Literary Event of the Week: Economic Utopias and Dystopias

Say what you will about our Trumpy times — and we started a book club just to talk about how terrible everything is — it is at least refreshing that people are discussing economic systems. I'm old enough to recall a time (four years ago) when discussing socialism would be enough to end a political career. Now, Democrats are openly calling themselves socialists.

Clearly, the current model of economics — call it neoliberalism, call it libertarian capitalism, call it whatever you'd like — isn't working. It's time to evaluate our economy, throw out what doesn't work, and start over. The best way to investigate our options, of course, is through fiction.

On Saturday the 18th, four local sci-fi writers (Beverly Aarons, Shweta Adhyam, Elizabeth Guizzetti, and Seattle Review of Books columnist Nisi Shawl) will discuss "economic systems in literature and how they relate to America’s current economic system." They will be moderated by a local real estate strategist as they discuss utopia and dystopia in sci-fi, and how those ideas can (and shouldn't) be applied to the real world.

That's the first half of the event. The second half is delightfully participatory, as attendees are invited to "work in groups to create their vision of an economic system they would want to leave to future generations." That's right — you get to start from nothing and figure out how you'd allocate resources in a perfect world.

This is one of the most exciting ideas for a literary event I've heard in months: a chance to learn from fiction and apply those beliefs toward the creation of something new. And even if none of the ideas created at this event lead to the foundation of a new economic model, the hosts are serving free drinks and snacks, so you'll be sure to get something out of the event.

Tashiro Kaplan Artist Lofts, 115 Prefontaine Place S, https://www.eventbrite.com/e/economic-utopias-and-dystopias-tickets-48071143083, 1 pm, free.

The Sunday Post for August 12, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

There’s a ceiling over Seattle again. Obviously the tragedy of wildfires is not this new haze of smoke that separates us from the sun — it’s, well, wildfires. And yet: This is the brief season in which the sky is supposed to soar over us, pleasingly blue and spacious, not a flat, impenetrable ash. Impenetrable is the word — on a typical rainy Seattle day, it’s still possible to imagine the arc of the stars. This haze feels like it goes all the way up.

It’s maybe a stretch to connect that feeling of being locked-in with the set of essays below. But somehow they fit. They’re all about the space around us — the space we move through and live in, space that feels like its ours but really isn’t. ... So maybe it's not such a stretch, for this city where construction is stealing the streets and the sky, and income inequity is measured in astronomical terms.

Who owns the space around us, or thinks they do? And is it too late to take it back?

It is too late, and then again it never is.

This is how we lost the sky

Kenneth Weisbrode and Heather H. Yeung on how we surrendered the sky to surveillance and military hardware. I don’t know exactly how these two writers, one a historian, one a poet, collaborated. But I love to imagine the back-and-forth, facts and imagination arguing with and yielding to each other, that created this conceptually lyrical piece

As human beings were able to look down upon the earth, rather than exclusively upward toward the sky, the relationship between the two became again less vertical, and more contrived. The sky filled with all those orbiting gadgets therefore has not only turned the earth upon its axis multiple times and surrounded it with multiple smaller spheres, but also broken it down into a familiar patchwork of seas, plains, ghettos, “street views” and possibilities of filtered vision that Google Earth presents us so readily with.

We have begun again to bring the sky closer to us; by populating, polluting and managing it increasingly with earthly objects, we are moving the open sky, the nongravitational nothing of space, or the space of the Gods, farther away. We have not only furthered a schizophrenic notion of sky but have also reinscribed a deeper sense of aimlessness.

Who owns the space under cities?

As Elon Musk digs in under Los Angeles, experimental geographer Bradley L. Garrett explores the handover of public space to private enterprise — cities literally selling the ground out from under their citizens’ feet. And it’s not just Elon Musk who’s digging in; turns out the underground is bustling. It makes sense to track what’s happening and to make what’s invisible known.

But who gets to use the map?

Underground has long been a space of public investment, communal infrastructure, exploration and, when required, secret assembly. In many ways subterranean environs have been more democratic than the surface of the Earth, as depicted in Gabriel Tarde’s 1896 utopian novel The Underground Man, in which in which people not only survive but thrive after a “fortunate disaster” forces human kind to burrow.

But as we rush to render our underground world in three dimensions, increasingly it appears we are backing — tacitly or otherwise — private ownership and comprehensive surveillance.

Flood Thy Neighbor

ProPublica investigates a flood in Missouri, and how the Army Corps of Engineers made the decision to build a levee around a single community — more affluent, suburban — forcing waters fatally higher in rural areas nearby. Imagine watching floodwaters take your home and seeing not the implacability of the river, but the ruthlessness of an engineer's cost-benefit analysis.

“It’s been wonderful,” said Valley Park resident Ryan McDougell. “The engineers that came in here and put the levee in, they did a great job. It sucks for the folks down below, because, I mean, this is going to happen every year.”

Minecraft and Me

Finally, architect Will Wiles uses a child’s game to explore how we think about the landscapes around us, from sublimity to sustenance. This is a substantial piece, a tour through the art, literature, and intellectual history of public and private space, and it serves as a sort of refractive lens for the essays above.

And it returns to an idea sparked by that newly claustrophic Seattle sky: how our imagination connects us to the space around us, and how surrendering ownership of that space might mean surrendering something of ourselves, as well.

With Minecraft thus positioned as an improbable mirror, I came to realize I was not creating places that made me happy. Instead I was creating shadowy and forbidding places expressive of the depression that’s dogged me since adolescence. It was an alarming thought: that I was confronting a dark state of mind given architectural outlet. But this was not so simple; it was not just that dark thoughts, in times of creative blockage or emotional stress, had led to dark places. I was in fact pursuing the “delicate equipoise of conflicting emotions,” the ambivalence that Williams describes as characteristic of the sublime.

Whatcha Reading, Jessica Mooney?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Jessica Mooney is a Seattle-based writer. Her criticism, essays, and short stories have appeared in Vol. 1 Brooklyn, The Rumpus, Salon, City Arts Magazine, and of course here, where she reviewed, Kristen Radtke's Imagine Wanting Only This, and Leni Zumas' Red Clocks. Jessica's story "Love Canal" was one of the first pieces of fiction we published. That's not even talking about her non-literary career, in the field of global health for an international nonprofit; her scientific research has been published in Prevention Science and the Journal for Health Disparities Research and Practice. She's received grants from the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture and 4 Culture, and was a previous Made at Hugo House fellow.

What are you reading now?

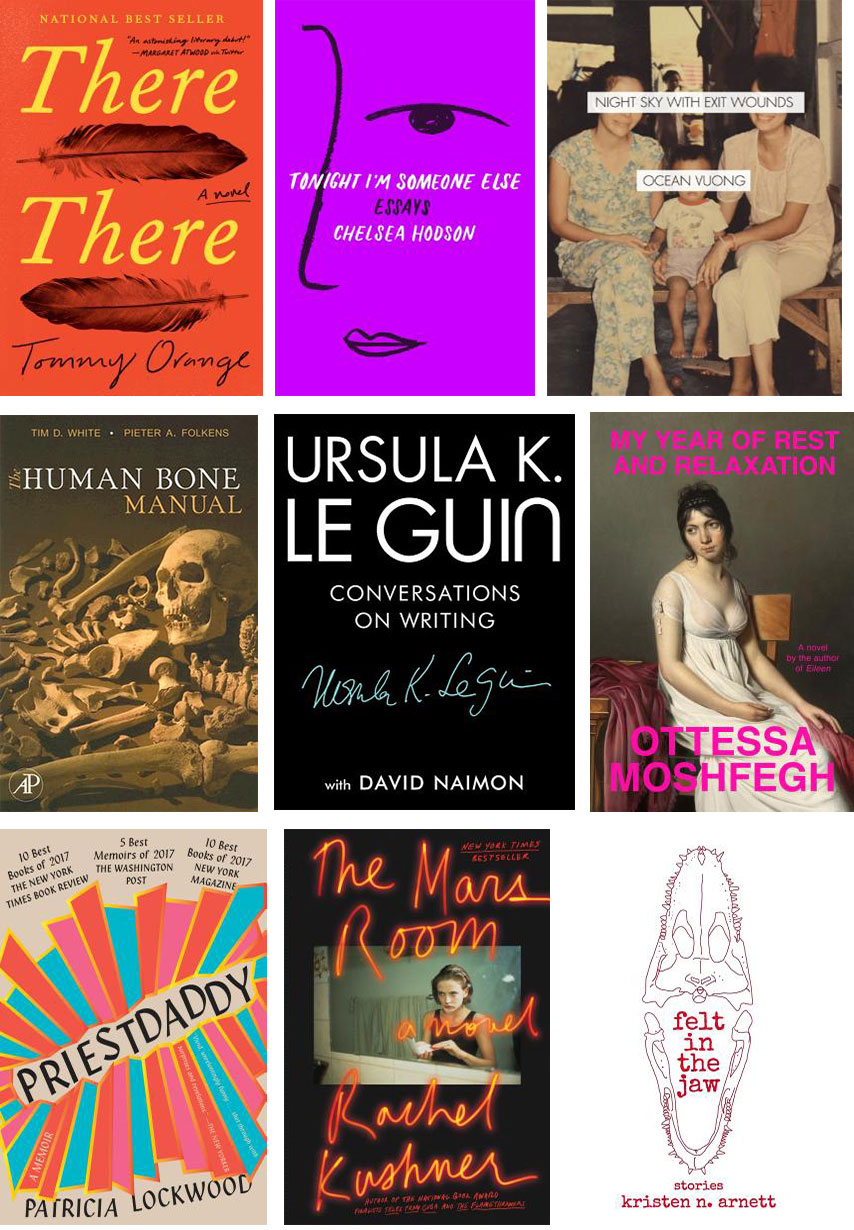

I always have a few books going in rotation. Right now it's There There by Tommy Orange, who is not only an incredibly gifted writer, but a kind human being; Tonight I'm Someone Else by Chelsea Hodson; and I finally picked up Ocean Vuong's Night Sky with Exit Wounds. I'm also reading the Human Bone Manual as research for a novel (great summertime creepy read!), and a few Oliver Sacks essays, which I've done every August the past fseveral years to commemorate his death — "My Periodic Table" just crushes me every time I read it.

What did you read last?

After hearing David Naimon interview Urusla K. Le Guin on on his (very excellent) podcast "Between the Covers", I picked up Conversations on Writing from Tin House Books. I also just finished reading Ottessa Moshfegh's My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Patricia Lockwood's Priestdaddy, both of which I highly recommend for their brilliant off-kilter prose and straight-for-the-jugular humor.

What are you reading next?

Looking forward to Rachel Kushner's Mars Room, Hanif Abdurraqib's They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill Us, and I just ordered Kristen Arnett's Felt in the Jaw, which I can't wait to read with a bottle of BOGO wine, purchased from 7-Eleven, of course, as the good author intended.

The Washington Center for the Book has announced 2018's nominees for the Washington State Book Awards. Go read the full list here, but some nominees that we've reviewed on this site include This Is How It Always Is, Killing Marias, and The Spider and the Fly. Congratulations to all the nominees. The winners will be celebrated on Saturday, October 13th at the downtown branch of the library.

The Help Desk: Reading as snakebite cure

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

What’s your go-to work of fiction for reliable snakebite cures? Hoping for a speedy reply.

Rebecca, Black Canyon

Hi Rebecca!

Sorry that my response came out slower than a tick turd – I've had a busy summer sweating and drinking a firehose of Irish wine (white wine with a shot of whiskey in it, potato chip garnish).

If you want to read your snakebite a book, I recommend Their Eyes Were Watching God, which features rabies, snakebite's natural rival. But if you're looking for a cure, try the Foxfire series – if it doesn't have a reliable cure for snakebite at the very least it'll give you step by step instructions on how to marry the snake what bit you. Then you can check the box marked "honest woman" on Trump's 2020 Whites Only Census.

Kisses,

Cienna

BONUS QUESTION

Dear Cienna,

A while back, someone sent you a question about gender-swapping classic literary characters. As her example, she said she wondered what would happen if you gender-swapped Columbo.

I don’t blame you for not knowing this, but there was a TV show in the late 70s called Mrs. Columbo starring Kate Mulgrew of Star Trek Voyager and Orange is the New Black fame. It didn’t do very well. (Here’s the opening credit sequence.)

Just thought your readers might want to know!

RC, Westwood Village

Dear RC,

Thank you for the note – it was especially timely given the armpit of a summer we're having. My favorite episode so far is "Feelings Can Be Murder," followed closely by "Ladies of the Afternoon," in which Kate Columbo discovers that extortionists are forcing housewives to become prostitutes. BYOIrishwine.

Kisses,

Cienna

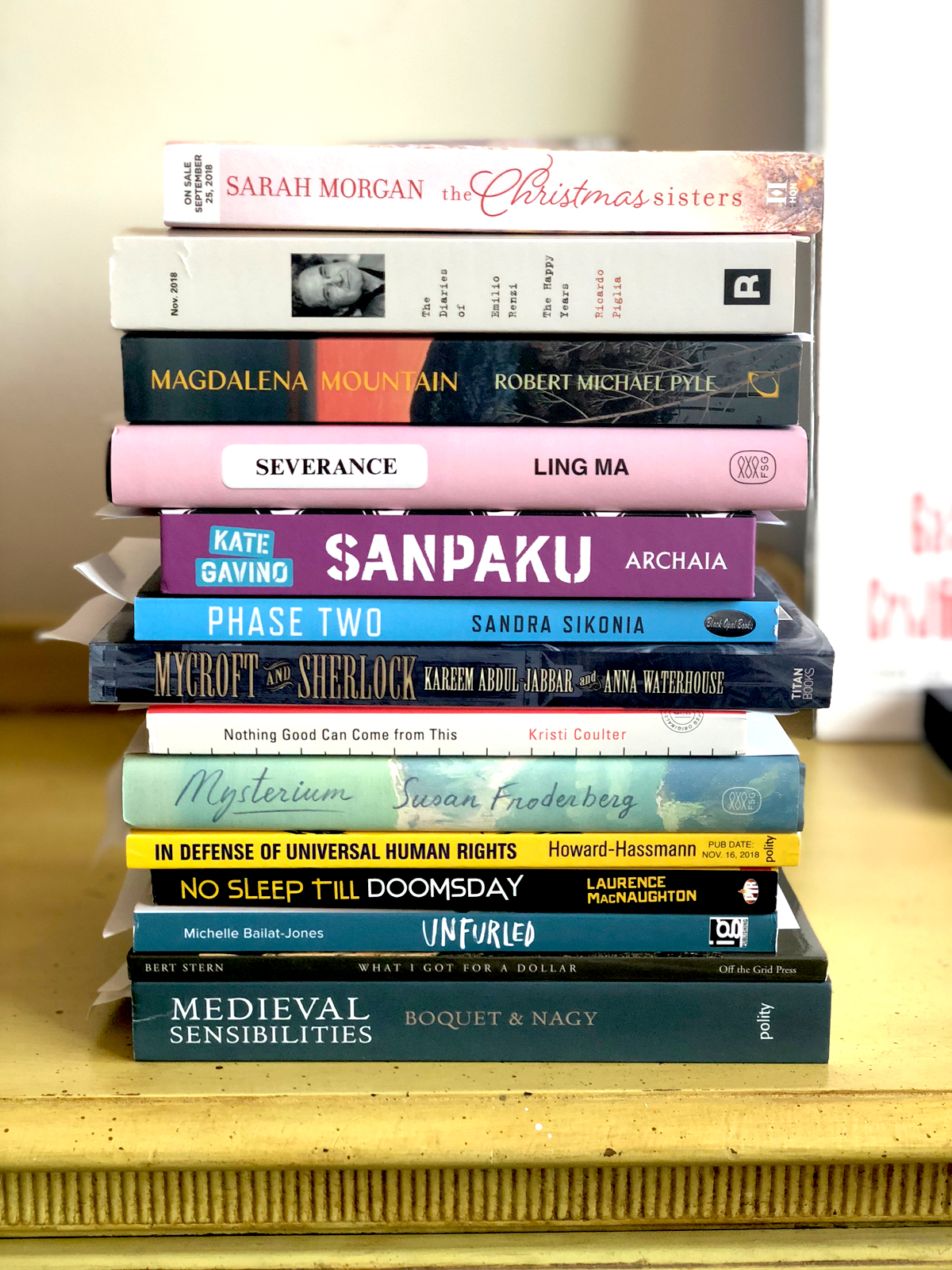

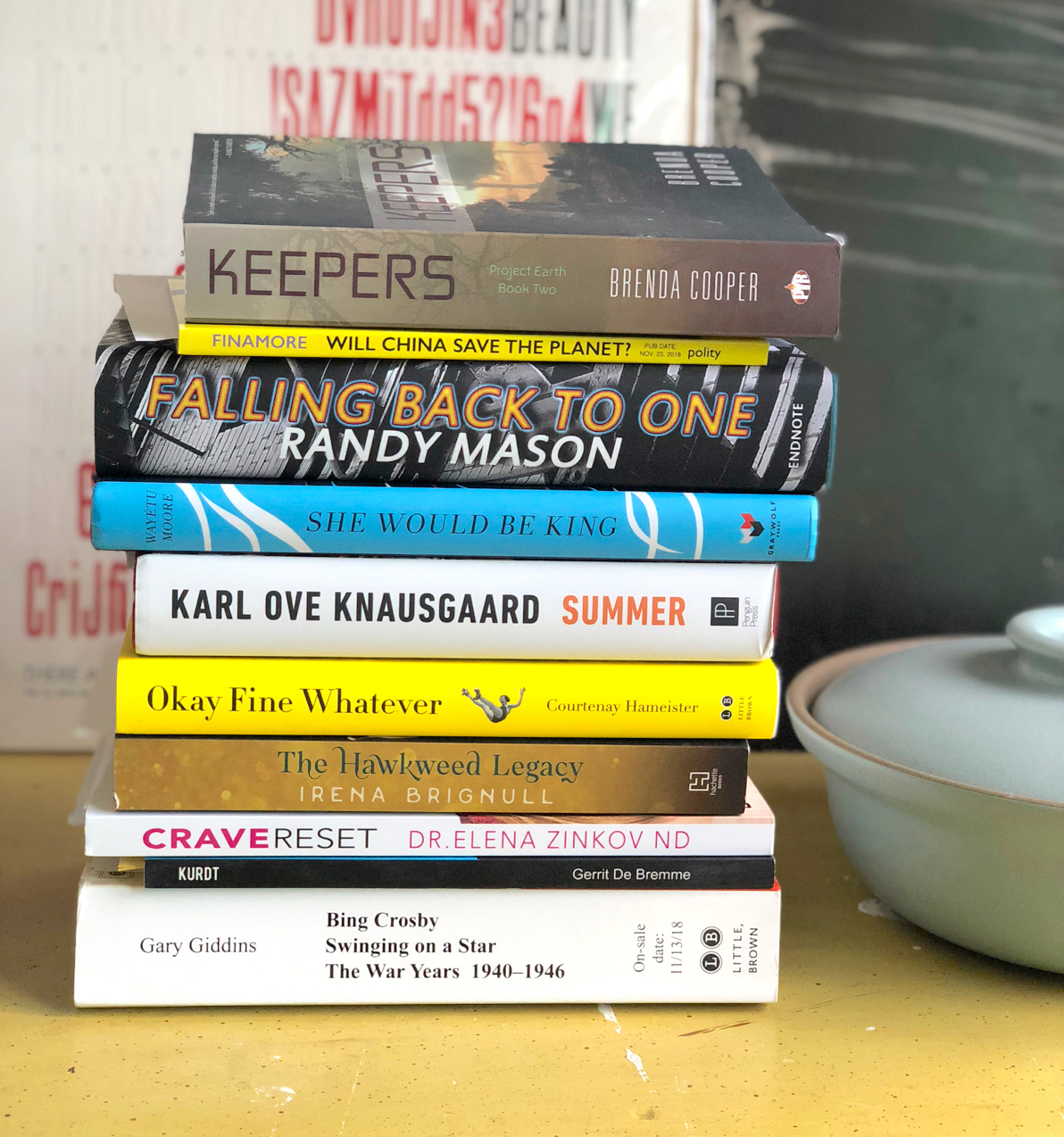

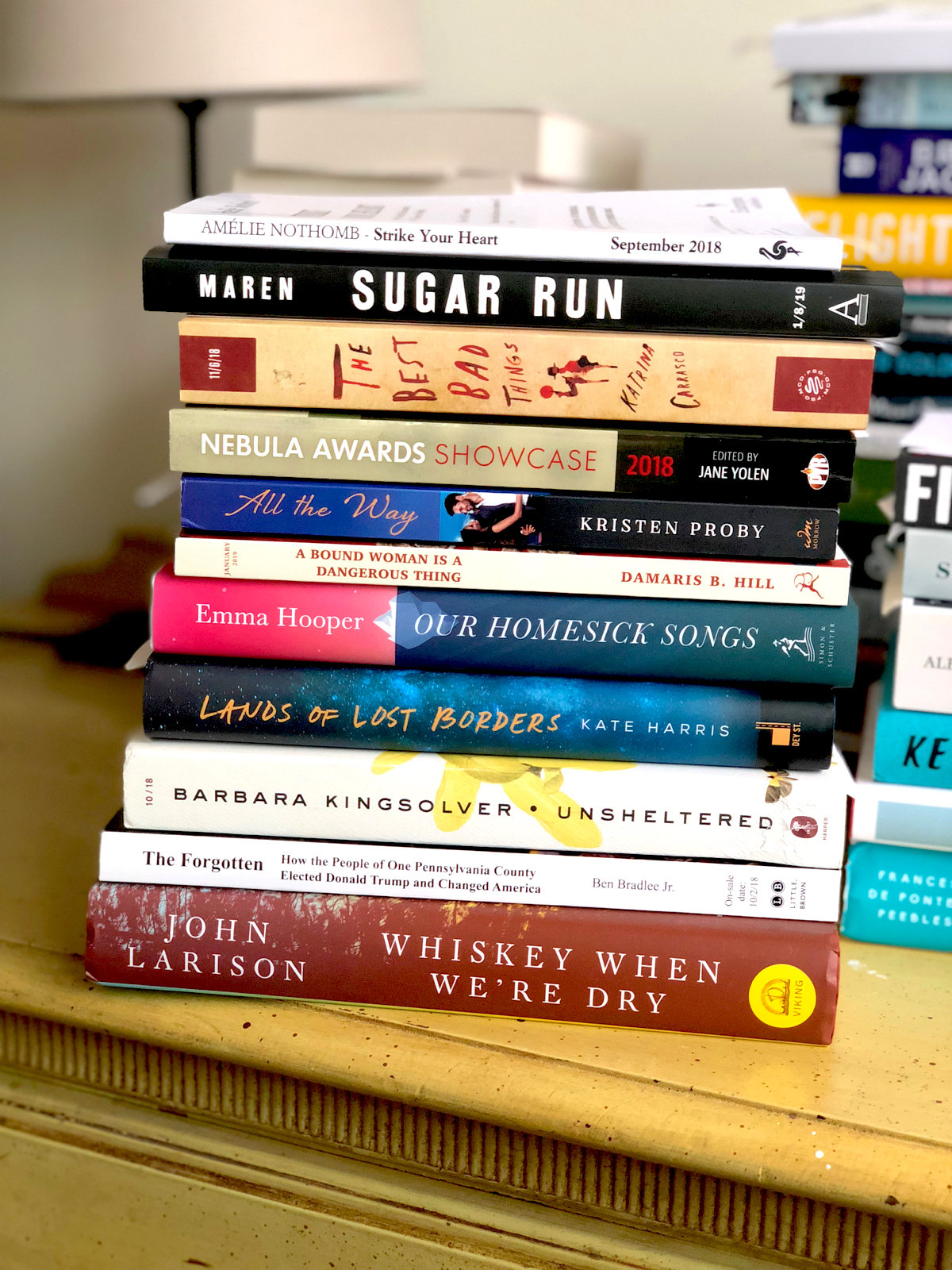

Mail Call for August 10, 2018

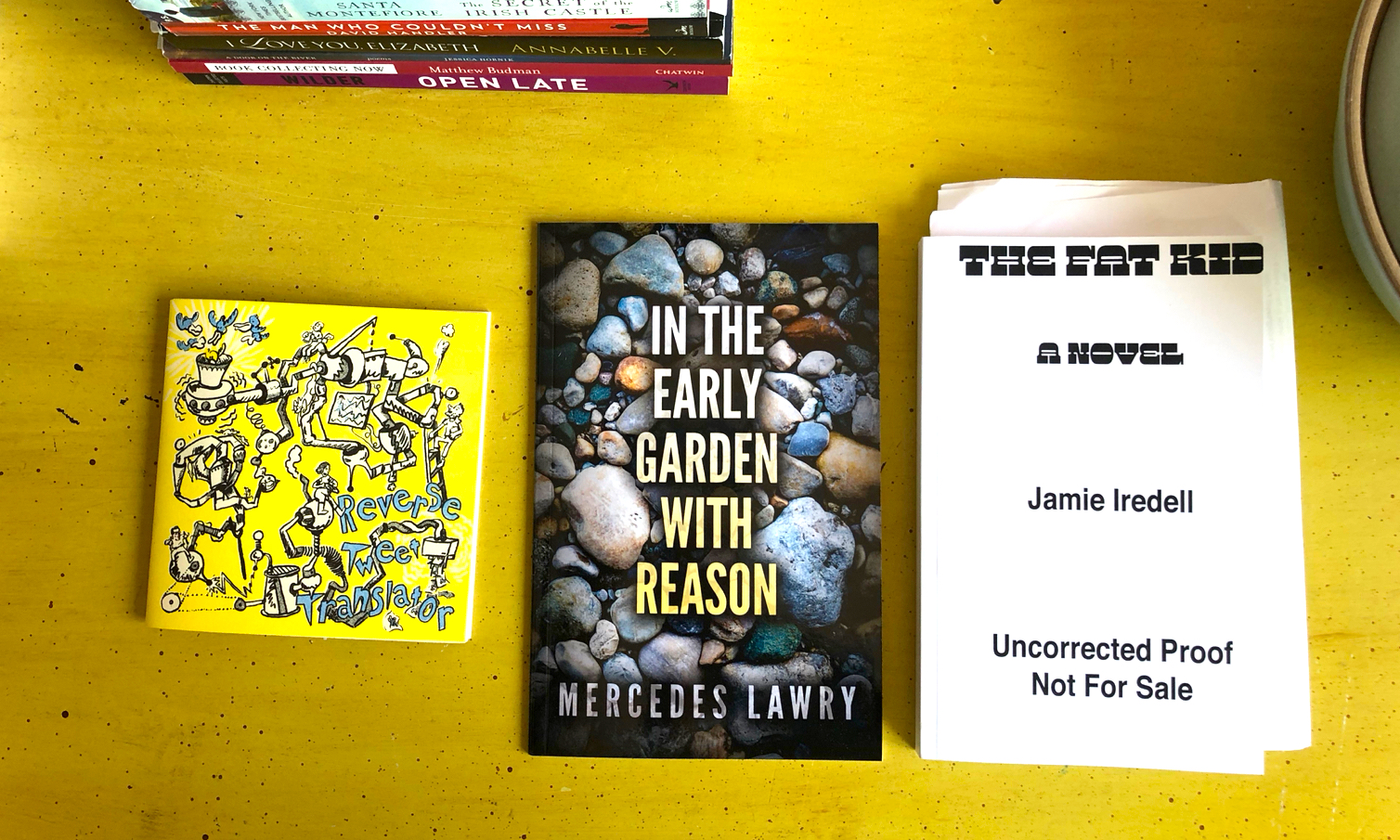

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

Future Alternative Past: a stroll through a columnists memory

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

Sometimes we look forward by looking back

Editor's note: Nisi Shawl is taking a well-deserved vacation in August, so we're presenting this look back at the past twenty-one months of her look into SFFH. We feel so lucky to have such an astute observer, and participator, of SFFH culture leading our wrap-up. She'll be back on the second Thursday in September with a new column. If you really need more Nisi, in the meantime, you may consider picking up her novel Everfair (Paul Constant's review is here).

Nisi started in November of 2016 — a blessedly positive event in a season of frustration and outrage — writing about the importance of conventions in SFFH. Her second column looked at year-end best-of lists, and then she kicked off 2017 asking a question pertinent on everybody's mind: utopia or a dystopia?

Interviewers sometimes ask me which mode of science fiction is easier to write: Utopia or dystopia? Look around you, I answer. Dystopian fiction is basically mimetic (realistic) fiction. It’s way, way too sodding easy to depict a scenario so ubiquitous; I choose to get my jollies envisioning the Utopian coolness that could be.

She wrote about love (desire, eroticism, and simple pleasures), and she wrote about learning to write. She wrote about older pieces of SF holding up to modern scrutiny, and about the environment. She wrote about immortality, and how sub-genres of SF make claims to "literary" legitimacy.

In another of her writers' workshop columns, she wrote about conflict vs. tension:

Something’s got to happen. Who wants to read about happy characters dwelling contentedly in the land of status quo with no worries, no desires, no agendas? Paying customers prefer action. We authors love our characters (who are often facets of our own selves), but in pursuit of stories others will read we torture and provoke them, prod them, plumb their depths.

She covered (snort) that thing by which we all judge books.

She talked about body image and fat-positivity, and fatphobia, in the genre, and followed that column up by looking at the lush, verdant, and sometimes disgusting, visage of food in space. What we wear in the future has been the topic of books she's covered, as has music. And of course, how our favorite characters learn — think more Isle of Roke than Hogwarts.

If you don't have a familiar, you may have a plain-old animal (this column includes a picture of Nisi's cat, Minnie, and apparently those sorts of things are popular on the internet), and if you are a cat and snort some catnip, you might like the topic of her column about drugs.

She talked about sports, and just last month, the end of the world.

One of her most powerful columns, published last May, talked candidly about inclusion:

I hate “diversity.” Diversity is a white person word. A male, cis, het, able-bodied word. A word that presumes its own characteristics are the world’s default settings even as it seeks to leaven them with “otherness.” That arrogant lack of awareness is why I prefer to talk about inclusiveness in SFFH. Inclusiveness means including in what you’re doing those whose traits differ from the dominant paradigm, not just sprinkling them on top. Inclusiveness allows for the possibility that those included have some say in the matter of where and when they’re included, and how, and whether they’ll want to reciprocate. It de-centers and de-privileges the unmarked state.

We recommend spending some time looking back — of course, in every column are reviews of books you may have missed the first time around. One of the greatest gifts of a columnist is seeing the world through their eyes, and there is no better guide to the world of SFFH than a voracious reader like Nisi. Enjoy this look back — it should be plenty to hold you over until September, but it's okay if not; it would be great if you miss her this month and can't wait for her return. We feel the same way.

Thursday Comics Hangover: Two number 2s

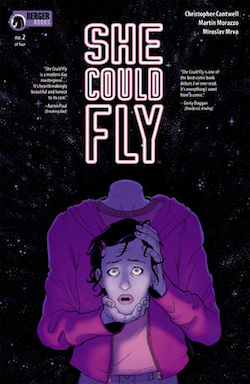

Halt and Catch Fire creator and showrunner Christopher Cantwell has a new comic called She Could Fly. The story begins in very familiar territory for a comic — in a world like our own, a young woman gains the power of flight — but the premise immediately goes south when the woman explodes in midair. Nobody knows who she is or how she could fly or why she exploded. Internet conspiracy theories sprout overnight like so many blackberry bushes.

Luna, the star of She Could Fly, is obsessed with the flying woman. In the second issue of the book, which came out yesterday, Luna's guidance counselor says "I want you to give this flying woman a rest." Luna doesn't listen to her — and for some reason, the guidance counselor has the head of a cat and a human body.

Luna, it seems, is hallucinating. She imagines demons attacking her. She imagines becoming a demon (sample dialogue: "I AM EVIL! I AM EVIL! I AM EVIL! I AM EVIL!") and she keeps digging deeper into the story of the flying woman. Meanwhile, a moustachioed rogue agent is also looking for the truth. The up-and-coming cartoonist Martin Morazzo renders Luna's reality with a high level of detail, making it even harder to tell the difference between what's real and what's fictional in Luna's world. Halfway through She Could Fly, I can't tell you what the book's about. But I can tell you that it's going somewhere interesting.

Speaking of second issues, the second issue of Chew artist Rob Guillory's new book Farmhand was published yesterday. Where She Could Fly continues to complicate the psychological layering of the series by obfuscating the narrative, Farmhand introduces characters and tensions with a refreshing directness.

Farmhand is the ultimate body horror comic: it's about a scientist who figures out how to grow new human body parts on trees. The technology, at first, seems like a godsend. In the second issue, a disfigured woman grafts a plant-based nose onto her face. But everything is more than a little creepy: a bush full of human hands isn't exactly a comforting image.

Guillory is setting up Farmhand to be a drama between an estranged son and his father. (The family tree jokes write themselves.) But there's also some fascinating depictions of addiction and recovery, as well as more than a little economic anxiety. It's the details here that make Farmhand so enjoyable. Even though Guillory is great at getting to the point in a hurry, he understands that we have to take the long way around a story every now and again.

Ron Charles at the Washington Post reports that YA author John Green is fronting a charge to bring a new format of book to America.

These Penguin Minis from Penguin Young Readers are not only smaller than you’re used to, they’re also horizontal. You read these little books by flipping the pages up rather than turning them across. It’s meant to be a one-handed maneuver, like swiping a screen.

Green first saw these so-called "Flipbacks" in the Netherlands, and he tells Charles he finds the format to be "really usable and super-portable.”

Reinventing the book — one of our species' oldest and best technologies — is a tall order. But I'd love to give the flipback format a try. When I'm on a standing-room-only light rail train, I'd genuinely enjoy a small, one-handed reading format that isn't a hideous glowing screen or a weird flickering e-ink reader. Even mass-market paperbacks are too cumbersome for Seattle's hyper-busy public transit. Maybe flipbacks will do the trick.

Snowflakes

Published August 08, 2018, at 12:00pm

Alicia Kopf's experimental novel about a character named Alicia Kopf runs cold, then hot.

Exit Interview: Seattle cartoonist Eroyn Franklin is leaving Short Run in good hands

Eroyn Franklin is consistently one of the most interesting cartoonists in Seattle. Anyone who has seen her 2010 comic Detained, which documents the living conditions in Washington's immigrant detention centers via a comic laid out in a single unbroken scroll of paper, knows that she's formally inventive and narratively interested in what it means to be a human in the world.

But Franklin has perhaps been best-known for the last few years as one of the cofounders and organizers of Seattle's amazing Short Run minicomics and arts festival. With fellow cofounder Kelly Froh, Franklin has always been right in the thick of the festival, greeting guests and solving problems as thousands of people buy and sell comics around her.

Last week, Franklin announced that after seven years she was retiring from her role as a Short Run organizer to focus on her comics work. This week, I met with Franklin at a coffeeshop to talk about the process of leaving Short Run, why she's confident in the organization's future, and what she's working on now. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

You can keep track of Franklin's work and appearances through her website.

Franklin photographed at the Short Run afterparty in 2017.

Could you talk about how you came to realize that you were ready to move on from Short Run, and what the process of leaving was like?

I had definitely been feeling for the past two years that it was getting really hard for me to manage the responsibility of Short Run — that it was getting so big, and more work was being added every year, but there wasn't necessarily much more compensation for that. So I was having to work a lot of different freelance jobs in order to make sure that I could be a part of this creative project. And it does feel like its own creative project.

But that meant that other areas of my life were kind of suffering. I wasn't making as many books as I wanted to make. I was always anxious and depressed and swinging back and forth pretty wildly. I knew that something had to change, and it took something like two years to realize that leaving Short Run was something that had to happen. I just had to leave in order to give myself the space to pay attention to the other aspects of my life that I had set aside.

I started talking about it in earnest last summer. [Short Run cofounder Kelly Froh and I] had conversations up until [last year's] Short Run that were like, 'I'm pretty sure that I'm going to leave. Kelly, whatever you want to do is perfectly fine. If this is too much for you to do on your own, we all understand. The community understands this is a big effort.'

But right after Short Run she was like, 'I can't not do this. It was so perfect this year — it ran so smoothly and it was so huge and everything was vibrant.' For me, it was a wonderful way to say goodbye because I could experience this peak of joy, but for her it really made it clear that she needed to continue on.

So we worked together to help her build a board that would sustain the vision that she had and that we had.

Do you think about what might have happened if Kelly wanted to quit, too?

Yeah, it would definitely break my heart if Short Run folded. But heartbreak is also a part of life. Kelly and I have always talked about how our friendship comes before anything else — that we are a team that runs this organization, but really it's our friendship that makes all that possible.

So I was looking out for her and she was looking out for me. She never made me feel guilty about leaving. She never tried to pressure me to stay. She understood it. And I know she is going through a lot of the same feelings that I have. We both have problems with anxiety and depression and it is overwhelming.

So yes, I would have been okay if she decided to shut it down, of course, because that would've been her decision for herself. But it's so great to have this legacy that I get to be a part of. And I am one of the cofounders of this great, magical experience.

So what's happened since then?

Immediately afterwards, I had one day where I felt free. I could imagine myself just walking into the studio and just writing an entire book. But in reality I hit a pretty deep depression for about three months, and I just felt like all of my identity was wrapped up in Short Run. It's my community. It's my friends. It's everything. And losing that, all of a sudden — the reality of it, and what that meant, really dragged me down.

And then I walked into the studio to work on this book that was actually supposed to be a collaboration with my ex. And it turns out it's really hard to write when you're just crying all day. So it took me awhile to set that aside.

I went to an artist residency at Caldera Arts, which is in central Oregon, and so I got to spend a month in an A-frame cabin and my only obligations were to make art, walk around, and do whatever I wanted. It was so freeing. [Before Caldera,] I was so depressed that I thought I was going to give up on art, give up on writing, give up on comics, and everything was just going into the trash.

But the second day I was walking around and something just clicked. All of a sudden I had all these new stories flood my brain. They're all fiction, and I've worked a lot in nonfiction so it's really wonderful to be able to just make up these stories and go for walks with my characters and have conversations with them. That was a really healing experience, and it allowed me to also set aside the project that was supposed to be a collaboration, which I do want to come back to when it's not so close to the breakup.

What was it like putting together the board that would help move Short Run into the future?

Kelly and I had a lot of conversations about who would be a part of it and what they would contribute. I think that the board she's chosen is amazing. All the people are super-active and they know a lot about nonprofits, and about the comics world, about art. It feels really solid.

What part of your time at Short Run are you proudest of?

I'm really happy about the smaller programs that Short Run has built. Everyone thinks of the festival and it's this huge event where we have, you know, thousands of people attending and it fills all of Fisher Pavilion. We have 300 artists, and so it's like this big dramatic thing.

But we also have all these smaller programs — we have the Micropress which publishes anthologies; we have the Dash Grant, which is a small grant for self-publishers; we have our educational component. And we also have the Trailer Blaze, which is the ladies comics residency at Sou'wester, which is a vintage trailer park in Seaview, Washington.

That residency is for women comics creators, and that was really important to us because when we first started Short Run, it was a lot of dudes. I remember when Kelly had to make the table map and she had to lay out where everyone would sit at the festival and she'd put three guys and then one woman and three guys and then one woman. It was just so difficult to figure out how to show representation of women.

That is absolutely not true anymore in any way. It's so easy. We're basically 50 percent women and it's not hard — it's not like we're trying anymore. There are so many more female creators in the field. So anyway, the residency is for women comics creators. It's so wonderful because it's a combination of giving women time and space to dedicate themselves to their work, which we often don't have in our daily lives because we have so many distractions.

It's just a very supportive environment. I remember one time at Trailer Blaze in the first year. Without any urging of any kind, we started this thing that we later called "The Compliment Avalanche," where we just went around and told stories about how wonderful the people were. Each woman got to be spotlighted for a few minutes, and it was just such a wonderful loving experience.

So what are you working on now?

Right now I'm working on a bunch of stuff. I just finished a minicomic that's actually an illustrated zine called Vantage #3, and it documents all the walks that I did during that residency I was just talking about at Caldera Arts. While I was there I was really inspired by the environment — both the natural world and the actual space that I was staying in, the A-frame cabin. I wanted to incorporate that into a story, and I wasn't quite sure what I was going to do when I set foot in the A-frame cabin, but I immediately fell in love and realized 'this is a character in this story.'

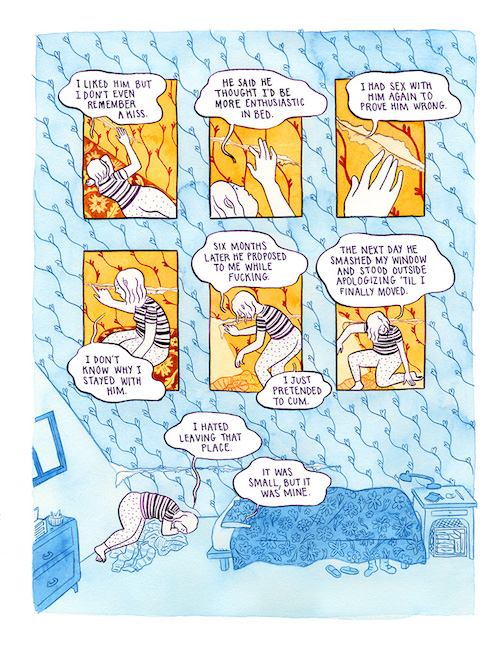

I think after #metoo, everyone was trying to find an authentic way to talk about how misogyny is rampant in our culture. I wanted to create a story about it, and I wanted it to reflect my personal experiences but also be fiction. And so I started out with this woman who basically goes and lives in this A-frame cabin. She's trying to get away from all the men in her life. She starts having conversations with the environment, with the natural setting and with the cabin, and they become characters on their own and they develop.

She develops a relationship with space that becomes more intimate than her relationships with men, and more loving. And that's as far as I can go into a description of that without giving it all away.

A page from Vantage #3.

It seems like a lot of your work, especially Detained, is about people in space — where they are and how those places affect them and how they affect where they are, and all that. So it seems like this is a continuation of that theme on a very literal level.

Yeah.

Does it feel like working in fiction has enabled you to get a little deeper into those themes?

In some ways, fiction makes it so that I can be almost more intentional in the purpose of the story. When I'm drawing from my own life or from non-fiction stories, I'm indebted to the people who are a part of it. With fiction I can go in any direction I want to. So it does free me up to explore different themes that maybe aren't going to be present in every story. I feel like there's a lot of freedom in fiction that I haven't paid attention to in a long time.

Are you going to still go to Short Run this year?

I'm definitely going to Short Run and I'm going to be tabling for me and Kelly as usual. And of course I know all her books so I'll be able to sling them pretty well. I definitely imagine that I will be a part of Short Run and all the events that the organization puts on. I've been going to the Summer Schools that are going on right now.

They put on amazing events! They just do such a good job, of course I'm going to be a part of it. And some of my best friends are the fantastic women who are the building blocks of this organization. So I'll continue to be in their lives and in Short Run's life forever and ever and always.

Was there anything else you want our readers to know?

Yeah. I'd like to reiterate something that I said in my retirement letter, which is that Short Run will exist without me, but it won't exist without all you. People need to support this organization that has affected their lives. Maybe that's coming to events. Maybe that's donated time. But especially right now the organization does need support, so please give whatever you can in whatever shape or form it takes. I want to see it continue for another decade.

Kickstart the first Shout Your Abortion book!

Back in 2016, I wrote about local advocacy organization Shout Your Abortion's very first zine. "The first issue of #ShoutYourAbortion celebrates a part of the abortion story that has long been too quiet," I wrote. I speculated that "maybe one day, these [pieces] will be collected into a book — something you can put on your shelf and keep on display forever."

That day is fast approaching. Yesterday, Shout Your Abortion founder Amelia Bonow announced that SYA is launching a Kickstarter to publish their first anthology volume. Here's a video:

Contributors include Lindy West, Lesley Hazleton, Angela Garbes, Robyn Jordan, Emily Nokes, Kelly O, and many more. At about 24 hours into the campaign, the book is already almost halfway funded. But simply funding the book shouldn't be the goal — it's important to get the voices of SYA into bookstores around the country, into the hands of women who might not know that it's okay to celebrate their reproductive health and to shout their abortions to the world. If you're interested in this book, I'd suggest funding the Kickstarter now, to demonstrate your support. The more copies they presell, the more copies they'll be able to bring into the world.

The Russia stuff

Published August 07, 2018, at 11:55am

Keith Gessen reads at Elliott Bay Book Company tomorrow. His novel A Terrible Country is a hilarious and heartfelt account of a global empire in sad decline. No, not THAT global empire. The other one.

Shall Not Be Infringed

We dove under a table, my bag

clutched in one hand, your hand in the other.

House rules: no politics. Who had slipped,

stepped aside, maybe only moments? Left

the door unbounced this summer

night? He fired, pointing first

at the other end of the room, shed

one weapon for another. Is that

how we had time to dive? We threw

our bodies down like castoff shoes,

like trash. He walked out. This happened, it

happens, it will happen again, maybe to me,

maybe to you, waking. Down he went

through each room in my house of sleep, from

attic to basement shooting out the lamps

making permanent the dark.

Zadie Smith and Pete Souza added to Seattle Arts & Lectures calendar

What we love about the SAL season is that it's curated not just speaker-by-speaker, but as an arc — they think carefully about how different speakers fit together, and what it looks like to subscribe to a series (like Women You Need to Know or Literary Arts) or create a series of your own. This year, it's about joining the national discourse — about, as associate director Rebecca Hoogs put it, using story, language and conversation to "cross the bridges that divide us."

That's how you create a series that includes Kara Swisher, one of the tech industry's sharpest-eyed journalists; Pete Souza; Anthony Ray Hinton, who spent 30 years on death row for a crime he didn't commit; Tayari Jones, author of an acclaimed novel about race and false accusations; Valeria Luiselli, who built an essay around her conversations with undocumented Latin American children facing deportation. The speakers who make up this SAL season are brilliant at their craft and are using it to engage and to help us do the same. Get tickets today, and make these events part of your own conversation with the world.

Sponsors like Seattle Arts & Lectures bring great events, services, and books in front of our readers — all the while helping us put book news and reviews up every single day. It's a virtuous cycle, and you can be part of it: Got an event, a book, or a residency you'd like to promote? Reserve one of the remaining 2018 slots before they’re gone.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from August 6th - August 12th

Monday, August 6: Nothing Good Can Come From This Reading

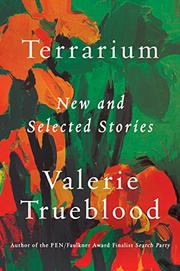

The essay collection Nothing Good Can Come From This is a much-anticipated book by Kristi Coulter, whose essay about quitting drinking became a huge internet sensation. Now, she's being compared to writers like David Sedaris, which is hugely unfair but which publisher PR reps (and bad book reviewers) love to do to essayists who are funny. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Tuesday, August 7: Terrarium Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Wednesday August 8: A Terrible Country Reading

Keith Gessen is a journalist, an editor, and a damned fine novelist. You might know him as a driving force behind the magazine N+1, or as a brilliant cultural critic, or an early advocate of the Occupy movement. Tonight, he's in town to read from his new novel A Terrible Country, which is about a young man who returns to his home country of Russia in order to care for his ailing grandmother. After the reading, I'll be interviewing Gessen onstage. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Thursday, August 9: Word Works

Ben Lerner is a MacArthur "Genius"-winning poet who draws parallels between science and poetry in his work. His work is brainy and it requires work. He is exactly the kind of writer who should be hosting one of Hugo House's Word Works series. Frye Art Museum. 704 Terry Ave., 622-9250, http://fryemuseum.org, 7 pm, $15.Friday, August 10: Choose Your Own Disaster Reading

Dana Schwartz's Choose Your Own Disaster is a comedic memoir "about the millennial experience and modern feminism." It also is in the form of a personality test. Third Place Books Ravenna, 6504 20th Ave NE, 525-2347 http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Sunday, August 12: Prairie Fires Reading

Caroline Fraser's Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle award and it wound up on many year-end best-of lists. And now she's making a Sunday afternoon appearance at Elliott Bay Book Company. These readings are usually more intimate than the weeknight events, so you might have an opportunity to enjoy more time and attention from an award-winning author. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Terrarium reading at Elliott Bay Book Company

Aside from having a fantastic name, Valerie Trueblood is best known as one of Seattle's most accomplished short story writers. She has been on shortlists for the PEN Faulkner Award and the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Prize, and her work has been praised in all the usual New York media outlets.

But if you're not the kind of person who is moved by accolades — and, really, who can blame you? — then perhaps Roxane Gay's seal of approval might inspire you to pick up Trueblood's work? Gay says Trueblood's writing is "bursting with a genuine violence of health and strength of will that make each of her stories so engaging." Gay continues, "What I love most about her writing is how her stories are, at once bittersweet, joyful and mournful in equal measure."

After about four years out of the spotlight, Trueblood is returning with Terrarium, a career-spanning collection that brings together her classic work and dozens of new stories. It's a statement piece, a book that seems to be intended to mark her as a real American master of the short story.

Terrarium is made up of the best stories from Trueblood's three previous collections, and 30 new stories. These are stories with killer first lines ("She was a young married woman who fell in love.") and final images that will leave your mouth hanging open (like the description of the whorls of a tornado as "a fingerprint big as God's.")

In the chronological arrangement of the stories in Terrarium, you can follow the arc of Trueblood's career, and change is definitely afoot. Trueblood is getting more and more minimalist in her work. The rambling earlier works that considered the journey to be just as important as the destination give way to tiny one or two pages stories. Trueblood is distilling the idea of fiction down to something pocket-sized.

Tomorrow night, Trueblood celebrates Terrarium's release day at Elliott Bay Book Company with a reading and a little celebration. If Terrarium becomes as well-regarded as it should, this might be your last opportunity to say you saw her read before she became a celebrity in the world of short fiction. Seattle needs to step up and embrace Trueblood before the rest of the world tries to claim her.

Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Mail Call for August 5, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

The Sunday Post for August 5, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Biking thousands of miles to my friends’ weddings, I found what makes me free

Past Seattle Review of Books contributor Tessa Hulls’s essay on biking to weddings — I mean, biking hundreds of miles to weddings, not biking-downtown-from-Ballard — is an eloquent exploration of independence. Hulls built her own machine to leave an engagement that was overcast with anger. Then she used it to establish a relationship with the world in which the boundaries are entirely hers, as much as they ever can be.

Ever since I made that first escape, my body has felt too small to contain its sense of wonder for the world and for how much of it I have been able to see. In all the places I’ve been and the moments I’ve witnessed, I’ve almost always been alone. I relish solitude, but I have often longed for a partner to help shoulder some of the beauty and the weight. There have been men over the years — men I shared sleeping bags with, men with whom I watched the Northern Lights, men who brewed coffee as I broke down the tent. But none of them ever made me feel free.

We Must Let Go of the Whale Who Will Not Let Go of Her Dead Baby

The internet took poets seriously last week, to the surprise and dismay of the poets involved. Also, a baby whale died. Charles Mudede gently deflates our collective mourning for the whale and its mom, and the poetry they inspired, with the driest kind of wit, the kind that comes from a too-painfully-perfect understanding.

The poem is by Paul E. Nelson. It's not bad at all (though I'm no expert in such matters). It contains one or two respectable lines. It has some restraint, though the bit about the princess whale is almost a bit much. It does its best not to speak for the grieving sea mother, whose name is Tahlequah (or J35). Nevertheless the poem itself is a sure sign that things have really gone too far. The whales' over-grieving has become over-reading and over-writing for the language ape.

Community Plumbing

Mudede takes some of the air out of Seattle sentimentality, including our desire to carry the Showbox and other beloved businesses on our rostrums as we swim through the Sound … Shannon Mattern’s essay about Crest True Value Hardware, an independent hardware store in Brooklyn, puts the air back (a bit) — reminding us that our regret isn’t just about sentiment.

Building a small business is a craft, itself: choosing products that both sell and offer real value to the customer; designing the layout and making sure it evolves over time as the business does; engaging with the community. Independent businesses bring something to a sale beyond the exchange of cash for commodity. And that’s not just romance or mawkishness — Mattern isn’t a hipster elegist; she has hardware heritage, and a killer knowledge of general-store history to share. A long read but an excellent counterbalance.

(Hat tip to Tim Carmody at Kottke.org for this one.)

In Joe’s telling, there is a reciprocal relation between the hardware store and the neighborhood it supplies. Those plank floors might seem as if they were buried beneath the old tile, just waiting to be exposed, but actually the wood was reclaimed from nearby buildings damaged by Hurricane Sandy. “We wear those floors almost like a badge of honor,” he told me. Similarly, the counters were sourced from a former employee (now a local firefighter) who was renovating his home. “That live edge: you can tell they’ve been somewhere,” Joe said. “And for the last hundred years they’ve lived less than a quarter-mile away, holding up somebody’s building.”

This is a vision of the hardware store as episteme. It holds (and organizes) the tools, values, and knowledges that bind a community and define a worldview. There’s a material and social sensibility embodied in the store, its stuff, and its service, and reflected in the diverse clientele. That might sound a bit lofty for a commercial establishment that sells sharp objects and toxic chemicals. But the ethos is palpable. (And profitable, too.)