Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from September 24th - September 30th

Monday, September 24: Teaching for Black Lives Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, 104 17th Ave S. https://www.langstonseattle.org/, 7 pm, $5.Tuesday, September 25: Chain Letter

The most continuity-obsessed reading series in Seattle continues tonight with poet Willie James, multi-hyphenate writer and open mic host Kate Berwanger, and poet Morris Stegosaurus. The reading will be followed by an open mic. Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, http://vermillionseattle.com, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, September 26: The Dead Reading

BookForum describes Swiss novelist Christian Kracht's The Dead as "like a reboot of J. G. Ballard’s Crash, in a treatment by Wes Anderson, after a weekend spent binge-watching John Schlesinger’s version of The Day of the Locust." That's, uh, a lot of comparisons.Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Thursday, September 27: South Asian Writers of the Pacific Northwest

Help the Hugo House celebrate its first week in operation since moving back home with a passel of local authors including Jordan Alam, Sasha Duttchoudhury, Jasleena Grewal, Shankar Narayan, and your host Sonora Jha. Hugo House, 1634 11th Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org, 7 pm, free.Friday, September 28: Brave New World

The first Hugo Literary Series event in the House's new space happens tonight. If it's been so long that you've forgotten the deal: three writers (including at least one nationally known author) and one musician compose new work on a theme. Tonight's theme is "Brave New World" and the artists are writers Jim Shepard, Cedar Sigo, Sabina Murray, and musician Anhayla. Hugo House, 1634 11th Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org, 7:30 pm, $25.

Saturday, September 29: The Dark Descent of Elizabeth Frankenstein Reading

It's almost October, which means it's time for creepy stories. This afternoon, Kiersten White reads from her novel that expands on the perspective of a young woman in the Frankenstein story. The Dark Descent of Elizabeth Frankenstein is in some ways a reconsideration of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's legacy. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 5 pm, free.

Sunday, September 30: Dreamers Reading

Children's book author Yuyi Morales brings her new picture book memoir to town. It's a story about how she moved to the United States from Mexico in 1994 with nothing but some dreams and a baby in her arms. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Teaching for Black Lives at Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute

Last week, Macklemore announced that he was teaming up with NFL player Michael Bennett to buy copies of Teaching for Black Lives for "every middle and high school Social Studies and Language Arts teacher in the Seattle Public Schools." It's a breathtaking announcement, a sweeping endorsement that provides the kind of spotlight that only celebrity can offer.

Coedited by local educator Jesse Hagopian, Teaching is a book that calls for educational reform on just about every level. It seeks to replace the current systemic erasure of Black students with a curriculum that values and celebrates Blackness. By raising awareness of stereotypes and encouraging community conversation, Hagopian and the other contributors hope to upend the way racism is taught in our schools.

No single book can fix a system that has largely gone unexamined for decades, of course. But Teaching raises awareness of a situation that too many educators don't even realize exists. It's an important first step toward breaking a chain of violence that stretches back further than the origins of this country.

The reading tonight, which features readings from and discussions of the book, is sold out, but there will be a standby line on a first-come, first-served basis. Go see why this is a book that is about to change this city for the better.

Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute, 104 17th Ave S. https://www.langstonseattle.org/, 7 pm, $5.

The Sunday Post for September 23, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Alone with Elizabeth Bishop

Biographies of Elizabeth Bishop have always been both necessary reading and an unwanted intrusion for me. I believe this is true for many who connect with the deeply private poet’s work — our affection drives competing desires to know her better, to protect her from being known, and to know her only as we know her, without the necessary intrusion of the biographer’s voice.

So I love and respect Gabrielle Bellot’s ability to reclaim a personal relationship with Bishop in this essay, which draws on Megan Marshall’s revelatory recent biography without being overwhelmed by the biographer’s narrative. A beautiful short piece about how being good at being alone can be a survival skill, especially for those whose selves are unacceptable to the mores of their time.

In the worlds I imagined, I was a girl with another girl — or, once in a while, a boy — at my side. In my time alone, I learned to sail away, as Bishop did, to an elsewhere-place — and sometimes I think I would not have survived if I had not had the outlet of my alone time, my imagination. My solitude nourished my writing, and writing often helped me cope, but it couldn’t take away my depression from feeling that I was living an ugly lie. At my lowest point before coming out as trans, I was about to end my life by drinking poison — and then, unlike Bishop, I decided I had to take the risk of openly living my truth. I came out in my mid-twenties, having chosen to stay in America rather than return home, since America, at least, seemed to offer me a chance to live as that woman-loving woman of my constant dreams. But without what Bishop identified, the deep saving grace of quietude, I doubt I would have lived long enough to come out at all.

No, I Will Not Debate You

After The New Yorker banned Steve Bannon from its festival, The Economist faced public pushback when they invited Bannon to their Open Future Festival. In the end, they stood by their man, and lost several woman panelists, including Laurie Penny, because of it.

Characteristically, the internet indulged in endless hand-wringing about both invitations and both decisions. Characteristically, Penny cuts right through the noise.

Steve Bannon, like the howling monster from the id he ushered into the White House, exploits the values of the liberal establishment by offering an impossible choice: betray their stated principles (free, open debate) or dignify fascism and white supremacy. This weaponizes tolerance to legitimize intolerance. If we deny racists a platform, they feed off the appearance of censorship, but if we give them a platform, they’ve also won by being respectfully invited into the penumbra of mainstream legitimacy. Either way, what matters to them is not debate, but airtime and attention. They have no interest in winning on the issues. Their image of a better world is one with their face on every television screen.

Some interpersonal verbs, conjugated by gender

This, by Alexandra Petri, is a furious and brilliantly mimetic examination of assault, privilege, and weaponized grammar.

It happens. It happened. It was a long time ago.

She waits. She says nothing.

She should not have waited. She should not have said nothing.

She remembers it happened. She remembers it happened to her. She remembers he did something.

She says something.

The Brilliant, Playful, Bloodthirsty Raven

Helen MacDonald, author of H Is for Hawk, reviews Christopher Skaife’s account of his work as ravenmaster of the Tower of London. Full of tasty corvid gossip and playful bloodlust, with a bit of history and politics to hold it all together.

Skaife calls attention to the birds’ beautiful contradictions. In sunlight their dark feathers shine with the iridescence of oil on water. They can be friendly, curious, even loving. In the wild they’ll take turns sliding down snowbanks and make toys out of sticks. At the Tower they play games of KerPlunk, pulling the straws free from the tube to retrieve a dead mouse as their prize. Yet, as that special raven edition of KerPlunk suggests, they’re also birds of gothic darkness and gore, the birds that followed Viking raiders in quest of fresh corpses and that feasted on executed bodies hung from roadside gibbets. You might visit Skaife’s charges in the Tower and watch, entranced, as they gently preen each other’s nape feathers, murmuring in their soft raven idiolect — but you might also see them gang up to ambush a pigeon and eat it alive.

The Disappeared

On a very different note, Hannah Dreier reports this week on the serial gang murders of teenagers in Long Island’s immigrant community — largely without interference by the police, who called the crimes “misdemeanor murder.” Carlota Moran is the mother of one of the dead children, her son Miguel tricked into the woods and then slaughtered with a blow to the head and a machete. For months she looked for Miguel, and for help from any public agency, facing if anything active resistance from the local police. Then the gangs killed two girls from the rich side of town.

The murders made national news. Trump hailed the girls’ parents and invited them to his State of the Union speech. The Suffolk County Police Department came under intense pressure to solve the case. It posted signs offering a $15,000 reward for help catching the killers. Officers went door-to-door asking for tips. Over the summer, Suffolk officials had rejected an offer to start an anti-gang program for immigrant teenagers in Brentwood, according to two people familiar with the episode. Now, they called the organizer back and asked how soon she could get it running. Police arrested dozens of suspected MS-13 members and mapped out the local cliques. Within days, they were searching the woods with German Shepherds and shovels.

Whatcha Reading, Somaiya Daud?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Somaiya Daud is a Seattle-based writer and PhD student. Her first novel, Mirage, was just released in August by Flatiron Books. She'll be appearing at the Portland Book Festival in November, which by itself is a great reason to plan a trip south, but with Daud appearing, you can go and cheer on Seattle talent while living your best PDX life. Sounds like a great little getaway!

What are you reading now?

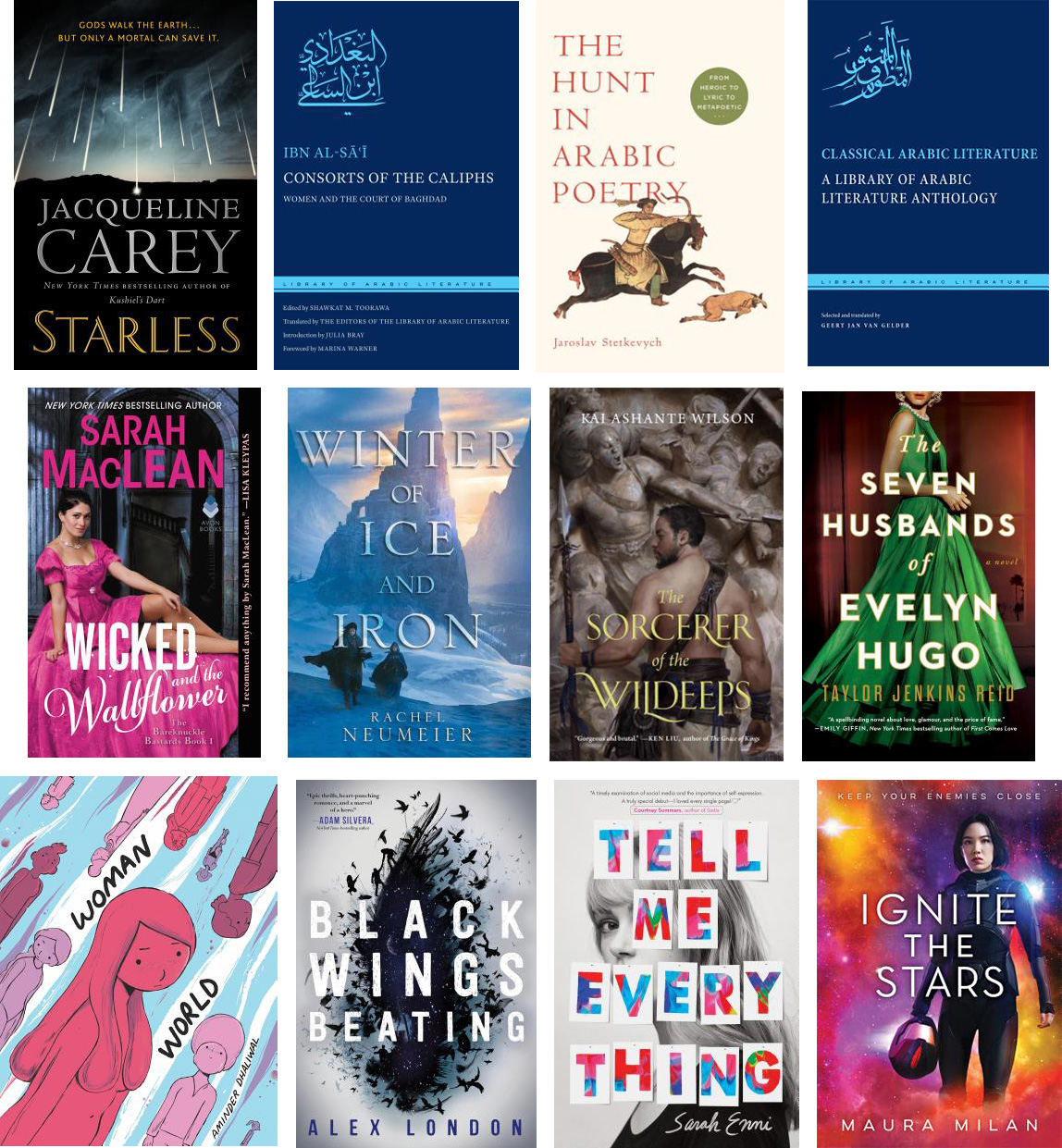

I have been in the mood for a lush, sprawling fantasy so I just checked out Jacqueline Carey's Starless and I keep starting then pausing my re-read of her older Kushiel books. I'm also doing a lot of research reading for the second Mirage book and that includes Consorts of the Caliphs by Ibn al-Sa'i, The Hunt in Arabic Poetry by Jaroslav Stetkevych, and selections from Classical Arabic Literature, a curation put together by Geert Jan Van Gelder.

What did you read last?

I just wrapped up Sarah Maclean's Wicked and the Wallflower, and finished a reread of Rachel Neumier's Winter of Ice and Iron.

What are you reading next?

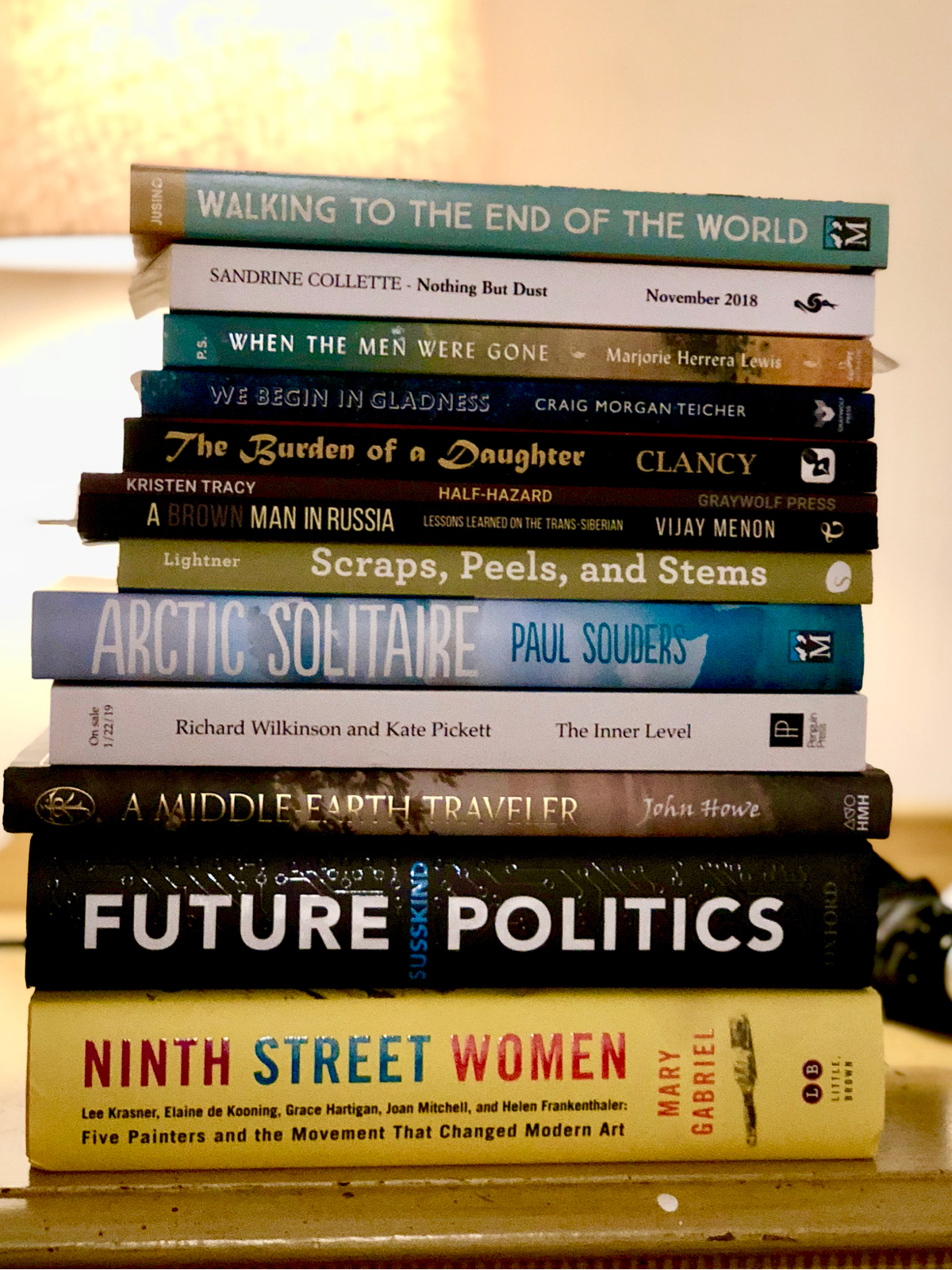

I have quite the stack! I'm planning on rereading Sorcerer of the Wildeeps by Kai Ashante Wilson! My new reads stack is currently sitting in my living room and includes: The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid, Woman World by Aminder Dhaliwal (I have been excited for this for a while!), Black Wings Beating by Alexander London, Tell Me Everything by Sarah Enni, and How to Write an Autobiographical Novel by Alexander Chee. Oh! And Ignite the Stars by Maura Milan (if my library would bump me to the front of the line, please and thank you!).

The Help Desk: The movie is worse, but the book is longer

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Cienna is off this week; the following column was originally published in 2015.

Dear Cienna,

Has there ever been a movie adaptation that's better than the book it's supposed to be based on?

Douglas, West Seattle

Dear Douglas,

That's like comparing apples to Amtrak. While they've got plenty of flash and money, movies can never hope to encapsulate the depth and imagination of books, let alone best them. The two mediums are as vastly different as a fortune cookie is from my favorite psychic-slash-preschool-teacher, Raven Moonwhisper. Sure, the cookie is momentarily satiating and its simple platitudes vaguely pleasing, but is a cookie ever going to charge me $50/hr to tell me which of my spirit guides is too drunk to trust and whether I should quit my job to pursue a career in animal husbandry? (Through trial and error I have discovered farm animals find my presence unnaturally arousing.)

At best, a good movie can enhance a great book experience in much the same way that playing Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon enhances silent screenings of The Wizard of Oz and Schindler’s List.

But to answer your question: Ben Hur is definitely more entertaining than the Bible.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Richard Hugo

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Saturday, September 22: Hugo House Reopens

This Saturday, Hugo House is reopening its doors, on the ground floor of a big fancy new building Starting at 5 pm and running until late, the House will be hosting a sprawling, free-form literary party to introduce the new halls and classrooms and event spaces to Seattle.

Alongside special guests like Maria Semple and host Nancy Guppy, the House will be home to a freewheeling collection of local talent. The Vis-à-Vis Society and the Bushwick Book Club will be unhand to interpret the moment in art. Readers Anastacia-Renee, Quenton Baker, Kristen Millares Young, and Amber Flame will be giving special "pop-up" performances. And there will be an open mic, giving everyone the opportunity to baptize the new Hugo House stage with their own literary artistry.

Hugo House, 1634 Eleventh Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org., 7 pm, free.

Golden Heartbroken

It’s been a busy time in the realm of genre-specific literature awards. First, the World Fantasy Award stopped modeling the design of their trophy on the face of noted author and racist H. P. Lovecraft.

Next, the name of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal was changed to the Children’s Literature Legacy Award, distancing it from some virulently bigoted passages in Wilder’s books. And now, the board of the Romance Writers of America have announced that 2019 will be the last year for the Golden Heart, the contest for unpublished writers that RWA has run for nearly forty years.

The first two are explicit responses to a canonical figure’s open racism. The third, though, involves the more insidious kind of prejudice that works in the shadows, under the cover of anonymity and institutional process.

All three changes have sparked reactionary backlash: some people see the change as a necessary fix, and others see it as an upheaval and buckle down in defense of tradition. It’s one small facet of the great crisis of our present age: how do we instill empathy? How do we convince people to care about interests other than their own? How do we get a lot of white people to help dismantle a system whose operation is both beneficial to them personally and invisible to those it most benefits?

The Golden Heart’s end is not explicitly about racism. There’s no one Great Name acting as a tarnished lightning rod for critique. But among RWA members, both published and not, the debate surrounding the award’s elimination involves detailed arguments about resources, especially time and money — and race in America is a category we often use to evaluate how well both of those are spent. Mortgage lending, for instance, is filtered through this lens constantly; this is how we ended up with redlining, a major framework by which wealth was siphoned out of black populations and reinvested in white neighborhoods. To see how something similar is at work in the Golden Heart, look at the structure: how the contest is run, what it offers, and who it leaves out.

RWA is a powerful writers’ organization in no small part because it is big — 7,306 general members by this year’s count — and it’s gotten this size largely by being inviting. Unlike the Mystery Writers of America or the Science Fiction Writers of America, RWA allows unpublished writers to be full voting members. Anyone can join as long as they can pony up the annual dues and have a romance manuscript in progress. The manuscript requirement (20,000 words of romance in any subgenre) is fairly new, and when it was added many in RWA worried it was too high a bar, both to new arrivals and to longtime hopefuls who hadn’t produced work in a while. Adding obstacles to a new writer’s path seemed to undermine the organization’s entire purpose.

More crucial ways RWA fails to be inclusive have come under scrutiny in the last two years. In 2017, right as Hurricane Harvey was bearing down on RWA headquarters in Houston, bestselling author Linda Howard unleashed a parallel social media storm in the forums of RWA’s Published Author Network (solid context and summary here). Howard claimed the current RWA board was focusing too much of their attention and budget on what she described as “social issues” and that efforts to better include marginalized writers were a form of reverse discrimination. In the resulting flurry of posts, she and her supporters argued that focusing on minority groups was unfairly diverting time and money from the white, straight authors who make up the bulk of RWA membership; opponents countered that other demographics have been long shut out and shouted down, and that correcting this dynamic was both an ethical duty and crucial to RWA’s future.

Just over a year later, the RWA Board announced that they were reevaluating the Golden Heart, in no small part because it benefits only a fraction of the membership. According to the official RWA blog, only a very small 5% of members enter the contest, and only 40–45 individual writers are named finalists. The post also said the contest costs twice as much to run as it brings in.

On July 18, smack dab in the middle of the national conference – and just before the Annual General Meeting – RWA posted highlights from the quarterly board meeting that presented the Golden Heart’s elimination as an established fact. Comments bubbled up as the news spread, and writers stepped up to the mic at the meeting to weigh in. One defender started to ask how the board could justify spending money on one minority group (marginalized authors) but not another (Golden Heart entrants), but her time ran out before she could complete the question – or before the board was forced to explain that “Golden Heart hopeful” was in no way a legally protected class.

The Golden Heart might only benefit a few, but its advantages are many: finalists from all the contest’s history have cited the vast amount of emotional support, expert advice, and industry access they’ve received as a result of entering. For decades a finalist placement in the Golden Heart was one of the most direct ways of getting your manuscript seen by an agent or an editor at a publishing house. Digital books and self-publishing have made it easier for new, gifted writers to find markets outside traditional publishing paths, but a wider, wilder map needs more training to navigate than a set of fixed directions. Networks become indispensable.

This is where the Golden Heart confers a real advantage. In the months before each category’s winner is announced, every year’s class of finalists picks a collective name; these names crop up for years afterward in group blogs, in book dedications, and in nearly every thank-you speech at the award ceremony. One of the strongest statements in the Golden Heart’s defense this year came from the collective blog of the Ruby Slippered Sisterhood, the name chosen by the winners/finalists from 2009. Elisa Beatty writes: “[the] Golden Heart is an important means for identifying some of the strongest new talent. And then making sure they’re getting the support they need.” In an industry where sea changes happen daily, the Golden Heart provides an anchor: a deadline to aim for, a visible achievement, a link with writers past, present, and future. 2018 finalist Eileen Emerson says that stability trickles down:

We all share what we’re learning with our chaptermates, with our critique partners. So, yes, just 45 people each year get the little gold pin and the ceremony and the chance to be up on stage, but the benefits keep rippling out to our personal networks.

Which is another way of saying that finaling in the Golden Heart is a good way to become a gatekeeper — of information, of industry access, of status. Past winner and emcee of this year’s award ceremony Pintip Dunn put it even more clearly: “Finaling in this contest is the true prize.”

She’s right — because the biggest reward of the contest is offered to finalists as well as winners. I’ve been an active RWA member for ten years, but it’s only this year that I learned about the Golden Network, the only chapter in all of RWA with a membership qualification: only Golden Heart finalists and winners are allowed to join. Not only do finalists have the support of their fellow Golden Heart classmates as they start the next phase of their careers, they also are inducted into a company full of high-scoring authors from years past, many of whom have become notable names on bestseller lists and conference programming. They are able to draw deeply on others’ experiences and knowledge as they move to the next phase of their careers.

In theory, this kind of mentoring is precisely what individual chapters are designed to do for new writers. In practice, big-name authors tend to fade away from participating in local chapters as their own careers demand more of their time. And if you’re adding up to 40–45 new members every year — less the ones who final in multiple years, which definitely happens — then that’s a much larger annual increase than most chapters ever see. With all the talk about sisterhood that surrounds the Golden Heart, it’s very hard not to see the Golden Network as a romance author sorority or gated community, a bright golden line drawn between insiders and outsiders.

So the question becomes: how hard is it to final in the Golden Heart? How many hurdles stand between any one author and this wealth of information and connection? The general answer is: nobody really knows. The judges are anonymous, the scoring system is vague and wildly subjective, and there is no feedback offered to contestants who do not make the list. You are either in or you’re out, and you can’t even ask why.

The more complete answer is: it’s much, much harder to final if you’re writing marginalized heroes and heroines. Author Nicki Salcedo wrote frankly about entering her manuscript with a black heroine in 2011 and scoring in the bottom 25%; the next year, she removed all references to the character’s race, and the exact same book was named a finalist. Compare this to Scarlett Peckham’s experience after her book reached the shortlist in 2017. She didn’t win that year but she did join the Golden Network, and the next year’s list of finalists in the historical category included three of her manuscripts, one of which went on to win. That book (The Duke I Tempted, reviewed in August’s Kissing Books column on this site) went up for sale a scant two weeks after the award ceremony, published by an agent Peckham signed with two months after her triple final. She went from “aspiring writer” to “award-winning published author” in the space of a single year.

Meanwhile, Nicki Salcedo’s manuscript was sent for final-round judging to an editor from a major publisher who said, bluntly and with appalling cruelty: “I hated it.” Salcedo writes about how this painful experience stalled her fiction writing for years afterward, and that she’s only recently started up again. For her, the Golden Heart was not a springboard, but a trap door. It’s an all-too-familiar story for authors of color, who face more than the usual amount of rejection in the wall-to-wall whiteness of publishing.

Two authors’ experiences may not constitute a full data set — but one of the big problems here is that there is no data set. RWA only started recently began collecting data on the demographics of the Golden Heart entrants and judges. We are left to guess at the value of the contest based only on rumor and reported experience. And when judges are anonymous and the process obscure, even one racist judge in the judging pool becomes a problem for every potential entrant. You cannot remove biased judges if you cannot first identify who the biased judges are.

You also cannot talk about the Golden Heart without talking about the RITA Awards, RWA’s much better-known contest for published authors. The RITA shares a lot of process and therefore a lot of problems with the Golden Heart. The judging criteria are virtually identical in language, for one thing. Past years have been infamous for the appearance of Nazi heroes and various other flavors of problematic on finalist lists. And here’s a real kick to the gut: no black author has ever won a RITA — even though black writers have been publishing and popular since before RWA existed and during every year the RITAs have been held. This year there were no black authors on the shortlist for the RITAs in any category, even though some of the year’s most popular and critically acclaimed romances were written by black women.

Some have argued plaintively that you can’t have black finalists if you don’t have black authors entering the contest; unlike, say, the Hugos, which run on reader and fan nominations, RITA hopefuls must submit their books personally, or have a publisher submit on their behalf. This argument identifies a pipeline problem but doesn’t address the question of why black authors especially have come to consider the RITAs a waste of their valuable time and effort. It is not that black romance writers do not know about the RITAs: it’s that they know the RITAs all too well.

When this year’s RITA finalists were announced, some outraged, well-intentioned members offered to pay next year’s contest fees for POC writers. But black writers aren’t staying away in such numbers because of contest costs. Black writers are staying away because some RWA members view them as less than human and judge their books by this twisted standard. Many authors of color have reported suspiciously low scores from one or two judges on a book that otherwise scores highly, alongside editor and agent feedback that describes a book as “not relatable,” among other coded terms. RWA has made recent changes to the RITAs to allow future entrants to appeal if they feel a judge has been discriminatory, but it’s very much an open question whether this will be enough to repair the trust that has been lost.

It is easier to critique the RITA finalist lists, because the books there are published and public and we can have a conversation on the relative merits of the texts. There is some sunlight there to illuminate the broken places. But the manuscripts in the Golden Heart are unpublished and therefore a mystery (Scarlett Peckham being a unique and very recent exception). They may well be picked up by editors and agents, or self-published — but they will certainly be revised and edited, the titles will change, authors will get new pen names, and it may be years before the book is introduced to the reading public.

This means that when we talk about the Golden Heart, we have to talk about the authors, because there is no way for us to talk about the content of the books. And what we see is that marginalized authors are actively thwarted at various points: racist judging filters out some in the initial round, then industry bias gets a few more, then authors begin self-selecting out of a harmful process, and all those contest resources and benefits end up being focused on white authors who write about white characters – and who in turn support other white authors in following years. The exclusion is self-reinforcing.

I’m not saying the Golden Heart is intrinsically racist — no more than any other literary award. What I am saying is that in an organization that has real, long-standing problems with inclusion and where some unknown percentage of members see this as a feature, any tools for advancement are going to be leveraged in racist ways. Writers who fit these biased criteria are going to gain more and more advantages, and writers who already have to struggle against systemic prejudice are forced to struggle even more.

The problem is not just structural: the problem is the attitudes some members are bringing into the structure. The fact that they can do this in silence and secrecy makes it all the more insidious. The changes to the World Fantasy Award and the Children’s Literature Legacy Medal were both about taking away visible icons of racism; the problem RWA struggles with in its contests is racism’s invidious, invisible mechanisms.

Eliminating the Golden Heart solves the problem of racist judges by eliminating all judges in one fell swoop. That space and its newly freed-up resources hopefully can become a home for something new and exciting and potentially valuable for everyone. But all those problematic, anonymous judges are still waiting in the wings (and still judging the RITAs). Whatever replaces the Golden Heart needs to keep in mind the presence of bad actors in the membership. Clarity, transparency, and accountability of the process are good places to start.

The time for defending this tradition has passed. It’s time to build something better for our future.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Quick, to the Bat-pole!

All anyone on the internet can talk about right now is an impossibly famous, wealthy, and powerful man's penis. The revelation has inspired crude jokes, boundless speculation, and more than a little controversy.

I'm talking, of course, about Batman.

The first issue of the three-part Batman: Damned series was published yesterday, and for several panels in which Bruce Wayne wanders around the Batcave nude, artist Lee Bermejo clearly illustrated the contours of Wayne's penis. Before you start worrying about the children, you should know that this comic is intended for adult audiences. Damned is the first original series to be published by DC Black Label, a new imprint allowing for idiosyncratic takes on classic DC Comics superhero characters.

The fan response to Batman's wang was so loud and so unhinged that DC Comics apparently edited the offending unit out of the digital version of the comic. This means that DC could perform the same edit job on future editions of the comic, so the copies of Damned that are on the shelves right now might be the only chance readers will ever get to see Batman's genitalia in an official DC Comic. For whatever that's worth.

Damned is a horror story in which Batman may have killed The Joker. (Our hero, having suffered a traumatic injury on the night that the Joker's body was found, doesn't remember what happened.) All sorts of DC Comics dark fantasy characters show up including John Constantine, the Enchantress, Zatanna, and a personal favorite of mine — Deadman. It's pulpy fun that feels reminiscent of those early days of Vertigo, when Superman would wander into a Sandman comic and try to grit his teeth and ignore all the weird shit happening around him.

The big selling point here is Bermejo's painted art, which portrays Batman as a giant slab of beefy eroticism. It's like what would happen if Tom of Finland illustrated the comic adaptation of a Batman movie. Brian Azzarello's script establishes a large cast of characters and a good central mystery, although there's way too much narration on just about every page. Bermejo can relay more information in a single panel than a hundred captions. ("He's running for his life," reads a single caption in a panel depicting Batman running for his life.)

The most exciting part of Damned, for me, has nothing to do with Batman's penis. It's the format of the book. Damned is presented as a graphic album: for $6.99, it's bigger and wider than the average comic, it's printed on better paper, and it's squarebound. It's a format that demands the reader take the art seriously, and Bermejo makes the most out of the high-definition treatment.

Despite Damned's early in-comic tributes to classic Batman tales The Killing Joke and The Dark Knight Returns, I don't think it will take a place alongside those books as an all-time great Batman story. Explaining Deadman — a circus performer who died and is now spending his afterlife hunting down his own murderer by possessing innocent bystanders — to a general audience seems like too much of a lift. But for hardcore readers who like to see different interpretations of their favorite heroes, Damned is an interesting, uh, package.

Librarians in the small town of Rumford, Maine, put up a display of banned books. A group of local pastors got together and tried to ban the books in the display.

Revisiting "Reset"

Published September 19, 2018, at 12:00pm

Since Ellen Pao published Reset, everything's changed for women in tech. Right?

Meet the new Hugo House

Hugo House Executive Director Tree Swenson welcomes donors to the still-in-progress Lapis Theater on Monday evening.

The best part of the new Hugo House space on Capitol Hill, according to Executive Director Tree Swenson, is the way that architecture firm NBBJ bedecked the space with "just little details everywhere."

For the last couple of years, Swenson has been tightly wound as she's shepherded the Hugo House from its old space into an interim location on First Hill and then back to its new incarnation. Now, she's almost made it: the House is just a few thousand dollars shy of owning the new home outright (albeit at far below market rate.) That means donors won't have to worry about being continually tapped and re-tapped in order to pay off late rent; the space — after a capital campaign raising 7.5 million dollars — will be entirely bought and paid for.

If you feared that Hugo House's new space would be boxy or bland, you can officially relax: walking around the House is anything but boring. All the classrooms are different sizes, each room has at least one little secret embedded into its construction, and the interior of the space allows for a ton of natural light to seep inside.

The bar is right there at the entrance, welcoming in writers and readers with graffitied wood from the House's raucous last days in its old location. Around the corner, you'll find some nice, private booths and a tiny pocket stage with a little stairway to nowhere for more people to sit.

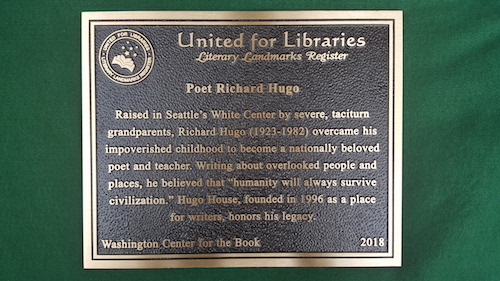

Arguably the crown jewel of the new space is the Lapis Theater, an immense reading area that can seat roughly 150 people. The theater is so named, Swenson says, because Seattle arts megadonor James Ray "was very interested in all things Egypt, and it's named after his favorite stone." (The giant neon art deco "Lapis Theater" sign from Western neon wasn't quite finished in time for Hugo House's opening night party, but soon it will be installed over the entrance to the space.) The room is large and high-ceilinged, and it can be sectioned off into smaller areas with a series of soundproof curtains. On Monday at a special donor event, the Hugo House announced that the House was installing a plaque identifying its unique status. "We are the first Literary Landmark in Washington state," Swenson announced. The Literary Landmark program recognizes significant contributions to American literature: a Nebraska prairie representing the life and work of Willa Cather, for instance, or the Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden in Massachusetts. This particular plaque, which was sponsored by the Washington Center for the Book, recognizes Richard Hugo. The body reads:

Raised in Seattle's White Center by severe, taciturn grandparents, Richard Hugo (1923-1982) overcame his impoverished childhood to become a nationally beloved poet and teacher. Writing about overlooked people and places, he believed that "humanity will always survive civilization." Hugo House, founded in 1996 as a place for writers, honors his legacy.

The new House is awash in Hugo: his quotes are on the walls and ceilings. The hallways and classrooms are named from his work. (Not every space takes a name from Hugo, though; the interior garden area, delightfully, is named Rivendell Garden and is dedicated with a quote from Tolkien.)

You'll have your first opportunity to visit the new Hugo House this Saturday night from 5 pm until late. Swenson hopes that you will agree that space "reflects a writerly individuality." She encourages writers and readers to "dig into these funny corners" of the space, to see what they'll find.

Certain curmudgeons will never be happy with anything but the old Hugo House space, and those people are destined to be unhappy. But for everyone else, there's a lot to love about the bustling new Hugo House. If you enter with an open mind, you'll likely find a corner inside that feels like it was made just for you.

Mail Call for September 18, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

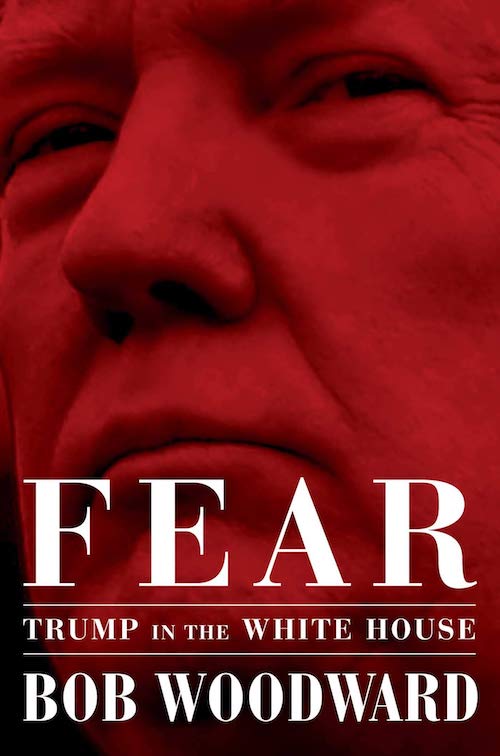

Fear itself

By now, you've read all the salacious excerpts from Bob Woodward's new book Fear: Trump in the White House. Maybe you've found a few of the quotes to be mildly alarming, but I suspect you're not really surprised by anything you've read. Woodward isn't telling us anything new in Fear — we've read about Trump's ineptitude and mediocrity and outright juvenile behavior in the New York Times and in Fire and Fury and in a dozen other places. But none of those other sources carry the same kind of authority as Woodward, who has become the contemporary presidential historian of our time.

What Woodward is providing in Fear, then, is a first draft of history, a record that historians will corroborate or criticize for decades to come. It's an important role, and one that Woodward seems to relish. But you can't really turn to Woodward for good writing — it's remarkable to me that after five decades on the job, he still can't seem to determine the difference between a good sentence and a bad one. And Woodward is primarily interested in the temperament of an administration and the way the primary players interact within the closed system of the White House, not in the results of an administration's policies and its effects on the world.

So Fear reads in some ways like a drawing-room drama, a compact little play with an unbelievable cast of characters, all committing unrealistic actions and saying unintelligent statements to each other. It's easy to forget, in the world as Woodward portrays it, that children are separated from their parents and suffering in camps right now. The book provides very little evidence of the regulatory disasters the Trump administration will cause. Woodward doesn't devote too much time to the enormous payout to the wealthiest Americans that Trump fought for in his first year, instead chronicling the ups and downs of the passage of the tax cuts.

Woodward's Washington is a place where politics is a game of points, with winners and losers, and those results are determined through conventional wisdom. Woodward is interested in which pundits appear on the Sunday morning shows and what they say about his book. He's less interested in the impact these people have on everyday Americans. It's political writing for the sake of politics, not for the sake of the nation.

At this point, I can't make a compelling case why anyone should read these firsthand accounts of day-to-day life in the White House. Does it matter if we know that Trump often doesn't shut off the TV and go to work until 11 am? Do we need another account of Trump lying directly to an aide's face when both men know what the truth is? Why do the specifics matter? Isn't it better to stay focused on the things we can affect in the world, rather than the details of people who don't know our names and don't especially care if we live or die? Why read Fear when it will do nothing to soothe the real fear we feel every day when we wake up and remember who's in charge of the country?

Book News Roundup: Booing Crumb

An all-star team including Macklemore and Garfield High educator and activist Jesse Hagopian has come together to make sure copies of Teaching for Black Lives — “a handbook for creating the sweeping reform of our education system and equitable teaching strategies for Black students”– are in every middle and high school in the Seattle Public School system.

Capitol Hill bookstore Ada's Technical Books is expanding into a pop-up shop in an AT&T store on Broadway. The new space, called Ada's Discovery Cafe, will have some books but will mostly be centered around coffee. To learn more, Capitol Hill Seattle Blog (them again!) describes the new space.

Rob Owen interviewed Seattle writer Lindy West about her upcoming TV show Shrill.

The Queen Anne Book Company has a new neighboring coffee shop, the Queen Anne Coffee Company. In a Facebook statement, QABC assures its followers that just because the names are similar, there's no relation between the businesses. QABC's former neighbor, the beloved El Diablo Coffee, recently had to move their business after some drama. I have not been to Queen Anne Coffee Company, but I can tell you that El Diablo's Cuban coffee is one of the best cups of coffee you can get in this city.

At a small press comics expo over the weekend, two mentions of cartoonist Robert Crumb were met with boos. Crumb, who was not in attendance, is facing new scrutiny in the #MeToo era. Virtually all of Crumb's cartoons demonstrate examples of racism and misogyny that have not aged well, and now the old guard of cartoonists is lecturing the younger generation on Crumb's importance and the kids aren't having it. K. Thor Jensen provides an overview of the situation on Medium.

I know, I know: listicles are bullshit and the idea of a "canon" is bullshit. But any canon that places Helen DeWitt's excellent The Last Samurai at the top is a canon that I can appreciate.

Apple has finally revamped their ugly and awkward ebooks app.

Intent to Vacate

To the feminist karate union and the screeching

motorcycles on 1st Ave, burnouts a block long.

To the skater punk snapping selfies in the sun,

wearing a scruffed up t-shirt the same shitty

black as oblivion, not smiling, not even the eyes.

And also to the tangueras who drown oblivion

with their bodies, a terrible drone of beauty.

To the morning yogis I love to hate in their spandex

and grace making asanas before light. To impossible,

delicate hijabs framing the face of six-year olds

who skip in to an old brick school. To the kids,

the mother buying frijoles y tortillas for dinner again,

invisible men building and feeding and cleaning

the city to send dollars into walls of casas

they’ll never know. To the inherited, lucky wrench

in the mechanic’s hand, to the boozy cherry

on a toothpick, to the fruit trees no one picks clean,

the cherries and plums and apples. The blackberries

rotting on city brambles. To the spoiled kids, the quiet

kids and the angry kids and the yes kids and the no

kids, to all the kids who haven’t yet met oblivion

but are learning the ways to shape themselves

around it. To the techies who never really know

what to do with their money. And the few who do.

To the bus drivers. To the crackheads, the fishermen

weaving their nets and blackstacking North.

To the woman and her cart on the canal not leaving,

staying, how many days, under a broken umbrella?

To sail boats, to craft ales on sale, to jackhammers,

to cranes. To Seattle, you ache too hard, vibrate

at the seams. Like flint. Like caught breath.

Like NW’s finest weed burning a hole in the throat.

Once the moon was the minute hand, the seasons

the hour. What I miss most is stillness.

Neil Gaiman and David Sedaris back to back, Nov. 18 and 19

Returning sponsor Northwest Associated Arts is here this week to make sure you have a chance to reserve seats before they're gone — both are more than half sold out already. Gaiman is almost universally beloved, and his scope is huge, so he draws readers from across genres. Sedaris is a Seattle favorite, and he returns regularly to test new material against our, ahem, discerning ears.

Get more information on our sponsor feature page, then buy tickets for both. It's a rare chance to be surprised and delighted, in two completely different ways, two nights in a row.

Sponsors like Northwest Associated Arts make the Seattle Review of Books possible. We're almost sold out through 2018 — there are only three slots remaining! The fall sold out incredibly fast, so grab this chance to get your stories, or novel, or event in front of our passionate audience. Take a glance at our sponsorship information page for dates and details.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from September 17th - September 23rd

Monday, September 17: Washington Black Reading

Canadian author Esi Edugyan's unlikely novel about slavery and adventure was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Tonight, Seattle audiences get to hear the book in the author's own words. She doesn't make it out this way often, so go see her now. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, September 18: Sikh Captain America

You've probably seen Vishavjit Singh in Seattle media over the last few months. Signh, who dresses in a modified Captain America costume, uses cartoons and comics to fight racism and intolerance. His exhibit "WHAM! BAM! POW! Cartoons, Turbans & Confronting Hate" is currently on exhibit at the Wing Luke Museum. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 6 pm, free.Wednesday, September 19: WordsWest Literary Series

Seattle fiction writer Greg November possesses the kind of resume that authors used to have: he worked as a "house painter, truck driver, forklift driver, knife salesman, generator salesman, executive assistant to the general manager of a luxury hotel in Santa Barbara, and fulfillment coordinator in a chemical history museum." He'll be joined by poet Joannie Strangeland for this installment of West Seattle's best reading series. C&P Coffee Co., 5612 California Ave SW, http://wordswestliterary.weebly.com, 7 pm, free.

Thursday, September 20: A Heart In a Body in the World Reading

Seattle author Deb Caletti's new novel is about a young woman who runs from Seattle to the other Washington — Washington DC. The book is about grief and overcoming pain and trauma. University Book Store, 4326 University Way N.E., 634-3400, http://www2.bookstore.washington.edu/, 7 pm, free.Friday, September 21: The Sarrocco Siblings

Former Seattle author Nicole Sarrocco is the author of a great poetry collection titled Karate Bride. She is now two volumes into a memoir. The first memoir is titled Lit By Lightning and the second is titled Ill-Mannered Ghosts. Tonight, she's joined by her brother, who frequently reads in Seattle. Arundel Books, 212 1st Ave S, https://www.arundelbooks.com/, 6 pm, free.Saturday, September 22: Hugo House Grand Re-Opening

See our Literary Event of the Week column for more details. Hugo House, 1634 Eleventh Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org., 7 pm, free.Sunday, September 23: Kindred Comic Reading

It takes a lot of guts to adapt one of Octavia Butler's most beloved novels into comic form. Tonight, artist John Jennings and writer Damian Duffy will read from their adaptation of Kindred, which has been reviewed surprisingly well. If you've ever wondered how comics artists adapt literature into comics, this is your best opportunity to ask someone who's done it. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.

Literary Event of the Week: The Hugo House reopens with a huge party

It seems like forever ago that the original location of the Hugo House closed its doors with a raucous party in which people wrote all over the walls of the neighborhood writing center. (It was actually just two years, but two years in Trump-adjusted terms is the equivalent of six lifetimes.) People wept, got sloppy drunk, and swore up and down that Seattle would never be the same.

This Saturday, Hugo House is reopening its doors, on the ground floor of a big fancy new building. And sure, those folks who argued that the House would never be the same are technically correct. The old Hugo House, the one that was a funeral home, literally doesn't exist.

But the new Hugo House space contains pieces of the old House — and I mean that as literally as I possibly can; old House artifacts have been reshaped into the new space. And there are plenty of flourishes for writers to love in the new House. (We'll be sharing our walkthrough of the new space a little later on this week, where we'll talk about all that in detail.)

But you don't care about the why and the how of it. You care about the celebration. Starting at 5 pm and running until late, the House will be hosting a sprawling, free-form literary party to introduce the new halls and classrooms and event spaces to Seattle.

Alongside special guests like Maria Semple and host Nancy Guppy, the House will be home to a freewheeling collection of local talent. The Vis-à-Vis Society and the Bushwick Book Club will be unhand to interpret the moment in art. Readers Anastacia-Renee, Quenton Baker, Kristen Millares Young, and Amber Flame will be giving special "pop-up" performances. And there will be an open mic, giving everyone the opportunity to baptize the new Hugo House stage with their own literary artistry.

After the party, DJ Gabriel Teodros will be spinning records for a literary dance party. I expect that people will get drunk, and there will be plenty of surprises and reunions and, yes, messy drama. But please do me a favor and don't write on the walls or break anything, okay? This place has to last a while.

Hugo House, 1634 Eleventh Avenue, 322-7030, http://hugohouse.org., 7 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for September 16, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that’s your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Tensions in Seattle Somali Communities Lead to Author’s Cancellation

Call Me American, Abdi Nor Iftin’s just-published memoir about his experiences as a child during the civil war in Somalia and his long journey to the United States, should have been a feel-good story. As Rich Smith reports, the book’s own journey has been one of conflict rather than celebration, with events cancelled first in Portland, Maine (where Iftin lives) and now at Seattle’s Town Hall. A surprisingly complicated story about representation, community pride, and the very different sensitivities of the literary and development sectors.

In an e-mail, a spokesperson for Town Hall says they canceled because the organizations they'd partnered with for the event pulled out, including "a notable Somali organization" that didn't want to participate "in something they see as dividing their community."

Town Hall had hoped to "facilitate a conversation in partnership with Forterra [a conservation organization] and representatives of the local Somali community," according to their spokesperson. But Forterra, who had served as the liaison between local Somali communities, pulled out after receiving complaints about Nor Iftin.

Why Did the New York Review of Books Publish That Jian Ghomeshi Essay?

Meanwhile, in the same week that Harper's published a self-serving account of social and professional ostracization by John Hockenberry, the New York Review of Books has an issue about #MeToo devoted entirely to men, including a defense of Jian Ghomeshi by ... Jian Ghomeshi. Slate's Isaac Chotioner asked editor Ian Buruma why.

Was there a gender breakdown during the discussion?

I would say not necessarily just in this particular case. I would say that on issues to do with #MeToo and relations between men and women and so on, there isn’t so much a gender breakdown as there is a generational one. I think that is generally true. I don’t think our office is in any way unusual. I think people over 40 and under 40 often have disagreements about this.

How old are you?

I’m 66.

To Restore Civil Society, Start With the Library

Recently the Ballard branch of the Seattle Public Library installed bars across the concrete blocks outside its doors that are meant to deter homeless people from sitting, sleeping, or otherwise taking refuge near the building. As Seattle’s homeless population grows, the city’s library system has struggled to define how service to this and other marginalized groups fits into its mission — especially how to balance it against service to other stakeholders.

Finding that balance, though hard, could be critical to the survival of libraries as an institution. As sociologist Eric Klinenberg tracks in this essay, the value libraries provide as a civic commons is much harder to duplicate than their most familiar service (access to books and other media). A library that protects its most privileged patrons at the cost of others is less valuable — and more at risk.

As recipients of public funding, Seattle’s libraries are vulnerable to public opinion. Given a choice between supporting our libraries’ ability to serve the broadest possible range of citizens — or putting them in the crossfire of one of our most virulent debates about public policy — what will we choose?

The openness and diversity that flourish in neighborhood libraries were once a hallmark of urban culture. But that has changed. Though American cities are growing more ethnically, racially and culturally diverse, they too often remain divided and unequal, with some neighborhoods cutting themselves off from difference — sometimes intentionally, sometimes just by dint of rising costs — particularly when it comes to race and social class.

Libraries are the kinds of places where people with different backgrounds, passions and interests can take part in a living democratic culture. They are the kinds of places where the public, private and philanthropic sectors can work together to reach for something higher than the bottom line.

Pa. prison books and mail policies draw protests, petitions, and possible legal challenges

Here’s another from the “yes, this is really hard, but seriously” pool: in Philadelphia, people have been smuggling drugs and other contraband into prisons inside of books, so the prisons are barring book donations to prisoners.

The Department of Corrections isn’t trying to ban books. They’re just trying to limit how prisoners lay hands on them — through channels that the prison controls. As a byproduct, prisoners may no longer have access to free books, instead paying for them from wages of less than a dollar per hour.

Critics see the DOC rules as part of the same "war on books" — and they are hoping to achieve the same reversal here. To that end, they’ve already set up online petitions and planned a day of action for Friday to flood state officials and lawmakers with phone calls. Organizations including the Pennsylvania ACLU and the Pittsburgh-based Abolitionist Law Center that have sued the DOC successfully in the past said they are evaluating the situation.

"We’re already starting to get a lot of complaints," said the Abolitionist Law Center’s Bret Grote. "It was only a few days into this in which it became clear to me that this is almost certainly going to result in years of protracted litigation, and it’s going to become a defining moment in the future of prisons in this state."