Too Many Great Readings Tonight!

As we've mentioned, tonight is the very last Cheap Wine & Poetry event at the Hugo House. This is our pick for the best event of the evening; CW&P is a consistently great event, and this is its last time on the Hugo House stage before the House is demolished later this year. Further, the future of CW&P — and the answer to the question of whether CW&P even has a future — has not yet been announced. It's a milestone!

But I wanted to tell you about two other great events happening tonight, because it is an unusually jam-packed Thursday night in literary Seattle.

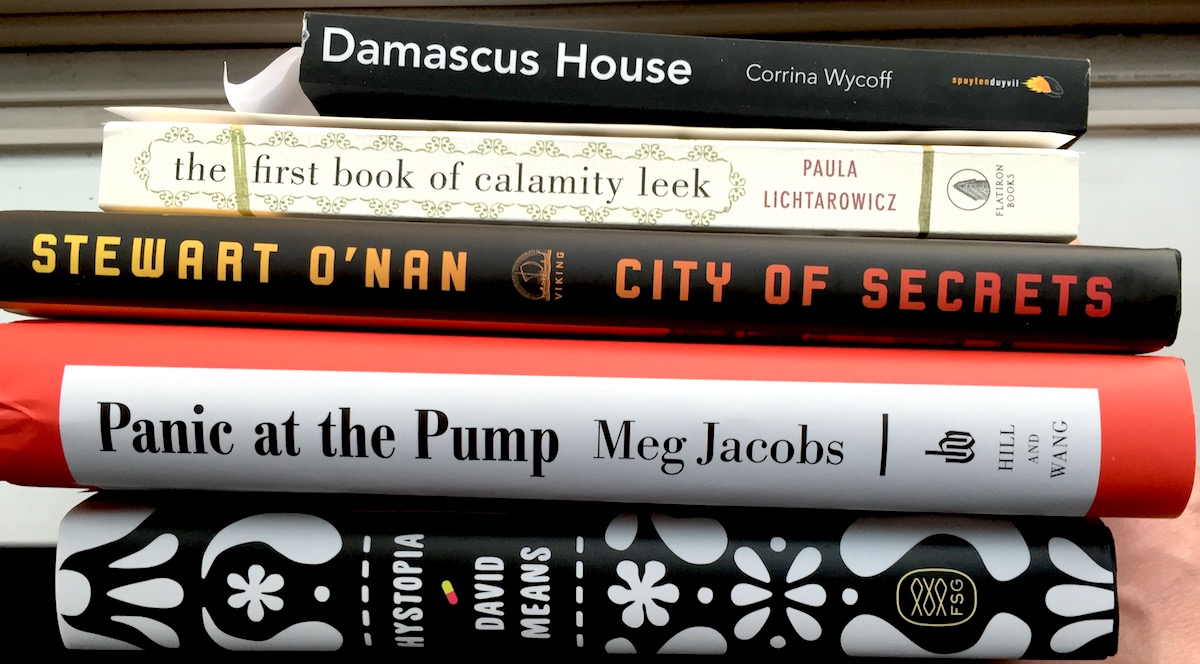

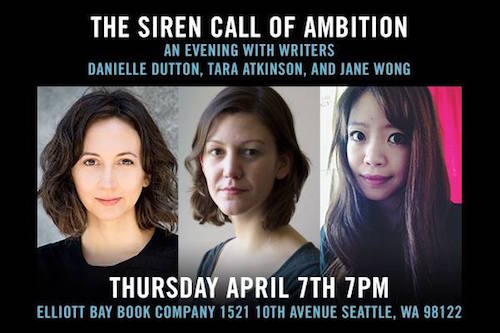

At Elliott Bay Book Company, Danielle Dutton, Tara Atkinson, and Jane Wong will read at 7 pm. Atkinson is a co-founder of the APRIL Festival and she writes excellent short fiction. Wong is one of Seattle's best poets. We've published two of her poems here at the Seattle Review of Books. And Dutton is the publisher of Dorothy, an indpendent press that publishes great women writers. She's also the author of Margaret the First, a novel about a writer in 17th century England, when women were basically not allowed to be writers. This looks like it'll be a spectacular evening.

And at Third Place Books Ravenna, three Seattle poets are reading: Natasha Moni, author of The Cardiologist's Daughter; Erin Malone, author of Hover; and Michael Schmeltzer, author of Elegy/Elk River and Blood Song. (Malone published a great poem titled "Time Capsule" here at the Seattle Review of Books a few months ago.) This is a high-quality lineup of wonderful Seattle poets celebrating National Poetry Month in one of our most charming neighborhood bookstores. What's not to love?

Every week, I go through all the upcoming events to find one literary event per evening to recommend to readers of the Seattle Review of Books. Most nights, I have to decide between at least two cool-looking events. Tonight, there were three. Which one are you going to? Choose wisely.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Everybody's talking about the Black Panther

With all due respect to Stelfreeze, who is one of the best cover artists in superhero comics, those sales are due to the fact that everyone is anxious to see how Coates does with a new medium. Readers expecting a superheroic sequel to Between the World and Me — whatever that would even look like — will be disappointed. Coates has indicated repeatedly that he’s a lifelong fan of Marvel Comics, and that he’s interested in writing a superhero comic.

And so Black Panther is a superhero comic, through and through. It opens with a big fight, packed with laser blasts and super-powers and costumes. It’s dramatic, even operatic, and it’s a lot of fun to read. But even Coates at his nerdiest is still Coates, and his day-job interests are on display here: politics, race, violence, capital punishment. Even the plot seems of-the-moment for a United States whose political structures are hemorrhaging themselves to pieces: the Black Panther is a king of a high-tech African nation called Wakanda, but after years of turmoil his people seem ready for a new ruler.

Like some of the best superhero comics, Black Panther proudly waves the banners of its influences: Kanye West lyrics, tributes to other comics creators, elements of Afrofuturism. Coates is slathering the pop culture on thick, here, and it’s delicious. He's especially gifted at dialogue; the economy of word balloons and captions often escapes writers more used to the vast expanse of prose, but the words on the page in Black Panther strike just the right mix of portentousness, exposition, and brevity. Here’s the Black Panther’s internal monologue from early in the issue:

I came here to praise the heart of my country, the vibranium miners of the Great Mound. For I am their king and I love them as the father loves the child.

But among my children, all I found was hate.

The hate spread.

And so there is war.

You can practically hear the soundtrack ramping up behind those words (Brum-BAUMM!!!!) It reads like Stan Lee-style overblown dialogue, but with more natural poetry to it. The cadence has a majesty, a foreign rhythm, and the condescending tone — thinking of his citizens as children — indicates that perhaps the insurrection has a point to it. Those few words do a lot of work.

And so does Stelfreeze’s art. It’s been years since I’ve seen Stelfreeze do the interior of a book, and I missed his skill at storytelling. Take those first few pages where the Panther faces a crowd of angry Wakandans: every aspect of the melee is laid out plainly. Actions have consequences that we can see, and it’s possible to follow faces in the crowd throughout the fight. Later in the issue, Stelfreeze’s designs for Wakanda incorporate a whole host of visual vocabularies — African art, Egyptian design, weird Jack Kirby technology —to create a corner of the Marvel universe that we’ve never seen before.

In the end, Black Panther has to be one of the strongest first issues from a superhero comic publisher in a long time. It doesn’t feel too slight, or too weighty. It’s a ridiculously stylish package, with production values that put most of Marvel’s other output to shame. And it firmly situates a long-standing Marvel character into his own corner of the world, finally giving him a role and a purpose and a voice after years of disuse. This is what superhero comics should be doing all the time: crafting cultural moments around unique characters who resonate with the politics of the day.

-

It will be interesting to see what new comics readers make of Black Panther. They might not know that you should read the comic over a few times in order to fully appreciate it. The advertisements spread throughout the issue might prove to be too jarring for them. They might consider the years of backstory to be off-putting, rather than intriguing. In fact, a good portion of prospective Black Panther readers should probably wait for the trade paperback to come out this fall, because collected editions tend to be closer to the traditional reading experience than monthly episodic comics. ↩

Book News Roundup: Poet wins Twitter, literature needs diversity, and a self-hating book critic

The debut party for Lesley Hazleton's Agnostic: A Spirited Manifesto last night at Town Hall was a fantastic experience. Hazleton delivered a talk that was part-extemporaneous/part-reading. Hazleton asked the audience to imagine that she held the sun in her hand, that it was about the size of an orange; the Earth, she said, would be a grain of salt circling her hand at 30 feet. The nearest star to our sun would be another orange, approximately in Big Sur. Using examples like that, Hazleton continually deconstructed the audience's sense of scale, to infinity and beyond. The only real sour note of the evening came when two individual atheists took the microphone during Q&A to confront Hazleton about...something. One of the two older white men pronounced himself a "dogmatic atheist." Another said that if God were a person, He'd be thrown in prison for His crimes. (Not an original idea, and not especially relevant to the evening.) Neither had read the book, and neither had any clear points besides being angry about religion. During their tirades, the audience was audibly groaning, but Hazleton handled their non-questions with grace and compassion. By the end of the night, it felt like the rare reading event that perfectly captured the tenor and spirit of the book it was celebrating.

Congratulations to the 2016 Guggenheim Fellowship winners! The list of poets, critics, and novelists who won is very long, but it includes Seattle Review of Books favorites Jenny Offill and Laila Lalami.

At the LA Weekly, Jessica Langlois wonders whether AWP can overcome the lack of diversity in literature:

I was reading Claudia Rankine’s book Citizen: An American Lyric in a hotel bar in downtown Los Angeles Saturday afternoon when I got a series of texts from my partner, who was in Ventura County, sitting by a lake and writing poetry. The police were harassing him. Three white men with guns. He is brown-skinned and has a thick beard. They’d threatened to tase our dog, a rambunctious puppy. “I’m so scared,” he wrote me.

- The Loop Magazine, a magazine published on Apple's doomed "Newsstand" feature, has failed. Remember when the media was led to believe that iPads would save print media? Yeah, not so much.

My struggles are no different from any other developer on the App Store. If you have a game or social media app, you’re golden in Apple’s eyes. Anything else, forget it. (Unless you’re a big publisher, then you’re golden too).

How did poet Patricia Lockwood manage to tweet "fuck me daddy" at Donald Trump from the New Republic's Twitter handle? Well, thereby hangs a tale...

Was Hamlet fan-fiction? Not really, but it is important to note that copyright has absolutely changed the way that writers find inspiration.

Bookslut's editor Jessa Crispin has written a long essay titled "The Self-Hating Book Critic." It's full of bleak thoughts about the future of literature — Crispin has admitted that she's pulling the plug on Bookslut because she's done with modern American literature — but it's also full of some very incisive thoughts about the sorry state of modern book reviewing:

It makes sense to me that when the system goes wobbly, the critical culture responds by saying, “From now on, we will only run positive reviews.” It is a long list of publications and critics who have come out saying this, from The Believer to Buzzfeed to assorted Internet communities. But that of course is not criticism, it is enthusiasm. And enthusiasm only happens in long form when all uncertainties and unknowns have been weeded out. When expectations are met. It is a way to regain control. Uncertainty causes anxiety, and when things are already uncertain due to a literary system in flux, it is easier to close off, to shut the gates, to only admit those whose entrance is guaranteed. To, you know, review your friends.

Give me a G-R-E-E-N-W-O-O-D!

Published April 06, 2016, at 12:00pm

All of Greenwood has come together to make a book about Greenwood to aid in rebuilding Greenwood. Bonnie J. Rough has our look inside.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from April 6th - 12th

Wednesday April 6: Lit Fix

The books-and-booze-and-bands reading series, founded on the revolutionary concept that readings can and should be fun, celebrates its third anniversary with a brand-new home at Chop Suey and a killer lineup: poet Michelle Peñaloza, author Anca Szilagyi, poet Anastacia Tolbert, young adult author Sean Boudoin novelist Gint Aras, and musical act The Wild. Chop Suey, 1325 Madison St, 538-0556, litfixseattle.com $5. 21+. 7 p.m. (Full disclosure: the Seattle Review of Books is a media sponsor of this edition of Lit Fix. No money was exchanged or anything like that; we're just big fans and so we gave them ad space in the Seattle Weekly to promote their reading.)

Thursday April 7: Cheap Wine & Poetry

The long-running series pairing compelling poets with $1 wine will gather one last time on Hugo House’s stage. Readers Roberto Ascalon, Sarah Galvin, Tara Hardy, and—her again!—Michelle Peñaloza will see the series off in style. Will CW&P continue? Will it move with Hugo House or find a new venue? Stay tuned. Hugo House, 1634 11th Ave, 322-7030, hugohouse.org. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Friday April 8: Hometown Heroes

Emerald City Comicon is this weekend, and if you haven’t already gotten tickets, you’re out of luck—the show is completely sold out. But there are a couple satellite events happening that you can attend, even if you don’t have tickets to the big show. First up, on Thursday night at 7 pm, Arcane Comics in Ballard is hosting their second annual All Star Comics party with local cartoonists alongside national comics pros like Jim Mahfood and Alex De Campi. And on Saturday night at 7 pm, Phoenix Comics on Broadway is hosting a party for the popular podcasters behind Jay & Miles X-plain the X-Men.

Even more interesting is Hometown Heroes, a new one-night comics show dedicated to showing off the best cartooning talent Seattle has to offer. Hometown Heroes was inspired in part by complaints from local cartoonists who feel abandoned outside Emerald City’s gates. The minicomics and alt-comics scene in Seattle has for some time now felt marginalized by ECCC’s increasing mass-media vibe, and this year many Seattle cartoonists were unable to even acquire tables at the show. On Facebook, local cartoonists grumble that ECCC has forgotten the local scene that helped make the convention such a big deal to begin with — though it must be noted that it’s not like the city has been locked out of its own convention entirely; Seattle cartoonists like Colleen Frakes and Peter Bagge are featured ECCC guests.

Still, the guest list for Hometown Heroes certainly does look like a who’s who in the Seattle comics underground: James The Stanton, Ben Horak, Katie Wheeler, Marc Palm, Josh Simmons, Noel Frankln, Bagge, Seth Goodkind, Gina Siciliano, and Max Clotfelter are all on the bill. The guest of honor is Stefano Gaudiano, a local inker perhaps best known for his work on The Walking Dead. Hometown Heroes is organized by 80% Studios, the local cartoonists behind the full-color local comics anthology Nemesis Enforcer, a new issue of which will be available at the event. Sponsors for the show include local comics stores Zanadu, Comics Dungeon, Fantagraphics, and Arcane Comics. It’s about as homegrown as it gets.

Hometown Heroes takes place at 1927 Events, an event space about ten minutes’ walk from the Washington State Convention Center. Attendance is free, and everyone who shows up gets a free comic. It’s another testament to Seattle’s cartooning community that our comics convention has become so successful that it needs a supplementary comics show just to showcase all the awesome stuff being created in Seattle right now. This is shaping up to be the hot-ticket Emerald City Comicon afterparty, a more relaxed space where the people who are more serious about comics and less interested in, say, meeting Nathan Fillion in person can gather to talk about the craft, gossip about the personalities, and check out the latest work from Seattle’s alt-comics scene. This is what community looks like.

1927 Events, 1927 3rd Ave, 979-7467, 80percentstudios.tumblr.com. Free. All ages. 6:30 p.m.

Saturday April 9: Encyclopedia Greenwoodia Launch Party

This is a party to celebrate the launch of a book about Greenwood written by students and professional writers (including, full disclosure, me). Come and raise a glass of milk to toast the publication of the book, and the unbreakable spirit of the neighborhood that book celebrates. We'll have more about the book and the party later on today, right here on the Seattle Review of Books.

Greenwood Senior Center, 525 N. 85th St., 297-0875, fearlessideas.org. Free. All ages. 2 p.m.

Alternate Saturday April 9: Mary Roach

All of Mary Roach’s books, about death and space travel and sex and eating, begin with a simple question: what happens next? She’s wildly curious and unashamedly willing to ask the most indelicate questions to track down answers. (Most people would call asking astronauts about their sex lives “rude.” Roach calls it “research.”) Because of this, Roach’s readings are absolute delights; the only thing she loves more than learning is sharing her findings with an audience. Everett Performing Arts Center, 2710 Wetmore Ave., 425-257-0875, Free. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Sunday April 10: The End Is the Beginning and Other Things About Openings

How do you invite a reader into your story without over-setting the table, telegraphing the ending, or otherwise losing the audience? Donna Miscolta—author of the novel When the de la Cruz Family Danced and the upcoming story collection Hola and Goodbye—hosts this free writing class focused intently on beginnings. Seattle Public Library, Beacon Hill Branch, 2821 Beacon Ave. S, 684-4711, spl.org. Free. All ages. 2 p.m.

Monday April 11: Sonny Liew

Singapore-based cartoonist Liew debuts his dazzling new book The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, a meta-biography of an influential elderly Singaporean cartoonist who happens to have never existed. Liew will discuss comics history, Singapore, and more onstage tonight with Seattle Review of Books co-founder Martin McClellan. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, elliottbaybook.com. Free. All ages. 7 p.m.

Alternate Monday April 11: Bard in a Bar: Hamlet

The Seattle Public Library continues their monthlong celebration of Shakespeare’s First Folio with the Bard in a Bar series. Tonight, Hamlet is presented via drunken crowdsourcing. Many of the world’s best ideas — Wikipedia, the Constitution — are a result of drunken crowdsourcing, so this should end well. Solo Bar, 200 Roy St., 213-0800, spl.org. Free. 21+. 8 p.m..

Tuesday April 12: Jacqueline Woodson

Seattle Arts & Lectures lives up to their mission statement of bringing big-name authors to town with Jacqueline Woodson, the National Book Award-winning author of exquisite young adult novels like Brown Girl Dreaming, Beneath a Meth Moon, and Hush. Expect a conversation about the reality in her semi-autobiographical book. Town Hall Seattle, 1119 8th Ave., 652-4255, townhallseattle.org. $15-60. All ages. 7:30 p.m.

Are you there, whoever? It's me, Lesley

Published April 05, 2016, at 2:24pm

Can a whole-hearted atheist find any comfort in Lesley Hazleton's defense of agnosticism?

I am all for the idea of states naming official books. (Make Way for Ducklings is, adorably, Massachusetts's official children's book.) But I'm not a fan of this move:

Tennessee is poised to make history as the first state in the nation to recognize the Holy Bible as its official book.

The problem is, of course, Tennessee lawmakers aren't just naming a state book by doing this; they're effectively naming Christianity the official state religion. Instead of the Bible, a book that I can promise was neither written nor set in Tennessee, why not make Cormac McCarthy's semiautobiographical novel Suttree the state book instead? It's set in Tennessee, and it's an underappreciated McCarthy novel. Why not promote literacy, rather than waging a petty and unnecessary religious war?

Love Letter

It's funny how much we ate —

we couldn't stop.

First dinner, then desert,

then the plates and the table.

At the show, she ate the stage,

I swallowed the microphones.

Back at the room we ate the chairs

the shower and the television.

Naked, breasts poised like the dark mystery

at the center of faith, she devoured the bed —

nothing left.Behind her, arms around her victorious stomach,

I knew what it would take to fill us up.

Nothing short of a falling chunk of sun,

something nuclear come to love us clean,

burn our shadow into the wall just like this.

2015 Floating Bridge Press finalist Maya Jewell Zeller has two poems to share

Sponsor Floating Bridge Press is back to feature a great work from Maya Jewell Zeller, titled Yesterday, the Bees. Zeller's piece was a finalist in the 2015 chapbook competition, a work that looks at parenting, and being a part of a family.

We have two poems from the work on our sponsors page for you to read. Be sure to look, and click through to their website to find out more about Zeller's work, and the other chapbook winners. Thank you, Floating Bridge for your sponsorship!

If you're a small publisher, writer, poet, or foundation that is looking to back our work, and advertise your own in an inexpensive and expressive way, take a look at our open dates. We'd love to talk to you about opportunities to sponsor us. It's our way of making internet advertising something to look forward to.

Notes From the Field - AWP wrap up, the day after

Now that I am home and eating real meals again, there is time to mull over all the cringey moments of AWP 2016. Like when I bum-rushed Kevin Young in order to gush about how much my middle school students loved his poem “Ode to Gumbo.” I actually said, “you’ve got fans in the 8th grade, Kevin.” And then ran away. Or when I stood right behind Rachel Kushner at a small private reception, stared at her hair and, like a super creep, didn’t say anything. Yes, she was wearing leather pants. I think. It was dark and a nervous fan-girl film came over my eyes. Then I ran away for a minute, but the bouncer wouldn’t let me back in. Or when I rushed up to an author I admire and pressed my weird book upon him and said, “bye!” like a three-year-old. I even waved my hand down low in a weird, rapid erasing move, as if I were cute, and small. A toddler would have been charming. I was a weird lady at a conference doing a lot of running.

After spending a few hours shame spiraling and Hoovering cheese puffs, I remembered my haul of books and settled in with Franny Choi’s Floating Brilliant Gone (Write Bloody, 2014). One of the saddest parts of AWP is all the simultaneous events, some of them spread out all over the city, which was made more difficult by LA’s sprawl and car-centric architecture, and the fact that one cannot attend several panels at once. Clearly, I am easily over-stimulated (see above), but, in debriefing with comrades post-AWP, there were many opportunities to kick myself for missing certain events, like Choi’s reading with Danez Smith as part of the Dark Noise Collective. But I have her book, and many more glinting in my stack – memory palaces of my path through the bookfair, where I pinged back and forth all over the place like multiball. John Hankiewicz’s Asthma (poetry dance comics), Nick Courtright’s Let There Be Light (the Genesis creation myth in reverse), Bianca Stone’s Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours, and many more.

I received three lucky amulets this year: a small crystal, a silver Viking homunculus, and a tiny plastic sea anemone. It happened like this: right at the moment I was so tired, or hungry, or feeling so very alone, one of my favorite writer friends (thank you, Corinne Manning, Katie Ogle, Sierra Nelson) would appear and say, “how are you doing?” and palm me this small charm. It reminded me of when I ran a half-marathon, and halfway up this dreadful hill, a woman cheering us on handed me a baggie of gummy bears. The memory of the sweetness and the tiny bumps of bear limbs on my tongue in tandem with her cowbell of a voice can still propel me to huff up that hill. Likewise, I worry these small tokens in my pocket throughout AWP-ing, and stand them next to my head while I sleep to watch over me, miniature guardians, kitchen witches of conference, hoping they will confer on me some of their givers’ wisdom.

I am still mulling over all that went on, remembering Mark Doty explaining how to embrace frustration, discussing the methods he uses to disrupt — changing point of view, tense, syntax, tone, form, even using C.D. Wright’s writing it backwards exercise, to generate surprise. Inspired by a National Geographic photo of a frozen baby mammoth, he found himself struggling to be faithful to history, chafing against “the whole ‘objective’ thing.” He recognized he needed to be faithful to art, and to himself. Kimiko Hahn described it as that moment when she let her character say, “who are you to speak for me?” And here is what Doty’s perfectly preserved ice baby, brought up from the underworld, said:

I am still one month old,

and forty thousand years without

my mother.

I carry this image of aloneness on a scale I can barely fathom – 40,000 years — with me as I move through LAX and home again. How it is to be alone in a crowd of 12,000 like-minded strangers – and the unlikelihood that any of our words will travel that far through time like this baby mammoth, its legs frozen and preserved mid-stride. And how many little things – extremely ancient rocks, warrior miniatures, sea creatures posing as plants, OK! Magazine, minutes waiting in cars – might have something to say if I am listening.

Reflecting on Race and Racism through Poetry, Spoken Word, and Conversation

Editor's note: Donna Miscolta here writes about an exclusive reading she helped organize. In order to attend, you must be an employee of King County. If you are, on April 7th, the program will be welcoming Troy Osaki and Hamda Yusuf for the next in the series of four. The final two: on June 15, the program will have Anis Gisele and Shin Yu Pai, and on September 13 Kiana Davis and Djenaway Se-Gahon. Email her for details if you're eligible and would like to attend.

There are probably not many sentences in which the words poetry and government appear together, but here’s one from the heading of a Washington Post article published last April: “Poetry is going extinct, government data show.”

The article reported that “In 1992, 17 percent of Americans had read a work of poetry at least once in the past year. Twenty years later that number had fallen by more than half, to 6.7 percent.”

First, we might wonder why government is tracking such a thing, to which one might ask rhetorically, “What doesn’t the government track?”

Second, we might wonder, how exactly are they getting such information? It’s called the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, a product of a partnership between the NEA and the United States Census Bureau. Here’s one of the survey’s findings: “According to the latest numbers, poetry is less popular than jazz. It's less popular than dance, and only about half as popular as knitting. The only major arts category with a narrower audience than poetry is opera – not exactly surprising, given the contemporary state of that art.”

Who knew that it was the role of government to offer this observation of doom: “Over the past 20 years, the downward trend is nearly perfectly linear – and doesn't show signs of abating.” The article is full of dire-looking graphs that resemble the bad news spit from an EKG monitor. If poetry is going extinct, then so must be the poets, right?

Over their dead bodies, they’re likely to reply.

Poets will persist. They will survive because they are necessary. They have stories to tell. And as Sherman Alexie says. “I firmly believe in the power of stories to change the world, and I firmly believe in the power of one story to change one life at a time.”

So here’s another sentence in which the words poetry and government appear together: Local poets present their work to King County government employees in a series on race and racism.

I’ve worked in government at the local level for almost thirty years. My job is to plan, design, and oversee projects that create opportunities for residents to conserve resources for a more sustainable future. But what’s a sustainable future without poetry? I’m working on a project with three colleagues to bring poets in to county government offices to read work that reflects their experience in a racialized world. It’s part of the county’s commitment to equity and social justice that must begin with a recognition that racism exists, that it’s been institutionalized in our systems, and that we all have a responsibility to change it. One story at a time is as good a strategy as any.

On January 12, about fifty King County employees assembled in a large conference room in a downtown office building to listen to the poetry of Quenton Baker and Casandra Lopez. It was a new experience for both poets and audience. Baker, upon stepping to the podium, elicited laughter when he remarked that this was the first time he’d come to a government building to read poetry to government employees.

Baker, tall and lanky with an untamed Afro, appears shy and serious. He’s anything but shy when he delivers his poems or banters with the audience or provides context for a piece he’s about to read. He’s straightforward, earnest, and utterly himself, which means he doesn’t alter his language even when in a government conference room full of government employees. If the f word is the right word for the moment and the sentiment, then that’s what glides comfortably off his tongue, whether in his poems or in his speech. And if his poems are serious, dark, and angry, his laughter and smile are quick. Despite never having read poems in a government building, this, nevertheless, is his milieu – a room full of listeners. In this room, the audience was mostly white (and mostly female).

Baker and Lopez took turns at the podium for two rounds of intensely felt and powerfully delivered poems that allowed the audience to see racism through the personal and very vivid lens of poetry.

Baker says his poetry “begins from a place of love and is primarily interested in pushing back against stereotypes, implicit biases, and the myriad ways that various forms of supremacy act on and envelop us all.” Here’s the opening of “Diglossic in the Second America,” which Baker gave us in the cadence of his hip hop roots:

If you're kind, you say high or low. Honest: you say [default] or black.

But we don't say black. Not now. Only dog whistles: welfare queen

tough on crime. Wow! Look at her run, such a natural athlete.

What I mean is: two tongues: high and low speech; white teeth and suit or thug.

But don't I have both? Little mulatto codebreaker, identity that jump cuts like a running back.

Wait, am I even black? How black? On a scale of rapist to corner boy?

Lopez noted the similarities in themes between her work and Baker’s. But there is also similarity in the origin of their work. Most of Lopez’s work explores issues related to loss, identity, diaspora, race, grief, and healing. She says that “though her work tackles difficult subjects, she writes from a place of compassion which allows for multiple points of entry into her work.” Here’s a segment from Lopez’s piece titled “a few notes about public grief.”

don’t look too tattooed. don’t look too uneducated. don’t look too brown or black. don’t look too human, like a person who has made mistakes or has a drink at the end of a long day. don’t look like a person who laughs too loudly with a mouth of joy or someone’s whose body sobs history because that will make you look too brown or too black or too other. remember, you want the judge, officials, and jury to identify with you. don’t give them reason to see you as a thug, gangster or whore. don’t give them a chance to see you as too black or too brown, or too foreign.

When asked by an audience member how they have the courage to write what they do, both poets responded similarly – that it’s not so much a matter of courage, as a need, even an obsession to put their stories on the page. “For black people, survival is such an everyday concern,” Baker said. For both poets, writing seems to be a survival strategy, a way to process for themselves and others their reality in a racialized society.

Lopez, too, despite her poems of tragedy and gun violence, laughs readily, joking between poems. The genuine warmth of her personality suffuses the room, her quickness to laughter perhaps a mechanism to deflect the pain of her words. She gestures often as she reads, a repetitive motion, a slicing with a palm or a pretend pounding of the fist to give stress to her words, or perhaps relieve stress from speaking them.

“I didn’t expect to feel so much,” an audience member said during the discussion following the readings. Someone else, while stressing the value of the event, acknowledged her occasional discomfort.

Did the poets feel any discomfort? Baker replied that if he didn’t feel discomfort then there would be no reason for him to be there.

“What can government do to authentically address inequity?” asked another in the audience.

The artists picked up on and appreciated the word authentically, a clear signal that the questioner was committed to action. Baker said that government has to understand how deep racism is and how much work it takes to break down the power structures that keep out certain segments of the population. Lopez added, “There are people who are doing a lot of this work on their own, but they need a more supportive structure in which to operate.” That seems like an argument for more sentences that combine the words poetry and government.

Because we’re government and we must measure everything we do, we conducted a survey of the audience. Overwhelmingly, respondents indicated the event had increased their understanding about race and racism. And while one commenter worried over the multiple times the phrase “white supremacy” arose, another cheered, “Let’s keep it going – the work is not done yet!” Not by a long shot is it done.

When we asked the poets what could be improved about the program, we got this suggestion: Get more white men in the room. We have three more chances to do that with events in April, June, and September. We’re tracking attendance. Maybe it’ll be a graph in our final report.

Letters to the Editor: Commercialit, revisited

Editor's note: critic Tom LeClair sent this letter to the editor in response to Paul Constant's blog post on LeClair's Daily Beast piece titled "Will Commercialit Ruin Great Fiction?"

In the 40 years I’ve been writing book reviews for national periodicals, it’s rare that one of my reviews is reviewed. In a recent post, Paul Constant called my review of Sweeney’s The Nest in the Daily Beast “unfair.” “Wrong” I could silently accept, but “unfair” seems unfair. Since I assume readers have not committed his piece to memory, I’ll quote from it in italics and respond:

First of all, I don’t care if marketing materials mention the author advance explicitly: there is almost no good reason for a book critic to ever mention an advance in a review.

Generally I’d agree, but I had a good reason. It was not only Sweeney, an unknown writer, who received a million-dollar advance for a first novel. Three other recent first novelists I mentioned received similar advances, which were used to promote their books as new literary discoveries when, in fact, most if not all of the books were conventional (and therefore commercial) works with a patina of literary sophistication—what I called “commercialit.” As I said, I don’t begrudge Sweeney the money. As I also said (but Constant ignored), my worry is that paying such advances for “commercialit” will make it more difficult for truly literary writers—those who might be read 20 years from now--to get their work published by major publishers.

But more importantly, the Creation of a Term to Identify a Publishing Trend You Just Now Noticed is a bad reviewing trope. LeClair shoehorned four different books into a category — “commercialit” — that doesn’t even make sense. So these books are well-written but “safe,” whatever that means?

Since Constant doesn’t specify how the four books are different or how they are literary, I have my doubts that he has read any of them. They are different in subject but similar in their traditional storytelling burnished with M.F.A. sophistication. I take some pains to say what “safe” means and contrast the four first novels with dangerous literary novels by a range of contemporary writers.

This is not a trend that was created by a new generation of writers.

Middlebrow or commercial fiction has been with us since Hawthorne’s “scribbling ladies.” What seems new to me is that young or youngish writers with M.F.A. degrees are producing work that can be marketed as literary when the work is something less than that. My informants in and from M.F.A. programs tell me that much of their instruction now is in how to succeed, not in how to produce original and quality work.

This is not to say that there isn’t an interesting piece to be written about the publishing industry spending too much money on debut novels. But that piece is not a book review. It’s a reported piece, with interviews and supporting evidence and facts and sales numbers.

What Constant calls my “trend piece” had to be at least partly a review (The Nest was the occasion to examine the larger issues.) because the piece was about literary quality, not something that a “reported piece…with facts and sales numbers” would likely address. My “supporting evidence” is the described limitations of Sweeney’s writing. Readers of the other three novels I mentioned can form their own opinions.

Stop trying to make “commercialit” happen, Mr. LeClair. It’s not going to happen.

I regret to say that “commercialit” has already happened. If Constant is not a fledgling, he should know this. If he’s not happy with my term, he could at least admit literary publishing has been commercialized in the last ten years by the takeover of independent literary publishers by large entertainment conglomerates that can pay enormous advances and reap promotional benefits from those sums. Fledgling writers know this, so it’s understandable—if unfortunate--that they would write for the market that exists.

Finally, Mr. LeClair is always happy to be addressed by and receive advice from an experienced editor, but I have to wonder if Mr. Constant had an editor for his piece (as I did for mine in the Daily Beast). I’m a reviewer, not an editor, but it looks to me as if Constant took an immediate dislike to my remarking on Sweeney’s advance and then offered a series of disconnected questions and assertions that didn’t engage in a coherent way with the argument I was making, and that’s what I thought was unfair. At the top of his piece, Constant makes it known that as a co-founder of a review site he is busy, busy, busy writing. This may explain the slapdash structure and even the slightly snarky address of Mr. LeClair. A worrier, I’m concerned that Constant’s piece may represent some or much of web discourse, blog-like writing that is self-edited or that is so rushed to fill space that it seems unedited. So, since Constant takes it upon himself to advise me in his piece, I’ll advise him to find an editor before he “publishes” in the journal of opinion that he co-founded.

Tom LeClair is the author of three critical books, six novels, and hundreds of essays and reviews in nationally circulated literary journals, magazines, and newspapers.

PAUL CONSTANT RESPONDS

Thank you for writing in. As you yourself note, there is absolutely nothing new about this friction between commercial fiction and literary fiction. You’re just slapping a new name on an ancient conflict with your “commercialit” label. For centuries, critics played at this silly gatekeeping game, and it’s part of the reason why literary criticism has withered away in the age of the internet. Book critics must give up on this hoary construct — this author is a sellout; this author is a pure artist — if they expect literary criticism to survive as an art form for the next hundred years.

Advocates of commercial fiction like to frame literary fiction as elitist; advocates of literary fiction tend to argue, as you do, about whether commercial fiction is somehow worth “less” than literary fiction. These arguments are both uninteresting; they imply a binary choice where no binary choice exists. I have never once visited a home where the bookshelves for serious, literary novels are separate from the bookshelves for “commercial” fiction. Most of the avid readers I’ve met somehow manage to read and enjoy both. Why not try to find the value in a book, rather than wringing your hands over the attribution of pointless labels?

Open Books owner John Marshall is in the "closing stages" of selling the shop to a new owner

As the Seattle Review of Books reported back at the beginning of March, John Marshall, owner of the Wallingford poetry-only bookshop Open Books, announced that he was retiring from the bookselling business. In an email to his customers, Marshall indicated that he wanted to sell the bookstore, that sales at Open Books were still strong, and that he believed a new owner could even make something more of the store.

So, one month after the announcement, how does Marshall feel? “Overwhelmed, tired and ecstatic in different degrees at different times,” he says. Marshall and I are sitting in the back room at Open Books just after closing time, talking about the response the store has received. He says within a day and a half of sending the e-mail to the Open Books list, he already had more than 30 offers to purchase the store in his inbox. “Most of [the offers] were well-meaning and thoroughly ill-thought out, and that’s fine,” Marshall says. “People’s hearts are very large organs, but their bank accounts may not be” as large.

“We’re deep in conversation with somebody who I think would be a terrific owner,” Marshall says.

Marshall was completely bowled over by the love that Open Books has received in the past month. “The chagrin and the love and the number of queries about buying the store was absolutely overwhelming — way more than I expected. It’s hard to understand how you’re perceived when you’re on the inside,” he says. It reminded him that “there is a lot of affection for Open Books.” He adds that, sales-wise, “there’s no shot in the arm like saying you’re on the way out.” March sales ended 60 percent above March 2015, which is of course wonderful news, but which adds a whole other difficulty to the process of screening for new owners: Marshall has to keep up with ordering new titles to make up for all the books that are being bought. It’s undoubtedly a good problem to have, but it still takes up time.

So, uh, how’s the sale of the bookstore going? Is there going to still be an Open Books after Marshall retires? “We’re deep in conversation with somebody who I think would be a terrific owner,” Marshall says. He describes the process of the sale as in the “closing stages,” and while he declines to name the prospective owner until all the paperwork is signed, he says the talks entered “lawyer-land” a couple weeks ago, and that she gave her blessing for Marshall to mention the progress in an interview with the Seattle Review of Books.

Marshall describes the prospective new owner of Open Books as “a very regular customer and a very passionate person about poetry, a very thoughtful person about poetry, and a kick to be around. I like her a lot.” He says that he never considered her as a possible buyer of the store, but she was the first person to get in touch with him when he made his announcement. It’s been moving steadily forward ever since. “As well as the talks were going, I was sure I was going to to say something stupid” and ruin the whole thing, Marshall says, but that moment hasn’t happened yet: “last weekend, all sorts of dollar figures were being exchanged.”Now, he says, “I’m much calmer about it, but I still knock on wood. Don’t fuck with the gods — they will turn on you in a moment.”

The idea of Open Books continuing with someone else at the helm excites Marshall. He looks forward to the reinvigoration that a new, younger owner will bring to the store. “I think the internet could be used more as a sales tool and as a medium,” Marshall says. “I grew very tired of throwing readings,” he says, but “I think going back to a reading a week” would probably be advisable. “Reaching out to a broader customer base with the mighty internet” is important, “but getting more bodies in the building” is essential. “I hope the next owner brings community with her, and I’m sure she will.”

Marshall has been thinking a lot about the idea of founder survival, the idea of an institution growing beyond its originator. “If there’s a model — and I really don’t know jack shit about it — I fancy Allan Kornblum, who ran out of Iowa City a very wild press called Toothpaste Press which went on to become Coffee House Press. And then when he retired he moved it along so that the next person was in place for a while and then he stepped aside and he continued to be associated with it.” Does that mean Marshall envisions some kind of a relationship with the bookstore in the future? “To whatever extent it’s valuable, I hope to be connected with Open Books moving forward,” he says.

Open Books is the Seattle Review of Books Bookstore of the Month for April. Every Monday this month, we’ll be talking with Marshall not just about the future of the bookstore, but about its legacy and history, too. More than just about anyone else in Seattle, Marshall has had a front-row seat for Seattle’s poetry scene over the last two decades. It’s an incredible legacy — one that will hopefully continue for years to come.

Notes From the Field - AWP Day 3

Correspondant Rachel Kessler agreed to be our eyes-on-the-ground at the AWP festival this year. Join us for her daily updates as the conference unfolds.

The final day of AWP produces a noticeable thrum from inside the hive. Up and down the teal conference center hallways 14,000 attendees power walk and talk and gesticulate wildly, swinging beige tote bags with great vigor. Drinking fountains were in short supply, although the dehydrated could quench their thirst at one of the many cocktail carts that popped up at noon throughout the venue. Thrifty writers were found purchasing half-racks of beer at a nearby grocery, poetically named “Smart & Final,” sidestepping the day-drinking surge of hockey fans swarming the Staples Center for the game.

Victoria Chang, Kevin Young, Kimiko Hahn and Mark Doty spoke about “What’s the Big Idea? Intention vs. Intuition In the Writing Process” in a panel discussion moderated by Melissa Stein.

Chang explained her process as one, initially, of intuition.

“This book was written in a car, waiting, to pick up a child from school, or some practice or other,” during a time when her father’s brain was deteriorating, her mom was sick, she had a bad boss, and a bunch of kids under the age of five. “I wrote these long lines without punctuation—notes, really. It was an aura, an itch, a feeling nagging… these ghosts hanging around my head. I was examining the slippage of hierarchy and shifting roles of everyday life—you’re the mom so you’re the boss of kids, but your dad is a man so when he is around he is boss, and at work your boss is the boss.” Following this thread led her to a “critical mass of 20 pages of junk typed up,” where a pattern emerged, which provided a form, and more and more intention built on that first impulse.

Kevin Young’s talk took on the form of a list poem. He began:

When I hear the word “intuition,” I think of mother wit.

When I hear mother wit, I think of eyes in the back of the head.

When I hear eyes, I think of second sight.

When I hear second sight, I think of my father —

He went on to tell the story of first learning about his father’s special ability at his funeral. “Second sight is a kind of double-vision, and what you need to edit: seeing the poem’s present, and future,” he said. “Think about how you read something before, and after.” How he read something when his father was alive and then after he was dead. “No one wants to write an elegy. They come unbidden. Necessity is at this poem’s heart.” He read the stunning “Prayer for Black-Eyed Peas,” one of his complex, layered odes to food that rose up from grief. At first, it is not obviously about his dad, but the “you” shifts in the poem, and toward the end he appears:

Holy sister, you are my father

planted along the road

one mile from where he

was born, brought full

circle, almost.

…

Small book of hours, quiet

captain, you are our future

born blind, eyes swole shut,

or sewn.

Hahn read an excerpt from her essay “The Concept Collection: All Bark and No Wow,” comparing the literary traditions of renga, lyric sequence, Pound’s “Cantos,” Whitman’s “Songs of Myself to the music recording industry’s genre of the concept album, where a central theme or storyline exists throughout an entire album, as opposed to a collection of songs. She cautioned, “does a concept allow moving around, though? A ‘project’ can shut off poems. If it is not moving, it is just a project.” The consciously constructed arc can be too tidy. “Marketing potential—BLEH!” Later she said, “language can often be a portal. Words have multiple meanings—loafers, broach…” She described her take on necrophilia in her poem “Exhume” as “unearthing the past and, in a sense, fucking with it.”

Mark Doty traced how a poem begins “as a report on an experience, and in that act of reporting, something begins to shift. There is the speaking part of writing a poem, the announcement on the page; and then the listening – what else comes up?” Once this question opens the poem, he examines the language and sees “a hole I could go down. We realize there is something besides us in the landscape.” A poem can occupy levels of meaning, levels of tonal variation. “The lyric poem is a technology of shift,” he said, “bringing onto the page the questions we can’t answer.”

Over at the bookfair, publishers were slashing prices. They don’t want to schlep home all those books. Some attendees’ eyes might have been bigger than their suitcase expanders. I picked up Anis Mojgani’s gorgeous illustrated prose poem memoir The Pocketknife Bible, from Write Bloody Press and met Rachel McKibbens, a poet who is currently touring the country performing cathartic poetry rituals with a typewriter. Trauma survivors can type their own lines, contributing to a multi-state group poem.

Waywiser books strung up a Trump piñata, offering the opportunity to go at it with a neon orange bat for every book purchased. Eric McHenry, poet laureate of Kansas, was there, signing his new collection Odd Evening. His poem, “Turkeys and Strippers,” ends with these lines:

please raise your phantom hand and take the Phantom Oath with me:

When I have the power I am going to use it differently.

Poet Cody Walker was held up in horrific LA traffic due to some sort of explosion (for a film shoot) on the freeway. As he signed my copy of his new book The Self-Styled No-Child, (which includes this jaw-dropper) I heard the clacketty-clacking of typewriter keys. There was a bearded young man typing up haiku on demand! Business was slow. People were too glazed, or too frantic, or too busy snubbing one another to be bothered with commissions. I leave you with a haiku from Walker’s book:

I’m a mountain and

you’re a new weather pattern

that crushes mountains.

The Sunday Post for April 3, 2016

Is This the End of the Era of the Important, Inappropriate Literary Man?

Jia Tolentino, in a long detailed article in Jezebel, goes inside the Iowa Writers Workshop to examine a man accused. She looks both from the perspective of how historically many men in power used their position for sexual privilege with students, but also how the method of accusation should support believing women, but maybe with a higher bar than anonymity. Fascinating read.

In public, everyone says that Thomas Sayers Ellis, 52, formerly of Case Western and Sarah Lawrence, a visiting professor at the Iowa Writers Workshop this semester, is brilliant. Even the people who find him off-putting and unprofessional tend to agree. He’s charismatic and surprising, a protest poet, a real intellectual, unafraid to cause alarm. His style is enjambed, urgent, and rhythmically afire; in the late ‘80s, he founded the Dark Room Collective to promote writers of color, and he’s been known as an activist ever since. He attracts women; several women I talked to said he had “groupies.” But in late February, a group of women came together to say that he’s abusive, that he preys.

On The 13 Words That Made Me A Writer

Sofia Samatar on the language of fantasy that made her want to write it.

There was a library and it is ashes. Let its long length assemble. These words made me a writer. When I was in middle school, my mother brought home a used paperback copy of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast. “I thought this looked like something you might like,” she said.

Real Talk With RuPaul

E. Alex Jung interviews the most Queenly of the drag queens.

Congratulations on the 100th episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race. With the eighth season, how do you keep things fresh? We're always inspired by the queens. And because it's like a school, we get a new crop of kids every single year — that's how it stays fresh. This year especially, it's the children's Drag Race. These are the kids who grew up watching it, and their whole drag aesthetic comes from the show. So it's an interesting shift. And we knew this would come if we stayed on the air long enough — we'd see what we produced in the public. And they're beautiful! They're smart. We have to actually work harder to stay one step ahead of them.

A Field Guide to Male Intimacy

Max Ross on the father's in his life, and his relationships with them.

When my car’s battery died on a bitterly cold January day, my father refused to come to my apartment in south Minneapolis to give me a jump. He drives a Tesla and claimed (not quite accurately) that using it to power a regular car would cause it to short-circuit. “Plus, it’s nasty outside,” he said, “and, as you know, your father is a wuss.” Luckily my stepfather, Kevin, agreed to help. He is bald, clean-shaven, slender, friendly and handy. An agricultural engineer, he has a master’s degree in weed science and subscribes to journals such as “Wheat Life.” He always knows what time it is. “I’ll be there in 15 minutes,” he said. He arrived at my apartment in 15 minutes.

Notes From the Field - AWP Day 2

Correspondant Rachel Kessler agreed to be our eyes-on-the-ground at the AWP festival this year. Join us for her daily updates as the conference unfolds.

Friday morning at AWP many attendees are moving slowly. Bloodshot eyes abound at the bookfair. This is a result of the many opportunities to drink, dance and attend offsite readings at places like The Ace Hotel’s rooftop deck, featuring a pool the size of a postage stamp that no one was “swimming” in, until suddenly it was full of dudes in what looked like their underwear.

Bro soup aside, choosing what reading to attend in the evening is agony.

“I was standing two feet away from Natalie Diaz and I couldn’t hear a word of her reading!” I heard a woman complain at one.

“I just totally snubbed James Franco in the elevator!” boomed a pant-suited young woman staggering into the hushed The Offing reading.

Evening readings proliferated all across the city, from the swanky downtown public library to somebody’s AirBnB in Silverlake, featuring incredible line-ups of ten, or more, writers crammed into a tiny room, the likes of Danez Smith performing with Seattle’s own Willie Fitzgerald. I fell asleep Thursday night full of tacos and literature, words buzzing around my head, fat bees pollinating my dreams.

Friday morning I slipped into the tail end of a panel “You Don’t Know Me At All: The Creation of Self as Protagonist in Memoir,” and watched Cheryl Strayed smile and chat with a throng of swooning writers. I was there for the next panel “Cunty Faggots: Who Can Say Wut?” with Eileen Myles, Danez Smith, and TC Tolbert. Moderator Christopher Soto began with a “trigger warning, for everything.” He shared a conversation he had with Junot Diaz about the n-word and its use in Oscar Wao which led to the question “how can we write about the realities of queer and trans communities if we can’t use vernacular language?” which was not actually a question, because all of these writers engage some sort of vernacular in their work. Smith described it as a problem of translation, and noted that something is always lost in the act of transcribing a thought to the page anyway, but it is worth the risk.

“As a poet, I can talk about the realities of a black queer individual through plants, if I want – I have metaphors,” Smith said with a smile. “I speak in eight different ‘languages,’ and when I speak in code I use it to invite, or to exclude. Am I supposed to center on the center? In my work I center the margins. When I write I’m purposefully not centering the most average motherfucker. As a reader when I hear vernacular it makes me feel home, validated, that my language is worthy.”

Myles discussed the privilege of success. “My writing is not vernacular, I’m Eileen Myles now. Editors explain to publishers who might be offended, ‘this is her thing.’ Winning, I change the game.”

Graywolf Press publisher Fiona McCrae hosted a reading and conversation with Geoff Dyer, Leslie Jamison, and Maggie Nelson. Each read a short nonfiction excerpt that, by chance, included blood and guts. Dyer described Jackson Pollack’s drunk driving car wreck death as “his final drip painting.” He examined the tortured genius binge-drinking artist myth with word play, sly humor, and sampled language, pivoting on a hilarious deadpan rap, “romantic, fantastic, semi-bombastic,” concluding that this drunk ego-maniac was “a bore, and boring.” Jamison read about wounds from The Empathy Exams, and Nelson on fetuses from The Argonauts. Their conversation turned to the process of writing nonfiction.

“Defensiveness doesn’t have much place,” said Nelson. “I’m offering up my way of thinking as I write.” She paraphrased Deleuze, “part of the horror of speaking and writing is this. What else is writing but to be a traitor to one’ own brain, traitor to one’s sex, to one’s class, to one’s authority? And to be a traitor to writing.” Wittgenstein illustrates the process of thinking with an image of climbing up a ladder where the rung below is discarded, Nelson explained, and this is how she views writing.

Dyer described an essay “as a record of the process of discovery. The book ends exactly at the point I am qualified to write. If I didn’t start writing until I researched and knew everything, it would’ve killed the desire to write.”

Jamison talked about how Dyer’s Out of Sheer Rage was like a bible for her – it gave permission to not know where the writing was going. Dyer laughingly pointed out that this “liberation” could also be “an excuse for laziness.” These three minds are anything but lazy.

The final reading and conversation I attended was possibly the best thing I’ve seen this year. Douglas Kearny, Robin Coste Lewis, and Gregory Pardlo are all stunning poets, and the combined effect of their performances and subsequent discussion blasted the cobwebs out of the rafters in that florescent-lit convention center.

“I’m a pastoral poet in a post-colonial body,” Lewis quipped. “When I see an ocean I can’t look at it without thinking of the Middle Passage. But then, it’s the OCEAN, and beautiful.” Kearny launched into a mind-blowing performance of “a peppy poem about the Middle Passage,” that was a high-wire mash-up of sharks, Disney’s Little Mermaid, Parliament, the funk band not the government. He sang, voiced different characters, moving back and forth to embody the multitudes so rapidly that it exhausted the ASL interpreter who had to tap out with a replacement interpreter.

“Begin a poetry reading with delight,” Kearny introduced his devastating poem, “The Miscarriage.”

“April Fools!” he said when he finished. I can’t do his work justice in this blog post, but Seattle poet and teaching artist Daemond Arrindell likened Kearny’s work on the page to “e.e. cummings on steroids,” and I strongly recommend seeking it out.

The three poets discussed beauty, and joy, and writing gorgeous poems about ugly history.

“Beauty is not pretty,” Lewis said. “In Spanish, there is a saying, roughly translated, “strong, ugly, and formal,’ and that’s a compliment.”

Pardlo spoke about the sense of responsibility to the ancestors, and to community as Cave Canem writers and part of the African Diaspora, but also to the future. Kearny talked about being a component in a larger body, and going towards the thing that is terrifying.

He said, “When your hand trembles above the keyboard—that’s the poem.”

Poetry Flash Now! - Kickstarter Fund Project #13

Every week, the Seattle Review of Books backs a Kickstarter, and writes up why we picked that particular project. Read more about the project here. Suggest a project by writing to kickstarter at this domain, or by using our contact form.

What's the project this week?

Poetry Flash Now!. We've put $20 in as a non-reward backer.

Who is the Creator?

What do they have to say about the project?

Help us build a new online home for our work so that we can better serve & support the literary communities of the West Coast & beyond.

What caught your eye?

Poetry Flash has been around since 1972, a poetry calendar mixed with a literary review. It's a website now, but was used to live in print, and still does live through a reading sereies in Berkely and through organizing festivals. This publication is a labor of love, and just look in the video at all of those poets praising them for keeping it alive.

Now they're looking to update their website and maybe get back to doing some print issues. Surely one of the most advanced tech communities in the world deserves a great website that covers poetry, and knows the history of the region? If you're a tech worker in the Bay Area, of course, here's a great way to build a bridge to the past community.

Why should I back it?

Personally, I'm partial to broadsides, and the $50 level offers a couple options. Of course, there's a tote (there's always a tote with book people), and you can even pre-purchase advertising for upcoming editions.

How's the project doing?

They've just gotten started, but it's a slow start so far. They're asking for $11,800, and don't even have $500. So, if you dig poetry, and you want to support a Bay Area institution, you should consider backing.

Do they have a video?

Kickstarter Fund Stats

- Projects backed: 13

- Funds pledged: $260

- Funds collected: $160

- Unsuccessful pledges: 0

- Fund balance: $780

The virtues of Patience

Published April 01, 2016, at 1:03pm

The latest Dan Clowes comic is a time travel story that at times feels like it's illustrated by the ghost of Jack Kirby. Does Clowes find anything new to say about time travel, or time itself?