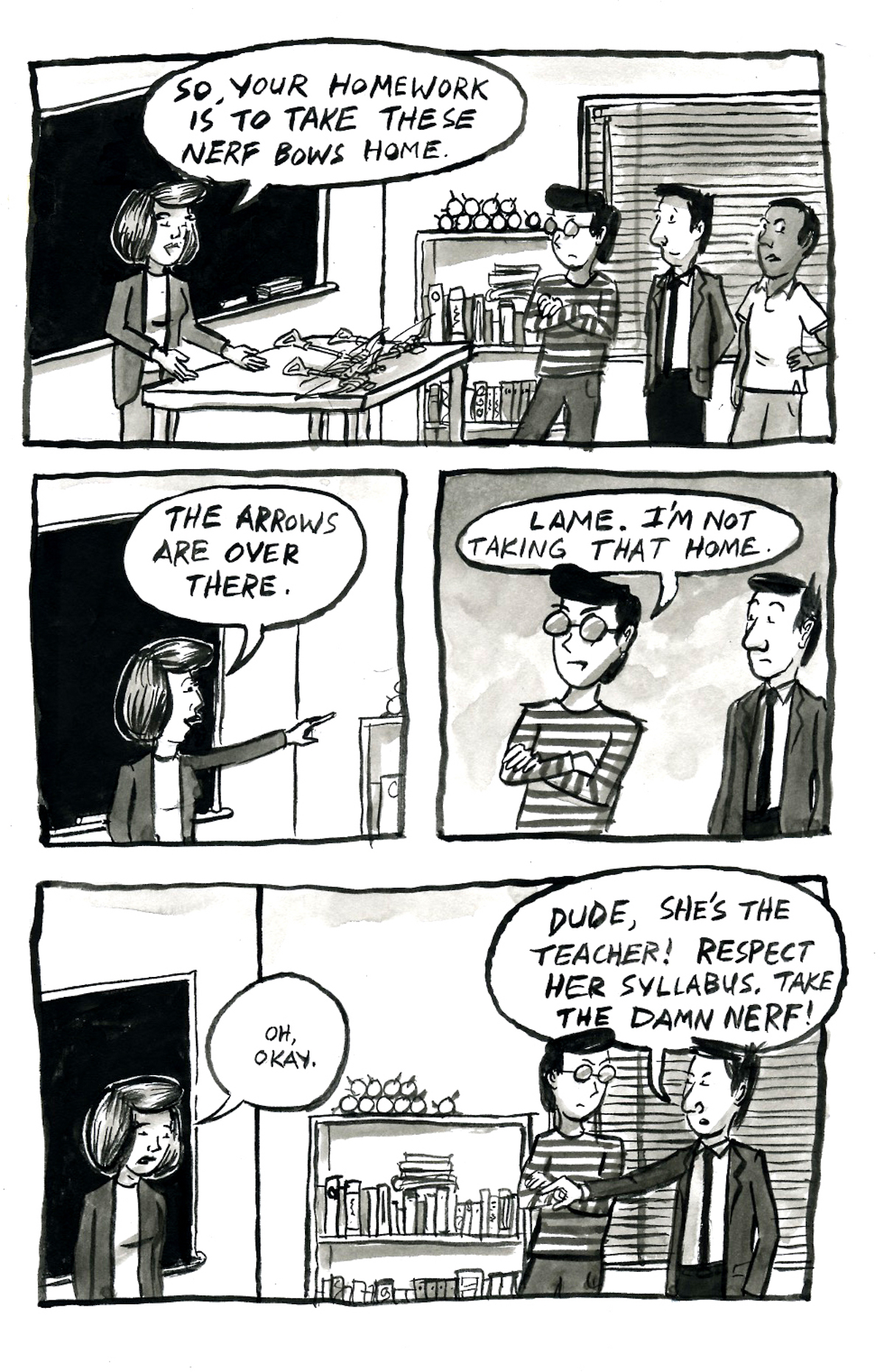

Hey, being an ally is super hard, nobody’s saying it isn’t. Here’s some good news if you’re white, cis, male, or (god forbid) all three: there’s a new volume of Shana T. Bryant’s destined-to-be-a-classic Terrible Allies: Vol. 2: Still Terrible. Bryant is exceptionally good at skewering the haplessness of privilege, and in the small universe of these comics (usually two to three characters at most), she shows us exactly how bad good intentions can be. She’s also a genius at capturing mood in just a few lines. Some of our favorite sequences repeat images with subtle changes to the shading and focus that deliver endless varieties of clueless self-consideration.

This is a perfect example of the many, many things comics do well: it’s not easy to hold up a mirror in a way that’s palatable enough to be effective, but Bryant uses the form to build empathy and force perspective the way she wants it. Bryant works in tech in Seattle, so it’s a miracle she draws with as much gracious humor as she does — but it’s because her characters are both gracious and unyielding that the book gets its message through. In our brief time at her table, we chatted about her customers’ fear of finding themselves in the pages: As Bryant said, a lot of people pick up her books with a wince; nobody wants to recognize themselves as the bad guy. But that’s the only way to get better. And just a reminder: “Real allies vote. In every election. (Even the boring ones.)” Vote!

Friends, have we talked before about how Greg Stump is one of Seattle’s best cartoonists? It struck us reading Blockhead, the collection of the last five years of Stump’s short works, that we maybe don’t praise him often enough. Here are strips covering a wide range of topics — a memoir strip about an eleven-year-old Stump trying to hustle a contributor copy of Hustler by submitting a “cartoon about prostitution and venereal disease” to the pornographic magazine; a story of a ghost who just wants to go bowling; reviews of author readings at Seattle Arts & Lectures events; a monologue from God about how He is jealous of Santa Claus. Stump makes it all look so effortless that it’s easy to forget how much craftsmanship goes into every single panel.

Every Short Run, we ask the more established cartoonists a single question: Who have you seen at this show who is new and local and wildly promising? This year, young Seattle cartoonist Lauren Armstrong was the name most often mentioned. Her comics don’t look like traditional comics — ”it feels like she’s coming from outside the medium,” someone told us, quickly adding “in a good way” — which makes Armstrong an outsider in a field of outsiders. Armstrong had several “books” at Short Run that were simply one big comics page, folded down to a tiny little square package. Penis is the story of a skateboarding accident that severs a skater’s penis down to a bloody stub. While doctors try to reattach the severed penis “with modern medicine,” the anthropomorphized stub decides that it doesn’t miss the penis at all. (Its first words: “FRESH AIR…”) It’s an intentionally ugly strip, but all the people who sent us Armstrong’s way were right. These comics feel like they’re from an alternative universe, one where comics never got sidetracked with superheroes and instead were co-opted by fine art instead. We can’t wait to see more of Armstrong’s work in the near future.

We’ll have plenty more reviews of Short Run books in days to come on this site. But what no laundry list of Short Run hauls can convey is the feeling of what it’s like to be in the room. When you’re part of the bustling crowd, seeing familiar faces and looking out for exciting new art, Short Run feels like the most hopeful place on earth. You just know that if you look hard enough, you can find a good friend you haven’t seen in months. And you also know that if you cast your eyes far enough from one wall to the other, you’ll see a kind of artistic expression that you’ve never before imagined.

Aside from all the talk about politics — seriously: vote, okay? — and all the concern for Seattle as an increasingly expensive place that no longer welcomes artists, the individuals we talked with were personally hopeful. Marc Palm was still riding high from a recent gun responsibility comic going viral, and he was eager to produce more work for Mad magazine and other outlets. The publishers of Thick as Thieves were looking forward to producing a new issue in early 2019 that they hoped would usher in a new era for the magazine. Short Run co-founders Eroyn Franklin and Kelly Froh both had new work at the show that demonstrated their continuing affection and curiosity for the artfrom. People were hard at work planning new projects, scheming together about possible events, and scheduling times to get together and talk about how to turn comics on its ear.

No matter what kind of political conflagration is happening around Short Run, the happy fact is that Short Run remains the same. This is not a show that will break your heart. This is a show that will welcome you and reward your patience and remind you why you fell in love with art in the first place. You leave Short Run ready for the year to come.

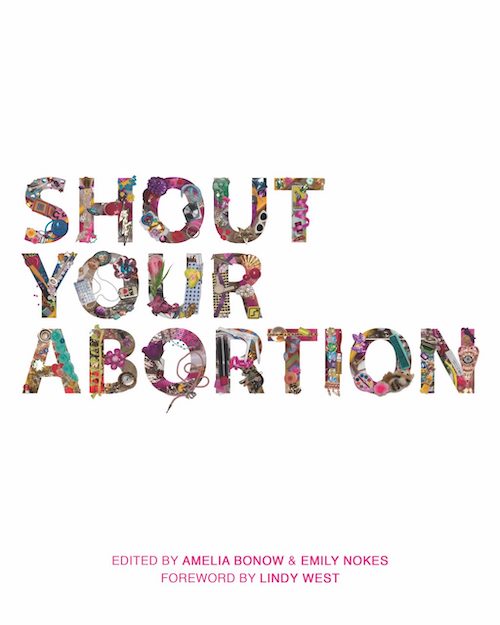

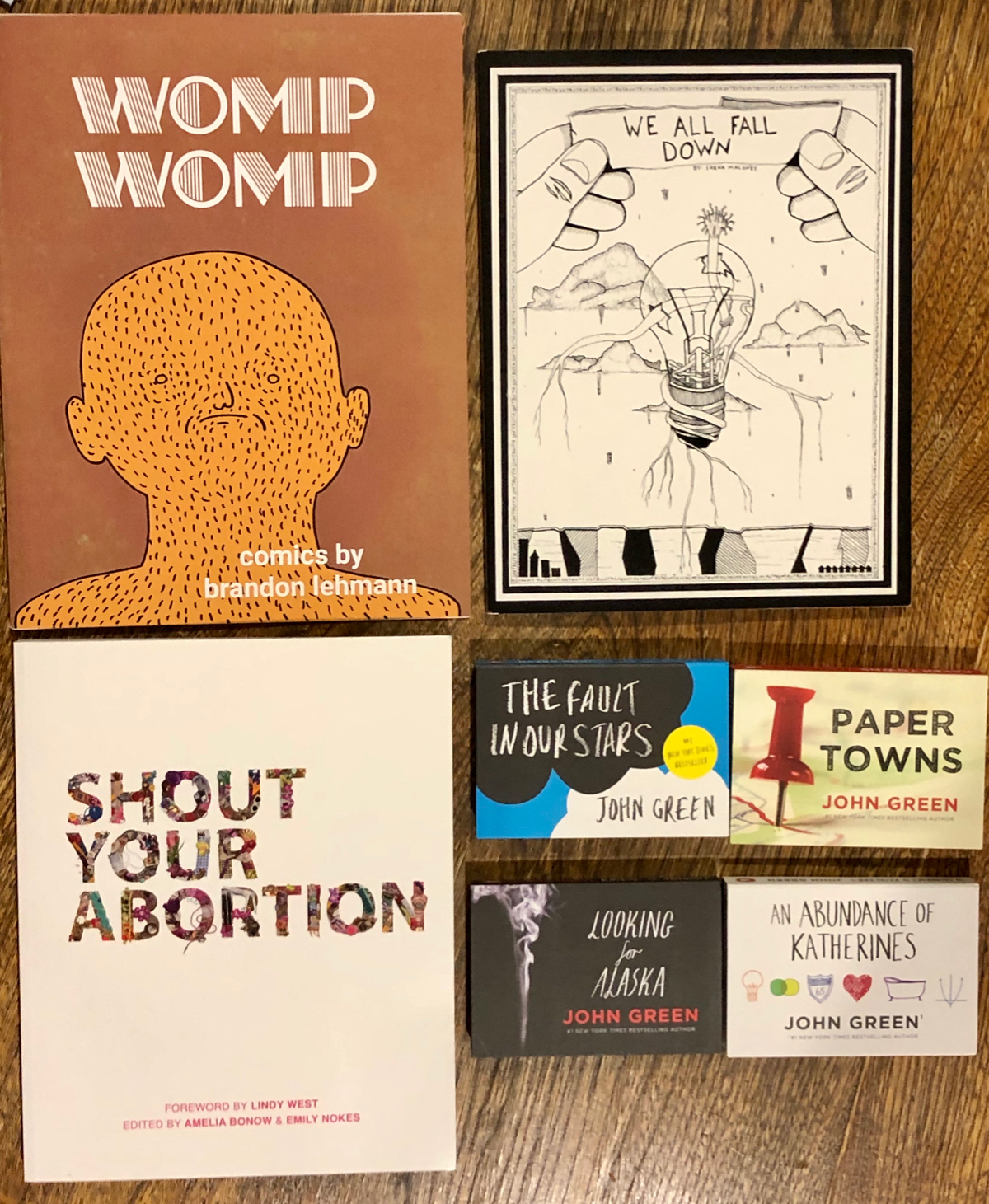

Literary Event of the Week: Shout Your Abortion anthology launch party at Elliott Bay

Shout Your Abortion is an international movement, but it was created right here in Seattle, and most of its organizing work is still done here. I've encountered men and women — older, mostly, but not always — who think the name itself is too loud. They bristle at the word "shout" in conjunction with the word "abortion." They think it's too un-reverential, that it's too, well, loud.

"We are conditioned to speak about abortion with reverence and a bit of melancholy, if we speak about it at all," Lindy West writes in the introduction to the new Shout Your Abortion anthology. She continues, "But feeling relieved after my abortion didn’t make me part of some radical vanguard, it made me utterly mundane."

In a foreword to the book, Amelia Bonow, the founder and chair of SYA, says that she wrote about her abortion in a public Facebook post in the hopes of launching a conversation from a "constructive place of discomfort." That post, with the help of West and dozens of other Seattle women, eventually became the SYA organization.

And now, there's a book. Shout Your Abortion is in many ways a polished version of the SYA zine I wrote about back in June of 2016. It collects the voices of women who have had abortions, tells the stories of abortion providers, and offers inspiration for anyone who wants to take up the SYA charge through art or politics.

The personal stories are from a diverse array of women including lots of Seattle writers (Lesley Hazleton, Angela Garbes, West, Bonow) and they're illustrated with big full-color photographs of the women looking strong and happy and defiant and, well, perfectly normal. Shout Your Abortion is illustrated throughout with photos and collages and comics (Seattle cartoonists Tatiana Gill and Robyn Jordan both contribute autobiographical strips) and lots of SYA paraphernalia. Maybe here is a good place to disclose that the book is co-edited and designed by Emily Nokes, who, along with West, was my coworker at The Stranger for many years and is still a dear friend.

All of these stories are incredibly powerful, but the words in Shout Your Abortion that struck me the deepest are the slogans, which feel so honest that they're practically transgressive:

OUR STORIES ARE OURS TO TELL

THIS IS NOT A DEBATE

EVERYONE KNOWS I HAD AN ABORTION

ABORTION IS NORMAL

I USED TO THINK ABORTIONS WERE BAD, BUT NOW I DON'T

THANK GOD FOR ABORTION

The shouting is necessary because for too long, even self-described progressives have whispered about abortion, been ashamed of it. Bill Clinton propagated the idea that abortion should be "safe, legal, and rare." But here's the thing: that kind of thinking is a concession. It's saying that women's sexuality should be restricted and controlled. It's saying that abortion would not exist in a perfectly just world. It's saying that abortion is something that should not be discussed in polite company.

And here's the thing about polite company: polite people don't get shit done. Hence, the shouting. We have to shout about abortion now so that we can talk about it wherever we want in years to come.

This Saturday, Bonow and Hazleton and contributors including Miki Sodos, Alana Edmondson, S. Surface, Alayna Becker and Shawna Murphy will launch the Shout Your Abortion anthology into the world with a great big party. Expect it to be pretty loud.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for November 4, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

If you haven’t voted yet, isn’t Sunday morning the perfect time to do it? Settle in with an election guide or three, a heavy marking pen, and your ballot, and make yourself heard. Your vote counts, and your voting counts. It’s a signal that you give a damn, and that other people should too.

I Will Not Be an Invisible Trans Woman

Gabrielle Bellot, a transgender woman, writes about what it’s like to have your government try to define you out of existence. Vote with Gabrielle Bellot!

As a black American, as a gay man. I understand this betrayal of a flag, too, this way that you can live in a country and have the profoundest sense that it wishes you did not live there, that it even wishes, perhaps, you lived in the “undiscovered country,” where no one lives at all. I know it as a person of color, as a woman, as someone who grew up in another country, and, above all, as a transgender person in a moment when I am told — casually, by a leaked memo, which says that the Trump administration wants to create a legal definition of sex as, according to The New York Times, “a biological, immutable condition determined by genitalia at birth” — that our government believes people like me should not exist.

‘You descend into hell by coming here’: how Texas shut the door on refugees

Justine van der Leun pursues the story of Wassim Isaac, a Syrian refugee who had the bad luck to ask for asylum at the border in El Paso, where only 3 percent of such requests are granted by judges with more or less absolute power. Vote on behalf of Wassim Isaac!

Under the Trump administration, the concept of due process has been further subjugated by a nativist ideology at odds with the American ideal of an open, egalitarian, multicultural society. (In February, the federal agency that issues green cards and grants citizenship changed its mission statement from a pledge to fulfill “America’s promise as a nation of immigrants” to a vow to adjudicate immigration requests while “securing the homeland”.) In June, following an uproar related to the administration’s separation of families at the border, Trump tweeted his thoughts: “We cannot allow all of these people to invade our Country. When somebody comes in, we must immediately, with no Judges or Court Cases, bring them back from where they came.”

Voter-Suppression Tactics in the Age of Trump

Jelani Cobb sees voter suppression as a long game — with short-term benefits for a privileged few and lasting consequences for the nation. Vote, and preserve the right for everyone to do so!

The xenophobia and the resentment that Donald Trump stirred up during the 2016 election are fundamentally concerns about the future of the American electorate. (His reported comment that too many people are immigrating from “shithole countries” in Africa and the Caribbean was paired with a lament that not enough are coming from Europe.) He has repeatedly stated that he lost the popular vote because non-citizens voted for Hillary Clinton. Last Thursday, at a rally in Montana, he suggested that Democrats were responsible for a caravan of migrants now heading north from Honduras, because they “figure everybody coming in is going to vote Democrat.” Kemp, likewise, claimed that Abrams wants to let undocumented people vote in Georgia. The suppression of minority votes is the homegrown corollary of this strategy — an attempt to place a white thumb on the demographic scale.

U.S. Law Enforcement Failed to See the Threat of White Nationalism. Now They Don’t Know How to Stop It.

White supremacists vote! Vote against them! I’m pretty sure Janet Reitman will.

While I happened to be sitting across the table from an admitted fascist who admires Adolf Hitler and has advocated (he says trollishly) “white Shariah,” I didn’t feel threatened by Will Fears. Like so many of the movement’s vague anymen, he presented himself as polite, articulate and interested in cultural politics, and though his views are abhorrent, he stated them all so laconically you might forget that he actually believes in the concept of a white ethnostate. And that’s the point: The genius of the new far right, if we could call it “genius,” has been their steadfast determination to blend into the larger fabric of society to such an extent that perhaps the only way you might see them as a problem is if you actually want to see them at all.

Stacey Abrams embraces progressive politics. Even in her romance novels.

I so wish I could vote for this amazing, badass, fearless woman, who is overturning politics in Georgia and assumptions about her chosen genre. Since I can’t, I’ll vote where I can. You should too.

If she wins her election, Stacey Abrams, the Democratic candidate for governor of Georgia, will become the nation’s first black female governor. She’d also be the first governor who writes romantic suspense novels — eight of them, in fact, published under the pseudonym Selena Montgomery.

Whatcha Reading, Levi Fuller?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Levi Fuller is a Seattle based musician, who plays in Levi Fuller & the Library, and The Luna Moth, and is the founder of Ball of Wax Audio Quarterly (of which he says that he's "really been meaning to come up with a tagline for like "the longest-running quarterly CD-R compilation series in Northwest Seattle" or something), and is the Administrative Coordinator at Jack Straw Cultural Center, where he manages their residency program for artists of all genres and disciplines and assists with daily operations. You can go see Levi Fuller & the Library on November 17 at the Blue Moon Tavern for their EP release party, and pick up the EP itself the new EP (which features a cover illustration from SRoB contributor Clare Johnson) on November 11th.

What are you reading now?

Right now I'm reading Beyond Birds & Bees, by Bonnie J Rough. It's a pretty new book that happens to be timed perfectly for me and my wife, as parents of a just-turned-three-year-old. It's filled with practical and thoughtful advice and ideas around raising kids with healthy outlooks on sexuality, their bodies, gender, etc. — you know, all that stuff we do so well in this country. I could not recommend it more strongly to anyone with a kid, the younger the better. As a generally liberal person who still has a lot of weird New England protestant hangups, it's eye- and mind-opening in the best ways.

What did you read last?

Before that I read Ijeoma Oluo's So You Want to Talk about Race, which has been on my list for a while. (I only noticed when I started the Rough book that they're both published under the same imprint — so shoutout to Seal Press for publishing some badass local women.) As a fan of Oluo's work and someone who's always looking for ways to be a less harmful version of a white man, I knew I wanted to read this the moment I heard about it, and it did not disappoint. Even for someone who pays attention to these issues and has gone through some anti-racism and racial equity training, there was still plenty to learn here. As much as all parents should read Bonnie Rough's book, all white people should read this one.

What are you reading next?

My "what's next" is often left up to whatever hold I forgot to reactivate at the Library, but right now I specifically want to go back to some fiction (but I will keep with the theme of badass local women). Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum was working on her short story collection What We Do with the Wreckage when she was a Jack Straw Writer, and I enjoyed what I read and heard of it then, so I can't wait to read the whole collection.

October 2018's Post-it note art from Instagram

Over on our Instagram page, we’re posting a weekly installation from Clare Johnson’s Post-it Note Project, a long running daily project. Here’s her wrap-up and statement from October’s posts.

October's Theme: Little Things

Sometimes when I look back at post-its from certain times, I feel self-conscious, embarrassed to expose how caught up in my own personal moments I can be. At any given date some huge thing was happening in the news, and yet here’s my post-it from that night, and it’s talking about... the weather. How excited I am that it’s raining—I have SO MANY of those (my rain love is, admittedly, unwaveringly earnest and pervasive). Or it’s about my bad sleep; something a friend said; that movie I just watched; a strange sentence overheard outside the grocery store; looking up at the exact right moment to discover a house’s fancy weather vane far above me during a walk; humdrum magic of yet another cup of tea. It’s been over a decade now of making a new post-it each night, and while the bigger world certainly leaves its mark, most of the drawings are actually little things. I worry they look trivial in light of everything else developing at the same time; in recent years, part of me feels guilty not using every bit of space I have to vigilantly shout about what’s happening on a larger scale. But it also makes me happy to uncover all these tiny observations, interior thoughts, ordinary interactions—little things that make each day so much more than the news. I don’t know what redeemed that late February day, made me feel better at the last minute. It could have been any little late night detail—I just like to remember that it can happen, and it doesn’t have to take much. In March, my friend’s boyfriend’s friend was passing through town again after lots of travel—I won’t ever know him well, but he’s lovely to hang out with when he’s around. The idea of him in Hawaiian shirts added a funny mystery to his personality that I enjoy thinking about. PJ Harvey days means an April already packed with mundane rejection and mess and anxieties suddenly escalating into real fear. Clustered attack of homophobic hate mail from someone who knew where I worked—there’s not really much that fixes that. Walking across the city from thing to thing, listening to Rid of Me on my headphones—the little solution to what happened inside me, my anger and helplessness, the rawness. That old favorite helped me hold myself, feel known, remember where I’m powerful. And in May playing with a dearest dear friend’s baby—I’m smiling just writing this. She really gets my look-my-fingers-are-a-little-creature-making-funny-noises-and-walking-on-your-arm jokes.

Kissing Books: Romancelandia

Every month, Olivia Waite pulls back the covers, revealing the very best in new, and classic, romance. We're extending a hand to you. Won't you take it? And if you're still not sated, there's always the archives.

Writers like to say say there are only so many basic plots in the world. (The exact number varies depending on who you ask.) It can be illuminating to consider these broad categories, imperfect though they may be. Especially when we pair them with equally broad categories of setting. Sometimes when you’re trying to trace romance taxonomy you have to step back and squint a little at the outlines.

London-set romances are frequently Person Versus Person: they turn on questions of inheritance, alliance, status, power, and secrets. Ballrooms and bedrooms figure so prominently because they’re where people come together for social and sexual intercourse — but even those rare and refreshing stories that center lower- and working-class Londoners as well as the upper crust (recent reviews of KJ Charles, Cat Sebastian, and Jude Lucens come to mind) have a distinctly societal bent. These books are about people as a super-organism, as busy and interdependent as a hive of bees in honey season. They ask how we exist in relationship to one another. Duty, honor, and obligation, all social forces, crop up like caltrops in the path of true love.

Historical romances in the American West, on the other hand, are commonly more concerned with Person Versus Environment: turning a piece of land into a town, mining precious metals, raising cattle, eradicating the natives (who are not given room to exist as People in many of these stories). We see towns and cities but as newborn ideas, sketches of the maps we know — these places are works in progress, mere gestures waving at the future inhabited by the reader. Most Westerns these days show up in inspirational romance, though there’s a stubborn, inclusive streak of queer and race-aware historicals that I for one would love to see explored more often. Especially since the environment in America is so often hostile to marginalized folks — and this can be a satisfying framework for a romance. For example: Sharon Cullars’ Gold Mountain and Backwards to Oregon by Jae, or one of Beverly Jenkins’ small town Western settings (have you read Forbidden yet??? it is perfection).

And then we turn to New York. And things get complicated.

Though there are standout historical gems to be found in this setting (Joanna Shupe, of course, and the EE Ottoman novella reviewed below) New York-set romances are largely contemporaries: the Harlequin Presents-type billionaire bent on revenging himself on his ex-business partner’s daughter, the secretly kinky CEO whose polished exterior hides a messy, wounded Dom, the sweet but ambitious heroine determined to make it in the hustle of America’s largest and most quintessentially American city. At first you might think that geography aside there’s little common ground between sweet Sarah Morgan rom-coms, the acid-tongued chick-lit trend of the 90s, and the seemingly endless wave of erotic or New Adult romances with dramatically lit covers and miles of tortured backstory — but then you look past the differences in tone, and you realize that all these arcs are very much the epitome of the plot known as Person Versus Self. It’s a story about recognizing and reconciling identities. Who are you really? Who do you want to be? There’s a Surface New York, a mythical place developed in a thousand books and films and tv shows, that presents the city as a canvas against which individual characters prove their greatness. (This is by no means limited to the romance genre: looking at you, every Great American Novelist.) The soaring, populous, silver-glass skyline becomes a mirror in which our main characters learn to better see their own outlines. Even in romances that take care to push past that shiny surface, the core arc is preserved — such as in Alyssa Cole’s A Princess in Theory, which presents us a much more nuanced glimpse into the city’s real-life demographics. Ledi and Thabiso/Jamal both have to alter their conceptions of who they essentially are before they can truly open their hearts to one another.

And of course, true to Romancelandia, as soon as we try to establish a rule we find plenty of exceptions that shatter it. This month’s books include a historical New York-set novella, a Regency that explores some of what it means to be black among the British aristocracy, a bicoastal f/f romance, a British small-town paranormal, and a Cornwall Regency miss who’s taken up smuggling for all the right reasons, naturally. Because even in romance, where setting looms large, geography is not entirely destiny.

Recent Romances:

The Craft of Love by EE Ottoman (self-published: trans m/bi f):

A trans silversmith and a heartbroken quiltmaker meet and fall in love in Gilded Age New York. They admire one another’s work and designs. They admire one another’s kindness and intellectual pursuits. The merest brush of hands makes their hearts flutter and gazes grow intense. Eventually, they confess their feelings. On paper it sounds like there’s not enough conflict to sustain even so short a story as this one. In practice, though, it’s as wildly engrossing and terrifying as the first time you look at someone and wonder: She’s so amazing—what could she possibly see in me?

Silversmith Benjamin Lewis is on the mend from a long illness, itching to get back to his smithy. While puttering about the house he discovers a cache of dresses made for him by his late mother: beautiful embroidery, but made for a person who Benjamin never truly was meant to be. But the fabric is valuable and the embroidery truly spectacular, so his sister encourages him to have the dresses turned into a quilt of some kind. She believes this could help Ben come to terms a little with his complicated feelings about his mother and their fraught relationship.

Quiltmaker Remembrance Quincy (oh, such a name!) has kept her heart guarded ever since her friend and beloved Hope abandoned her. She is drawn to Mr. Lewis’ gentle nature and warm regard — and figures out the truth of his particular identity without having to be told — but she is not sure if she wants to risk her heart again, when it was such a painful experience the first time. The two talk, and go on walks, and meet one another’s families, and their feelings blossom little by little. All while we catch glimpses of the early labor movement, Abolitionist debate, and the switch from sail power to steam. It’s a narrow window, but a lovely view.

This novella is as slender and delicate as a line of feather stitch in linen thread — and is just as quietly strong. It has the careful, deliberate kindness of voice I have come to associate with trans romances from authors like Austin Chant and RoAnn Sylver — though admittedly self-selection might be responsible for what looks like a trait of the subgenre. It’s not only that I’ve grown tired of grimdark, and misery for misery’s sake, in my fictional worlds. Reader praise of a book so often sounds like violence: we talk about our hearts being wrecked, about stories that kill us, about sadistic authors who torture and murder us as well as their characters. And that can often be quite fun! But it’s just as important to have something sweet, something kind, something healing to read when we’re sick down to our souls. This book will not hurt you. It will not tax you. This book is a warm cup of cider to soothe your aching hands, as you gently blow the steam away over the rim. Perfect for the cold days and busy holidays to come.

When she thought of him as he had been the night he’d walked her home, it made her heart quicken. There was a sweetness to him, a gentle patience that made her want to make him smile, to say clever things that would make his eyes shine. When she remembered their walk together and his visit to her workshop, she couldn’t help thinking of the movement of his strong hands, the shape of his mouth, and the long lines of his body. She wanted to see him relaxed and comfortable in shirtsleeves and with tousled hair, watch him play with his little nephew, and hear him laugh.

The Butterfly Bride by Vanessa Riley (Entangled: historical m/f):

To read Vanessa Riley is to feel the drape of lace against your wrists, as the rich scent of antique perfume fills the air. It’s transportive, is what I’m saying, over and above the usual. It’s a rare author who can write books that feel properly vintage without being stuffy, and it was terribly easy to lose myself in the author’s poetic, crystalline cadences.

Miss Frederica Burghley is the biracial bastard daughter of a notorious courtesan and a duke; she is illegitimate but acknowledged, a privileged but precarious position. Jasper is Viscount Hartwell, a widower still devastated by the loss of his beloved first wife, and burdened by three unruly daughters who are the terror of their many governesses. Jasper and Frederica wake up in bed together, fuzzy-headed, the day after Frederica’s father’s wedding. They have no memory of how they wound up there — except Frederica’s horrified recollection of bits and pieces of the night before: a hand breaking through her window, a whispered threat, a stolen jewel-box, and the ruins of a wardrobe viciously slashed to pieces. The duke and his new duchess will not put off their honeymoon, so the duke asks Hartwell to protect his daughter while he’s gone. Meanwhile Frederica plans to get herself quickly and properly married so the possessive thief will stop threatening her dearest friends and relations. Hartwell thinks this is a terrible idea — he’s not wrong. Frederica thinks Hartwell’s still too much in love with his first wife to give his heart easily — she’s right. There are weddings and suitors and a lot of meaningful piano playing, and (small content note) an emphasis on the dangers of historical childbirth that is both stark and refreshing in a genre that so often presents pregnancy as a wondrous miracle and gift, rather than the hugely risky undertaking it was in the days before ultrasounds, antibiotics, and regular hand-washing.

So yes, this book has a lot going on — but it feels deliberately layered, baroque rather than busy. And a soupçon of Grand Guignol at the end, to make the reader’s heart lurch with fear. This is the kind of romance plot where people stick stubbornly to painful decisions even after their hearts have realized the anguished truth; you kind of want to shake them, but in a good way. I was frequently reduced to keeling over on the couch and yelling argh out of sheer enjoyable frustration. Frederica in particular is a heartbreaker: lonely and fiercely brilliant but unsure of her place in the world, thanks to a rather unfeeling father and an awareness of how thin the ice she skates on truly is. She deserves every care and attention and it was a delight watching Hartwell slowly come to the same conclusion. This is surely a book to savor with a glass of fine brandy and a snowy window view; and how decadent that there are two prior books in the series for when you happily sigh and set this one aside!

Their gazes locked. He was on his knees, her hand pressed to his. If the carriage stopped, people would get the wrong idea. The question was, would he care?

Mating the Huntress by Talia Hibbert (self-published: paranormal m/f):

It’s the spooky season! I have to review at least one paranormal! But I am extremely picky about my paranormals, especially where shifters and fated mate tropes are concerned. Thankfully, Talia Hibbert (with whom I now share an agent, full disclosure) surprised us with a silly, sexy little paranormal and as always it’s a damn delight.

Luke is a Werewolf. A slavering, ravening monster, designed to prowl the night and tear the throats out of unwary humans. He’s strong. He’s fast. He’s nearly impossible to kill. Any reasonable woman would run screaming rather than follow him back to his cabin in the middle of a dark and lonely wood. But Chastity Adorno is no ordinary woman. She’s a huntress — well, she would be, if her family would let her join them on their killing nights. Something about a prophecy at her birth has left them a little overprotective. It grates on her nerves. So when a Werewolf starts showing up at her coffee shop, looking all human and sexy and shy despite being a monster, she thinks it’s her chance to finally get a kill and take her proper place among her sisters. She agrees to a date, and straps a silver dagger to her thigh.

Any romance reader steeples her fingers at this point and waits for it all to go beautifully, wonderfully wrong.

Paranormal romances trade in power metaphors — so most of the time most of the power ends up with the hero. (At least in het romances: I don’t have a strong sense yet of similar patterns in queer romance. But I’m working on it!) He’s often rich and immortal as well as super-strong both physically and magically. But I find I’m happier with paranormals that Take care to even the scales: Isabel Cooper’s dragons (both heroes and heroines), Shelly Laurenston’s alpha shifter heroines (just as murderous and horny as the dudes, and so fucking funny), and Alisha Rai’s witty, wicked Persephone retelling Hot as Hades. And we can definitely add Mating the Huntress to the list, because our huge, lurking, slavering, unkillable Were is almost instantly revealed to also be a comforting, attentive, eager-to-please bundle of joy. Who loves how tough and grumpy and violent the heroine is. There’s a particular type of hero I’ve come to call the Sex Puppy: hot, cheerful, usually funny but not too bright, and absolutely here for the heroine’s pleasure and happiness, exactly as she wants it, no more, no less. It’s a fun, comforting archetype, and this Werewolf is the Sex Puppiest shifter of them all. This book is a piece of pure paranormal candy, and I for one am here for any other glimpses into this world.

Christ, she wasn’t shy at all, was she? The hesitation, the demure smiles and lowered lashes — it had all been a trap. She wasn’t sweet or gentle or biddable. She was a bloodthirsty fucking murderer.

His heart sang.

Off Limits by Vanessa North (self-published: bi f/pan f):

I can scoff about Romancelandia dukes and billionaires all day, but you wave a half-glam, half-punk queer romance at me and all my capitalist criticisms go right out the window. Charity balls, sweaty concerts in dive bars, Hollywood celebrity exes, a glitzy and gay New York: I was totally in. This book is the first of a multi-author series set in two high-class queer women’s clubs: the Thorns in New York, and the Rose in LA. It’s stylish and sexy and sharp as all hell. I positively reveled in it.

Natalie is both a buttoned-up concierge for the Thorns and, as Nat, the lead singer of a sexy, angry, queer-as-hell punk band with a standing gig at a pub called the Bridgewater. Rebecca Horvath is a trust-fund kid, the child of Hollywood royalty — and, as a club member at Thorns, completely off-limits for Nat. (Hey, that’s the book title!) But sizzling chemistry, a criminal scheme, and Bex’s dad’s rush wedding conspire to throw them together over and over, and it’s no surprise when they give in and tumble into bed together. Nat is all edges and anxiety beneath her mask of control, and Bex is delicate as spun glass beneath her rich-girl polish, so their romance is less of a climb and more of a roller coaster as they try to find their footing in a world that honestly feels like near-chaos at all times. It left me breathless. The plot is full-throttle drama, every scene risking something or tightening a different piece of the tension — strong content note for a secondary character’s fairly intense suicide attempt — and I absolutely burned through the pages before I knew it. My one quibble is that after all the agony, the ending felt just a shade too easy. If you’ve enjoyed Anna Zabo’s queer rock romances, this is for sure the next thing you’ll want to pick up.

At the club, she’s invisible. On stage, she’s a giant. At home — mine or hers — she’s the light in every room and the warmth in the radiators. Without her, the bed is cold and the rooms are lonely, and I feel the weight of her uncle’s disapproval every time I glance at the photos on the walls.

This Month’s Historical Heroine Who Resorts to Smuggling for All the Noblest Reasons, Obviously:

Counting on a Countess by Eva Leigh (Avon Books: historical m/f):

I am shamefully behind in my collection of Eva Leigh books, but I buy every one as soon as I can because I’ve been reading her for a decade and there’s just something about the way she structures her plots that slips under my skin and gets my mental wheels turning every time. Continuing the trend, Counting on a Countess is a romantic meditation on the relationship between any individual and the state’s legal code. In particular, this romance uses the weight and weirdness of British law to anchor a fictive argument about the difference between laws-as-rules, and laws-as-social-obligations. Like my current favorite sitcom The Good Place, this book asks what we owe to each other while taking a blunt, critical look at a legal system that is both unyieldingly powerful and cruelly capricious.

We first meet our hero, Waterloo veteran and newly minted earl Kit Ellingsworth, cheerfully drunk and about to bang two — yup, two! — very willing opera-dancers. Kit has vague plans of building a pleasure-garden to chase away the shadowy memories of war, so he is first elated and then appalled to learn he will inherit his late commander’s fortune — but only if he marries within the next thirty days. At once we shift to our heroine Tamsyn Pearce, a bold Cornish smuggler who‘s wondering whether or not her new fence might want to kill her. Tamsyn took up smuggling to help her struggling hometown survive in the harsh economy of the Napoleonic Wars — but now her jerk uncle is planning to sell the manor house where they hide the French lace and brandy, and all her usual partners have bowed out for fear of discovery. She’s come to London to try and find a new buyer for the latest shipment, but when she’s turned down yet again she comes up with a new plan: she’ll marry a man with money.

Both Kit and Tamsyn have run afoul of the law, but with different intentions and with vastly different stakes. Kit is dismayed by the conditions of the will but the money is not a matter of life or death for him. Tamsyn, on the other hand, is fighting to keep her townsfolk from starving: the fishing hauls have been terrible and the post-war taxes burdensome. She fears being killed by the criminals she works with, but also knows that the law does not ensure her survival. This profound mismatch between Kit and Tamsyn creates friction, which keeps the plot engine turning — especially once the lawyers reveal a codicil to the will that makes all Kit’s financial decisions subject to Tamsyn’s approval. Which of course is something a wife is expected to endure, but which as a husband Kit finds deeply unjust, so now we have another layer poking at the relationship between doing what’s lawful and doing what’s right. It gave my brain plenty of fodder for analysis, just when I needed it. There are a few quibbles I had with the book by the end, but listing those would feel like pointing out that you don’t really like the floral print on this amazingly well-sprung and comfortable armchair. Sometimes a well-designed structure trumps everything.

“I’m … more wild than tame. If I had to choose between a ballroom and the prow of a fishing boat, I’d take the fishing boat every time.”

And because the author name-checked Penzance once and my brain took the reference and ran with it:

Kit is the very model of a romance hero veteran

He wants to build a pleasure garden that he can feel better in

He has to marry quickly to ensure financial solvency

But debutantes are wary of his rampant alcoholency.

Our Tamsyn is a country girl who cares about her neighborhood

She knows that smuggling earns her more than honest, legal labor would

She needs to buy a manor house to hide her lace and brandy in

Which leaves her little left to spend on Kit’s unending dandyin’

They marry for the money but that’s not the only thing they spend

There’s quite a lot of angsty plot before they reach the happy end

In short when he decides that love there’s really nothing better than

Kit is the very model of a romance hero veteran.

The Help Desk: The odor of loss

Cienna Madrid is off this week; this column was originally published in 2015. Every Friday, Cienna offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

My granddad died in the spring. He left me all of his books. The gesture meant a lot to me. He used to read to me when I was a baby, and I remember spending hours in his study when I was a kid, flipping through his books. So now they're my books. But there's a problem: they stink. My granddad was a heavy smoker and I'm not. His books reek of cigarette smoke. I've looked around online and the solutions for this are complicated and seem like they might not work. Am I a terrible person if I give these books away? Will anyone even take them? They really, really smell bad.

Jim, Renton

Dear Jim,

I empathize. When my grandmother, Berta, died on Christmas Eve a few years ago, my mother inherited the chair she died in and I inherited her death suit: a fuzzy blue robe and dog-hair enhanced red slippers. Everything smelled like ham and stale Easter candy. So loud was the candy-ham stench that cats and men in camouflage named Rufus started showing up asking vague questions, or mewing, with shifty eyes. I took up not bathing just to mask the odor.

Have you considered not bathing? It frees up a lot of time for reading!

Most babies have shit taste in books, so I hesitate to guess what your collection could entail. Still, I suggest going through and choosing one or two that have sentimental value. Carefully pack those books in a drawer with aromatic soaps (or a candy-ham combo), which will help the smoke smell dissipate after a time. Then, organize a party (New Year’s is a fine excuse) and sacrifice the rest of your grandfather’s collection to a roaring bonfire. I know book burnings are still gauche everywhere except church parking lots and the odd Trump rally, but still: donate books in such terrible shape and they’ll end up in the dump anyway. You might as well celebrate in style with friends, family, and a smokestack worthy of your grandfather’s memory.

Kisses,

Cienna

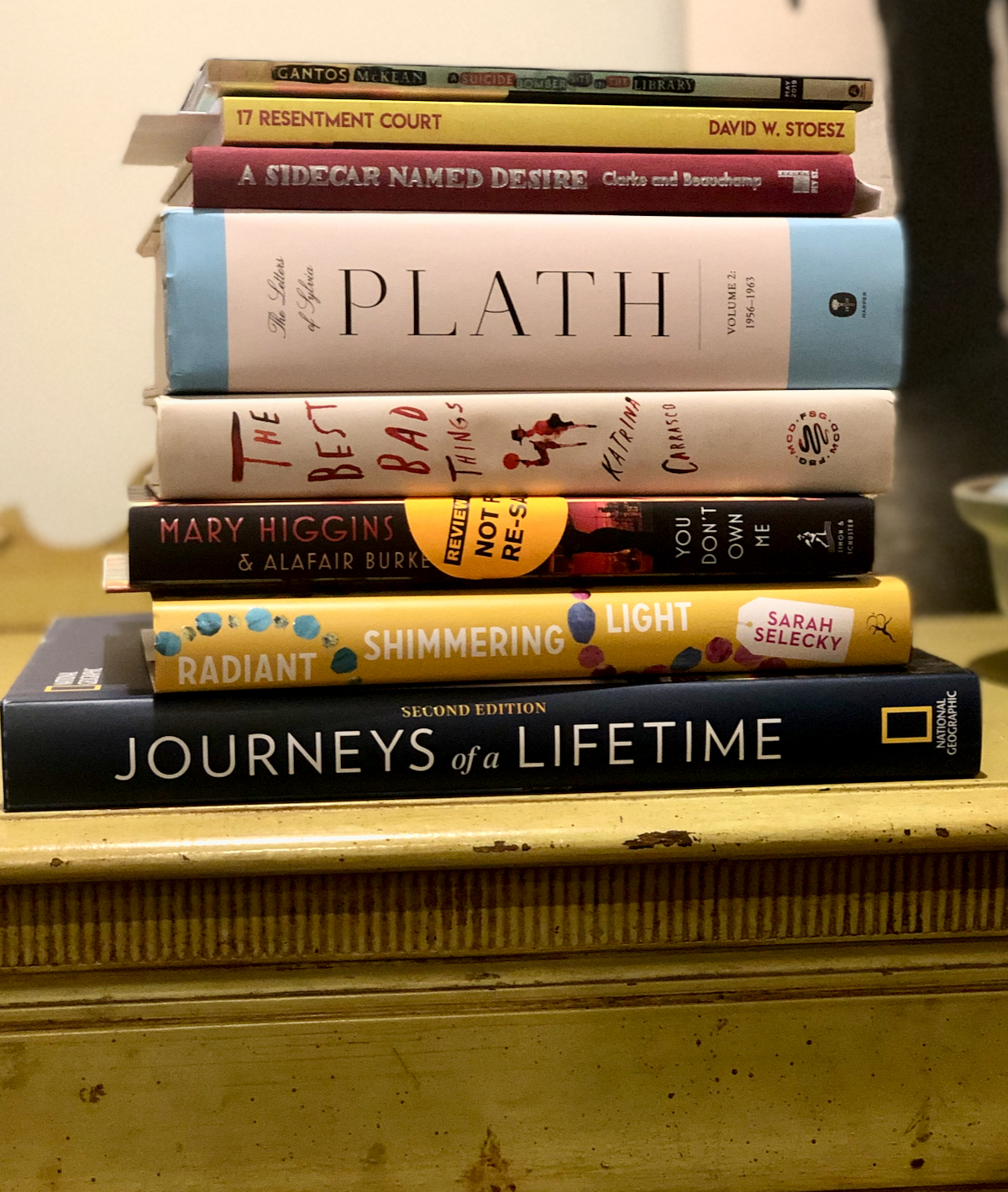

Mail Call for November 1, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Thursday Comics Hangover: All-singing, all-dancing

A panel from Rina Ayuyang's Blame This On the Boogie.

It's a clear sign of the Short Run Comix & Arts Festival's rising fame that Montreal comics publisher Drawn and Quarterly chose the festival for the world premiere of cartoonist Rina Ayuyang's new memoir Blame This On the Boogie. Ayuyang will appear at Short Run on Saturday and she'll be in conversation with Seattle cartoonist Megan Kelso at the Central Library on Sunday at 1 pm. Boogie is the kind of high-profile debut that D&Q could have hosted anywhere, but Boogie is a natural fit for Short Run: it shares an ingenuity and an exuberance with the festival.

Ayuyang, the daughter of Filipino immigrants, grew up in Pittsburgh with a large and boisterous family. Boogie is a coming-of-age story, a story about the challenges and rewards of family, and a tribute to the glamorous and goofy world of dance entertainment — particularly movie musicals and reality dance competitions. Perhaps that last element sounds out of place in a synopsis, but it couldn't feel more right on the page. Thematically and artistically, Boogie is a triumph; it brings the energy and joy of a truly great musical to the comics page.

Ayuyang's colorful, vibrant comics bear no relationship to the darkly cynical autobiographical comics of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Her panels aren't often separated by gutters, and panel after panel clambers onto the page, resulting in a bright parade of color and emotion. With no panel borders, elements from previous panels leak into the story and characters seem to be mingling together without regard for time or space. It feels like a story told by a narrator who is so excited that she jumbles elements of the story together, leaping back and forth through time, but Ayuyang retains total control over every element of her craft. She knows exactly what she's doing.

The book begins with a wide, sweeping look at Ayuyang's suburb from miles in the air. The greens are sketched in with what appear to be colored pencil. Our perspective is closing in on Ayuyang's house, a respectable two-floor middle-class home.

"From afar, it looks perfect," Ayuyang tells us in a caption.

She closes in on the front door. "But if you look closer, things aren't always what they seem."

Then a closeup of the pebbled green glass of the front door. "Beyond this door," Ayuyang warns the reader, "lies a story of dread and woe, despair and sadness."

Turn the page, though, and we see a young Ayuyang playing in a warm and cozy home. Toys are splayed all around her. "I'm kidding," she writes. "It's just a mess. Mostly mine."

The characters in Boogie certainly do confront pain and heartbreak, but the story is a happy one. Ayuyang is a cheerful narrator — even as she describes her addiction to Facebook and the conflict of reality smashing up against the monolith of fantasy, she's inclined to be a positive and generous host.

Boogie is a series of anecdotes that accrue together into something much bigger than the sum of its parts. Not every trick in the book works — a major time jump near the middle of the book feels very abrupt, and it takes the reader a few pages to catch up to all the developments in Ayuyang's life — but every trick is attempted in good faith, with an excitement for the medium that is infectious.

It's hard to convey the precision of a good dance number to comics, and Ayuyang often is forced to relate whole dance routines in one or two wavy lines and a couple of distorted figures. But it's hard to imagine any cartoonist being able to transfer the complexity of a densely choreographed dance number with ink and paper. What Ayuyang fails to report in accuracy, she more than makes up for in enthusiasm. Short Run is where Seattle's youngest and most promising cartoonists go for inspiration, they would be well advised to pick up Boogie and learn at Ayuyang's (dancing) feet. Comics could use a lot more of this color and life and energy.

Short Run's biggest self-described "fanboy" is ready to help guide the festival into the future

Earlier today, we published interviews with Short Run board members Megan Kelso and Mita Mahato.Our final Short Run interviewee of the day, Otts Bolisay, is the newest member of Short Run's board, but his enthusiasm for the organization is palpable.

How did you get involved with the Short Run board of directors?

[Short Run cofounder] Kelly [Froh] invited me last year. I had been a Short Run fanboy for a pretty long time — I had gone to, I think, every single one of their summer school classes. I'd been to the programming that they have around the Festival every year. They brought Anders Nilson in one year to speak at Ada's on Capitol Hill. I hadn't really known his work, but even to hear their introduction, and why they thought he was an interesting artist and why they even bought him out to Seattle was just really great. I didn't know any of that stuff. I'd even volunteered at the festival — I screenprinted shirts and everything. I think all that showed I would actually show up and that I was interested.

Why you in particular? What do you think you bring to it?

You know, it's funny: I actually told Kelly that I didn't think I should be on the board because one of the things that I appreciated about Short Run is it was so very distinctly led by women, and that fact showed up in all sorts of ways that I appreciated in the programming. Just everything about Short Run was welcoming and open and it had really different energy. And I appreciated that and I didn't want to mess that up.

So what did Kelly say in response to that?

She said, "no, it's still women-led because I'm here." And I think she knew my background in communications, working especially with nonprofits — she may have had some of that in mind, and some of my relationships that I've had over the years with communities of color. I've done a lot of social change work, and that might have been something that she was hoping I could also bring to the board.

So what have you been doing? What have you been up to?

Well, leading up to the festival, we were just talking about the kinds of programming we wanted, who we could get, who might be a good person to do [onstage] interviews and things like that. And as we get closer, it's more festival business, just the day-to-day of the organization: making sure that there's money, that we don't have to scramble for anything, that we are able to pay people.

I send out the few emails that the organization sends out — reminding people that the festival's coming up, or contacting all the exhibitors with the instructions for Fisher Pavillion, and updating the website.

And as a self described Short Run fanboy, what are you looking forward to in this year's festival?

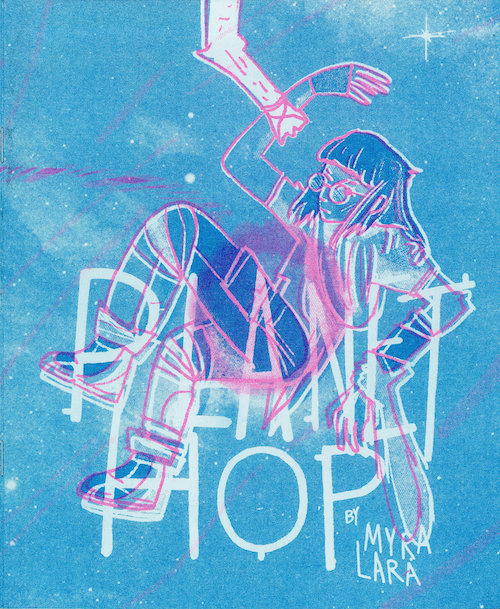

A coworker of mine sent me an illustration that somebody named Myra Lara, did and it was really cool. And I checked out Myra's website and I realized Myra is one of our exhibitors, and she's also local. Myra is one of the people I'm really looking forward to seeing. I'm also excited for something called Free Ass. Mag. Anders Nilsen is going to be back. i think he's going to have the second part of Tongues with him. I bought the first part last year and I loved it. I'm looking forward to picking that up.

And then I'm excited about yəhaw̓, an indigenous regional indigenous creative group. They've got a bunch of events over the course of the next year, but they're going to be tabling as well. I'm super excited to see what they have.