Megan Kelso is helping Short Run find the ground between "institution" and "crazy young upstart"

Anyone who has spent any amount of time reading Seattle comics knows the name Megan Kelso. Kelso has long been a passionate advocate of the Seattle comics scene, but this year is her first as a full-time member of the board of the Short Run Comix and Arts Festival. We talked about the board's work this year of institutionalizing Short Run without losing any of the special sauce that makes it so great. (Read our interview with Short Run chair Mita Mahato here.)

How did you get involved with the Short Run board of directors?

I met Kelly right after I moved back to Seattle after being away in New York for years. I moved back in 2007 and I met Kelly soon after that at comics events, and then Short Run started up soon after that. I remember her contacting me before the first Short Run and saying something like, "please support us by getting a table — we want as many longtime Seattle cartoonists to participate as possible."

And I was just so thrilled that like a thing like Short Run was starting in Seattle, because for all the comics we have going on here, there had never been much of a show. So I was really enthusiastic from the very beginning. I didn't have a table every single year, but I tried to be involved in some way every year.

To be honest, I wasn't like a super-involved volunteer. I would, you know, put up posters, or sometimes I would host artists who were visiting from out of town. But I always tried to keep my hand in.

And then I also have this other relationship with Kelly, because she looks after elderly people — she's a companion to them, and keeps them company. And she worked for my mom for years. So we, we grew kind of close through that, which had nothing to do with Short Run, but I think we developed this whole working relationship because of that. And in a way I feel like that's partly why she invited me on the board — she got to know me in this other way that showed I was a reliable person in a non-comics context. Then I had more time after my mom died, and Kelly knew that, so that's when she swooped in and asked me to become a more involved Short Run helper.

I was thrilled because I had been keeping my distance a little bit. I just didn't have the time for a few years, because things were really heavy going with my mom. But then my time freed up.

I think I'm the oldest person on the board. And I think that's partly why I'm there too, is I'm a sort of connection to like the comic scene of years past.

So what has it been like, putting the show together from your perspective?

We started meeting in January or February, I think. And, you know, Kelly was really frank with us from the very beginning that she was going to need more help from the board than years past because she didn't have her partner, Eroyn. They kind of invented Short Run out of whole cloth, and they had a lot of it in their heads. So a lot of what Kelly had to do was put more down on paper and put more out for us to do, because she knew she couldn't do it alone.

So I think a lot of this year has been us helping Kelly download everything about Short Run that's been in her brain. I'm getting it more documented so that we can take a lot of it on.

It's an interesting process at the beginning of the year. It's super pie-in-the-sky — we're talking about our hopes and dreams for the next year for the show. And then as time marches on, things just get much more practical: "who's going to pick up this artist at the airport, and who's going to follow up with that person to see if we can get some publicity?"

So, yeah. I have a much better picture now about the yearly cycle of Short Run.

There's been this thread running through the year that we want to make the show more appealing to families with children. We also want to include more people of color both as artists but also as people who help with the festival and, ultimately, work on the board. We've been talking a lot about opening up Short Run to be more than just the traditional comics community that we've had in Seattle over the years — a community which is awesome and who we love. But we also want to open up Short Run to a wider world of people, especially since Seattle's growing so much right now.

Is there anything in particular that you're especially looking forward to this year that you want our readers to know about?

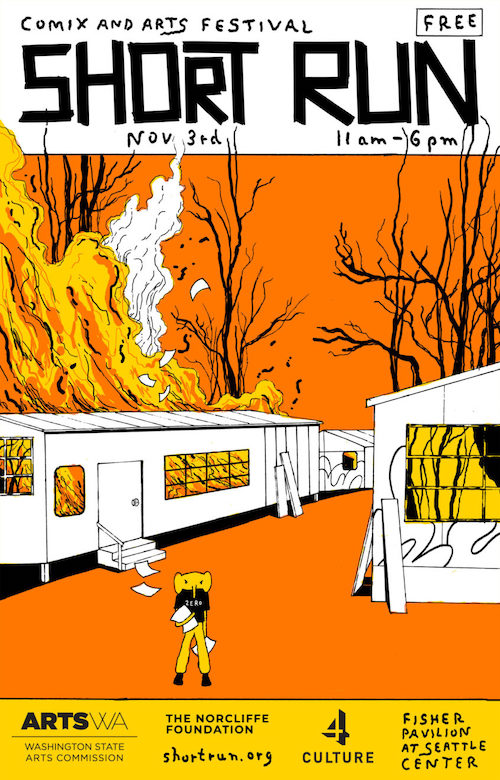

I'm really excited about the artist Anna Haifisch, who drew our poster. I wasn't familiar with her work until Kelly introduced us to it. I think it's one of the coolest posters we've ever had — we've all talked about how it feels timely, like we do feel like the world is on fire right now, and that's kind of been a sort of running theme as we've been planning. So I'm really looking forward to meeting her and seeing more of her work.

And then the other one that I'm, excited about is Rina Ayuyang. I'm actually going to be interviewing her onstage, and I'm excited about it because we've been cartoonist friends-slash-colleagues for years and we've always had a lot to talk about. So I think it'll be kind of really fun for us to do that in this public way. She has this awesome new book from Drawn and Quarterly called Blame This On the Boogie which is all about her obsession with dance movies and dance reality shows. It's just this crazy kind of all-over-the-map book, and I really love it.

Is there anything else that you think that our readers should know before before Short Run really gets underway?

One of the things that I've been thinking about and talking to Kelly about is that this is Short Run's eighth year, and I was imagining a teenager who loves Short Run, who kind of grew up going to Short Run. For that person, Short Run is this institution. Even though we still think of ourselves as this kind of crazy upstart project, I think we're starting to be viewed from the outside as more of an institution. That's an interesting place to be — you have to reconcile your inner feelings of "oh, we're just putting on this crazy show" with the expectations that people have because it's been around for a while now.

Talking with Mita Mahato about Short Run, the "perfect model of a festival"

Back in August, I interviewed Short Run Festival cofounder Eroyn Franklin about her decision to step down from leadership of the small press, zine, and comics expo. With this year's Short Run Comix and Arts Festival around the corner — events are happening all week long, with the big show arriving this Saturday — I wanted to interview current Short Run leadership about what to expect at this year's festival and in the years ahead.

Aside from Franklin and Short Run cofounder Kelly Froh, Mita Mahato is probably the local cartoonist most associated with the festival. Mahato, who makes beautiful cut-paper comics that are unlike anything anyone else is doing, has slowly become an indispensable part of Short Run.

We'll be running more interviews with Short Run board members throughout the day, so check back for more previews of the festival this aternoon.

When did you join the Short Run board?

I was brought onto the board back in 2014 when when Kelly and Eroyn applied for nonprofit status for Short Run. I had been exhibiting since the second year of Short Run. For me, coming into the comic scene in Seattle, it was just such an exciting community. There's so much support and so much excitement about everybody's projects and I knew that Short Run was a big part of that.

So when Kelly and Eroyn started talking about making it a fully fledged organization that's largely women-run, that was just really exciting to me. So I became a part of the board and served as secretary. When Eroyn left, Kelly and I talked about whether it made sense for me to move into the role of chair. And that's the role that I've been in this past year.

A few months ago, I did a sort of exit interview with Eroyn about leaving her role at the organization. So could you talk a little bit about what it's been like working on Short Run without her for the first time?

I think one of the big things is that we collectively decided that we don't want to change. Kelly and Eroyn developed the perfect model for a festival back before it was even an organization in 2011, and so a lot of what we're doing as a board is trying to maintain the vision of that.

We want to keep Short Run a place for voices and perspectives. And when I say "voices and perspectives," I mean in aesthetics as well as personal backgrounds that we don't see in mainstream or widely publicized comics. And so a lot of what we've been doing since Eroyn has left is trying to kind of cultivate that vision, especially as the organization is growing. We have our opportunity to bring in bigger names, but we also want to make sure that we're finding ways for new voices and underrepresented communities to have inroads and a platform at Short Run.

Can you talk a little bit about what you're looking forward to at this year's festival? Bearing in mind, of course, that the exhibitors are all your babies and you love them all equally.

What I'm really excited about is we're sponsoring a teen table at this year's fest. We're going to have teens from Foundry 10 and the Henry Teen Art Collective sharing a table and showcasing their projects. It's such an exciting opportunity to have them share their work with other exhibitors to get some informal mentoring.

And something that I'm really excited about, too, is that it gives the opportunity for the teens and kids who are coming to the show to see that this is something they can do, too. We're trying to expand our education programming and reach out to the next generation of comics- and zine-makers, so we're really excited about the teens being there.

And you specifically are debuting a new book at the festival, right?

I am, which is the main thing that I'm spending my time on today. I conceived of it initially as a sequel to my book, Sea, which I made in 2015 and which was very much about honoring the silence of the seas and trying to get out of the way we communicate as humans by thinking about how whales communicate .

I was, as I think many of us were, deeply affected by the story of the Orca, J50 the Orca baby, and her mother's grieving. I was trying to figure out what my response was to this. And so it's a book similar to Sea but instead of silence it's acknowledging the noise and the undeniable presence of humans when it comes to the oceans. It's called Lullaby and it is one of the saddest things that I've worked on.

I told you over the summer that John Green was bringing a new, sideways book format to America this fall, and now the New York Times has a closer look at the format — with animated GIFs!

Ms. Strauss-Gabel began her mission to import flipbacks to America this year, when she received Dutch editions of two of Mr. Green’s novels. She was startled by their size and ingenious design — the spine operates like a hinge that swings open, making it easier to turn the pages.

The only problem with the flipback format: these books cost $12 each. I guess the "mini" that they're using to describe the format doesn't refer to the price. I was hoping these books would be more like mass-market paperbacks in price, meaning less than ten bucks. Twelve dollars is just enough to push them out of impulse buy territory.

The pratfall of Rome

Published October 30, 2018, at 12:01pm

Sierra Nelson has been writing and reading in Seattle for decades. Her debut poetry collection is out this week. What took so long?

The Skaters

The ice was always cracking

towards shore.

In its low thundering mist

we felt our own slicktreacheries accumulating. We skated ‘til dark,

dodging in and out

of the groaning

weather, shivering forwardlike a train shuttering forever towards the horizon.

And only for a moment did we hope

for the ice below us to peel back, for

the surface to rearrange itself beneath us.Then — we were falling, glamorously

into a black — splash of water.We couldn’t wait to be famous,

or simply to leave,to look back

upon it — our miniature landscape,a diorama of who we’d once been,

where we’d placed our cold

red hands and

let out

our hot and hopeful breath.

Mail Call for October 29, 201

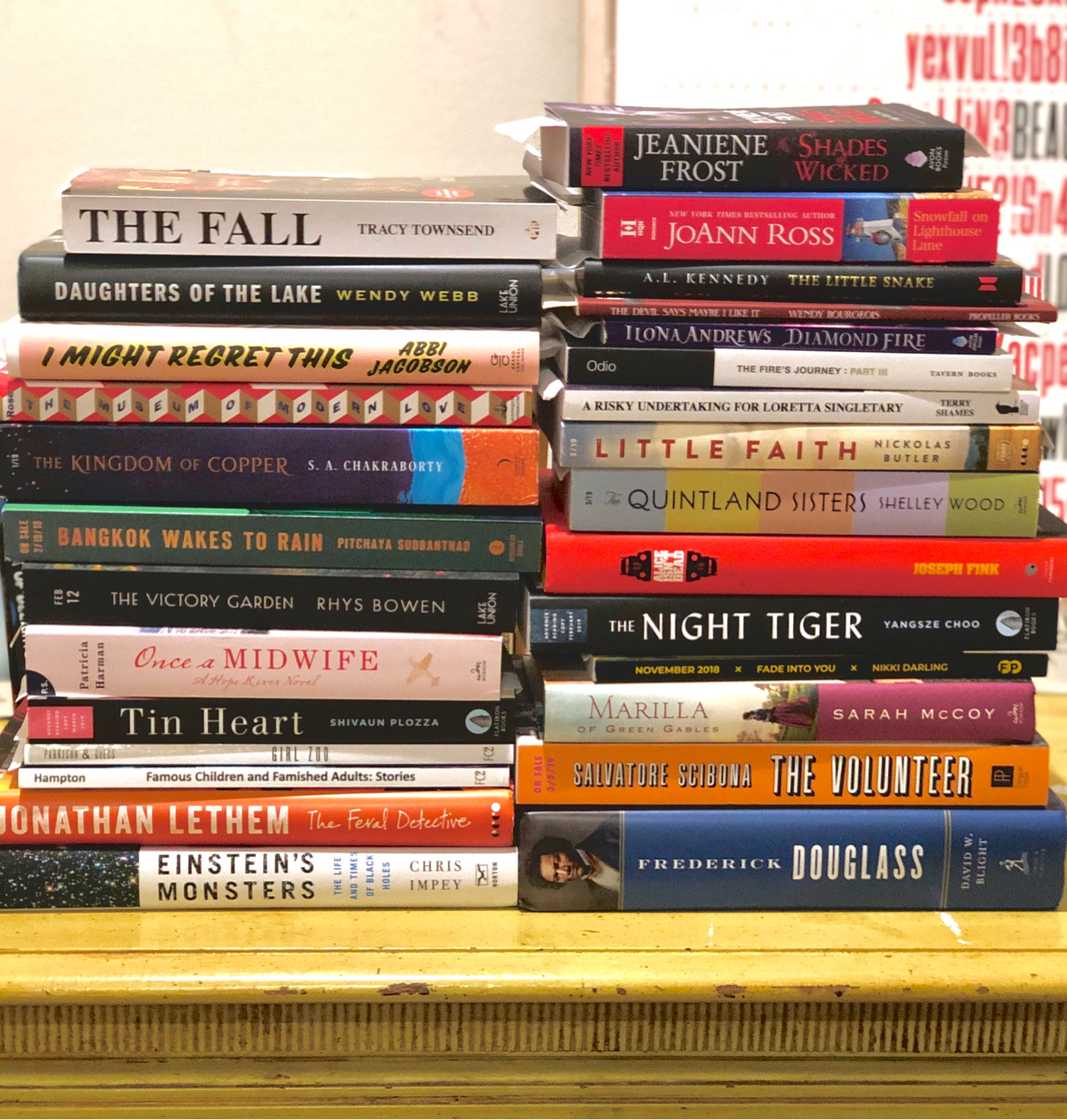

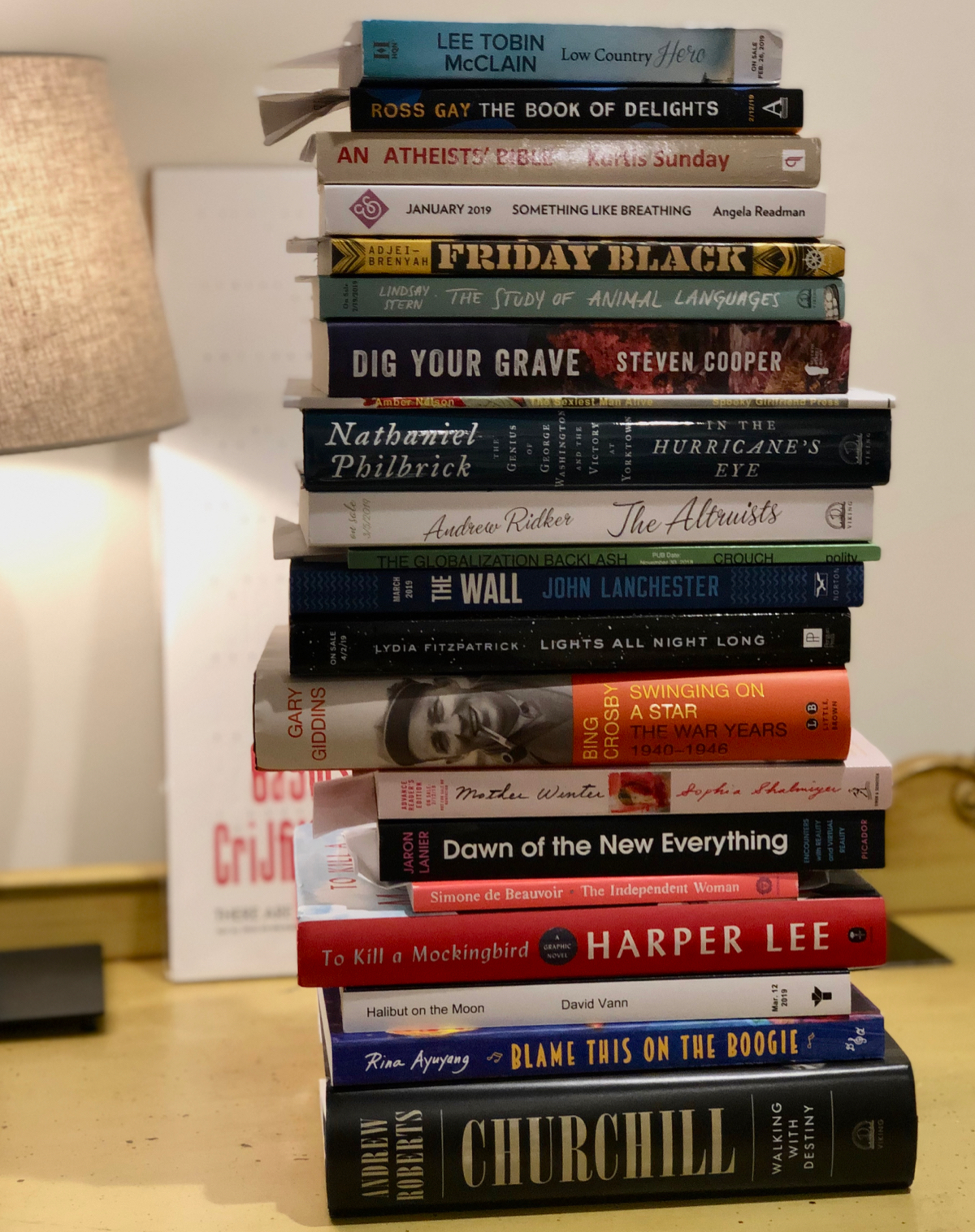

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

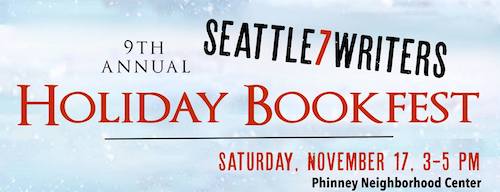

Mark your calendar for the last (sob!) Seattle7Writers Holiday Bookfest

This year’s event is the ninth annual and final Holiday Bookfest — so mark your calendar now for Saturday, November 17, 3 to 5 p.m. Seattle7Writers announced earlier this year that it will retire its nonprofit status in July 2019 after serving the community for 10 years. Don’t panic; the amazing community they’ve built isn’t going anywhere. But we recommend taking every chance you can to celebrate them between now and July.

The event features 26 local authors mingling and chatting with guests, as well as readings from a select few and a performance by Seattle7Writers' house band, The Rejections. For a full list of participants and performers, check out our sponsorship page.

And thank you, Seattle7Writers, for offering so much support as a sponsor and an ally. We'll see you in November!

Sponsors like Seattle7Writers make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you can sponsor us, too? We're sold out through January 2019, and we haven't released the next round of slots — which means this is a great chance to reserve dates for February through July before they sell. Just send us a note at sponsor@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from October 29th - November 4th

Monday, October 29: People Like Us Reading

Sayu Bhojwani is a political scientist whose book People Like Us is subtitled The New Wave of Candidates Knocking at Democracy’s Door. Tonight, she'll be interviewed by UW poli-sci professor Sophia Jordán Wallace about candidates of color and women candidates who are breaking the stranglehold that white men have on American politics. Rainier Arts Center, 3515 S. Alaska St, 652-4255. http://townhallseattle.org, 6 pm, $5.

Tuesday, October 30: Dungeons and Dragons Art and Arcana Reading

This is a reading for a big and beautiful art book that serves as a visual history of Dungeons and Dragons. There's artwork and photographs and rarities and all sorts of D&D history crammed between the covers, which the publisher refers to as "the most comprehensive collection of D&D imagery ever assembled."

University Lutheran Church, 1604 NE 50th St, https://townhallseattle.org, 7:30 pm, $5.

Wednesday, October 31: The Meaning of Blood Reading

Chuck Caruso's murder-and-sex-packed collection of short stories veers from crime to westerns to horror and back again. This is a great way to spend a Halloween if you don't want to dodge kids in costumes or chronically drunk college students on the streets of the city. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 6 pm, free.Thursday, November 1: Instruments of the True Measure Reading

Phenomenal Seattle poet Laura Da' debuts her latest collection of poetry, with the help of local poets Sasha LaPointe and Casandra López. Instruments of the True Measure is about identity and what it means to be from a place and maps. We'll be hearing a lot more from and about Da' here on the Seattle Review of Books as the month goes on. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Friday, November 2: The Lachrymose Report

Sierra Nelson's debut collection of poems, the debut title from Poetry Northwest's new publishing arm, has been described by many (including me) as "long-awaited" for so long that it's hard to believe it's finally here. Nelson, a beloved Seattle poet, has somehow never published a full-length book before, so this is a very special night. Nii Modo Art Gallery, 4453 Stone Way North, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.

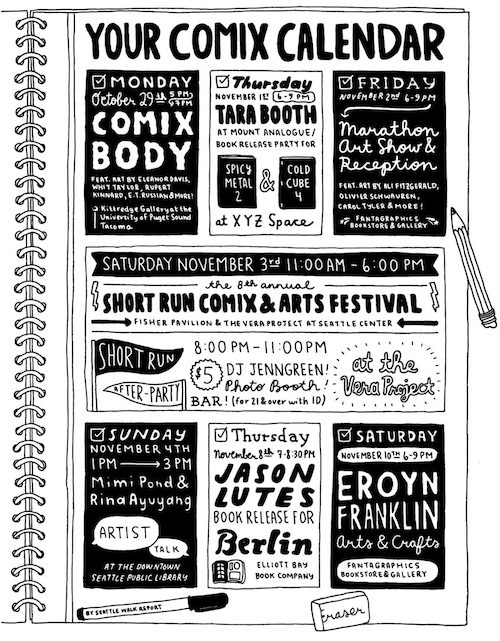

Saturday, November 3: Short Run Comix and Arts Festival

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Seattle Center, http://shortrun.org/, 11am to 6 pm, free.Sunday, November 4: Vicinity/Memoryall Reading

The former owners of Open Books, Christine Deavel and John Marshall, read from a new play they've been working on. The play is about two people trying to find a memorial. This reading will also be accompanied by a short film. Hugo House, 1634 11th Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org, 7 pm, free.Event of the Week: Everybody get ready for Short Run!

The Short Run Comix and Arts Festival has become the kind of joyous and surprising community event that Seattle's literary scene has always wanted. It's a book festival, but it's more than a book festival. It's a comic convention, but it's more than a comics convention. It's an art show, but it's more than an art show. It's a place for everyone to get together and check out what they've been working on. This week is full of Short Run events. Here's a little schedule, but you can learn more on their website.

- Tonight at the Kittredge Gallery at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Short Run artists including Eleanor Davis, E.T. Russian, Joe Garber, Robyn Jordan, Kelly Froh, Krystal DiFronzo, and Ann Xu will be onhand to celebrate the closing of a show about comics and the corporeal titled COMIX BODY: sensitive skin, vulnerable meat.

- On Thursday, the XYZ Gallery hosts a publication launch party from cartoonist Tara Booth.

- Friday at the Fantagraphics Bookstore & Gallery, join the reception for a new art show featuring Ali Fitzgerald, Mimi Pond, Carol Tyler, Anna Haifisch, Olivier Schwauren, Antoine Maillard, Melek Zertal, Rina Ayuyang, Eroyn Franklin, and November Garcia.

- Saturday night after the big show (about which more later,) there's a Short Run Afterparty featuring DJ Jenngreen, kinetic sculptures, and more. This is at the Vera Project and it's 5 bucks.

- And on Sunday at the Seattle Public Library downtown, Mimi Pond and Rina Ayuyang discuss their latest comics publications. Ayuyang is sharing the world premiere of her Drawn & Quarterly title, Blame it on the Boogie, with Short Run.

But of course the main event at Short Run will always be the book expo proper, which happens at the Fisher Pavilion from 11 to 6 on Saturday and is free.

Every year, the expo gets a little bigger and the programming gets a little more robust. This year's features storytime for kids featuring Jessixa Bagley, a literary reading hosted by Colleen Louise Barry, a comics workshop for teens from David Lasky, a postcard screen printing workshop, an animation tent, and a virtual reality demonstration.

But, listen: here's the most important part of Short Run. There's a book at this book expo that you will fall in love with. It will feel like it was made just for you. I don't know what it is. You won't know what it is until you see it. But here's how you find it: go to the show. Walk up and down the aisles. Do two circuits. Look at all the booths, talk to the artists, and take in the sights. Something will call to you. Pick it up. Smell it. Look at it. Buy it. Take it home. It will be the book for you. You can find it. I know you can.

Seattle Center, http://shortrun.org/, 11am to 6 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for October 28, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

How to Burn a Book

Susan Orlean sets Fahrenheit 451 ablaze.

I struck the first match and it broke, so I struck a second, which spat out a little tongue of flame. I touched the burning match to the cover of the book, which was decorated with a picture of a matchbook. The flame moved like a bead of water from the tip of the match to the corner of the cover. Then it oozed. It traveled up the cover almost as if it were rolling it up, like a carpet, but as it rolled, the cover disappeared. Then each page inside the book caught fire. The fire first appeared on a page as a decorative orange edge with black fringe. Then, in an instant, the orange edge and the black fringe spread across the whole page, and then the page was gone—a nearly instantaneous combustion—and the entire book was eaten up in a few seconds. It happened so fast that it was as if the book had exploded; the book was there and then in a blink it was gone and meanwhile the day was still warm, the sky still blue.

Saving the World, One Meaningless Buzzword at a Time

Michael Hobbes sets “corporate social responsibility” ablaze. This is very good — unraveling an ideology that has been carefully built up by for-profits and nonprofits both, in a shell game of respectability and money.

Samantha asks if you offer certification, a stamp her company can put on its website declaring that it complies with human rights.

"We prefer to work behind the scenes," you say, kicking off a spiel that has started to sound less natural lately as you have delivered it more. "Complying with human rights is complicated. It's relevant to all your operations, all your suppliers, all your relationships with governments. We recommend that companies do this privately, and focus on delivering real improvements to their employees and their customers, before they communicate it publicly."

"Right," she says. "But we can still put your name on our website, right?"

"Well of course," you say

Why We've Always Needed Fantastic Maps

My grandfather was an adventurer trapped in very suburban home in Jackson, Mississippi. He dreamed of planting saplings until a vast forest overgrew the land he owned, of free-diving for pearls in the Indian Ocean, of being lost in the desert of the American West. When macular degeneration blotched his vision and dementia blurred his reality, he talked with wonder and longing about the strange maps that floated between his eyes and the world.

Here’s Lev Grossman on the allure of maps of imaginary places, especially for those who long for more wonder than daily life readily yields.

One's eyes quickly learned to hungrily parse a newly acquired map: the long spindly corridors, the secret doors, the treacherous mazes, the crooked borders of unworked stone, the grand hall where the massive showdown melee would happen, the over-elaborate legend listing symbols for urns, statues, pillars, traps, treasure chests and altars to nameless gods. These maps promised extremes of excitement and pleasure, though players weren't actually supposed to see the maps, strictly speaking. D&D wasn't a board game: the map was a holy mystery, concealed during gameplay behind a makeshift cardboard screen. The Dungeonmaster would instead painstakingly describe a player's slow, bloody progress across it. Denied the aerial omniscience of a map, one was in the position, increasingly inconceivable in the age of Google Maps, of being lost on a darkling plain, stumbling towards an unseen goal, with only words to steer by.

On Likability

Why do we want so, so badly to be liked? Human nature, sure, but human nurture, too. And who defines what’s likeable and what’s not? And who benefits? Hmm. Maybe Lacy M. Johnson knows.

As a woman, I have been raised to be nurturing, to care for others feelings’ and wellbeing often at the expense of my own. I have been taught that to be liked is to be good. But I have noticed that certain men are allowed to be any way they want. They get to be nuanced and complex. Adventurous and reclusive. They can say anything, do anything, disregard rules and social norms, break laws, commit treason, rob us blind, and nothing is held against them. A white man, in particular, can be an abuser, a rapist, a pedophile, a kidnapper of children, can commit genocide or do nothing notable or interesting at all and we are expected to hang on his every word as if it is a gift to the world. Likability doesn’t even enter the conversation.

Ask Polly: I’m Sick of Being Unhappy and Alone!

Heather Havrilesky, in unintentional counterpoint to the Johnson essay linked above, brilliantly riffs on a 15-minute Yes video to provide a master course in being human.

Sure, you’ll become a joke to someone somewhere, eventually, just for doing what you love. Someone will say, “Holy shit, why don’t they stop touring?” And someone else will say, “And they’re still recording live albums, too!” How many live albums by Yes does any one human need?

But that’s not the takeaway here. The takeaway is PUT ON YOUR SATIN MCCALL’S PATTERN BLOUSE AND ROCK IT OUT.

Whatcha Reading, Priscilla Long?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas on who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Priscilla Long is a Seattle-based writer of poetry, creative nonfiction, science, fiction, and history, and a long-time independent teacher of writing (and yet, somehow, this list undersells her). The second edition of her wonderful The Writer's Portable Mentor: a Guide to Art, Craft, and the Writing Life is just being released by the University of New Mexico Press. She'll be appearing tonight at 7:00 pm to talk about this at the Elliott Bay Book Company.

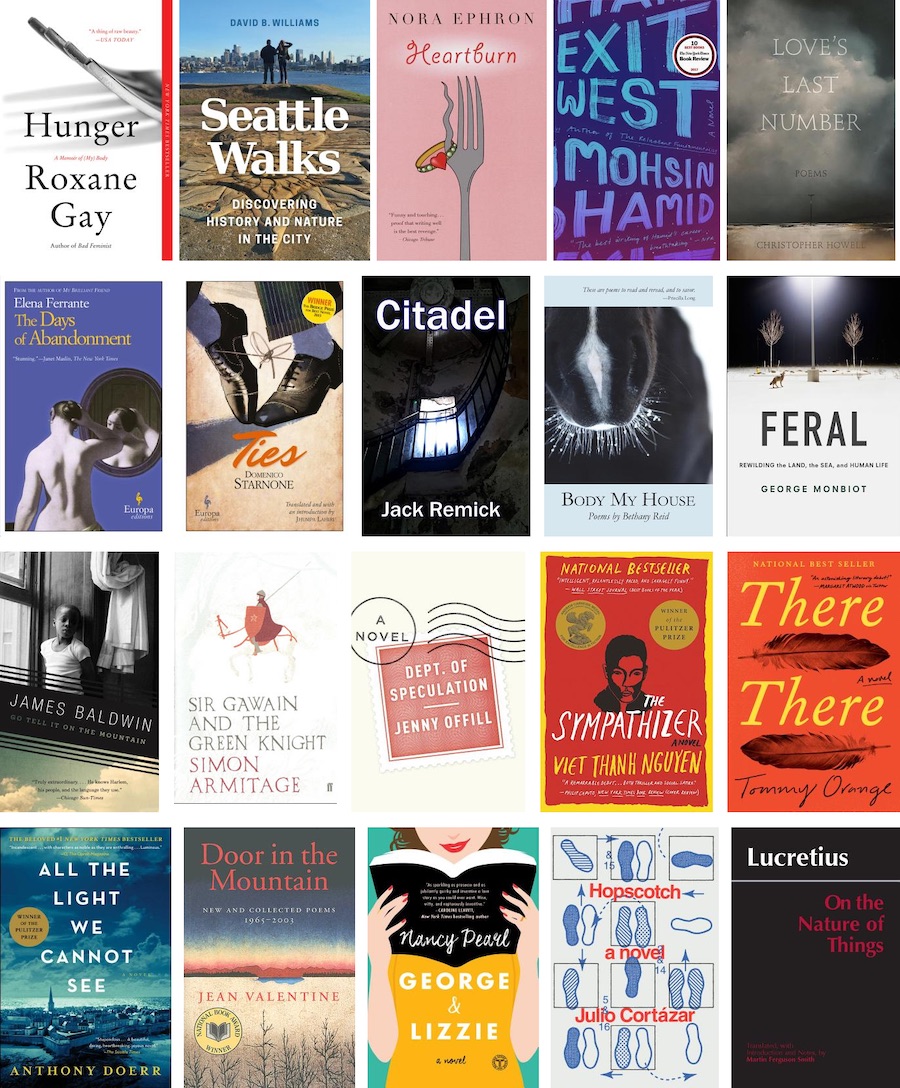

What are you reading now?

I read two, four, five books at once. I set the limit at five. I mean, really. Okay, so, now I am reading Roxane Gay's Hunger. Wow. Talk about #MeToo. And what a fantastic writer. What insight she brings to the subject of the body. What sentences she brings to the page. For poetry, Christopher Howell's Love's Last Number. Do we need to say one more thing about Howell's great poetry? I am still reading David B. Williams's Seattle Walks, walks that elucidate our history and geography, and believe it or not, I have walked all 17 walks. I will walk a few again. I thought I knew Seattle but learned something new on every walk. I am reading Exit West by Mohsin Hamid. A moving love story set in the violence and dislocation of the world as we know it.

What did you read last?

I've read a set of three novels about breakups, each one totally different and each one a great read. (No, I am not breaking up with anyone or anything.) Start with Heartburn by Nora Ephron, in which the narrator provides recipes, including that of the lime pie she puts in the face of her soon-to-be-former husband. Then The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante. A beautiful thing. And third, Ties by Domenico Starnone, translated from the Italian by Jhumpa Lahiri. This family drama brings the word dysfunctional to new depths. I've just read my friend Jack Remick's Citadel, a powerful apocalyptic novel of the future in which women have had enough of the violence of men and have kicked them out (of the world). And then I read my friend Bethany Reid's new book of poems, Body My House (full disclosure: I wrote the foreword). They are wicked and delightful. For science, Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life by George Monbiot. A fascinating rethinking of ecological restoration. Finally I must mention The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen. A great work of literature, if you ask me. The language! The story of three friends and the ways they get caught up in the long aftermath of the Vietnam War.

What are you reading next?

Oh my gosh. There There by Tommy Orange. And to complete the set on the dislocations of breaking up, Department of Speculation by Jenny Offill. I have yet to read All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr and it is sitting there on the pile, waiting, waiting. I am rereading James Baldwin; Go Tell It on the Mountain is next. I love to read one very old book every year. Last year it was Sir Gawain and the Green Knight translated from Middle English by Simon Armitage. This year I can't decide. On the Nature of Things by Lucretius? Maybe. Sitting there winking at me is Hopscotch by Julio Cortazar, a writer I adore. Also winking: 2666: A Novel by Roberto Bolaño, another writer I adore. Next will be George and Lizzie by Nancy Pearl. For poetry I have waiting for me Door in the Mountain: New and Collected Poems by Jean Valentine. I will stop here. I worry about the pile falling on my head and knocking me unconscious.

The Help Desk: For the love of all that's holy, give me some good news

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I keep wanting to write and ask you for your take on the latest political scandal, but every day it's a new one (or four), and then no matter what happens is blamed on the people I vote for by people who have agendas that serve their pocketbooks. I guess I'm feeling a bit overwhelmed by everything, and need a recentering. Got any good poems or art or, sorry book review website people, music that pulls you out of a deep years-long depressive funk?

Desperate, Madrona

Dear Desperate,

First of all, you are not alone. Second, you have come to the right place. As an unlicensed therapist who keeps irregular office hours on a Metro bus, I have a few thoughts on misery – the potent combination of helplessness and hopelessness – and its antidote, hope. Some of my therapies are unconventional but that is because I am not owned by Big Pharma or constrained by the chains of science.

First, I recommend you go to the mall and befriend a baby. People like to chitter "children are our future" but they also make great therapy pets and in my experience, most mall mothers are willing to trade a few minutes of supervised baby time for a 20oz Orange Julius. Once you have your therapy baby on your lap, begin a game I like to call "Kisses for Breakfast," wherein you look deep into its baby eyes and ask it if it would like kisses for breakfast. (Don't wait for it to answer – babies cannot give consent, which is part of what makes them ideal therapy pets.) Proceed to give it lots of little kisses all over its soft baby cheeks. Then repeat. For fifteen minutes, you will forget how fucked the world is and the baby will likely enjoy itself until it realizes it would like something other than kisses for breakfast.

If human babies repulse you, that is okay. Therapy spiders are also a viable option and – lucky for you! – fall is the ideal time to harvest them. Therapy spiders are great for travel, as they are quiet, compact, and you do not need to register them with your host airline. I rarely leave the house without a pocketful anymore – when I encounter someone in public who is in desperate need of therapy, I can reach into my pocket and throw a spider at them.

As for books, I know I've mentioned Rebecca Solnit's Hope in the Dark in this column but I'll do it again. Solnit makes a measured case for what can be gained when you embrace hope over helplessness. I also recommend reading (or re-reading) Shel Silverstein – especially his poetry and the book The Giving Tree. If you haven't read Silverstein as an adult, his intelligence, humor, and the unexpected emotional complexity of his stories will delight you.

I also recommend that you reevaluate your relationship with the media you consume. This article about the toxic effects of news didn't convince me abstain from reading it each day but it did make me more aware of what I was consuming and how I was processing it. In addition, you might want to start your day by reading the New York Times's good news briefings.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Marcus Harrison Green

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday, October 15: Emerald Reflections 2

At Third Place Books Seward Park on Thursday night, former South Seattle Emerald editor Marcus Harrison Green, who now writes for the Seattle Times, presents the second anthology of writing from the Emerald, Emerald Reflections 2. It’s a celebration of all things south Seattle, by the only site that regularly reports on Seattle’s most diverse neighborhoods.

Readers include Green, Tiffani Jones, Rollie Williams, Nakeya Isabell, and many more. If you’re a Seattleite and your media diet doesn’t include the Emerald, you’re missing out on some vital voices.

Third Place Books Seward Park, 5041 Wilson Ave S, 474-2200, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Criminal Fiction: Fog city noir

Every month, Daneet Steffens uncovers the latest goings on in mystery, suspense, and crime fiction. See previous columns on the Criminal Fiction archive page

Reading around: new titles on the crime fiction scene

Murder most foul slimes its way through The Way of All Flesh by Ambrose Parry (Canongate), the author’s name a pseudonym for the crafty collaboration between husband-and-wife team Marisa Haetzman, an anaesthetist with an MA in the History of Medicine, and Christopher Brookmyre, author of multiple darkly humorous thrillers. The 19th-century-Edinburgh setting allows for plenty of grisly medicinal gore but also showcases a city vibrantly rich in the burgeoning fields of anaesthetics and photography, as well as ongoing religious transformations. Shimmering with lovingly-rendered historical details — watch for the conversation between a lady and her maid regarding a new novel, Jane Eyre by one Currer Bell, and the friendly neighbourhood druggist busy experimenting with fizzy lemon sherbert concoctions in his downtime – the novel more than holds its own as a compelling and twisted mystery as well.

A family of “soothmoothers” newly-relocated from London to Shetland who are getting the local cold shoulder, and a chaotic neighboring family with a young nanny are just two of the domestic scenarios looming large in Wild Fire by Ann Cleeves (Minotaur). Detective Inspector Jimmy Perez, his loyal sidekick Sandy, and Perez’ colleague-turned-maybe-girlfriend Willow — who also happens to be his Senior Investigating Officer — tackle the suspicious death of a woman, beset on every side — as befitting a tiny, remote, tightknit community – with gossip, lore, and whispers of long-standing feuds and secrets. Partly inspired by Cleeves’ 70s-era residency on Shetland’s Fair Isle, the series’ final book includes a peak-a-boo cameo of the author in a canny and stirring farewell.

Erica Wright’s Kat Stone, just three years out from under the dangerous and suffocating work she did as an undercover cop, is making fresh inroads in New York City as a private investigator. In The Blue Kingfisher (Polis), a new case falls into her domain when she finds her apartment building’s superintendent very much DOA at the Jeffrey’s Hook Lighthouse in Fort Washington Park. A motley cast of colorful characters — including a hallucination-inducing jellyfish and a surprisingly non-carnivorous shark – and Stone’s super-snarky observations, gift Wright’s third novel with substance, entertainment, and chills-a-plenty, as Stone navigates murder on her doorstep as well as the threatening machinations of a wily drug lord.

Catriona McPherson’s new standalone thriller Go to My Grave (Minotaur) features a hulking coastal estate house, newly-decorated to the gills to attract high-end clients for parties, weddings, and indulgent weekends. As the book opens, manager Donna Weaver is celebrating the fact that she’s scored bigtime with a brash group of friends and siblings celebrating a special anniversary. As creepy and unexplained impositions begin to infect the weekend festivities, McPherson, also the author of the cosy and cheeky Dandy Gilver series, deftly infuses dabs of humor within the darker horrors: she’s particularly adept when it comes to the fraught emotional baggage and dagger-sharp verbal cuts that long-time acquaintances can wage against each other – particularly when they are all apparently harboring an old, scary, and deeply-held secret.

The Quintessential Interview: Valentina Giambanco

Murder most unlikely comes to the tiny town of Ludlow, Washington, in Sweet After Death by Valentina Giambanco (Quercus). In light of the underfunded law enforcement infrastructure in the area, Seattle homicide detective Alice Madison is dispatched to investigate with her colleagues DS Kevin Brown and CSI Amy Sorensen. There’s all the palpable tensions a small community generates – particularly between the townspeople and the off-grid locals – as well as genuinely explosive secrets and a landscape that just won’t quit. Plus, Madison’s own hefty emotional baggage trucks along for the ride. With a parallel career in film-editing, Giambanco has an ear for dialogue, an eye for heady visuals, and an unmissable ability for setting a page-turning pace.

What or who are your top five writing inspirations?

- Human relationships – always a never-ending source of surprising material.

- Good people doing bad things and bad people doing good things.

- Outsiders and all those who don’t quite fit in.

- The small details of everyday life – you’re sitting in the bus and you see someone doing something and go, “Oh yeah, I’m stealing that tiny gesture.”

- Wilderness and the way that, in the wild, human beings reveal who they truly are.

Top five places to write?

- The window seat on a train.

- The aisle seat on a plane.

- A particular bench in my local park.

- The New York City library on Fifth Avenue, in the lovely reading room with the brass lamps.

- My dining table, looking out of the window at the trees.

Top five favorite authors?

Only five? Okay, this is today’s list…Raymond Chandler, Louise Penny, Thomas Harris, Rory Clements, Karin Slaughter.

Top five tunes to write to?

I work better with soundtracks – no words, a lot of atmosphere. These are the five I always return to: American Beauty and The Horse Whisperer by Thomas Newman, Marathon Man and Klute by Michael Small, and The Usual Suspects by John Ottman. I could add another five, and another five after that as music is more often than not the way into a scene, a situation, a mood. I write with music, but reread without music: there’s always the danger of a dodgy piece of writing flying in under the radar because the music made it sound better than it was.

Top five hometown spots?

London – actual hometown: the gardens of St. Paul’s Church in Covent Garden; the stacks of the London Library; the main hall of the Natural History Museum; a massive, twisted old oak in my local park; Oddono’s ice-cream parlour in Northcote Road (Always ask for the hazelnut – they won prizes for it).

Seattle – U.S. hometown: the strip of pebble beach before Three Tree Point and opposite Vashon Island; Kobe Terrace park, in the third week of March when the cherry trees are in bloom; Le Pichet, French restaurant near Pike Place Market; the spot at the bow of the Bainbridge Island ferry, watching Winslow getting bigger on the horizon; a table upstairs in the Athenian Inn in Pike Place Market from where I can watch the comings and goings in the harbour.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Finding Nirvana

"Aberdeen is what you would call a shithole," Belgian cartoonist Gerrit De Bremme writes late in his debut comic Kurdt. "The economy is dead and there is not much happening." De Bremme has traveled from Europe to the Pacific Northwest in search of Kurt Cobain's birthplace. He's not a Nirvana superfan, but he's fascinated by the icon that Cobain has become, and he's hoping to find the humanity at the heart of the rock-star narrative that's grown up around the Nirvana story.

Kurdt is an impressionistic travelogue comic — much of it seemingly drawn from photoreference — with De Bremme's thoughts overlaid in a series of captions. It reads like a dreamy, earnest documentary, and part of the thrill for Seattle audiences is seeing De Bremme's interpretation of local landmarks like Gasworks Park, Green Lake and the seediness of Aurora Ave. The book is illustrated in a heavily polarized black-and-white, with panels that resemble overexposed photographs. And De Bremme has doused each page in moody shades of blue, reflecting his own state of mind and his interpretation of the rainy Pacific Northwestern climate.

At times, Kurdt gets a little too earnest, and De Bremme allows himself to collapse into cliche. (The most egregious line: "Now I'm back in the Emerald City, ready to tackle that big grungy elephant in the room.") These lapses in narrative discipline are common enough in books about iconic celebrities — there's not much substance to grab hold of in the entirety of Cobain's 27-year existence, so writers tend to get a little too vague, a little too grandiose, in their interpretations. When De Bremme stares directly at Cobain, he's furthest from understanding him.

But Kurdt isn't really about understanding Cobain any better as a human being. It's about how the places we're from shape us, and how we either grow beyond those formative experiences or we stay rooted in place forever. It's about traveling halfway around the world for basically no good reason and trying to make the most of it. It's a tone poem about De Bremme finding his place in the world, even in a place that's as far from his home as is humanly possible.

Barnes & Noble announced yesterday that they hired a special firm just to handle the sale of the company. This could mean that Barnes & Noble is about to sell, or it could mean that Barnes & Noble really wants people to think it's a valuable company that's about to sell. Is it a bluff, or is it real? We'll find out soon enough, but I'm thinking January of 2019 is going to be a bad month for Barnes & Noble employees.

Last week, the city of San Francisco gave 11 independent bookstores $103,000 in funds.

The city, in partnership with the nonprofit Working Solutions and the Small Business Development Center, awarded 11 bookstores grant money, including five in the Mission: Dog Eared Books, Bolerium Books, Mission: Comics & Art, Adobe Books & Art Cooperative and Alley Cat Books.

The money is part of the Bookstore SF Program, a pet project of the late Mayor Ed Lee, aimed at funding bookstore “revitalizations” that emphasize their roles as social hubs rather than simply places to purchase reading material.

Maybe it's time for Seattle — an international City of Literature, recognized by the United Nations, no less! — to consider doing the same.

Invaded Life Forms: Talking with Calvin Gimpelevich

I once read a very woo book that said our spirits were fifty feet tall and part of the awkwardness of being a baby is that we are crammed into these tiny bodies. Readers can feel the immensity of Calvin Gimpelevich’s spirit unfurl in his writing as he captures the absurdity of being in a body on this planet in a society that continually attempts to restrict our possibilities.

Calvin has been organizing art shows and performances in Seattle with the queer art collective Lion’s Main for years, and his debut collection of stories has been a long time coming. Invasions (Instar Books, October 2018) brings the lens of queer and trans fiction and flips the script on the "real world." The stories in this collection capture the isolation of being in a body in a world where what you appear as determines the limits of who you are. A six-year-old girl wakes up as a middle-aged man; a narrator becomes trapped in the minds of other people; other characters swap bodies only to long for their own somatic memory.

In a time when toxic masculinity is under speculation, and the #MeToo movement is embroiled in who gets to claim it, the gender outlaws in Invasions lead us into the deeper explorations of these power dynamics through a different collateral of social power and powerlessness.

In preparation for his book release at Elliott Bay Book Company on October 28, we spent some time discussing speculative fiction, structure, and the possibility of the body. This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

These stories exist at the intersection of speculative fiction and realism. It’s almost as if you’ve warped which is which. We are invaders in these bodies and trying to sort out how to make the shape connect more and are trapped in how other people see us. Is this accurate in your experience of writing these stories? Can you talk about your process of blending realism and speculative fiction?

I lived for many years with my grandmother, who was schizophrenic (my mother being her legal guardian). I remember so many instances of failed communication in which we were unable to move beyond fundamental disagreement of fact. This failure seeped into my adult life, where — both professionally and personally — I've been around many people whose sense of reality doesn't match mine, and where I've realized that my own reality is not necessarily objectively true. I feel best about an interaction, not when I've managed to convince someone that my perspective is right, but when multiple perspectives are allowed to exist, showing what is unseen in our own. The traditional concerns of literary fiction (which I tend to think of as focusing on internal, as opposed to external, action) are almost always more interesting to me, but I've found it natural to dip into speculative work to explore those concerns.

So is it almost like speculative fiction makes it possible for multiple perspectives to exist. Who are some of the writers who helped form this craft approach for you?

Rushdie talks about magical realism as being as legitimate (or accurate — I don't remember the specific wording) as realism, that there is a tyranny in only one accepted perception of fact. I've gotten a lot out of surrealists and magical realists: Allende, Calvino, Morrison, Kafka, Bolaño. Kundera's Unbearable Lightness of Being is still one of the most beautiful perspectives on multiple realities that I've read.

Something the stories truly captured for me was dysphoria — I don’t think I had seen my own experience of it manipulated so well in literature. Particularly the strangeness of being in these heaps of flesh. In "Transmogrification," a story told in the second person, a six-year-old girl wakes up as a middle-aged man. The stories and the narrations get inside my body and take over. How do you see POV at work in your stories to create this effect?

“Transmogrification” is the first short story I wrote (after an attempted novel in high school). I was eighteen — two years from realizing I was trans. At that point, I was so alienated from (and confused by) my own body, that second person — the disorientation of it — seemed better.

You mentioned, earlier, being trapped in how other people see us. Personally, that was as large a piece of my own dysphoria as the physical reality of my body before hormones.

Your stories often seem to start and end in the middle, which I think is a more accurate experience of storytelling. It's also true in the way we think about transitioning in the body. I think a cis audience might think that there is a narrative: gender discovery, hormones, surgery, FIN but it never or very rarely ties up that way. The narrator in your story "Runaways" wonders what's next when he's finally done saving for surgery. How do you find endings in situations and stories where it is philosophically impossible to locate them?

I got obsessively interested in narrative structure in my early twenties, which led to a lot of research, and a drafting process for my own work involving diagrams, numbers, and graphs. I've calmed down (until I teach or edit for other people, which always turns into a rant about five-act structure and kishotenketsu and other things you probably don't need to know, but that I can't stop fixating on). The boring answer is that the endings come out of my personal understanding of narrative and what the central conflict or story is.

Get nerdy! How are five-act structures and kishotenketsu at work in your thinking with Invasions?

Five-act structure is something I've seen discussed more in film and theater than literature, but I've found it helpful in pacing, character motion, and decisions about events. I use it is to imagine the short story as a single act in a larger five-act piece — like pulling a short film out of a longer movie. Vonnegut talks about something similar, and I think it helps make a short seem like part of a larger dynamic world. The best concise overview that I've found of five-act structure is "The Myth of the 3 Act Structure" by Film Critic Hulk. I make all my students read it.

Kishokentetsu is the Japanese name for an East Asian narrative (and argumentative) structure that places the emphasis on contrast as a means of interest, versus conflict (which is often seen as the only legitimate motion in Western narrative tradition — going back to Greek theater). I've read as much as I could about this structure in an attempt to deconstruct the three- and five-act models I've so thoroughly internalized. I haven't drafted anything purely along the lines of this structure (and doubt I grasp it well enough to succeed), but thinking about it has helped bring certain pieces more depth.

Can you talk about the process of writing "The Sweetness" — about a man whose consciousness can enter into the minds of others through their eyes, and ultimately enters into a cop during a gay bathhouse raid? What is your relationship as a writer to entering into other bodies and experiences? How often do you find softness there?

Empathy! This seems like the whole point of being a writer (or a fiction writer), to step into other people with as much softness and suspended judgment as you can. If I were actually psychic, I wouldn't need to write. But I'm not, so I have to construct other internal realities of my own.

I need to shout out my editor Jeanne who invested a lot in this story, and worked particularly closely with me in the editing process. I drafted "The Sweetness" during a painful breakup, which maybe accounts for the tone. See how melodramatic I am? To express my grief at a relationship ending, I wrote a story where everyone dies. It takes place during "Operation Soap," the actual 1980s Toronto bath raids. Here I was also melodramatic — no one died in any fires in the accounts that I read.

That's so interesting, because the fact of everyone dying really highlighted what's at stake in terms of connection, shame, and human frailty. Especially in the present day, when HIV is still an opportunity for criminalization and of course the criminalization of trans bodies, especially the bodies of trans people of color.

Anything set in the 1980s, especially concerning queer people, makes me think about AIDS. It was hovering in my mind in this story — that the epidemic had such a frighteningly deadly rate, so little understanding, and how hard people were fighting to make their governments care. That Operation Soap–like raids were happening in the midst of this, and that the virus is still used as a means of criminalization, is upsetting. I was just reading Samuel R. Delany's letters from 1986. He talks about AIDS so rarely, but it's always hovering. There is a beautiful letter, toward the end, where he talks about moving out of that fear.

While reading I really felt the isolation of the body and the radical potential of it. In “Eternal Boy” the narrator says “I have emotions I just don’t like to feel them.” Characters continually experience the disconnect between what the body is capable of feeling and what they (their spirit, their psyche, whatever it is that fills these forms) are willing to attempt within those limitations. The stories seem to demand, of course you love, but how much are you willing to feel?

Before writing, I studied psychology, and my patchy professional background centers around social work. What you've just said — the disconnect between what the body is capable of feeling and what they are willing to attempt within those limitations — is one of the best summations of what interested me in that field. Trauma is given, but how does a person respond?

In your stories, they seem to respond through isolation or finding connection. Your stories really capture what's at stake in our loneliness.

Yes — isolation and connection not only in relation to other people, but in themselves.

The conflict in many of these stories is the absence of communal care or the desire for it. What is your relationship to communal care in trans and queer lives and TQ literature? Where do you see possibility, and how can fiction take us there?

It's been interesting to see the response to Invasions, which is overwhelmingly focused on the book as a piece of trans literature. I wrote these stories through my transition, living primarily in queer world. To me, I was writing fiction about people, and the people I was around were queer, so it made sense to explore larger topics through them. I understand that I am writing queer lit, but that's not what I'm thinking about when I work.

I suppose that's what any kind of "fill in the blank" literature is — writing about the worlds that we live in.

Who you are will come through.