Portrait Gallery: Gary Copeland Lilley

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Friday May 26th: Lashley/Lilley

You already know that Robert Lashley is a force of nature. He’s one of the most vibrant readers to come out of the Pacific Northwest. You might not know poet Gary Copeland Lilley, a Cave Canem fellow whose latest book is The Bushman’s Medicine Show. Together, the two of them are a bicoastal poetry assassin squad.

Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St., 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Criminal Fiction: May cowers

Every month, Daneet Steffens uncovers the latest goings on in mystery, suspense, and crime fiction. See previous columns on the Criminal Fiction archive page.

With its friendly staff, shedloads of books, and cool author signings, the Seattle Mystery Bookshop is one of the loveliest jewels in the city’s literary crown. Keep an eye on their event calendar , which showcases the best of mystery writers, local, regional, national and international. On the radar for summer: Cara Black, creator of the astute Parisian PI Aimee Leduc, drops in at noon on Wednesday, June 14, and on July 5, the excellent Jill Dawson, over from England, signs The Crime Writer, her canny fictional melding of Patricia Highsmith, a sleepy Suffolk village, and a spot of murder.

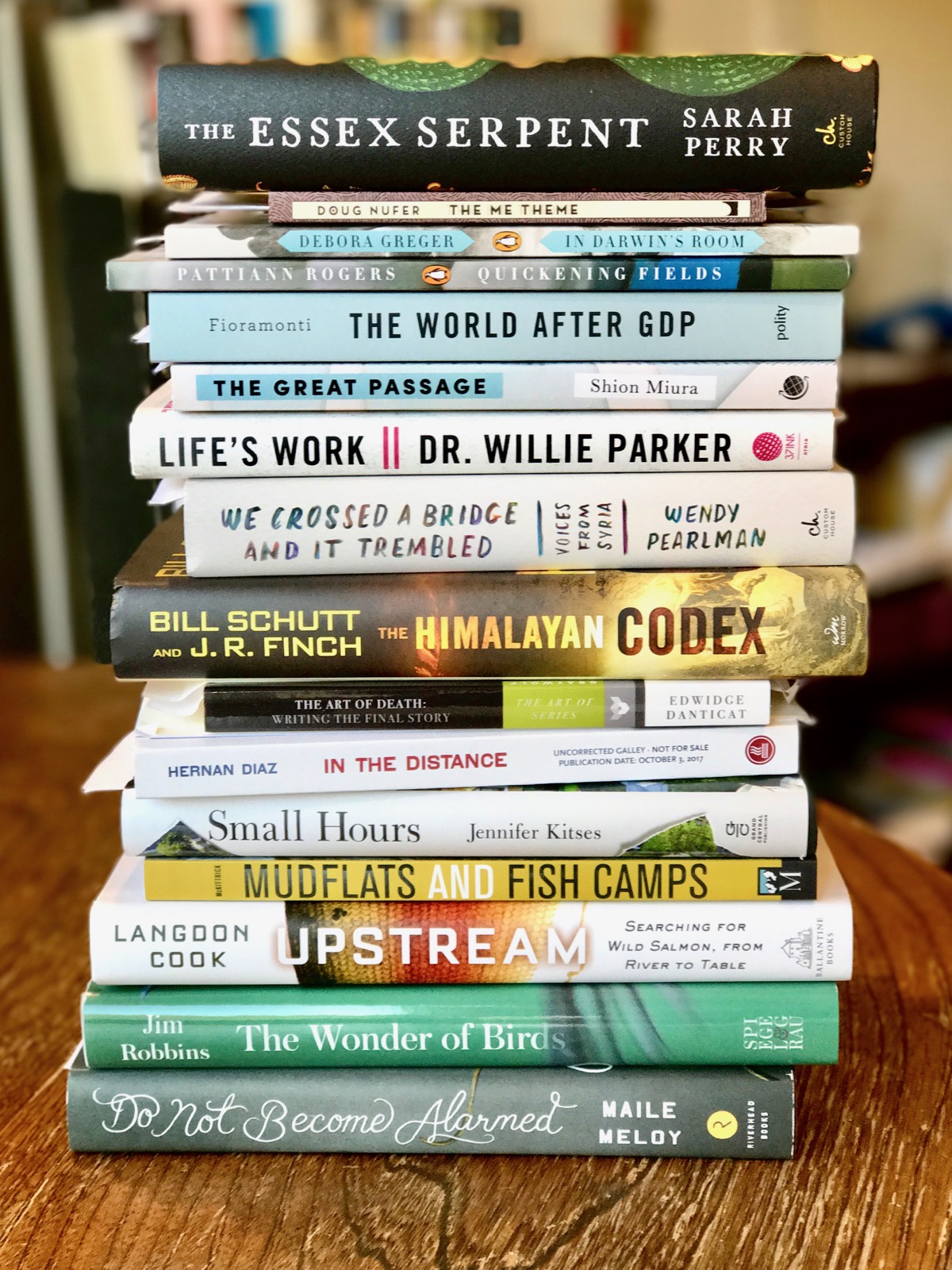

Reading around: new titles on the crime fiction scene

A river with a forebodingly named spot called the Drowning Pool features as a key element in Into the Water (Riverhead). Paula Hawkins’s turbulent follow-up to 2015’s unstoppable Girl on the Train, this psychological thriller is just as rife with twists and turns, but is set compactly in a northern English village, rather than a London suburb. The rural setting lends itself beautifully to the mysteries at hand — a suspiciously high number of people have met their end in the Drowning Pool — and Hawkins has enormous fun with a wide swathe of rotating narrators. She ventures into seriously dark psychological and societal territories here, not the least of which being the hypocrisy and violence that often lies indelibly at the heart of even the smallest of communities.

A cache of bones discovered in a medieval tunnel beneath the city of Norwich piques the interest and curiosity of forensic archaeologist Ruth Galloway in The Chalk Pit by Elly Griffiths (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). But things quickly take a particularly sinister turn as Galloway’s former lover and policeman colleague, DCI Nelson, begins to investigate a series of mysterious disappearances and deaths in the region: from the homeless population to yuppie communities, no one, it seems is safe. Griffiths nimbly weaves a proper police procedural with a gimlet-eyed take on finger-on-the-contemporary-pulse social issues, as well as immersing her characters in ginormous life changes.

The specter of nefariously used social media — Tinder, in this case — raises its ugly head in The Thirst by Jo Nesbo, translated from the Norwegian by Neil Smith (Knopf). But, this being a Nesbo novel featuring the Oslo detective Harry Hole, there’s so much more here than meets the eye, particularly as Nesbo is a master at finely drawn characters: one of the most powerful elements of his thrillers lies in the ways in which his characters interact with and affect each other. Hole — who recently left the police force for the relative safety of a teaching role and is enjoying the more mundane pleasures of life, such as attending Sufjan Stevens and Sleater-Kinney concerts with his stepson — is commandeered back onto an increasingly terrifying case that encompasses vampirism, Shakespeare’s Othello, and crimes both grisly and grim. Excellent, as always.

Nick Mason is still in death-threatening thrall to crime boss Darius Cole in Exit Strategy by Steve Hamilton (Putnam), and it doesn’t get more complicated than tampering with America’s Federal Witness Protection Program — especially when a baddie escapes custody with Mason’s killing on his mind. A fiery, muscular narrative that travels at relentless speed, Exit Strategy is a page-turner, yes, but also a tale of loneliness at its most extreme.

The Quintessential interview: Dennis Lehane

I’ve been a fan of Dennis Lehane since 1994’s A Drink Before the War, which introduced his fiercely compelling and complicated Boston PIs Patrick Kenzie and Angela Gennaro. One of our finest writers, Lehane has added high-profile television credits to his name (The Wire, Boardwalk Empire) and has seen several of his novels transformed into critically acclaimed movies. Since We Fell (Ecco), his new standalone and his first novel told from a woman’s point of view, is vintage Lehane: smart, taut, beautifully written, and not to be missed.

Catch the L.A.-based Lehane at Elliott Bay Book Company on June 5 at 7 p.m.

What or who are your top five writing inspirations?

- Boston

- Bills

- Music (dependent on the book, dependent on the mood

- My daughters (see #2 again)

- My childhood

Top five places to write?

- Writing desk, top floor of my house

- Home office

- Diners and coffee shops (but never a Starbucks)

- Pubs

- Anywhere with an ocean view

Top five favorite authors?

- Richard Price

- Raymond Carver

- Elmore Leonard

- Graham Greene

- William Kennedy

Top five tunes to write to?

This is an ever-changing list. I would conservatively say there are at least 700 songs on my Infinite Writing Playlist and 14,000 in my iTunes library. But for the sake of argument, this would be 5 in constant rotation right now:

- "Birds Trapped in the Airport," Craig Finn

- "We Belong Together," Rickie Lee Jones

- "A Dustland Fairytale," The Killers

- "Slipped," The National

- "Jisas Yu Holem Hand Blong Mi," Hans Zimmer

Top five hometown spots?

- Playa Provisions, Playa del Rey

- Mo’s Place, Playa del Rey

- Scopa, Venice

- Good Stuff, El Segundo

- Bodega, Santa Monica

Thursday Comics Hangover: Rolling the dice for charisma

It's a kind of nerdception: Rise of the Dungeon Master is a biography of Gary Gygax, inventor of Dungeons & Dragons, told in comic book form. Writer David Kushner and artist Koren Shadmi do excellent work transforming what could be an incredibly dry subject — Gygax's slow construction of Dungeons & Dragons from pieces of miniatures-based military reenactment games — into a breezy biographical story. Rise is a book that shouldn't work, for several important reasons.

It's told in second person. While just about any writing instructor would urge a biographer to not write a book with "you" as a subject, second-person works here because it follows the format of a Dungeons & Dragons game. ("Your mother also fills your imagination with adventure," the captions inform Gygax like a Dungeon Master equipping a player for an oncoming battle, "she reads you Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn.")

Shadmi's art is very cartoony. Realism isn't necessary for a biography — Peter Bagge, with his rubber-armed figures, has somehow become one of our best comics biographers — but the mundanity of Gygax's upbringing and the gaudy muscularity of Dungeons & Dragons would seem to call for realism. Instead, Shadmi's likenesses, with their big, rounded Disney faces and their exaggerated poses, somehow add to the familiarity of Gygax's story, making him more relatable.

There's not too much of a narrative arc. The story follows D&D's meteoric rise in popularity and its controversial period in the 1980s when it became associated with Satanism and juvenile delinquency, but generally not too much happens in the story. Gygax is a dedicated process nerd who invents the game, and it quickly becomes an American standard.

Despite these seeming drawbacks, Rise works on multiple levels. Kushner ingeniously compares D&D to an operating system, and that metaphor instantly gives the story of the game a more familiar shape. At this point in the 21st century, we know the story of the successful Silicon Valley startup by heart, and that tech creation narrative lends its own drama to D&D's history, adding a friction that other accounts of Gygax's life don't really enjoy.

One major flaw of Rise comes in a choice with the book's lettering. The second-person narration captions are the same basic shape as the captions that contain Gygax's quotes, often leading to a confusing mishmash of perspectives, switching back and forth from "I" to "you" without much of a visual difference besides some ragged caption borders. A stronger visual cue, such as putting quotes in rounded word balloons rather than square ones, would make for an easier, less-muddled reading experience.

But aside from a few stumbles caused by that muddled narration, Rise is a chatty book that neither wallows nor sidesteps its subject's inherent wonkiness. D&D nerds and novices alike can find new information here. It's a miracle of explanatory storytelling, and it builds to a climax that is artful and genuinely affecting. This biography is more than just a series of things that happened — it's a celebration of a genuinely new invention that changed the course of history.

Not only has William Gibson proven to be the living sci-fi novelist who is best at predicting the future, he is also an absolute joy to follow on Twitter. And when Gibson is not retweeting current events that sound like he invented them 25 years ago, he is complaining that the future is moving too damn fast:

Ridiculous contemporary shit that makes my job harder. Thanks, Singapore https://t.co/OAFfUeLIAk

— William Gibson (@GreatDismal) May 23, 2017

I love it when sci-fi writers gripe about the future arriving faster than they can write.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from May 24th - May 30th

Wednesday May 24th: Displaced: Refugee Voices in Conversation

The Northwest Immigrant and Refugee Health Coalition is assembling a panel of refugees to discuss what it’s like to become a refugee in this country, and what life in America for refugees is like right now. These are conversations that everyone should hear — a reminder that Trump’s policies have real repercussions for real people. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, http://townhallseattle.org. $5. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Thursday May 25th: Broken River Reading

J. Robert Lennon’s newest novel, Broken River, is about a husband and wife who try to find a new start in a house with a history of violence. Lennon is sharing the stage with Seattle author Elissa Washuta in her last local appearance before she takes a position at Ohio State University. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave., 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Friday May 26th: Lashley/Lilley

You already know that Robert Lashley is a force of nature. He’s one of the most vibrant readers to come out of the Pacific Northwest. You might not know poet Gary Copeland Lilley, a Cave Canem fellow whose latest book is The Bushman’s Medicine Show. Together, the two of them are a bicoastal poetry assassin squad. Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St., 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.Saturday May 27th: Ghosts of Seattle Past at Folklife

Hard to believe that Folklife is happening already — possibly because it’s been a rainy dismal hellscape for the last six months. But we finally made it! And why not celebrate the death of dismal winter with a special group reading by contributors to Ghosts of Seattle Past, the book which celebrates lost local landmarks? Seattle Center, http://www.nwfolklife.org/festival-schedule/. Free. All ages. 1:15 p.mSunday May 28th: Girl on the Road Reading

Seattle’s Office of Arts & Culture gives out grants to artists of all kinds. One of those grants went to local cartoonist Noel Franklin, for the completion of her memoir, Girl on the Road. This afternoon, Franklin presents a reading from the book, which is about friendship and loss and grief. She’ll also have printed samples of the book available for the audience. Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, http://vermillionseattle.com. Free. All ages. 5 p.m.Monday May 29th: Lost in Translation

Look, you’ve always wanted to read onstage, but maybe you’ve been afraid of embarrassing yourself at your favorite reading? This is your chance to participate in a once-yearly reading. Sign up 30 minutes before the reading, and participants will be selected at random. If selected, you’ll have five minutes onstage, and if you screw — you won’t — you’ll never see these people again. Go live your dream. Seattle Center, http://www.nwfolklife.org/festival-schedule/. Free. All ages. 3 p.mTuesday May 30th: Loud Mouth Lit

See our Event of the Week column for more details. St. Andrews Bar & Grill, 7406 Aurora Ave N., 523-1193, http://standrewsbarandgrill.com/. Free. All ages. 8 p.m.At The Guardian, Danuta Kean wrote a very good post about people who feel compelled to tag writers on social media with their very negative book reviews:

Others seem genuinely to think they are helping the writer by telling them they hated their latest work. All seem blissfully unaware that as a far as the author is concerned, their feedback is unwanted. Their tweet or post is on a level with a stranger shouting abuse in the street.

Remember: authors are humans, too. Maybe don't make them feel like shit unless it's absolutely necessary? This isn't to say that you should skip writing negative reviews. You just don't need to wrap your negative review up in a bow and then drop it in an author's lap.

Literary Event of the Week: Loud Mouth Lit

Nobody’s ever accused Paul Mullin of being soft. Back when Mullin was a playwright, he wrote stories about genius brains being turned to slurry from aggressive radiation poisoning and monstrous men who recall their own horrific acts even through the blessed fog of amnesia. Mullin wrote long screeds about what was wrong with American theater (spoiler alert: basically, everything), and he wasn’t afraid to make enemies. Then, about four years ago, he retired from theater.

Then Mullin published a memoir titled The Starting Gate. It’s about stepfathers and sons and Mullin’s early teen years working in a bar full of colorful characters, and it’s full of fights and threats of violence, but in that chipper John Wayne kind of way, where every fistfight might end in friendship or, at the very least, a grudging respect. Mullin writes that he’s comfortable in the “beer-dank dark of this shit-kicker bar,” and you get a sense that in fact, he might chafe in an environment that doesn’t have a bit of an edge to it.

Lately, Mullin has been running a reading series called Loud Mouth Lit, and it’s got a couple interesting angles to it. First, as curator, Mullin is pulling from his theatrical past. He asks guests who he thinks will be good (by which I mean dramatic and compelling) readers. Second, he doesn’t cram the bill full of six or seven readers: every Loud Mouth Lit is just Mullin and one other reader.

Third, he’s branching out into a very different venue. Loud Mouth Lit happens at St. Andrews Bar & Grill on Aurora, which is not one of these refurbished amusement-park dive bar simulacrums that you see on Capitol Hill. St. Andrews is a bar from a different time and place. It’s a little less butt rock and a little more classic rock: on the menu you’ll find “Rod Stewart Onion Rings,” which are “served with ‘Rod Sauce,’” which may be the single most unappealing name for a condiment since “gentleman’s relish.”

Bringing a reading series to an Aurora sports bar is a baller move, the kind of thing that makes you wonder if maybe literary events have gotten a little too comfortable in their own enclave. If readings are so great — and I fundamentally believe that they are — why not take them out into places like St. Andrew’s, where they can compete with jukeboxes and soccer matches on the satellite TV and abundant booze for relatively cheap?

On Tuesday, May 30th, Loud Mouth Lit features readings from Mullin and local writer David Schmader. Mullin will be reading a piece about his job at the National Archives and a fistfight in an elevator. Schmader says he’ll be reading “About gay mentors with bad boundaries and my short history of having to punch my way out of dates,” and he credits the piece to “Ed Murray, whose current scandal inspired me to write this all out."

Schmader — who is, full disclosure, my former coworker and a friend — is a very funny writer who has a knack for baring the frilly underpants of our most angst-ridden issues in as entertaining a fashion as humanly possible. He can make you laugh about things that you’re afraid to say out loud. His exuberant ninja-assassin style of comedy should blend well with Mullin’s aggressive punch-throwing technique. One’s a tactical genius, the other kicks down doors. I’d watch the hell out of that buddy-cop show.

Putting on a Shakespeare play? The language should be the boss.

Writing theater criticism always made me slightly uncomfortable; specifically, I hated to write negative reviews. I have no trouble writing negative reviews of books, but there's something about the vulnerability and teamwork of a play — a group of people coming together for little to no money in order to strut across a stage and mimic emotional states — that I hate to criticize.

There's not really a logical framework behind any of this. Writing negative reviews of plays always made me squirm in a way that negative restaurant reviews never did, even though a bad review of a restaurant could actually affect people's livelihoods, while a bad review of a play was often like insulting someone's model train set.

All of this is to say that I recently watched a Very Bad Play in Seattle, and it is more for my own comfort than the theater's that I am not going to name the production. The Very Bad Play was an interpretation of Shakespeare, and it was so Very Bad that I'm still thinking about everything it got wrong.

You could tell in the first five minutes that this show was going to be a Very Bad Play. The Badness was immediate and it was thorough, plaguing every aspect of the production from beginning to end. I could write a laundry list of its flaws, but I'm not out to attack anyone in particular, here. And I think all of my problems stem from one very specific failure of the production. That failure boils down to this: They didn't respect the language.

Shakespeare's language is the source code of everything we say or write even today. It is as close to sacred as this atheist can fathom. So if your production mangles the language by piling overacting on top of it, say, or by screwing up the delivery of it with musical interludes, or by — worst of all — adding to it, you are basically committing a crime against the English language.

You can't outdo Shakespeare. Don't even try. And if your production isn't interested in bringing the language to life — if you're treating the script as an obstacle to overcome, say, rather than something wondrous to extol, you're better off doing something else.

As a writer and a reader, I tend to put too much emphasis on the script in a production, at the expense of the acting and direction and design. But when you do Shakespeare, the script is the thing, and you are working in service of the script. I firmly believe this. And if you don't serve the script, and if I pay to see your play, I will always remember your production as a Very Bad Play.

Book News Roundup: Book bingo, diversity training, a guest for Short Run, and an award for Jess Walter

Does your organization need diversity training? If you're an arts organization in Seattle, the answer is probably yes. This Saturday in the 2100 Building at 1:30 p.m., two local artists with lots of experience in the topic are hosting a "public discussion about the pros and cons of working with professionals, consultants, and hands-on-experts to facilitate an anti-racist work environment." Entry fees range from $5 to $20, though nobody will be turned away for lack of funds. You can confirm for the event on Facebook.

Short Run has announced a new special guest for their November festival: cartoonist Julia Wertz. You should be excited about this news: Wertz is a spectacular comics memoirist (you should read Drinking at the Movies) who is moving into a new phase of her career with illustrations of American city streets, many of which will be collected in a book this fall titled Tenements, Towers & Trash: An Unconventional Illustrated History of New York City. Wertz has gone from the creator and star of an online strip called The Fart Party to a regularly published cartoonist at the New Yorker. The Short Run Festival happens at Seattle Center this year on Saturday, November 4th.

Spokane novelist Jess Walter will be given the Humanities Washington Award this October for his "commitment to nurturing creativity" and his lifelong dedication to the humanities.

It's Summer Book Bingo time again at Seattle Public Library! Here's how it works: download a bingo card from their website or pick one up at your neighborhood library. Then, read books that meet the criteria on the bingo card (categories include "adapted into a movie," "published the year one of your parents was born," and much more). Check those books off on your card. If you fill your card and turn it in, you could win a collection of books from authors who are coming to town for Seattle Arts & Lectures' 2017-2018 season, along with tickets for every one of SAL's upcoming shows.

The Seattle Globalist is looking for a summer intern.

A Story Problem #3

A cart carrying a metric ton of apples leaves the city at four meters per second. Another cart leaves the city carrying a boy, in love with an idea. Consider the swirl of laughter and personal tragedy at 6 meters per second. Say the idea does not love him back. Say he will lose his life in a maze of regrets. What can be said about the dust caked on the wheel spokes and the precarious sway of the chasse crossing over ruts and the staggered pavers knuckled together side by side. At four meters per second is there enough time to sample what is carried? Say the apples find their way into the basket of a family a dozen miles away before the boy gets there. Where did he stop? Did he consider the essence of the problem? If the distance of love is coupled by the weight of an apple cart bound for the markets or bazaars of a city as far away as autumn, then what can be said about the horses who will never taste their burden? Where will his cart pass the adenoidal fruits along the road? Where will he know the plurality of his blood?

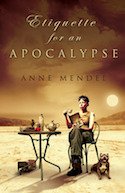

Cocktail hour in Portland, after the fall

Sponsor Anne Mendel delivered us a full chapter from her comically twisted dark novel Etiquette for an Apocalypse. Set in Portland in 2020, Mendel gives us a future when humanity is falling apart. But is that any reason to set aside manners?

Read the first full chapter on our sponsor's page — we think you'll really enjoy it. Visit Portland in the near future, and learn all about survival in a high-rise condo during the apocalypse.

Sponsors like Anne Mendel make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? Get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

A Ugandan filmmaker has discovered a new way to combine storytelling and movies

On Saturday, SIFF presented the West Coast premiere of Bad Black, an action movie from the Ugandan micro-movie studio of Wakaliwood. An American producer named Alan Hofmanis was in attendance to present the film and lead a Skype Q&A with director Nabwana I.G.G.

From a storytelling perspective, Wakaliwood films are unique in all the world. Hofmanis explained the history stretches back some three decades, when VHS tapes of American action films started circulating around the poorest parts of Uganda. There were no subtitles, and many in the slums of Uganda are illiterate, so instead a person would narrate the film for audiences, explaining the dialogue and action as it unfolded on the screen.

The narrators began to get artful with their commentary, making up storylines (Hofmanis said one retelling of Air Force One includes the backstory that the leader of the terrorist organization slept with the president’s wife and gave the First Lady an STD) and adding jokes and color commentary. When Wakaliwood started making movies, the narrators became more like the hype men at a hip-hop show, using hyperbolic color commentary to talk up the action on screen and to emphasize the heroism of the protagonists and the villainy of the antagonists.

Bad Black opens with a character named Swaz (the narrator shouts, “The Ugandan Schwarzenegger! Swaaaaaaaaaz!” much of the time that he’s onscreen) who gets into a gun fight with some troops invading the hospital where his pregnant wife is giving birth. The action unfolds all around the slums of Wakaliga, where Nabwana I.G.G. was born and raised. His friends and neighbors all participate in the film. Nabwana uses practical and (very low-fi) CGI effects to enhance the action.

For American audiences, the most fascinating aspect of Bad Black might be how much American pop culture — particularly 1980s American action films — have permeated the film. You’ll find references to the Karate Kid, Commando, Rambo, Wesley Snipes, The Expendables, and many more films and actors in the 80 or so minutes of Bad Black, most of them inserted by the narrator. And for Seattle audiences, there’s a special treat — Nabwana included a couple of Seattle-centric introductions shot specifically for SIFF.

I’m still wrestling with the questions of colonialism and appropriation in the presentation of Wakaliwood films. A white American producer — albeit one who moved to Uganda to help Nabwana bring his dreams to wider audiences — presenting a Ugandan film for the enjoyment of a mostly white Seattle crowd for the sake of laughs was a bit unsettling.

But is that really any more unsettling than the background child actors in Bad Black wearing our cast-off Spongebob and Rugrats t-shirts? Isn’t the fact that Wakaliwood is finally telling its own story on its own terms important? Isn’t it useful that American audiences are seeing the slums of Wakaliga, with its open sewage and its poverty and its lively day-to-day business? There is no such thing as an unalloyed good or bad here. It’s up to you to run the totals on your own moral balance sheet.

I don’t want to give away any of the best punchlines or story beats of the film. The best part of Bad Black comes in the surprise of it — suffice it to say there are some plot twists straight out of Dickens and some meta-punchlines worthy of Mystery Science Theater 3000. It’s a giddy delight — Nabwana and his friends are high on the very act of filmmaking, and that excitement absolutely transfers to the audience.

But ultimately, for me, the uniqueness of Bad Black all comes back to the narrator. That extra layer of storytelling plays into the wildness of the cinema and makes the whole movie, with all its fake blood and ramped-up conflict, even more enjoyable. It reminds you that the experience of going to a movie is just that — an experience, and one to be enjoyed as thoroughly as possible.

Bad Black plays again tonight at the Egyptian and on Thursday, May 25th, at Majestic Bay.

Processing abuse with art: how Ksenia Anske makes horror and dark fantasy from real horror

I've known Ksenia Anske for almost twenty years. We were both students at Cornish College of the Arts, studying design, at the close of the Twentieth Century. A Russian who came to design school after studying architecture in her home country, her approach to design was always engaged, probing, and driven.

We'd occasionally stay in touch, but I hadn't talked to her in years when I heard she was one of the first round of writers (along with Seattle writer Scott Berkun) to be awarded the Amtrak Residency.

Her absolutely direct, and no-holds-barred, approach to writing, publishing, and getting the word out to her more than forty-six thousand Twitter followers is both intense and, I think, irresistible. As is her brutal honesty about her motivations and the difficult spaces she works within.

The interview has been edited for clarity.

Today you tweeted about how frustrated you were with the scene you were writing. You're very vocal about your writing on Twitter. What does that do for you? Why do you like doing that?

It keeps me accountable. You know, if you're just alone at home, and you say "okay, this didn't work" — then you can say "all right, fine. I'll just forget about it and walk away." But if you actually state it, there's this feeling of guilt if you don't do it — because so many people have seen it. You think "oh my god, tomorrow they'll ask me about it." I mean literally, it's accountability.

Also, these are my readers, and my friends. Which is true: as a writer, my readers are my friends. I don't really go out much, and I don't really socialize. I have all these people in my head, and I'm on my own. I like being alone, I like being in silence. So these are the people who are waiting, and they've been waiting for too long for this particular book, since I won the Amtrak Residency and started writing it on the train. That was last March. It's the first book out of my — what is it? eight or nine, or something, I don't remember the number — that took me over a year to write. And I just can't wait to be done with it, but I cannot ship product that's unfinished, you know? This is my product.

So by tweeting, first, I'm venting — so that somebody will pat me on the shoulder and say "hey, you're doing okay." It helps; it's like "all right, sorry, I just whined for five minutes, I've lost it, I'm good now."

And second, it's accountability to all these people who pre-ordered the book: "hey, look. I'm working on it. I haven't forgotten. I'm not giving up." Every day I get up in the morning, and I get my coffee, and I start fixing it. This scene — today was the fourth day I'm fixing it, the fourth time I'm writing it, because it just wasn't right. So I get frustrated. But after I talk about it, I feel better. It's like you go out and shout in the world, "I'm angry," and then you go, "I got this off my chest, thanks for listening, I'm happy now."

Some writers kind of go away and close the door of their room, and then it's a black box, and you don't hear anything until the book comes out. You're very vocal not only about the process of writing, but also about the stories behind what you write and why you're writing. You go to some pretty dark places, both in your fiction and when talking about it.

Yes. My entire writing career started with me wanting to commit suicide, which is a really dark topic. People usually don't like hearing about it, and people who have gone through it don't know how to talk about it — or sometimes are afraid to talk about it, because it's still not a topic to discuss freely. Also depression; any kind of a mental illness or any kind of disorder that touches or somehow affects your psychology.

Especially if you're an artist. You're supposed to be the starving artist — there's this image we all have about that artist who's a little bit crazy — but it's actually a really, really serious topic, and it's a really big problem. Most of us creators and artists come to creating art from a dark place — when we hit the wall in life and art saves us.

We find a way to take this ugliness and make it into something beautiful. Not everybody can do it, but those of us who can, feel happy. It stops eating you from the inside, and this is why I'm sharing so much because ... let's say I came from a place in my life where I really wanted to die, where you stand there and you hate yourself and your life so much that you want to part with it. And then something happens. In my case, it was my children. I thought about them, and I thought, "this is really selfish, this is actually really terrible," and then it wasn't about me anymore. I couldn't leave them alone, and I decided not to.

And in that moment, something shifted. I stopped being afraid of things that I usually would not talk about. Like you're saying: dark places and dark things. Well — the fear fell off, after I decided to live. It just didn't bother me anymore, all these little problems were non-problems. And sharing this experience was what pulled me out of it.

Also my therapist literally told me to journal. I would go through these horrible panic attacks, and she told me, "You're going to buy a journal; you're going to write yourself out of those." That's how my writing started. That's how my trilogy started. I still have that journal! It has skulls on it, very fitting. It's black and has got really disturbing things inside of it, and I'm going to save it, because that was my road to writing, that was my first step toward it. That's why I don't have any fear about it anymore. It's gone.

I'm imagining you were journaling about things that were happening. How did you go from journaling to processing those things through fiction?

You know, surprisingly, I have been doing that since I was very little. I grew up in a very violent household, and I was abused in a variety of ways. I tried to cope with it as a child by being very silent — that was one of my weapons against adults who hurt me: I would not talk. Sometimes I would not talk for weeks.

I had a crazy imagination, which also is very typical, although I didn't know it at the time. As a child, when the people who hurt you are relatives or people who are supposed to love you and protect you, you can't process it — that somebody like that would hurt you. As a child you can't survive. So what you do is you suppress it, and you replace the image of that person with, often, an animal — something that is dark and scary. Usually it's a dog or a wolf or a bear; some kind of entity, some kind of animal, that in your child's mind you can justify would have hurt you, eaten you, bitten off your leg.

In my family — apart from the darkness and the anger and the hurt and the pain, and everything that was in there for generations that created the environment I grew up in — in addition, the culture in Russia was very well read and very intellectual. My great-grandmother had this huge library of books in her room. I'd been reading since I was very small, since I was four.

That was my solution to all my problems, and that was my helper: it was the books. I couldn't ask the adults about what was happening to me, so I would go and read books ... and I read books that I was not supposed to read, I think, at that age. But also things were happening to me that were not supposed to happen to me at that age. So the books explained it to me. For example, in One Thousand and One Nights, there's one fairytale about a gorilla falling on a woman — basically, a gorilla having sex with the woman — and I remember that it explained everything to me. I thought: "Oh, okay, this is normal. Oh, so it's a gorilla."

When I went to therapy and started remembering what was happening to me, at first, I remembered something black and furry like a gorilla. Then it was a black man; and then it was a man who was painted in black paint; and after that: "It's my father."

It took me so many layers to get to it, because the truth was pretty horrendous. And this is why it's taking me so long to write this book. Because it's a book about a woman remembering her sexual abuse at the hands of her father — which she has blocked — while she is on a train, and every compartment on the train contains a memory that she has to fight to see. So this, what you're asking about — what's funny and also not funny and tragic — is what I've been doing since I was little.

I would create stories in my head to explain what was happening to me based on fiction. I made it into fiction, and that's how I survived it. Everything I'm writing right now is coming from my five-year-old brain, six-year-old brain, seven-year-old brain ... All these stories that I made up in my head to be content with life and to continue functioning as a child, and then later to continue functioning as an adult. And so it's really not fiction for me.

People keep asking me, "How do you get these ideas?" I tell them they're not really ideas, but nightmares. I wish I had less, but there's so many that I just have to get them out of me. Otherwise I cannot be happy and smiling every day; it's too much. It's like living in a world where you have a trapdoor into a dungeon that you have to go in every day, and there's scary shit down there. Like in the movie The Road, have you seen it?

No, I haven't seen it.

Well, you probably read the book.

Yep.

If you watch the movie, there's this scene where they come up and find this house where people hold hostages. In the book, it made my skin crawl — but the film, it's amazing the way they did it. Now when people ask me [how I get my ideas], I tell them "just go watch that scene." That is what I have in my room.

And that is where I have to go every morning. It's horrible, but once I get through it and I come out — and it's 3 p.m. and I'm done writing — I'm this happy cat.

You know, I heard from someone once that horror writers are the happiest and the sweetest people in the world.

It's because they process all their stuff, all their bad feelings and fears.

Yeah! So what I'm doing every day now is really what I've been been doing since I was little. Except now I'm putting it into words.

You mentioned reading, and you're obviously a lifelong reader. You publish the books you're reading on your Instagram feed, and you're a pretty voracious reader, it seems. What have you been reading lately that has struck you or that you like?

I'm trying to read books on business and on writing and how to plot. And at the same time I'm trying to read fiction, novel writers who can teach me how to write novels. And also short stories; every morning before I start writing, I read a short story just to prime myself for a particular style. At the moment it's Petrushevskaya, I'm re-reading her short stories. This one is There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister's Husband, and He Hanged Himself.

What a title.

Yeah, very lovely. She has been not published for a long time, she basically has been banned from publishing her stories in Russia, although there's nothing political in there and nothing really to persecute. But the government didn't want people to know the real lives of real people. The horrendous, dark shit that they have to go through. And she wrote about it — there's no beautifying it, no prettifying it. It's pretty dark and it's very stark and very painful. But there's this humor in it, this survival, and I absolutely love it. Her style is very simple. It's kind of like a fairytale: "there once lived a woman and her neighbor woman had a little baby and she wanted to kill the baby." She gives me inspiration to stop trying to "write," and just tell my story.

Another one I've been reading lately — I met the artist Victoria Lomasko, and I'm reading a book of hers that's journalism with illustrations. She talks about Russian people and their everyday lives. People on the outskirts of society, the sex workers, the kids in juvenile prisons, the LGBT people, and so on. It's very enlightening, because some of these people — even I was not aware of how their lives are, and the conditions they live in.

And let's see ... this book just absolutely changed my plotting. It's called The Story Grid, by Sean Coyne. I recommend it to everyone, and if I had the money, I'd buy it for every writer, because it taught me — based on reading The Silence of the Lambs, which is one of my favorites — how to hack your manuscript, and how to shape it into something that has very distinct parts. There's so many ways of doing it; it's just that his particular formula works for me really, really well.

You have every single one of these books on hand right here with you?

Hold on, I have this one, I'm actually really enjoying this one, it's very beautiful — it's called The Brief History of the Dead by Kevin Brockmeier. It's a sort of apocalyptic novel about the world dying from a virus, but told from the perspective of the dead people, who don't really die until everybody who remembers them dies as well. So there's this in-between place. I'm enjoying it.

Next I'll be reading City Infernal by Edward Lee, which is supposedly this dark horror kind of a paperback book in America, which I haven't really read much. I mean, I love Stephen King, but this one has a bloodier kind of opening. Oh, here it is: "The man walks with difficulty down the street. The street sign reads ISCARIOT AVENUE. He is carrying a severed head on a stick, and the severed head talks. 'Can you spare any change?'"

I mean this is just perfect, this is my kind of stuff! I've seen all kinds of reviews of this, from one star — saying this is just awful, cheap horror — to five stars — saying 'this is great!' So I'm going to read this ... and god, I can talk to you about books for hours. I try to read about one hundred books a year, and this year, because of my editing, I don't think I'll hit the goal, but that's usually my goal.

You give all your books away for free on your website. And then you also sell bound copies. Why did you decide to give everything away for free?

Well, that goes back to the suicide and depression. My book literally saved my life, writing my first trilogy, so I vowed to give it away for free to anyone. Because it does talk about suicide, it talks about teenage suicide, in particular.

When I wrote my second book, Rosehead, people asked, "what are you going to do now?" And I said "What do you want?" And I had so many student readers who said, "I don't have money for books." So I said, "You can have it for free; it will all just even out." There's a donate button, and people occasionally donate; somebody recently donated $100. I was like, "Wow! That just paid for all of these free books that people downloaded."

But I also sell paperbacks, and I sell e-books on all kinds of sites. The idea is: you pay what you want, or you pay if you have money. Even on my website, you can choose to pay what you want. You can pay five dollars, which only covers the cost of the book. Or you can pay nine dollars, and I get four dollars and it pays for my team and for printing costs. Or you pay thirteen dollars, and I can pay my team, it covers my printing costs, and it also gives me another four dollars to invest into my growth as a business.

And you view this as an entrepreneur would, because you ran a company before you were writing?

Yeah, I had a start-up.

I know that's a story unto itself, but how did it change your approach to selling and marketing your books?

The selling idea itself, often people are afraid of it. They think that somehow it's getting into somebody's face and demanding money from them, and they're either shy or they're afraid. They think it's annoying, but that's actually not true. And that's what I learned from my start-up. It's really helping people, holding their hands, and people will be happy to pay you if you just have your shit together.

That's all it is. It's surprisingly easy, because there are so many businesses out there that don't do the smallest things: they don't say thank you, they don't do what they promised they'll do, they don't apologize if they screwed up. If you just behave like a human being, people will love you — they'll shower you with money, they'll come back to you.

Because it's so hard — I mean, life is so chaotic. We're bombarded with all this stuff, and people are constantly coming and going. So we come back to the brands that we trust, the businesses that we trust. We say, "these guys have been making my shoes for this many years, and at least they, when everything comes apart around me, will be there doing the shoes. Or if they are going to go bankrupt, because they always communicated with me honestly, they will tell me 'We're so sorry; we're screwed. But do not fret: we'll try to make your shoes.'"

It's the same with writing books. If you talk to people like a human being, saying "I'm sorry I screwed up" —

Here's an example. Today I was supposed to ship books to somebody who won them in my free giveaway, and another person in Canada. It was 2:15, and the post office closes at 3. I was writing; I usually stop writing at 2, but I looked and saw that was 2:15, and I said, "I'll write another 15 minutes. Half an hour is enough for me to walk or bike to the post office." Next thing I know, my son knocks on the door, says "Mum something something," and I look up and it's 2:45. I go "fuck," I jump up — I'm like, 15 minutes is just not enough, I have to change, pull on my biking shorts — then I realize that the box is too large, so I start running around. Finally I think "I can't do it," so I start composing an email in my head: "Hi, I'm so sorry, I got carried away into writing, I didn't ship the books."

And then my boyfriend shows up at 2:57, and I say "I can't do this," and he's like, "Get in the car, get in the car now. Grab your stuff." I jump in, and we get to the post office one minute late. Usually they close right on time. I run in ...

All of them know me, because I've brought them chocolate before. One lady typed in — it took her 30 minutes to type up all these books that I was sending to the Philippines and Pakistan, Iran, England, and — I can't remember, there's pockets of my readers all over the place — India. And so I said "Wow, you work so hard, I need to bring you chocolate." She kind of laughed it off, but I said "No, I'm dead serious." And next time I came, I brought them a box of chocolates. Now they call me the lady who brings chocolate.

So I ran in, I'm like, "I'm so sorry I'm late," and the boss started grumbling. So I said "Hey, but I brought you chocolate," and everybody was like "Yeah, yeah, this is the girl," and she goes, "Oh, that's fine; you can stay for as long as you want to." It's so cute, and I said "See? I paid for my overtime with chocolate."

But yeah — so I came home and I emailed, so happily, to my customers: "I shipped the books." This is a small business. Customer service is number one. I will go and die and hit my face on the ground, get bloody, but I will get those books to my readers against all odds, because they paid for them. I mean that's a miracle, somebody paid for my words, and they're going to spend their time reading them. That's great; it makes me ecstatic.

How do people mostly find you? Word of mouth?

Yeah. I also now have a big readership that suggests my books to friends; also on social media. For example, on Instagram: I send out these books to book readers, and Instagram has these book review Instagram accounts — most of them are kids, some of them are teenagers, some of them are over twenty. They're younger, and so they have these accounts where they read books and they review them, and somebody would just send me a message saying "I saw your book all over the place, all of my friends have it, can I have it too?" And that's how it goes. Or on Wattpad, one day on Twitter somebody asked me, "Are you going to put your books on Wattpad?" And I said, "What is Wattpad?" So I went and I looked and I thought "This is cool." I posted the book, and just this morning I woke up and I had 150 notifications. Why? I don't know! This is one of those things that I wish I knew ... all of a sudden everybody's reading Rosehead.

Yesterday was quiet. Somebody is always reading my books there, but sometimes it just goes boom. And that's why I'm starting to get my business sense together, because I really need to understand what makes those spikes, how to turn them into sales. I make sales when a new book comes out, because all of a sudden people are interested in the rest of my books — if they like this one, they purchase the rest of them. And then it goes down. So there's always a big spike [when I publish a new book], and I have to keep it going constantly to survive. At this moment I'm not supporting myself financially. It's in bursts. And my boyfriend is like, "I'm an investor, when you make those millions"; and I'm like, "yeah, I got you."

And you keep it kind of in the family. Your daughter does all of your book design, right?

She does. I remember when she was a baby, I taught her how to draw. This is what parents do to children: they're just raising them with this hidden agenda. And she laughs at this. Yeah, she's really good; she graduated from design school in Orange, California, and she does all of my book covers.

The best part about it that is we understand each other. I tell her, "Just do a blah blah blah," and she goes, "okay, I got it." I don't even have to explain — a couple hours later it's done.

We're going to change the Tube cover right now. She was traveling, so it was hard to find an image for her. I don't know if you've seen the discussion, but basically it looks like a nonfiction book, so I'm going to take feedback. This is one other reason that I share everything — I get raw feedback from people, and if eight people out of ten say the same thing, that helps me; it helps me write a better book, it helps me create a better product. So, yes, she does that, but then the rest of my team is all over the place. My editor and my proofreader, you know, formatter, and so on.

Anything that we didn't cover that you wanted to talk about?

Well, I'm excited because Tube is going to be done in about two months. Maybe it will take me a few read-throughs, but this is the final draft. I have decided that I could probably keep perfecting it forever, but I can't do it anymore.

What draft are you on now?

This is draft five. And I've never done this many before. Each draft is a complete rewrite; it's not just revising it, I scrub through from beginning to end. So when that book comes out, it's going to be very important. I'm very proud of it; I worked really hard on it, harder than on any of my other books.

It's my best writing so far, and it's also a really important story — like I said, about a woman remembering her sexual abuse. I tried to dramatize the process of remembering something when it's hidden so well in your child's mind inside of you that you're acting like a private investigator, literally going back into your past and reviewing it. And so it was really challenging, because she jumps from present to past constantly. I hope I did the job right. So I'm really excited about that — and after that I'm going to be writing my first thriller, The Dacha Murders.

Cool. And Tube was the one you wrote on the Amtrak residency?

Yeah, when I started that, it was just a goofy kind of idea. I actually didn't think I'd ever win. I just submitted this little paragraph. They ask "Why do you think you're going to win?" and I said something like "Because I'm going to write a book about trains." And then I won. And somehow, because I said that, when I got on the train, I had to do it, so it became a book about the train. But it changed very much from the original first draft.

All of my drafts are on my website. If people are curious, they can download them and compare. That is another reason why I put it up for free on my site — because when I started writing, I wished there was a resource like that where I could go and I could compare something — let's say The Da Vinci Code or one of Stephen King's books — if I could see the very first rough draft and compare it to the final one, that would really help me as a writer. But I could hardly find that information anywhere.

That's an approach to writing — sharing that stuff — that most writers would find horrifying.

Yeah ... and actually, there's another book I'm reading, by Kit Reed called Revision, if anybody is interested — in the back she has examples, because the book is about revision, they're manuscripts of the first draft and the final draft. But it's still not enough. So that's why I'm doing it — to give back to the community and also learn. People constantly send me feedback, so I get better.

Anything else you wanted to add?

Just send me coffee, coffee beans, my PO box address is on my website. Coffee beans will keep me going. If you want more books, send me more coffee.

Do you eat coffee beans while you write?

Yeah. Actually, I need an IV for that.

The Sunday Post for May 21, 2017

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles good for slow consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

The Public Square Belongs to 4Chan

Halfway down, Joseph Bernstein’s article on “He will not divide us,” a public art piece fronted by Shia LaBeouf, goes batshit crazy. Launched on January 20 at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York, the installation was simple and in theory (although: really?) nonpartisan: a sidewalk-facing camera and a line of text for passersby to read aloud. Within a week it was a mosh pit of alt-right trolling, trash, and violence. Then the real fight started: between the artists, the museum, and the community.

By the third and fourth days of the installation, as young men in MAGA hats started showing up to the museum in larger numbers, "He Will Not Divide Us" began to resemble nothing so much as a social network made flesh. There were civil discussions. There were shouting matches. There were visitors squawking about Trump, about “the Jewish word for division, Soros,” about the revolution not being televised, about their mixtapes, about how Bitcoin would save the world, about WeSearchr, about yo, follow my Instagram. There were doxxes. There were well-intentioned founders with institutional backing and idealistic words about free expression; there were early celebrity adopters; there was an initial period of great hope; there was a worsening signal-to-noise ratio; and there were trolls and racists determined to test the boundaries of the new space with provocations and hate speech.

And then, there was chaos.

Gerhard Steidl Is Making Books an Art Form

Rebecca Mead profiles Gerhard Steidl, considered the best printer of photography books in the world — a craftsman so confident he was disappointed by the Gutenberg Bible. Fascinating look at the practicalities of printing (the fine details of ink, paper, and press) and the philosophy of books as beautiful and meaningful objects. As well as the book as more than an object:

Steidl’s family was poor, and his parents had received no formal education. There were few books at home, and it was momentous for Steidl when he received one — Hans Christian Andersen’s “Thumbelina” — as a Christmas gift. Steidl begged his sister to read it aloud to him immediately, and afterward he told his father how much he had loved it. Steidl’s father, angered that the children had finished the book so quickly, struck the sister. Years later, Steidl’s father explained that he had believed the book, having been read through, was now useless; before buying the gift, he’d never been in a bookstore.

See also Craig Mod this week on the maturing debate about print vs. digital reading: “Containers matter.”

Mysterious Island Experiment Could Help Us Colonize Other Planets

In 1843, a jealous James Hooker started a twenty-year evolutionary hack, shipping the first of hundreds of trees to barren, equatorial Ascension Island. Today the island’s “Green Mountain” is lush and abundant — and a new ecosystem is pushing out the old. This is what terraforming a new world might look like: the transformation of a Mars-like wasteland; a slow, painful struggle between native and alien species; and constant vigilance to prevent an epic system crash.

I visit Ascension’s famous Dew Pond. By the 1880s, Hooker’s “mist-catching trees” had formed a small pond at the mountain’s summit, the island’s first freshwater water body. Today, bamboo trunks form a 40-foot tall wall around the pond, knocking together harmoniously in the breeze.

A life-sized, plastic crocodile waits half-submerged in the pond with teeth showing. The faux reptile appeared there in the 1990s as a gag. It quickly developed its own mythology among the military residents. Should they remove the item? Or leave it? No one can agree what to do with it now. The same can be said about the artificial ecosystem all around.

Seattle Writing Prompts: Seattle's Privately Owned Public Spaces

Seattle Writing Prompts are intended to spark ideas for your writing, based on locations and stories of Seattle. Write something inspired by a prompt? Send it to us! We're looking to publish writing sparked by prompts.

Also, how are we doing? Are writing prompts useful to you? Could we be doing better? Reach out if you have ideas or feedback. We'd love to hear.

Look at the little plaque in that picture. It's just a little corner that edges one of the tiles on the 4th Avenue open space in front of Safeco Plaza (the building also known as "the Box the Space Needle Came In"). It's a demarcation, of course, of when you are leaving officially public land and crossing some imaginary, but well-documented, veil onto private land. But did you know that this plaza, and many others like it, are actually official public spaces?

They are Seattle's POPS, or Privately Owned Public Spaces. There are many of them — some, modest and available from the ground floor; others, more grand and on private floors in buildings that you can access any time the building is open. The thing is, unless you knew you were welcome, you might think twice about just hanging out in front of a big building. But welcome you are.

The city has made this PDF list available — maybe someone should visit each one and then document the visits. The guide could be clearer, though. One of the greatest POPS in the city is in the Fourth & Madison Building. Enter the building through the grand revolving doors on 4th. Walk to the left, down the lobby, and find the back elevators. Take them to the seventh floor, where you will find a park in the sky: a lovely public space with a lawn, and tables, with views and a chance to get away from the bustle of the city while still being in it.

Of the many, many, many political tensions in our world, one that is more subtle (e.g., there's nobody on cable news screaming about it right now) is this idea that the world belongs to the owners, as opposed to the idea that the world belongs to the commons. You see this in desires to sell off our public lands, but you also see it in your very city, where the needs and desires of property owners often bump up against the needs and desires of the citizens. Some feel that the property owners should have the upper hand here, but when you choose to buy property in a city, you are entering a contract with the commons of that city. Yes, you have rights assigned to you by law and by ownership, but you also undertake responsibility to the city you've pledged your money and taxes to. You enter a contract, and the benefit is that you get to live where many others desire to live as well.

This tension played out, through pieces of art, twice at Safeco Plaza.

One: Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae, by Henry Moore, was purchased and installed by Seafirst National Bank, who owned the building, in 1971. After Bank of America bought the building in 1982, they sold the sculpture (and the building) to investors in Japan. After a public outcry, Bank of America purchased back the sculpture and donated it to the Seattle Art Museum, who still officially own it.

Two: A massive — eighteen by thirty-six foot — painting by Sam Francis used to hang in the marble lobby of the Seafirst building (aside: walk through the building. Take the escalators down to 3rd Avenue. It's a marvelously considered space: austere, beautiful. Designed by NBBJ with a corporate mid-century Asian inspiration) on the large elevator bank wall that stands behind the guard station. The painting was an abstract, facing 4th Avenue. Rumor has it, when Rem Koolhaas visited the site of the Central Library, he looked across into the atrium of the building and saw the crossing patterns on the large canvas. It was his inspiration, if you believe the story, for the diamond cross-hatching that dominates the library's facade. That painting was moved when Bank of America decided to open a museum of its art in South Carolina. There, apparently, it still sits, out of context, inspiring no architecture.

Hmmm. Maybe we've only learned that Bank of America are jerks who don't care about keeping art in Seattle. Let's make up some different stories, shall we?

Today's prompts

There were the cops, lined up, impact plastic covering their faces, armor covering their bodies, standing a line along where the private land started. There were the protesters, walking by, looking at the cops. Wondering why some of them were holding batons. Then there was the troublemaker. Black jeans, black sweatshirt, black balaclava. Then there was a brick flying, and the lines moved towards each other.

Why had she decided to walk down the stairs? She thought it would give her some exercise, didn't think how much 29 floors down would make her knees feel wobbly. She made it out to the street, out to the edge of the public square, before they gave way. Before she skinned her knee going down. Before she looked up to see a hand held out to help her up.

Because she died inside, the ghost rules said she could not cross the boundary set forth by the seers who drew the building lay lines. She sometimes haunted those on the elevator, and more than one janitor or night security guard quit before they were employed for a single week. But those minor amusements were erased when the little dog died in traffic in front of the building. Its ghost looked at her now, across that line that divided them, the line that neither could cross. It whimpered as she tried to reach it, determined to find a way.

The drunk men were arguing. "That's it!" one yelled. "Here's the line," he pointed to the metal that demarcated the plaza. "This is it! You cross this line, and it's coming to blows." The other man edged right up, toes against the mark. "This line?" he said. "You mean, if I cross this line?" He picked up his foot, and threatened to move it forward.

The detective pulled his collar up against the wind and rain. 4th Avenue was deserted, except the occasional taxi driving by, splashing water. He flicked his cigarette into the gutter, and waited for that big bad businessman to exit the building. Soon as he crossed the line onto city property, the cuffs were coming out. Inside, commotion. He saw the mark. He raised his hand to his partner on the other side of the building. Time to bust some criminals.

The Help Desk: The online retailer that shall not be named

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

I work at a large independent bookstore. I love my job, but my manager is getting on my nerves — specifically, his tendency to smack-talk Amazon to customers. He’s always launching into lectures about why shopping at Amazon is a bad idea, how they don’t support the community, and stuff like that.

I agree with him! Amazon is bad. But he brings up Amazon a lot. Like, a lot. I know he thinks he’s educating customers, but he sounds like a scold, and kind of a bore.

I’m pretty new at bookselling, but it seems to me that people aren’t going to shop at indies out of guilt. They’re going to do it because they like indies better. And if we lecture them all the time about the “Evil Empire” or whatever, that’s just going to scare them away.

But I’m not really comfortable with lecturing my manager about lecturing customers. Can you think of a way to help me realize that he’s being counterproductive?

Lily, Alki

Dear Lily,

You're right – people don't shop at indie bookstores for bitter lectures from staff on what their competitors are doing. You know this, your customers know this, your boss apparently does not.

But I empathize with your boss's Ahab-esque obsession. One of my favorite northwest pastimes used to be lecturing conservative hunters about how safe access to abortion is a fundamental human right. I firmly believed that everyone would agree with me if they just first gave me three hours of their undivided attention, preferably somewhere festively claustrophobic, like the bathroom hallway at a house party.

It's easy to fall into the habit of such selfish soapbox lectures. Everyone loves agreeing with themselves and in these instances your audience is held resentfully captive because they want to buy a book from you or still hold out a vague hope that eventually you'll grow tired of talking and fuck them, and then spend endless mornings making them elk-steak breakfasts until the race wars begin, at which point they might have to hunt you for sport because your name sounds suspiciously ethnic.

I was lecturing one such hunter about abortion and he interrupted me with, "You want to kill babies, get out there and sterilize all those wild horses ruining our public lands. That's the kind of killing I can get behind." And I thought to myself, "This man is an unfuckable genius."

What do northwest rural conservatives dislike more than abortion? Wild horses and wolves. Which is why, just this week I trademarked the names "PlannedParenthoof" and "PlannedParentwoof" and began the process of marketing myself as the northwest's first wild horse and wolf abortionist.

But back to your issue: obviously, your situation is complicated by the power dynamic between yourself and your manager. If your manager is a mostly reasonable person, try approaching him the next time you hear him mention Amazon to a customer and either start screaming something simple like, "ABORT! ABORT! ABORT!" or "I think we'd make more headway with our customers if we thanked them and praised them for shopping with us and left our competitors out of the conversation." If you're uncomfortable with this upfront tactic, you can talk to your manager's boss or write an letter from a "customer" that delicately highlights your manager's Amazon obsession.

To be clear: your boss is not likely to get over his obsession. The key is to find a way to redirect his dour lectures into positive, productive interactions with customers, much like PlannedParenthoof/woof will undoubtedly do for anti-abortionists living in rural communities.

Kisses,

Cienna

Ethel & Ernest is the opposite of your typical comic book film

Last night I decided to go to the movies for the simple reason that after a week of relentless breaking news stories about Donald Trump, two hours in a dark room with my phone turned off sounded like some kind of paradise. I decided to go to an opening night screening of Alien: Covenant. It was a pretty film, and Michael Fassbender turns in an excellent performance, but the movie was ultimately pretty bad — it was a horror movie that forgot to be scary, a philosophical movie that wasn't very smart to begin with, a space exploration movie with no joy to it.

I can absolutely recommend shutting your phone off for two hours, but I cannot recommend doing so for Alien: Covenant.

Luckily for us, SIFF starts tonight, offering plenty of opportunities to get away from the world and into hushed theaters. Today at 1:30 p.m. and Sunday at noon, the animated film Ethel & Ernest is playing at SIFF, and it just might be the perfect anecdote for a loud and dumb world.

Based on a comic book biography by Raymond Briggs (the British cartoonist behind The Snowman, who I wrote about last month), Ethel & Ernest is the story of Briggs's parents, from their first meeting to their deaths. Like the comic, the story is episodic, spanning decades encompassing World War II, the Korean War, and the moon launch. Through it all, Ethel and Ernest live their quiet middle-class lives, raising their son and worrying about society going all to hell because of the kids these days and marveling at technological progress like televisions and freeways.

The film begins with Briggs himself explaining why he wanted to tell the story of his parents, and then it cuts to an animated style that hews closely to Briggs's own illustration. Most notably, Ethel & Ernest features gorgeous backgrounds — what appears to be watercolor portraits of British urban life, with red brick rowhouses and beautiful emerald countrysides. Occasionally, the figure animation looks a tad awkward — sometimes, a movement will stutter, or a character will float in space in an unmoored fashion — but the excellent voice acting more than makes up for those flaws.

It should be clear that Ethel & Ernest is not a film for everyone. Just because it's an animated film does not mean it's for children — the film gets fairly dark — and just because it's a story of a long and relatively happy marriage doesn't mean it's a romantic comedy. Instead, it's a loving and honest portrait of a pair of decent people. Ethel and Ernest may have their prejudices and their failures to empathize with others outside their economic class, but they're always trying their best.

In a summer full of garish sequels that nobody asked for and comic book adaptations that are all starting to feel the same, Ethel & Ernest is a quiet, gently funny labor of love. It's just the thing to take your mind off whatever clownish news is blowing up your phone.

Portrait Gallery: Nisi Shawl

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday May 18th: Everfair Exhibit Opening

Sci-fi novelist Nisi Shawl’s Everfair was one of the best books to be published by a Seattle author last year. Tonight, it inspires a whole new generation of Seattle art. Push/Pull gallery presents new work by Seattle artists inspired by Shawl’s steampunk alternate history of the Congo. Shawl will be in attendance.

Push/Pull, 5484 Shilshole Ave NW, 789-1710, http://pushpullseattle.weebly.com/. Free. All ages. 6 p.m.

Book News Roundup: Nominate your favorite Seattle writer for the Mayor's Arts Awards

There's still time to nominate a Seattle writer you love for the Mayor's Arts Awards! You have until May 25th to "recognize the accomplishments of artists, arts and cultural organizations and community members committed to enriching their communities through the arts." All you have to do is head over here and fill out the form.

And if you'd like to be Washington State Poet Laureate, you can find more information about that in this PDF. The position pays $10,000 per year, with up to $3,500 in expenses paid for travel and materials.

The Spokesman-Review reported on Sherman Alexie's commencement speech at Gonzaga University:

“So ask yourself, graduates, and families and friends: Do you want to be the person suspicious of strangers? Do you want to be the person who turns away strangers from your front door?”

I've talked about how podcasts were my gateway to audio books. I suspect I'm not alone, and publishers are finally getting wise to that.

Scarecrow Video published a wonderful comic by Seattle cartoonist Ben Horak about video stores and horror movies and fear.

Here's an awful headline out of Washington DC that seems entirely believable: "House Votes to Limit Powers of First Black Librarian of Congress."

Fantagraphics cartoonist Eleanor Davis was arrested for protesting the Trump Administration's immigration policy, Bleeding Cool reports.

Many of the blogs who migrated to blogging platform Medium last year are now leaving Medium again.