Archives of The Sunday Post

The Sunday Post for July 22, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Five women accuse Seattle’s David Meinert of sexual misconduct, including rape

Sydney Brownstone reports on accusations of sexual misconduct against well-known Seattle figure Dave Meinert for incidents ranging over 15 years. This isn’t just a story about allegations of shitty, coercive behavior and worse; it’s also a well-crafted narrative about gaslighting and power — how Meinert’s public persona, progressive and vocal on women’s issues, may have protected him by increasing the inequity of credibility that already favors affluent, high-status men.

Here’s the thing: invading another person’s body has never been okay — as a society, we’ve never said that. What we’ve said (and still do) is that some people have less personhood than others, so invading their bodies is less bad. And if you chose to take advantage of that? Your mistake wasn’t failing to understand the harm you were doing. Your mistake was failing to treat another person like a person. Your mistake was failing to care.

The nuanced, careful reporting in this article is the best kind of counternarrative. Men like Meinert still may not care, but they can be held accountable. Kudos to Brownstone for helping us get there.

The woman decided to file a police report in part because of a Facebook post that Meinert had written on the #MeToo movement — the same post that rankled the business woman who accused him of rape.

Meinert’s post said he wanted his friends to know their sexual assault stories were being heard, and that he was “making a commitment to be more aware and never become complacent or apathetic to this issue.” The post was liked by nearly 200 people.

Meinert’s college friend was amazed by what she believed to be the post’s total lack of self-awareness. In that moment, she wondered if there were others like her.

On Becoming a Person of Color

Rachel Heng is in Seattle this week, touring for her debut novel, Suicide Club. Here’s some pre-reading for those who can attend, and a consolation prize for those who can’t: her essay about becoming other, as a girl growing into a woman, and as a transplant from Singapore to the United States, and the complexity of being seen through multiple lenses, including your own.

When I am called a person of color in America, what do people see? Do they see the invisible privilege of being foreign-born, of having come from a country that afforded me the upward mobility my life benefits from? Do they see that while the color of my skin today renders me a minority in America, I spent most of my early life an oblivious, privileged ethnic majority? Racial privilege in Singapore, like anywhere else, is complex and multi-faceted. The Chinese enjoy certain advantages for being the majority, but this can be further broken down into dialect group, fluency in English and class, with English-speaking Peranakans historically being at the top of the pecking order. While not raised within this specific sub-segment of privilege, through education, I now undoubtedly belong to it when I am in Singapore.

But I do not live in Singapore. I live in America, where on more than one occasion, I have been told to go home. Even as the familiar rage quickens my pulse and makes my hands turn cold, a part of me feels guilty. I think to myself: you, you with all your invisible privileges, who are you to be angry?

Lane Davis's Civil War

Lane Davis lived on Samish Island in his parents’ home, unemployed and by his own assessment without many prospects. But much of his life was lived online, “shit-talking on the internet,” researching, and writing for 4chan-ish sites like The Ralph Retort. Then his anger crossed the thin line between virtual and physical realities, and an altercation with his father ended in murder. A tragic story, reported by Joseph Bernstein, about how hard it is to tease apart the merely awful from the dangerously unstable in the perpetual adolescence of the internet’s alt-right communities.

Writing under the name “Seattle4Truth,” Lane was an indefatigable culture warrior and a wildly inventive conspiracist. He left a footprint online as wide and weird as his imprint on the physical world was small and sad: hundreds of YouTube videos, thousands of tweets, hundreds of blog posts, hundreds of Reddit comments, and most of all years of chats — Slack messages and Google Hangouts — with his fellow travelers.

But none of those people, the ones who called him Seattle, the ones who called him a friend, had met Lane in person. None of them knew, nor would most of them know for months, what he had done to his father. And none of them had any idea what this man they spent all day online with was capable of.

Including me.

The Sunday Post for July 15, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Peterson's Complaint

“Believe me, you are not too dumb to understand this,” says Laurie Penny, right before slicing Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life and Peterson himself into a paper blizzard of puffery, self-pity, and pretension. It’s a tour de force takedown, every breathlessly brilliant insult backed with rigorous logic, a glorious read for the language alone — and also a determined tug on a needle that’s been moving, a bit, and that a lot of angry people would like to re-set to the status quo.

Angry white male entitlement is the elevator music of our age. Speaking personally, as a feminist-identified person on the internet, my Twitter mentions are full of practically nothing else. I've spent far too much of my one life trying to listen and understand and offer suggestions in good faith, before concluding that it's not actually my job to manage the hurt feelings of men who are prepared to mortgage the entire future of the species to buy back their misplaced pride. It never was. That's not what feminism is about.

Barack Obama's Summer Reading

Barack Obama recommends a short list of books by African authors as he gears up for a trip to sub-Saharan Africa to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s birth. The internet has been very gracious in not snarking about our current president’s reading habits while discussing this list, so I’ll try to do the same. (But seriously. A reading list personally curated by the last leader we had who read at all? Yes, please.)

I've often drawn inspiration from Africa's extraordinary literary tradition. As I prepare for this trip, I wanted to share a list of books that I'd recommend for summer reading, including some from a number of Africa's best writers and thinkers — each of whom illuminate our world in powerful and unique ways.

Hannibal Lecter, My Therapist

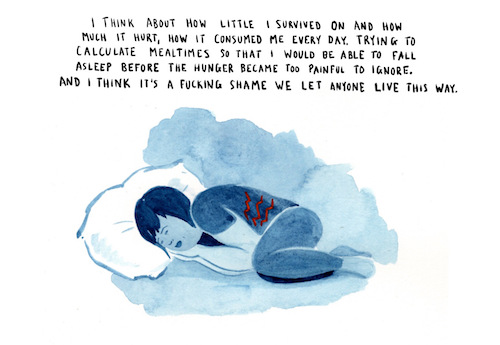

Here are two essays that use small, harmless things as a device to explore the deeply personal. First Emily Alford, who transforms a childhood viewing of The Silence of the Lambs into a grown-up meditation on poverty, neglect, and loss.

There are all sorts of reasons to go hungry: because the only food in the refrigerator is a pot of something crusted black at the edges and baked grey and brown in the center, meant to last all week, globbed on top of hardened white rice and reheated to hot, runny goo in a microwave where roaches dart across the gummy insides, legs sticking to squirts of months' worth of runny dinners. To see how long it takes for someone to notice the untouched plastic baggies full of slimy lunch meat that accumulate in a lunch box, warm to the touch by the time they return home uneaten. To become so thin the wind might catch flaps in a too-large tee shirt and send a body someplace else, like a balloon loosed from a bunch. When I was a baby, the doctor measured the length of my spine and promised my mother I'd be tall, she likes to tell me. Instead, I stopped growing right smack at average, never claiming the length of bone that serves as a reward for being one generation away from poor white trash.

"Was your daddy a coal miner? Did he stink of the lamp?" Dr. Lecter asks Clarice Starling.

Sweetness Mattered

Then Aaron Hamburger, for whom a pack of Smarties helps clear the way to reclaiming himself after a brutal rape. Both of these are difficult, excellent, and best read in private, when you can give them plenty of space and time.

My parents were midwestern-friendly, polite, though they became increasingly silent, even stoic, as I recounted my story. I imagined that no one in the room had ever encountered a shameful and bizarre story like mine, or someone foolish or weak enough to allow such a thing to happen to him. This was the kind of crime that happened to women. But then, after what had happened, maybe I wasn't really a man.

Don't imagine you're smarter

Neal Ascherson on the experience of reading a more traditional kind of permanent record — the files kept by the secret police to track suspected spies. Thought-provoking in this era where digital surveillance, both commercial and political, is an unavoidable fact of life.

The crowning mercy of human relations is that we don’t know what other people are really thinking about us. They — those others — decide what redacted selection we are offered. But to read one’s police file is — suddenly — to have the curtain pulled open. The self you think you know becomes a mask, concealing a devious somebody else whose relationships are mere espionage fakes.

The Sunday Post for July 8, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Survival of the Richest

It’s time for a tech revolution. No, not that revolution — the other one, where we re-write our future without an apocalypse. Here’s media thinker/writer Douglas Rushkoff on the folks who can afford, literally, to be fatalist about where this all is heading. Are we going to sit back and let them build a world only they can survive? Well, are we?

When the hedge funders asked me the best way to maintain authority over their security forces after “the event,” I suggested that their best bet would be to treat those people really well, right now. They should be engaging with their security staffs as if they were members of their own family. And the more they can expand this ethos of inclusivity to the rest of their business practices, supply chain management, sustainability efforts, and wealth distribution, the less chance there will be of an “event” in the first place. All this technological wizardry could be applied toward less romantic but entirely more collective interests right now.

They were amused by my optimism, but they didn’t really buy it. They were not interested in how to avoid a calamity; they’re convinced we are too far gone. For all their wealth and power, they don’t believe they can affect the future. They are simply accepting the darkest of all scenarios and then bringing whatever money and technology they can employ to insulate themselves — especially if they can’t get a seat on the rocket to Mars.

Disposable America

Something’s changed lately in the land of iced coffee: the tide of public opinion has turned against the humble and, yes, environmentally harmful drinking straw. Alexis Madrigal traces the utensil’s history (which is sort of like the story of the three little pigs, if their houses had been made of straw, paper, and plastic) and, fascinatingly, its entanglement with the evolution of capitalism in the United States.

Global competition and offshoring enabled by containerized trade was responsible for some of the trouble American manufacturing encountered in the 1970s and 1980s. But the wholesale restructuring of the economy by private-equity firms to narrow the beneficiaries of business operations contributed mightily to the resentments still resounding through the country today. The straw, like everything else, was swept along for the ride.

Expecto patriotism: the magical yet dark world of Russian Harry Potter rip-offs

Apparently, one of the seven basic plots on which all stories are built is Harry Potter. A thriving sub-genre of Russian fiction is looking to capitalize on the incredibly successful series — but with a few tweaks.

In the Porry Hatter series Harley, a rip-off Hagrid, tells Porry, a rip-off Harry, about the house elves, a magical species recently freed from slavery, led by a character known as Martin Luther King Jr. And, controversially, how the elves, after becoming free citizens, became lazy, living solely off crime. This xenophobic attitude might not be exclusively Russian but is still very widespread here. “Ideas of getting a job and becoming a part of our society turned out to be alien to the newly freed house elves, and they, not knowing what to do with all their free time, started to steal, beg, listen to rap music, and — what would you think? — fight with each other,” Harley explains.

The Eugenicist Doctor and the Vast Fortune Behind Trump’s Immigration Regime

A classic “how the money moves” piece by Brendan O’Connor, showing how powerful a single person’s racism and hate can be — if the person has enough money. In this case the person is John Tanton, an ophthalmologist and eugenicist who used someone else’s fortune so effectively to advance the anti-immigration cause that he might be considered the father of our current ICE. Immensely frustrating to see yet another example of just how much money does, and how the very rich can protect their privilege today while shaping a future where their power will continue to consolidate and grow.

Um. Well, we went a little grim there at the end, but it’s a good read regardless.

While the Center for Immigration Studies bills itself as an independent, non-partisan research organization, it is in fact a key node in a small network of think tanks and nonprofits, founded and directed by a man whose private correspondence contains praise for anti-Semites, fascists, and race scientists of various ideological backgrounds, many of whom would go on to figure prominently in today’s so-called alt-right and financed largely by one of the oldest and wealthiest families in America.

Falling Men

No matter how indifferent you are to the World Cup, this essay by Alejandro Chacoff on the art of the fake fall will charm your shin pads off. Honestly, I had to Google just now to see whether the tournament was over so I wouldn’t embarrass myself (more), and I still followed this to the last delightful line. Like the role of the hockey enforcer, taking a dive in soccer/football (your pick) is one of those sociological side-turns that only sports can offer with a straight face. Read on!

Most of my American friends don’t understand why certain players fall at the slightest touch. The dive is something beyond their grasp. It involves two grave infringements of American morality in sports: a willingness to cheat, and the demonstration — perhaps the celebration — of physical weakness and self-pity. (The flop, basketball’s closest equivalent, is less dramatic and tends to be associated with foreign players.) To be strong and athletic, full of skill, and then to break down once you reach the penalty area seems absurd. In many ways it is.

The Sunday Post for July 1, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

A Cultural Vacuum in Trump’s White House

What I love about this bit by Dave Eggers is that it’s not just a potshot at the cultural ignorance of president who, god knows, deserves any potshots that land. Nope: It’s a thoughtful piece that deftly connects Donald Trump’s rejection of the arts to the authoritarian underpinnings of his philosophy. As Eggers notes, no president on either side of the aisle has carried this level of hostility toward intellectual and creative pursuits. This isn’t about political party, it’s about the icy dead space in the soul of an obscenely, mistakenly powerful man.

The White House is now virtually free of music. Never have we had a president not just indifferent to the arts, but actively oppositional to artists. Mr. Trump disparaged the play “Hamilton” and a few weeks later attacked Meryl Streep. He has said he does not have time to read books (“I read passages, I read areas, I read chapters”). Outside of recommending books by his acolytes, Mr. Trump has tweeted about only one work of literature since the beginning of his presidency: Michael Wolff’s “Fire and Fury.” It was not an endorsement.

In praise of (occasional) bad manners

Freya Johnston reviews, with great historical intelligence, Keith Thomas’s recently published The Pursuit of Civility. As well as an interesting tour of how politeness has evolved through centuries, her essay is a reflection on how manners are a language: an exchange, defined for a particular purpose by particular people, usually those with privilege to burn, and usually received by those without.

Courtesy, and the insistence on it, can be used to subjugate. By the same token, refusing a seat at one’s restaurant to someone whose political views are not just disagreeable but reprehensible may be rude — but the breach may also be a statement of humanity.

One theory of civility will tell you that it is all about acknowledging the separate existence, property, privacy and right to respect of another person. But another prevalent and persuasive theory of civility will insist that such codes of behaviour are all about subjugation: they are visited on people who must be brought to order rather than treated as equals. Thomas quotes the antiquarian Edmund Bolton (born around 1575), who announced that it was “no infelicity to the barbarous” to be “subdued by the more polite and noble”; after all, to possess “wild freedom” meant nothing compared with the gifts from above of “liberal arts and honourable manners.” It isn’t hard to imagine what the wild and free response to that might sound like.

Meet The 26-Year-Old James Beard Award Winner Reinventing Food Writing

Abigail Koffler’s profile of food writer Mayukh Sen, who just won a James Beard award for his own profile of soul food sensation Princess Pamela, is a delightful rabbithole of links. It’s also an interesting look at how even food writing has been politicized since 2016 — which honestly seems much needed when I look back at how many headlines after Calvin Trillin’s awful New Yorker blunder used phrases like “unpalatable for some.” “Some”? Time for some new voices to have their say.

The stories Sen wrote often hinge on experiences that set him apart from the rest of the staff. During a holiday brainstorm at Food52, an essay about fruitcake was floated, with the assumption that “fruitcake sucks.” Unlike the rest of the staff, Sen likes fruitcake. His dad grew up eating it in Calcutta, India and it’s part of the holidays. The dessert is a double edged sword: he’s also been called a fruitcake, a slur against gay people. His essay on the topic explored the usage of fruitcake as a pejorative and the popularity of fruitcake in India. Similarly, an essay about the queer history of kombucha shared the hidden story of a beverage now soaring in popularity.

The Sunday Post for June 24, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Not Caring is a Political Art Form

Rebecca Solnit is going to save our souls by holding up a mirror until we can’t look away. There is nothing the internet does better than provide stories to attract our eyes from the mirror, sometimes such a maze of stories that you can follow it anywhere, land anywhere you want to go. Here, Solnit examines the story of not caring, and where it really leads.

Empathy enlarges us by connecting us to the lives of others, and in that is a terrible vulnerability, one that parents know intimately, terrifyingly. If something happens to someone or something you love, it hurts you too, potentially devastates you forever. The prevention of feeling is an old strategy with many tactics. There are so many ways to really not care, and we’ve seen most of them exercised energetically these last couple of years and really throughout American history. They are narrative strategies and most of them are also fundamentally dishonest.

Dealing With a Book Thief

You know those optical illusions where it flips from a rabbit to an old lady between one blink and the next? This story’s kind of like that: it’s about a man who systematically and comprehensively robbed Little Free Libraries in North Chicago over the course of four months, and depending on where you start, you may end up thinking about how petty and screwed up it is to steal from a library, especially a community-tended Little Free Library. Or you might end up reflecting on how that practice might look rich and indulgent, and thus exploitable, to someone without the resources to imagine painting pretty little boxes and filling them with books.

Still. “Avid reader.” Somebody oughtta clock this guy.

The second time, Richard happened to be home when he saw a van pull up to his Little Free Library book-sharing box. He watched as a man jumped out, took every book out of the Library, and put the books in his car. Richard went out and spoke with him. Richard explained the purpose of a Little Free Library, but the man insisted that he was just an "avid reader," and drove off.

Books Where the Dog Dies, Rewritten So the Dog Doesn't Die

Bonus round! All the stories that made child-you weep uncontrollably (Old Yeller, Where the Red Fern Grows), plus a few that made you weep much later in life, rewritten so the dog lives. Thank you, co-founder Martin McClellan, for knowing our hearts so well.

"Who is this dog?" Odysseus asked at last, smiling through tears

As though he did not know his own pup.

"Who is this good boy?

Who is this good boy?

Who is this good boy?"

The Sunday Post for June 17, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

My Romantic Life

This, by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore, is a glass bullet of a piece that’ll leave shards all through you regardless of where it explodes.

The second time I did porn it was with Zee, when we were boyfriends, and I’d just remembered I was sexually abused, so I was taking a break from sex, but then Zee called me to do the video because his costar showed up too tweaked out — I did it because I needed the money, but then Zee got upset when I couldn’t come, and I felt like a broken toy. Which is how I’d felt with my father. When I walked out into the sun after that first video shoot I just felt totally lost, like I didn’t even know where I was and why was it so hot out, maybe that’s why I felt so dazed.

The Difference Between Being Broke and Being Poor

Erynn Brook (words) and Emily Flake (pictures) have made a softly lacerating visual essay on the distinction between not-having-money-right-now and not-having-money-period. Relevant, unfortunately, to Seattle’s interests.

What If I'm Just a Minor Writer?

Karl Taro Greenfeld had my sympathies from his first line: "I’m not who I was supposed to be." Yet: there are dozens of books by "minor" writers that I read over and over, because they help me survive. Do we all dream of becoming “great” writers (those of us who dream of becoming writers at all)? What’s wrong with just writing well? Or even — just writing?

I dreamed of writing novels that transcended time, that perhaps would someday convince a boy or girl that he or she should become a writer. Like a mother spider who births a thousand spiderlings for only one to survive to motherhood herself, perhaps this is how writers as a species survive. We all dream the same dream, to become important writers. Most of us never achieve it.

A Company Built on a Bluff

Courtesy of Reeves Wiedeman, a crazy-fascinating look at how Vice co-founder Shane Smith sold a particularly bro-centric idea of cool to round after round of investors, transforming an underdog counterculture paper into a media empire. Some of these stories are already well known (like the “non-traditional workplace agreement” and the New York Times investigation into sexual misconduct), but this pulls it all together, and says as much about what media consumption, creation, and investment are becoming as it does about Vice itself.

On the morning of the Intel meeting, Vice employees were instructed to get to the office early, to bring friends with laptops to circulate in and out of the new space, and to “be yourselves, but 40 percent less yourselves,” which meant looking like the hip 20-somethings they were but in a way that wouldn’t scare off a marketing executive. A few employees put on a photo shoot in a ground-floor studio as the Intel executives walked by. “Shane’s strategy was, ‘I’m not gonna tell them we own the studio, but I’m not gonna tell them we don’t,’ ” one former employee says. That night, Smith took the marketers to dinner, then to a bar where Vice employees had been told to assemble for a party. When Smith arrived, just ahead of the Intel employees, he walked up behind multiple Vice employees and whispered into their ears, “Dance.”

Punching the Clock

We’ve all worked a bullshit job — seemingly or truly pointless labor created to fill paid hours. Here’s David Graeber on why the already noxious state of affairs in which another person owns one’s time becomes so much worse when they use it badly.

Most societies throughout history would never have imagined that a person’s time could belong to his employer. But today it is considered perfectly natural for free citizens of democratic countries to rent out a third or more of their day. “I’m not paying you to lounge around,” reprimands the modern boss, with the outrage of a man who feels he’s being robbed. How did we get here?

The Sunday Post for June 10, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

On immigration

Paul Dean on moving across borders, power’s bureacratic sword and shield (remember Papers, Please?), and the diminished dream of freedom in countries built on that ideal. This is a different kind of immigration story, about the authoritarianism trying to hide behind a smokescreen of fear-mongering headlines. Quiet-voiced, gently meandering, will have you by the throat if you follow it through.

Opening the gates is brave. If you open the gates, people come in, and many of those people are different. That’s a scary concept. They might do and want and need different things. If you close the gates, shore them up, raise the drawbridge and fill the moat with hydrochloric acid, you’re much, much safer.

Everything inside is wholesome and good.

Somewhere Under My Left Ribs

Christie Watson on a nurse’s experience of the operating room — not a tell-all, but a meditation on compassion, the connection between body and spirit, and how humans on both sides of the knife manage the terror and pressure of courting death to save a life.

I have looked after such patients, who are told post-operatively that things were a little unstable in theater, but the surgeon managed to stabilize them. The language of nursing is sometimes difficult. A heart cell beats in a Petri dish. A single cell. And another person’s heart cell in a Petri dish beats in a different time. Yet if the two touch, they beat in unison. A doctor can explain this with science. But a nurse knows that the language of science is not enough. The nurse in theater translates “your husband / wife / child died three times in there, but today was a good day and, with a large amount of electricity and some chest compressions that probably broke a few ribs, we managed to get them back” into something that we can hear. A strange sort of poetry.

Anthony Bourdain and the Power of Telling the Truth

Helen Rosner writes about Anthony Bourdain with respect and affection and regret. She celebrates Bourdain not just for his accomplishments, but for his resilience, humility, and willingness to evolve while holding a staredown with the greedy public eye.

Bourdain effectively created the “bad-boy chef” persona, but over time he began to see its ill effects on the restaurant industry. With “Medium Raw,” his 2010 follow-up to “Kitchen Confidential,” he tried to retell his story from a place of greater wisdom: the drugs, the sex, the cocky asshole posturing — they were not a blueprint but a cautionary tale. Ever resistant to take on the label of chef, he published a book of home recipes, in 2016, inspired by the cooking he did for his daughter. Despite its chaotic cover illustration, by Ralph Steadman — and its prurient title, “Appetites” — the book, which was co-written with his longtime collaborator, the writer Laurie Woolever, is a tender memoir of fatherhood, an ode to food as a vehicle for care.

See also PNW writer Tabitha Blankenbiller’s essay on Kate Spade in Salon — you may never carry one of Spade’s iconic handbags, or want to, but this will help you understand why they matter so much those who do.

Climate Change Can Be Stopped by Turning Air Into Gasoline

This is delightfully MacGyver-y: a scientist at Harvard University has hacked together a series of processes used by paper mills to pull excess carbon dioxide from the air and turn it back into previously-known-as fossil fuels. One of my favorite things about this piece is the deadpan quotes from other scientists saying it could work, which seem to be the academic equivalent of throwing your hat in the air with joy.

Speaking from Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Wednesday, Keith said he was “pretty optimistic” about climate change. “The reason is that the market for these low-carbon fuels is much, much better than they were a few years ago. At the same time, low-carbon power — electricity generated by solar and wind — has just gotten much cheaper.”

Outside experts said they were encouraged by Keith and his colleagues’ approach, but cautioned that it would take time to examine every cost estimate and engineering advance in the paper. The consensus response was something like: Hmm! I hope this works!

On The Radio, It’s Always Midnight

Seb Emina on the pleasures of listening to late-night radio any time of day. Somewhere in the world, it’s always midnight — late-night callers, late-night music, a world full of late-night dreams.

Without exception, these late-night conversations meander off into meditations on how things are not how they used to be. This is a function of two truths, namely that (1) in the middle of the night, the caller gets to speak indefinitely because who knows when the next caller will show up, and (2) once midnight has passed, almost anyone who speaks off the top of their head for more than three minutes, on any subject, will stray into nostalgic reverie. In Westchester, New York, for example, a man has called SportsRadio 1230AM at three in the morning to express sadness about the decline of fistfights in stock-car racing.

The Sunday Post for June 3, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

When a Person of Color Tells Conference Organizers Their Conference Is Too White

In February, award-winning Seattle writer and frequent Seattle Review of Books reviewer Donna Miscolta wrote in her blog about attending the San Miguel Writers’ Conference in Mexico. In addition to the marvelous phrase "in a bat of an eye out of hell" (yes) and praise for San Miguel de Allende's beauty, the post includes an account of overwhelming racial imbalance among conference attendees and outright racism in some of the classes.

This week Miscolta published an update describing the conference organizers' response when she contacted them to suggest a different approach next year. The story is told with her trademark directness and precision — Miscolta isn't afraid of emotion, but she knows how to achieve it in other ways than being loud — which makes it easy to imagine the pragmatism with which she would have approached the conversation. And that makes the response from the organizers all the more stunning. Miscolta's advice to them is dead on and valuable for anyone wondering why good intentions alone haven't brought diversity to their platform.

I got a reply the next day, bubbly and breathless in its defense of their desire and efforts to be diverse. She listed all the brown and black people they had featured as keynote speakers over the years. She assured me that the list of general faculty was even more impressive. She described the Spanish-language element of the conference and its Mexican faculty. She expressed regret that “Unfortunately, we receive very few proposals from African American or Asian writers.”

She ended with, “If you know of writers of color whom you can encourage to apply to teach at our Conference, please do encourage them to apply. We need more applications from people of color.”

Could I possibly let this go?

'Once Upon a Time' and Other Formulaic Folktale Flourishes

I know from personal experience (once upon a time) that there is no end of hyperintelligent, hyperscholarly discussion of how fairy tales and folk tales work, including their iconic opening formulae. My hat’s off to Anthony Madrid for aerating those discussions with just the right mix of irreverance and affectionate astonishment. Seriously, this is so much fun, if you have even five volumes of Andrew Lang or just a dozen books edited by Zipes on your shelf …

Forget “upon a time.” Look at the “once.” That part really is standard from the beginning, and not only in English. Just this past weekend, I paged through fifteen volumes of the Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library, and I’m here to tell you: The word once is in the first sentence of almost every single folktale every recorded, from China to Peru. There is some law of physics involved.

Hazardous Cravings

Men feel shame when their bodies don’t fit the social standard, they swallow down those cruel, mocking voices just like women, they destroy their bodies from the inside to make the outside “fit” — all complicated by the expectation that men will be worthy and loveable no matter what their shape (and other myths of masculinity). Alex McElroy tells that story with devastating directness in the setting of a teen job at a Dairy Queen.

I was terrified that the pills would work. Taking one would become taking them regularly, then obsessively, until they snuffed my heart like fingers pinching a flame. But I couldn’t confess this to Boots. Perhaps we weren’t, as I’d liked to believe, enacting some vulnerable version of masculinity but applying its worst expectations — sacrificing our bodies, refusing to care for ourselves — to a traditionally feminine project: becoming thinner. Because as open as we were with each other, we nevertheless refused to acknowledge the damage we caused to ourselves. We couldn’t. We lacked the language to see our sickness as sickness. He could not be “anorexic,” just as I could not be “bulimic.” For men, those words were locked houses.

Icelandic fiction: a family affair

“Any resemblance is purely coincidental” doesn’t hold much water when you live on an island so small that the population approaches dating with a genealogical pre-check. Fríða Ísberg on the peculiar challenges of being a writer (or, more exactly, the family and friends of a writer) in Iceland.

Autobiographical fiction has become widely popular across Scandinavia, and Iceland has proven to be no exception. But Iceland, with its small population, poses unusual ethical problems concerning what one can, and should, write: how does one balance the reputation of real characters against the liberty of the author? And what are the consequences in a country the size of Iceland when a writer, perhaps following the model of Karl Ove Knausgaard, exposes those around them?

Traumatic License: An Oral History of Action Park

You can go see Action Point, the oddball movie about the amusement park geared toward allowing its guests to do maximum bodily harm to themselves, or you can read this amazing oral history of the real park on which the film is loosely based. Owned by Eugene Mulvihill, Action Park was open in Vernon, New Jersey for more than a decade starting in 1983. I mean, this park had rides that put you in the water with snakes and snapping turtles, rides that could break your face, rides that could strip the top layer of skin from your entire body. I can barely choose a quote from this, it’s astonishingly, gloriously ridiculous from start to finish.

Al Rescinio (Guest): It wasn’t like you were armored going down this thing. You’re wearing a T-shirt and bathing suit or shorts. You didn’t know how unstable these little carts are the first time you go on them.

Thomas Flynn (First Aid): The primary ingredient in those tracks was asbestos, by the way.

DeSaye: People would bounce off. That’s why we called them Gumbys. Down in first aid, at the end of the night, you’d be having pizza and inevitably someone would come in looking like they had a giant burn from head to toe.

Benneyan: It was the Action Park tattoo.

The Sunday Post for May 27, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

A Lexicographer’s Guide to Real Words

I agree with Kory Stamper here (“I agree with Kory Stamper” is almost a tautology): unlike the news, there are no fake words. Though I might advocate for declaring some words fake, like “innovation” and “disruptive” and the use of “impacted” to mean “had an effect on.” Irregardless, this is an absolutely splendid opportunity to do that thing we all used to do on the Internet and fall down the rabbithole of clicking all the links in this post that lead to other posts in Stamper’s blog, and then clicking all the links in those posts, and then it’s almost dinnertime and you don’t have your column done but who cares? Kory Stamper!

And even if a word is illogical or stupid, so what? You know how many completely unremarkable words arose from a stupid misreading? You use "cherry" and "apron" just fine, even though "cherry" came about because some 14th-century doofus thought the Anglo-French "cherise" was plural (it wasn't), and "apron" came about because court clerk read "a napron" as "an apron" and rendered it as such, and then future readers thought, "Oh, man, the clerk to Edward III says it's 'apron,' I better get in line," even though that same clerk used "napron" later in the Household Ordinances, and here we are.

What's Going On in Your Child's Brain When You Read Them a Story?

This short piece by Anya Kamenetz is very cool. It offers some real, though preliminary, scientific evidence that reading to your kids is better than plopping them in front of a television set. And it also offers a lens into a part of the brain — the default mode network — that scientific researchers (those romantics!) call “the seat of the soul.” It’s the bit of your mind that’s absolutely farthest from the buzz of social media, the bit associated with self-reflection, daydreaming, and spontaneous thought. Knowing how to cultivate that early and keep it talking to the rest of our overstimulated brains seems like a potentially society-saving discovery.

When children could see illustrations, language-network activity dropped a bit compared to the audio condition. Instead of only paying attention to the words, Hutton says, the children's understanding of the story was "scaffolded" by having the images as clues.

"Give them a picture and they have a cookie to work with," he explains. "With animation it's all dumped on them all at once and they don't have to do any of the work."

Most importantly, in the illustrated book condition, researchers saw increased connectivity between — and among — all the networks they were looking at: visual perception, imagery, default mode and language.

Tech Billionaires Are Building Their Utopias Without Asking Us

The dream of outer space is an expansive dream, big enough to hold intergalactic battles, exploration of the unbearably unknown, and deeply human interactions with deeply alien cultures. Space is The Martian and Star Trek and Ursula K. Le Guin and Sally Ride separated by light years of beliefs and hopes and fears, then tessered back so close they’re almost touching.

The dream of space is expansive, and it’s almost always a dream of something little overcoming something big. It’s not a dream of the richest men on earth claiming outer space as their own personal utopia and throwing up walls of money and power around it. S. A. Applin wonders whether Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk know they’re not, and can’t ever be, the heroes of the space story they’re writing for the rest of us.

We all carry visions of our own utopias, working towards betterment of self, community, or dreaming of an escape. It’s how we focus intent for what we want. The game changes though, when people who have resources can suddenly begin to realize those changes in their Utopian visions, and those visions being realized may begin to conflict with others who have less money and power to realize theirs.

The Sunday Post for May 20, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Slow Pan

This essay by Bryan Washington is remarkable. It’s a poignant personal essay about growing up gay and black and how movies showed him a possible self, even in times and places where that self was terrifying and dangerous. It’s a record of how cinematic representation of being queer and black has evolved, and how the way we see such films is evolving too. And it’s an unrefusable demand to keep telling and filming and printing and promoting stories that aren’t the dominant narrative. Those stories are lifelines. They’re weapons. They’re the signals that can, eventually, overcome the noise.

The audacity required to ask if we need another gay movie, if we need any more gay movies, transcends thinking altogether. It is a thoughtless question. You only ask it if you’ve seen yourself so ingrained into the culture, into the fabric of the world, that your absence from those seams is unthinkable. You only ask that question if you’ve never been repulsed by yourself, or the idea that anyone like you, anywhere, could be happy. You only ask that question if you don’t know what it means to feel like the only person on the planet.

The Poetics of Petfinder: A Tale of Accidental Adoption

If you’re a dog or cat up for adoption online, something’s gone badly awry. You used to be cared for; now you aren’t. And everybody knows you’ve been dismissed from your position, maybe with cause.

So the people who write descriptions for Petfinder have a tough job: to show us how we could love something that seems unlovable, and convince us that all dogs are good dogs one way or another. Here’s Andrea DenHoed with the story of how Petfinder hooked her, hard, on a tiny chihuahua with a bad attitude and a big heart.

Behold the lopsided ears! Behold the scraggly coat! Behold the lolling tongue, the malformed limb, the crooked tail! Each creature is held up for careful consideration, and each is declared worthy. This is the look of love in the Corinthian sense, patient and kind and keeping no record of any pup’s wrongs.

An Open Letter About Female Coaches

The assistant coach for the San Antonio Spurs is Becky Hammon, the first woman to be hired as a full-time assistant coach for the NBA, the NFL, the MLB, or the NHL. When a rumor surfaced that Hammon was being interviewed for a head coach position — just interviewed, not hired, not even a frontrunner — sports exploded. Pau Gasol plays for the Spurs; he’s a six-time NBA All-Star and a four-time All-NBA selection, which I assume is very good. His insider takedown of the arguments against Hammond is so lovely: straightforward, perfectly pitched, and totally unambivalent about giving women the roles they deserve, no exceptions.

Let’s be real: There are pushes now for increased gender diversity in the workplace of pretty much every industry in the world. It’s what’s expected. More importantly — it’s what’s right. And yet the NBA should get a pass because some fans are willing to take it easy on us … because we’re “sports”?

I really hope not.

The coup has already happened

If you are dizzied by the pace, insanity, and sheer volume of the news cycle these days (ha ha ha! I’m kidding! of course you are!), turn to this, by Rebecca Solnit. Block by excruciating block, she stacks together all of the stories scattered by Hurricane Trump’s tweet-driven wind. There’s already been a coup in America. And while we’re waiting for something that’s already here to arrive, we’re letting our country be gutted from the inside out.

After the coup, everything seems crazy, the news is overwhelming, and some try to cope by withdrawing or pretending that things are normal. Others are overwhelmed and distraught. I’m afflicted by a kind of hypervigilance of the news, a daily obsession to watch what’s going on that is partly a quest for sense in what seems so senseless. At least I’ve been able to find the patterns and understand who the key players are, but to see the logic behind the chaos brings you face to face with how deep the trouble is.

The Sunday Post for May 13, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

(MORE) guided journalists during the 1970s media crisis of confidence

(MORE): A Journalism Review ran from 1971 to 1978, tweaking the nose and stepping on the toes of mainstream journalism, running stories the big names spiked and saying why. Sometimes the tweaks were juvenile, like compiling a raft of “bus plunge” stories from the New York Times. But often (MORE) brought real news to light and at the same time reminded mainstream media that their peers were watching. Kevin Lerner’s history of the publication is packed with great stories and thoughtful reflection about the role of the journalism review in today’s embattled media landscape.

In ways that echo the 1970s, American journalism is facing a crisis of confidence once again, and the most self-aware journalists are beginning to critique themselves as much as their audiences are. The current model of journalism is again struggling to adequately describe the world it is trying to cover. The best minds in journalism can find each other easily now, but another (MORE) needs to finish the job it started — to make the press more self-aware, more self-critical, more flexible, and better able to rethink its best practices in the face of its own failure.

We Need More Non-Binary Characters Who Aren’t Aliens, Robots, or Monsters

Sharp observations from Christine Prevas about how sci-fi uses nonbinary gender to emphasize the non-human nature of non-human characters — and what that means for very human nonbinary readers.

Here, in a novel that isn’t about gender, a character is calling attention to the aching lacuna left by the binary question, “are you a boy or a girl?” They are finding an alternative answer. When Soro answers, I’m a Sunai, they are finding a new way to answer the question.

I’ve answered the question this way, too. A young child at my place of work once asked me: are you a boy or a girl? I panicked and answered: I’m a librarian. Can I help you find something?

For Libraries, "the Customer Is Always Right" Might Be Wrong

One thing’s clear in this feisty short essay by librarian Kristen Arnett: patrons should never be allowed near the copy machine. On the challenge of keeping end goals in mind while working on the front lines of circulation.

Circulation is the face of the library. It’s a public-interaction job, which means customer service, which means you better be able to smile at someone even if they’re yelling about how they broke the copy machine by sticking newspaper in the feed tray “just to see what would happen.” It’s a glamorous gig, circulation, and so much of it is dealing with people getting pissed off because they can’t have the thing they want exactly when they want it.

"We are New York indie booksellers"

Franck Bohbot’s portraits of New York’s independent booksellers (taken with partner Philippe Ungar, whose interviews will be published alongside the photographs in a forthcoming book) are careful and quirky. These aren’t Instagram-friendly images of smiling booksellers with piles of gleaming stock; the photos are oddly lit and oddly proportioned, serious, almost somber. Bohbot captures the pride these booksellers take in their stores — and the weight of running a small, stubborn business in an industry crowded by Goliaths.

The spectacular power of Big Lens

If you thought Big Tech was creepy, meet Big Lens — the newly minted megacompany that’s mediating the way we see the world.

Over the coming decades, EssilorLuxottica will have the power to decide how billions of people will see, and what they can expect to pay for it. Public health systems are always likely to have more urgent problems than poor eyesight: until 2008, the World Health Organization did not measure rates of myopia and presbyopia at all. The combined company can choose to interpret its mission more or less however it wants. It could share new technologies, screen populations for eye problems and flood the world with good-quality, affordable eyewear; or it could use its commercial dominance to choke supply, jack up prices and make billions. It could go either way.

The Sunday Post for May 6, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

I tried to warn you about Junot Díaz

Regrettably, I highlighted Junot Díaz’s New Yorker article about his childhood rape here a couple of weeks ago. This week, I’d like to give equal space (and wish I could give more) to the writers who have spoken out about their experiences of harassment and misogynistic treatment by Díaz — Zinzi Clemmons, Carmen Maria Machado, and Monica Byrne among them.

Why do I regret sharing Díaz’s piece? Not just because I gave air space to a man who used his power badly, but because I helped disseminate a story that will be used, is already being used, to create understanding and empathy for his appalling behavior toward women. In that New Yorker piece, Díaz claimed his personal story as one of the wounded; in marketing terms, he controlled his narrative. But let’s be clear: No amount of trouble justifies, excuses, or ameliorates doing harm to others.

On her personal blog, essayist, novelist, and producer Alisa Valdes tells her own Díaz story, which is also a story about how the writing of women, and of women of color, is read — and especially about how the literary establishment grants prestige and power. What it highlights is the full extent to which belief takes the side of the powerful. And the full extent of the damage that does.

Things were hard. Harder than they should have been. People posted about how "crazy" I was. Truly vile and abusive shit. I had become a writer in part because I am an introvert. I never wanted the attention to be on me as a person, only on my writing. But there I was, being dragged through the mud. I was named one of the 25 Most Influential Hispanics in America by Time magazine because of my books, but still could never get a call back from the New Yorker, or the NY Times, when I pitched poems or stories or op-eds. Maybe it was Diaz. Or maybe it was something else. My vagina. My book covers. My lack of an MFA. My honesty. My unwillingness to write in a way that made white liberals feel sorry for me while admiring me.

Treated Like Trash

Kiera Feldman reports the story of a young immigrant who died working what might be one of the hardest and most dangerous jobs in the country: collecting garbage in New York City. After Mouctar Diallo was killed by the truck on which he served as a “third man” — an under-the-table addition to the standard crew — the driver denied knowing Diallo to avoid blame for the death. A heartbreaking and fury-inducing installment in ProPublica’s ongoing coverage of corruption in New York’s garbage industry.

The truth of Mouctar Diallo’s death is that the authorities investigating the accident did not learn that he was a worker on the truck for at least two months, and that when they did, they took no action against the driver and helper who had lied to police. The Business Integrity Commission, the New York City agency charged with oversight of the commercial garbage industry, allowed both the driver and main helper to keep working. The police and Bronx prosecutors closed their investigation with no criminal charges.

E-Books, Accessibility, Luddites, and the Techno-Dazzled

I still remember the first time a doctor handed me a tissue, to catch the tears he predicted (wrongly), before telling me what he saw in the back of my eyes. As my sight has degraded less-than-gracefully over the years, my brain compensates. I know what f—k means. I know what “I —ve y—” means. If I can’t see recto and verso together, I can see each in turn. And although my eyes are slowly unlearning how to read — at least, to read as they have for most of my life — there are now so many other ways to read, and write, than on a printed page.

So I appreciate M. Leona Godin’s smart, smart take on attitudes toward e-readers and how that translates when an electronic book is the only kind of book that's accessible. Her new column for Catapult on blindness and writing and reading is more than worth following — great writing “with a badass attitude” (as she describes Jim Knipfel) about how vision impairment affects a life dedicated to words.

This is my point: Blind and print-handicapped readers do not have the luxury of deciding whether they will go old-school and deny the digital age. Braille books and audiobooks have limited publishing potential built-in because of their high production costs, but when it comes to publishing electronically, it’s the attitudes rather than the costs that are limiting.

‘No Company Is So Important Its Existence Justifies Setting Up a Police State’

It was always a coin toss, right? Whether our science fiction future was going to be Transmetropolitan or flying cars?

Actually, let me take a step back. Calling something "science fiction," whether happy or scary, implies it's not real. And it's time to stop thinking about the invasion of our privacy and the decimation of our economies, whether it's by tech giants or simply enabled by them, is the future or a fiction. This is our ordinary now, our daily reality. It's time to start responding like it matters.

Here's a piece by legendary programmer Richard Stallman, someone who knows the industry from the inside out, on the legal and behavioral shifts that need to happen to protect the privacies, political freedoms, and jobs under threat. Great read overall, but if you don’t have time, here’s one thought to walk away with:

Fuck them — there’s no reason we should let them exist if the price is knowing everything about us. Let them disappear. They’re not important — our human rights are important. No company is so important that its existence justifies setting up a police state. And a police state is what we’re heading toward.

The Sunday Post for April 29, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Whose Story (and Country) Is This?

Rebecca Solnit reframes America’s ideological churn as a battle over story — not who tells it, but for whose benefit it’s told. It’s a very Solnit-y clarifying lens on something insidious: our willingness to worry over the men held to account by the #MeToo movement, our willingness to cosset men whose views toward other humans are simply reprehensible, our immense discomfort with the discomfort of white men. At a far extreme, this is the narrative of the incels; to be prevented from taking their place at the center of the story is so violent to their egos that it justifies real and deadly violence to others.

The common denominator of so many of the strange and troubling cultural narratives coming our way is a set of assumptions about who matters, whose story it is, who deserves the pity and the treats and the presumptions of innocence, the kid gloves and the red carpet, and ultimately the kingdom, the power, and the glory. You already know who. It’s white people in general and white men in particular, and especially white Protestant men, some of whom are apparently dismayed to find out that there is going to be, as your mom might have put it, sharing.

It may seem like a forced tie-in, but it’s hard not to draw a connection on the day after Independent Bookstore Day: Cultivating independent bookstores and independent literature written by people who have other stories to tell might, perhaps, be a useful thing to do?

The Ben Duncan and Dick Chapman Papers Come Out

Ben Duncan was an American student on fellowship at Oxford University when he met Dick Chapman. Chapman was British, shared a love for literature, shared left-leaning politics. When Duncan and Chapman fell in love, their relationship was not just unacceptable but illegal. In 2005, five decades after they met, they became one of the first gay couples to register as civil partners in England.

One of the joys of bibliography is seeing how the making of books tells as much of a story as their contents. Duncan’s autobiography, The Same Language, charts changing public and political opinion in what subsequent editions reveal. Similarly, a collection of letters between the two men — donated to Columbia University Libraries in 1990 but closed to researchers until after both of their deaths — says much even in how it was stored. A blog post from the library tracks the progress of the collection, including how librarians helped Duncan and Chapman keep their secret until they were ready to tell it.

Calling the collection the Ben Duncan and Dick Chapman Papers might have been too obvious, but the addition of Duncan’s manuscripts allowed it to be presented as Duncan’s papers alone. Thus the collection’s original name: the Ben Duncan Papers. The collection’s original summary likewise hinted at the importance of the letters without giving anything away. The archivist wrote, “The correspondence consists chiefly of letters between Duncan and Richard Chapman, during 1956 and 1957, when Duncan, an American, was working in advertising in England, and Chapman, an Englishman, was working in advertising in New York. These letters provide a perspective on daily life during the mid-1950s, including such topics as books, plays, current events, and customs of that period.”

How the Trump Show Gets Old

We’ve had plenty of comparisons between the Trump presidency and his reality-television career, so kudos to Michael Kruse for finding an angle worth exploring: the similarity between the arc of Trump’s political career and the win-lose-win arc of his entertainment (and real estate) career. You may not feel like you need to know more about Donald Trump — likely you wish you knew less. Still, this is an interesting detailed look at how Trump handles failure, and especially how he manages to paint himself with success while the ship goes down beneath him. That he might do so again in 2020 is a possibility we can’t afford to ignore. Sadly.

The relentless decline of “The Apprentice” reflects a splash-and-crash cycle that’s been a hallmark throughout Trump’s life — from his buildings to his casinos to even his brief stint as a sports team owner. His initial successes are often followed by reckless decisions to double down on his bet, just to keep the excitement going — with often disastrous results. “It’s true of everything he goes into,” Trump biographer Tim O’Brien said in an interview. “He will hunker down and do something well — and then he thinks he’s Zeus.” And that’s when the trouble starts. “Because he’s not Zeus.”

The Sunday Post for April 22, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Old Friend

Poet, translator, and activist Press Sam Hamill died last week. The AP obituary recaps the public story of his life: He was raised in Utah and found a calling for poetry in San Francisco, after rough teen years marked by heroin addiction and violence. He co-founded Copper Canyon Press, with Hugo House’s Tree Swenson and Bill O’Daly, in 1972, establishing a PNW publishing presence that drew names as big as any coming out of the New York houses. He was outspoken and anti-war, famously refusing an invitation to the White House from Laura Bush in 2003 — this irritable article from the time by Joseph Bottum is a reminder that poets can get under our nation’s skin.

That’s the public story. The private story is playing out over hundreds of recollections of Hamill’s influence on his friends and writers here in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. These seem, somehow, a better representation of what he really achieved. For example, the verse tribute by Hamill’s friend Paul Nelson in Cascadia Magazine, whose opening lines I’ll excerpt here:

We wander through asphalt riparian zones

until it hits each of us: it IS later than we thought.

Another quick trip between this veil of soul-making

and complete re-calibration to the ultimate mystery.

How much is a word worth?

Malcolm Harris charts the declining pay for freelance writers — not just the up-and-comers paying their dues, but writers at the top of their game, selling pieces to internationally known publications. Without any way to influence rates collectively (or health insurance, which I hear is a good thing to have) many move on, to television, for example, or other in-house jobs that use the same skills to an arguably less noble end. But the brilliant little bit of math below shows the more insidious outcome: the calibration of quality to pay, with a decrease in one correlating directly to the other.

I was assigned this story at $4,000, and I turned in a draft of 4,000 words. Another site offered me $850 for the idea, and there is an $850 version of this story that is significantly shorter, with less research, and of a weaker quality overall. (If that sounds cold or unprofessional, imagine what the effect on the quality of your work would be if your boss cut your pay by 80 percent.)

There is also a $2 a word version that has more background research—in physical, not just digital archives—and for which I would have been more willing to press my sources to take risks and talk to me on the record.

I imagine a $4 per word version would include the specific, surprising allegations about the labor practices of particular beloved media institutions, the printing of which likely would make it difficult for me to find work for a while, but that would be fine, because I could live off that check for six months.

"One Has This Feeling of Having Contributed to Something That’s Gone Very Wrong"

New York magazine has been running a series of interviews called “The Internet Apologizes” — reflecting our belated realization that trusting a vast uncanny technological network with our emotional, social, and financial well-being was perhaps not such a great idea after all. This one, with virtual reality pioneer Jason Lanier, is interesting (if a little reactive) for how it charts the the social and economic stratification of the tech-nerd class. What happens when the formerly powerless suddenly own the world?

When you move out of the tech world, everybody’s struggling. It’s a very strange thing. The numbers show an economy that’s doing well, but the reality is that the way it’s doing well doesn’t give many people a feeling of security or confidence in their futures. It’s like everybody’s working for Uber in one way or another. Everything’s become the gig economy. And we routed it that way, that’s our doing. There’s this strange feeling when you just look outside of the tight circle of Silicon Valley, almost like entering another country.

The Sunday Post for April 15, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

I saw this on an OS map and couldn't not investigate

Knowing the names of things matters. In this charming thread by @gawanmac, naming strengthens and grounds a series of haunting images of the British woods, transforming the merely atmospheric into something much better. The result is what might happen if Instagram merged with Infocom; you wouldn’t think anything good could come of that, but here we are.

I saw this on an OS map and couldn't not investigate. A place of worship symbol in the middle of bloody nowhere on the edge of a wood. It was a foggy, atmospheric day up on the North Downs, so I decided to walk three sides of a square through the wood to reach it. pic.twitter.com/R47CTs9Mg2

— gawanmac (@gawanmac) April 13, 2018

Maybe something

Tamuira Reid’s elegy for her dying father is crushing, but you should read it anyway, even if you have to take multiple runs at it like I did. Because it’s blazingly good writing. Because hard stories told well deserve it.

Because swim meets and tap recitals and science fair projects. Because popcorn in olive oil. Because walks by the ocean. Because you let me put my skates on. Because you didn't spank us even when she wanted you to. Because Neil Diamond said turn on your heartlight. Because what is heartlight? Because I am your daughter. Because you are so thirsty. Because the doctors say no water. Because fluid in your lungs. Because cancer.

(h/t Matt Muir of Imperica’s Web Curios newsletter)

How do we write now

Patricia Lockwood on writing in the time of Trump: halfway between poem and prose, acid and wry, hopeless and hopeful.

The first necessity is to claim the morning, which is mine. If I look at a phone first thing the phone becomes my brain for the day. If I don’t look out a window right away the day will be windowless, it will be like one of those dreams where you crawl into a series of smaller and smaller boxes, or like an escape room that contains everyone and that you’ll pay twelve hours of your life for. If I open up Twitter and the first thing I see is the president’s weird bunched ass above a sand dune as he swings a golf club I am doomed. The ass will take up residence in my mind. It will install a gold toilet there. It will turn on shark week as foreplay and then cheat on its wife.

English will come out of it wrong, and then English will come wrong out of me.

(Did you notice this line — “learn the names of trees”? If you skipped the first piece in today’s Post, go back to it now. That’s why.)

The Silence

Junot Díaz has in some sense been writing about being raped as a young boy since his first published story. But this widely shared New Yorker essay is his first open statement — an accounting and an apology, in an epistolary form that creates a private space on a very public page.

I know this is years too late, but I’m sorry I didn’t answer you. I’m sorry I didn’t tell you the truth. I’m sorry for you, and I’m sorry for me. We both could have used that truth, I’m thinking. It could have saved me (and maybe you) from so much. But I was afraid. I’m still afraid—my fear like continents and the ocean between—but I’m going to speak anyway, because, as Audre Lorde has taught us, my silence will not protect me.

X —

Yes, it happened to me.

The Sunday Post for April 8, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Comic book artist worked on Wonder Woman & Thor, now homeless

There’s not much new in this Weekly Standard article on homelessness in Seattle for any resident of “this picturesque city nestled on Puget Sound” (ahem) who’s paying attention. Still, it’s a good stop against complacency, to see ourselves through an outsider’s eyes — and especially the casual mention of Seattle’s “energetic NIMBY movement.”

For book lovers (that's you), this piece by Ryan Krull on the intersection between libraries and homelessness in St. Louis is also interesting, especially in the wake of the recent sharps waste kerfuffle at Seattle’s library system. There’s a NIMBY element hidden in both, if you look close enough. (Spoiler: you don’t have to look that hard.)

And here’s one last angle: award-winning comics author William Messner-Loebs, one of the artists credited in Wonder Woman, is homeless, thanks to a string of bad luck and the absence of any reasonably functioning safety net for writers and artists. Derek Kevra wrote about his love for Messner-Loebs’ work. I don’t have a neat takeaway for this one (though I bet co-founder Paul Constant does), except to say that all three of these pieces reflect a misplacement of values that might be worth taking a cold hard look at — before it’s too late for us to make a different choice.

I don’t remember 6-year-old me reading that story line, and I don’t remember how Dad handled it (Bill was curious about this) but I remember the cover. And I remember his name on it.

I sat there in silence for a few minutes.

I don’t know what I was hoping for but seeing his name hit me like a ton of bricks. Those comic books created some of my favorite memories as a kid and Bill wrote them. He created, fought for and worked on those stories and I read them with Dad while drinking a Cherry Pepsi.

Now the man who gave me those memories was living out of his car. I’d love to say at that moment I jumped up with a specific plan to help him get on his feet but in reality, I sat there and cried.

Dark Matters

Abe Streep’s profile of the Arlee Warriors, the championship-winning high school basketball team from the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana, has gone everywhere this week. It’s a pretty piece: inspirational, touches on some tough issues, lightly. It makes us sad in that way that we’re all okay with — the non-bleak, mostly hopeful, bearable kind of sad.

Which is a bit of a tipoff that the ways in which Alicia Elliott’s essay about Canada’s failure to convict the adult/male/white killers of two Indigenous teenagers makes you feel sad may not be bearable. Her central metaphor — racism as the unseeable thing that deforms the universe we live in — is apt and powerful, and her writing is personal and relentless. This deserves to be read just as widely, starting with you.

Then I remembered what Gerald Stanley’s lawyer said about Colten’s death in his closing argument: “It’s a tragedy, but it’s not criminal.” I remembered the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities trying to push for stronger self-protection laws while simultaneously denying the impact the Boushie killing had made on this decision. I remembered the white people on Twitter flooding Indigenous people’s accounts with racist slurs; claims that Stanley was acting in self-defence; claims that Colten was a criminal who had it coming; that Stanley’s white lawyer dismissing all visibly Indigenous people from the jury as soon as he saw them was not racist; that an all-white jury finding Stanley innocent of any wrong-doing when he shot Colten point-blank in the head was not racist; that none of this was racist. I remembered all the times I’ve pointed out racism in my life and the white people around me claimed I was imagining it. I remembered that, eventually, I started to wonder if I really was imagining it. I am always made to feel as if I am imagining it.

The Rules of the Asian Body in America

Finally, one from Roxane Gay’s new venture, the month-long pop-up magazine Unruly Bodies: Matthew Salesses on what happens when his Korean wife is diagnosed with stomach cancer after the birth of their second child. While the safety net of American health insurance shreds beneath her, the new and uncertain immigration laws tangle themselves around the family’s neck.

(Full disclosure: clicking this link will burn one of your three free reads on Medium this month. If you care about that sort of thing.)

I was among the largest wave of Korean adoption in the late 1970s and early 1980s. My adoptive parents are Catholic. (My father was on his way to becoming a priest when he married my mother.) They believed the best way to be good Christians was to erase my body from contention. According to my father, they still consider me not Asian at all, “only their son.” In order to follow the rules of family, my body had to be an exception to the rules.

It was in search of my body and its rules that I found Cathreen in 2005, when I went to Korea believing that I had no history at all. She introduced me to myself. Four years later, she immigrated to America, married me, and got her green card, putting her trust in rules that historically distrusted us.

The Sunday Post for April 1, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Ten Times Gravity

Reading this essay by Richard Chiem is like being run over by a very gentle freight train; there’s a vibration on the tracks, then suddenly you’re aflight — slightly stunned, wondering how something that looked far off got so close so fast. He’s talking about confidence, about childhood, about cruelty, about love, and in every paragraph he fixes himself and his reader to a point, then quietly flips it and leaves you both spinning. Hard to excerpt, especially because every paragraph’s so carefully crafted and so very much of its place; just click the link.

I ghost at parties because I’m a ghost inside. You will never know it, but I’m reanimating myself right in front of you, all beneath the surface, because I am too much in my own head. I am thinking what to say, how to say it. I am thinking how much it takes to be in a room. It takes so much to be in a room.

My mother, unfortunately, was a cruel person, and my childhood, unfortunately, was her masterpiece. I am made from mostly water and one hundred thousand beatings. I am made of hyperbole and perhaps one hundred dozen beatings.

Letters: Iris Murdoch

Sometimes you just wake up in an Iris Murdoch mood, you know? Maybe you have time for this conversation between biographer James Atlas and Murdoch, from 1990. Or if you’re nearing the bottom of your coffeecup, try this tiny collection of letters from a young Murdoch to Raymond Queneau, an older and then more successful writer, in which she wields her stunning mastery of language to express all the glorious awkwardness of a literary crush.

If the devil were bargaining with me for my soul, I think what could tempt me most would be the ability to write as well as you. Tho’ when I reflect, in my past encounters with that character he has not lacked other good bargaining points ...

The year in Trump novel pitches

Literary agent Erik Hane reads his slush pile like it’s tea leaves for the state of society.

. . . no matter the state of the world, the truly great manuscripts will always be a small fraction the slush. That’s publishing. But if you want a window into the collective state of our writing lives, it’s not the successes that do the revealing — it’s the far larger, unseen body of attempts, false starts, and misshapen Trump novels that reveals that something inside us has been knocked off its axis.

When the Heavens Stopped Being Perfect

Sometimes it’s better not to see the things we love too closely. Alan Lightman on how we lost the perfection of the stars.