Shipwrecks, sailboats, and stories of the sea

Both books are a blast to read, and this week you can hear Hinman tell those stories in person. She's at Third Place Books in Seward Park on June 7, and at King's Books in Tacoma on June 9. By all accounts, she's a fabulous storyteller. Don't miss the chance to hear her. Before you go, check out the sample (and more information about Hinman's books) on our sponsor page.

Sponsors like Wendy Hinman bring great events and new releases to your attention and make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? If you have a book, event, or opportunity you’d like to get in front of our readers, find out more, or check available dates and reserve a spot.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from June 4 - June 10

Monday, June 4: Planet Funny Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Tuesday, June 5: Orca Reading

Did you know that June is Orca Awareness Month? See? You’re learning something already. At this Town Hall event, environmental professor Jason M. Colby reads about the love-hate relationship between humanity and Orca whales, and how it mostly became a love-love relationship. University Lutheran Church, 1604 NE 50th St, https://townhallseattle.org, 7:30 pm, $5.Wednesday, June 6: #WeToo: New Visions Of Consent & Reproductive Justice

This open mic asks, “What’s your story about reproductive rights, transgender justice, sex worker rights, abortion access, or being a survivor?” Share a piece of two minutes or less in a comforting, welcoming environment, sponsored in part by the awesome folks at Shout Your Abortion. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.Thursday, June 7: Quiet Until the Thaw Reading

You probably know Alexandra Fuller best for her brilliant memoir Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, and maybe you’ve read Scribbling the Cat. Tonight, Fuller reads from the new paperback edition of her first foray into fiction, Quiet Until the Thaw. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Friday, June 8: A Prenuptial Reading

On Saturday, poets Paige Lewis and Kaveh Akbar will get married. You’re not invited to that. But on Friday night, Lewis and Akbar are hosting a reading to celebrate Lewis’s first chapbook, Reasons to Wake You, and Akbar will read from his celebrated debut Calling a Wolf a Wolf. A number of other fine poets will be taking part in this public celebration of a couple on the cusp of wedded bliss.Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

Saturday, June 9: All Power: Visual Legacies of the Black Panther Party Panel Discussion

To celebrate the half-centennial of Seattle’s Black Panther Party, the Frye is hosting a “panel discussion examining the local impact of the aesthetic legacies of the Black Panther Party with artist, activist, and cultural policy expert Royal Alley-Barnes and King County Councilman Larry Gosset.” These Black Panther Party Events have been a lot of fun, and it’s truly moving to watch as people who were involved with the Party back at the beginning reunite after many decades apart. Frye Art Museum, 704 Terry Ave, 622-9250, http://www.fryemuseum.org/, 2 pm, free.Sunday, June 10: A Ridiculously Large Group Reading

This is a reading by authors Marina Blitshteyn, Dan Hoy, Abraham Smith, and Samantha Zighelboim, along with Seattle treasure Sarah Galvin. What a young, vibrant, exciting bill this is!Open Books, 2414 N. 45th St, 633-0811, http://openpoetrybooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Literary Event of the Week: Planet Funny reading at Elliott Bay Book Company

Although he first made his name as one of Seattle’s two best-known Jeopardy! champions, Ken Jennings has built an interesting post-game-show career. He’s parlayed a record as the winningest Jeopardy! contestant into literary celebrity.

In addition to a line of trivia books for kids, Jennings is the author of a funny memoir about his time as a Jeopardy! champ, Brainiac. Jennings’s charming Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks proved that he wasn’t just a one-hit wonder — that there is, in fact, life after Trebek.

It’s hard to talk about Jennings in a literary context without mentioning that he is very, very good at Twitter. Jennings is, in fact, a hilarious writer who perfected the idea of a zinger that could comfortably fit inside a 140- (and then 280-) character limit. You can’t help but picture him in another life writing zingers for the nightly monologue of someone like Johnny Carson.

With his newest book, Jennings is combining his literary career with his Twitter skills. Subtitled How Comedy Took Over Our Culture, Planet Funny is a history of comedy — going all the way back to Sumeria — and a reckoning for a time in which every asshole with a Twitter handle thinks they’re the host of their own goddamned Daily Show.

Jennings has been talking about the book that would become Planet Funny for years now — it’s been so long since I first heard about it at a party that I thought maybe he’d given up on the thing — but the delay came for the best reason imaginable: he’s been deep in research. Planet Funny is a deeply considered study of where comedy began, and where it’s going.

Tonight, Jennings celebrates Planet Funny’s release with a reading before a hometown crowd at Elliott Bay Book Company. These are the kind of parties that make literary life in Seattle so much fun. Go be a part of it.

The Sunday Post for June 3, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

When a Person of Color Tells Conference Organizers Their Conference Is Too White

In February, award-winning Seattle writer and frequent Seattle Review of Books reviewer Donna Miscolta wrote in her blog about attending the San Miguel Writers’ Conference in Mexico. In addition to the marvelous phrase "in a bat of an eye out of hell" (yes) and praise for San Miguel de Allende's beauty, the post includes an account of overwhelming racial imbalance among conference attendees and outright racism in some of the classes.

This week Miscolta published an update describing the conference organizers' response when she contacted them to suggest a different approach next year. The story is told with her trademark directness and precision — Miscolta isn't afraid of emotion, but she knows how to achieve it in other ways than being loud — which makes it easy to imagine the pragmatism with which she would have approached the conversation. And that makes the response from the organizers all the more stunning. Miscolta's advice to them is dead on and valuable for anyone wondering why good intentions alone haven't brought diversity to their platform.

I got a reply the next day, bubbly and breathless in its defense of their desire and efforts to be diverse. She listed all the brown and black people they had featured as keynote speakers over the years. She assured me that the list of general faculty was even more impressive. She described the Spanish-language element of the conference and its Mexican faculty. She expressed regret that “Unfortunately, we receive very few proposals from African American or Asian writers.”

She ended with, “If you know of writers of color whom you can encourage to apply to teach at our Conference, please do encourage them to apply. We need more applications from people of color.”

Could I possibly let this go?

'Once Upon a Time' and Other Formulaic Folktale Flourishes

I know from personal experience (once upon a time) that there is no end of hyperintelligent, hyperscholarly discussion of how fairy tales and folk tales work, including their iconic opening formulae. My hat’s off to Anthony Madrid for aerating those discussions with just the right mix of irreverance and affectionate astonishment. Seriously, this is so much fun, if you have even five volumes of Andrew Lang or just a dozen books edited by Zipes on your shelf …

Forget “upon a time.” Look at the “once.” That part really is standard from the beginning, and not only in English. Just this past weekend, I paged through fifteen volumes of the Pantheon Fairy Tale and Folklore Library, and I’m here to tell you: The word once is in the first sentence of almost every single folktale every recorded, from China to Peru. There is some law of physics involved.

Hazardous Cravings

Men feel shame when their bodies don’t fit the social standard, they swallow down those cruel, mocking voices just like women, they destroy their bodies from the inside to make the outside “fit” — all complicated by the expectation that men will be worthy and loveable no matter what their shape (and other myths of masculinity). Alex McElroy tells that story with devastating directness in the setting of a teen job at a Dairy Queen.

I was terrified that the pills would work. Taking one would become taking them regularly, then obsessively, until they snuffed my heart like fingers pinching a flame. But I couldn’t confess this to Boots. Perhaps we weren’t, as I’d liked to believe, enacting some vulnerable version of masculinity but applying its worst expectations — sacrificing our bodies, refusing to care for ourselves — to a traditionally feminine project: becoming thinner. Because as open as we were with each other, we nevertheless refused to acknowledge the damage we caused to ourselves. We couldn’t. We lacked the language to see our sickness as sickness. He could not be “anorexic,” just as I could not be “bulimic.” For men, those words were locked houses.

Icelandic fiction: a family affair

“Any resemblance is purely coincidental” doesn’t hold much water when you live on an island so small that the population approaches dating with a genealogical pre-check. Fríða Ísberg on the peculiar challenges of being a writer (or, more exactly, the family and friends of a writer) in Iceland.

Autobiographical fiction has become widely popular across Scandinavia, and Iceland has proven to be no exception. But Iceland, with its small population, poses unusual ethical problems concerning what one can, and should, write: how does one balance the reputation of real characters against the liberty of the author? And what are the consequences in a country the size of Iceland when a writer, perhaps following the model of Karl Ove Knausgaard, exposes those around them?

Traumatic License: An Oral History of Action Park

You can go see Action Point, the oddball movie about the amusement park geared toward allowing its guests to do maximum bodily harm to themselves, or you can read this amazing oral history of the real park on which the film is loosely based. Owned by Eugene Mulvihill, Action Park was open in Vernon, New Jersey for more than a decade starting in 1983. I mean, this park had rides that put you in the water with snakes and snapping turtles, rides that could break your face, rides that could strip the top layer of skin from your entire body. I can barely choose a quote from this, it’s astonishingly, gloriously ridiculous from start to finish.

Al Rescinio (Guest): It wasn’t like you were armored going down this thing. You’re wearing a T-shirt and bathing suit or shorts. You didn’t know how unstable these little carts are the first time you go on them.

Thomas Flynn (First Aid): The primary ingredient in those tracks was asbestos, by the way.

DeSaye: People would bounce off. That’s why we called them Gumbys. Down in first aid, at the end of the night, you’d be having pizza and inevitably someone would come in looking like they had a giant burn from head to toe.

Benneyan: It was the Action Park tattoo.

Whatcha Reading, Lucy Bellwood?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Lucy Bellwood is a (best title ever coming): professional Adventure Cartoonist. She's based in Portland. Her latest book 100 Demon Dialogues (full disclosure: I was a Kickstarter backer, and even got one of the adorably awesome Demon plushies) is great — funny, interesting, empathetic, and honest about the process of making art. Her previous book, Baggywrinkles, is a fun, fascinating, and educational comic about her experience working on square-rigged ships (really!). She's appearing twice in the Seattle area in the coming week: 7:00pm Friday, June 8th, at Brick & Mortar Books in Redmond Town Center, and 2:00pm on Saturday, June 9th, at Outsider Comics and Geek Boutique. It's worth your time to go see Lucy in person!

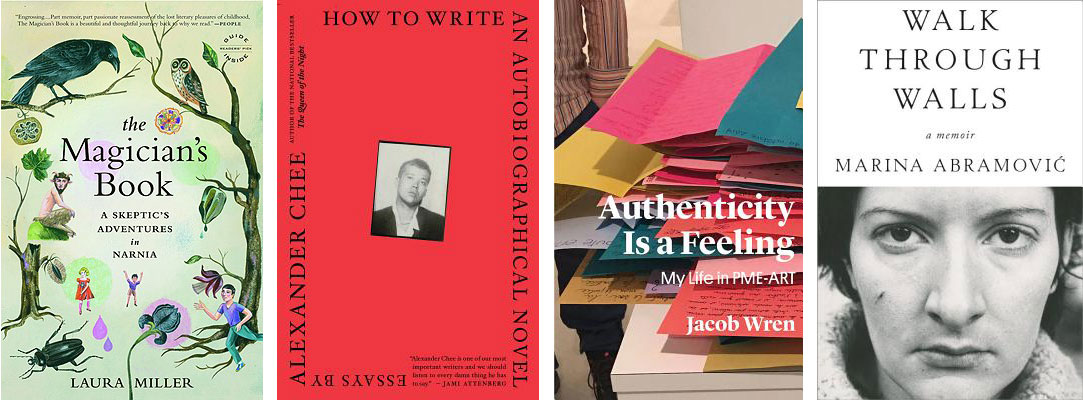

What are you reading now?

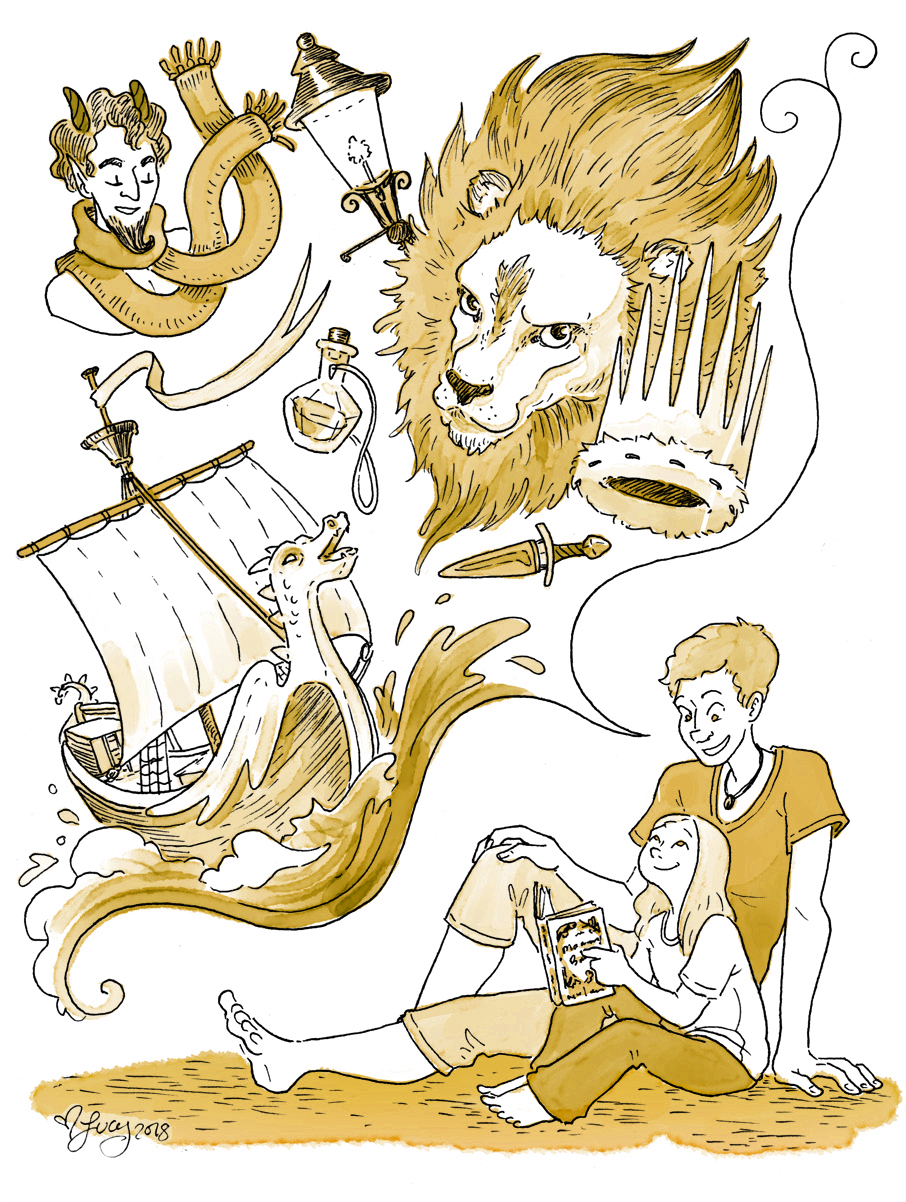

Laura Miller’s The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia. I fell in love with the beautiful, clothbound Narnia books in our house when I was very young. My mother used to read them to me before bed. (I’m even named, in part, after Lucy Pevensie.) Like Miller, I didn't encounter the books’ Christian themes until I was a teenager, and felt deeply betrayed once I had. Returning to Narnia through Miller’s criticism is rekindling all the things I loved about the series as a child, but with an insight and breadth I couldn’t lay my hands on in high school. There’s a compassion and curiosity to her analysis of Lewis’s life and influences that I really love. This isn’t a map of how Christian themes permeate the text, but rather a broadening web of literary theory, personal anecdotes, and biographical detail. I’m so, so glad I picked it up.

What did you read last?

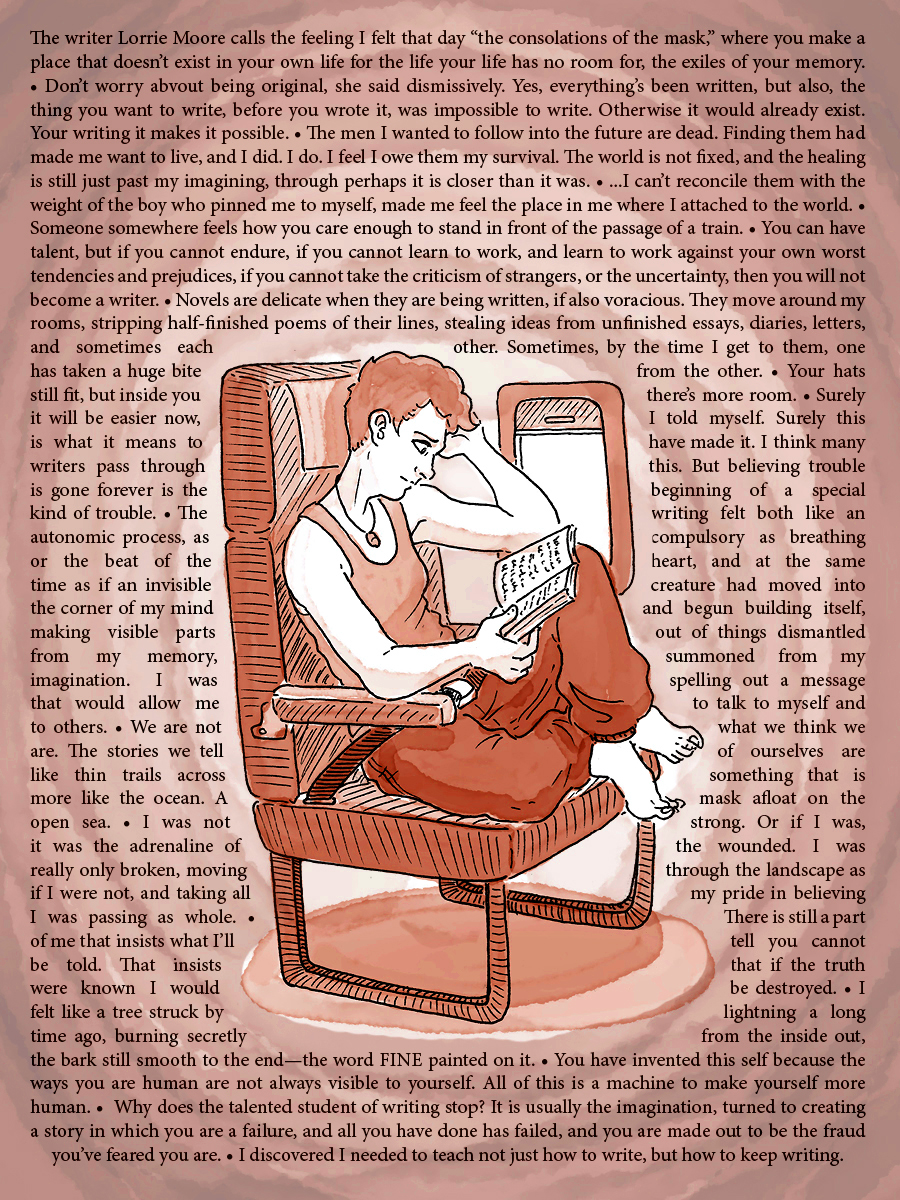

Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. I tore through it in one sitting on a flight home from Toronto, in tears maybe 70% of the time. I loved reading Chee’s thoughts on money and writing in Scratch, which is definitely one of the best collections I’ve read this year, but I wasn’t prepared for the force of reading so many of his pieces back to back. He’s a fabulous writer — vulnerable, insightful, and cripplingly precise. His articulation of the creative process—particularly the interplay of trauma, identity, and discovery is so accurate. It’s a very distinct pleasure to see how writers approach the same themes through different biographical lenses over time, and this collection is perfect for that.

What are you reading next?

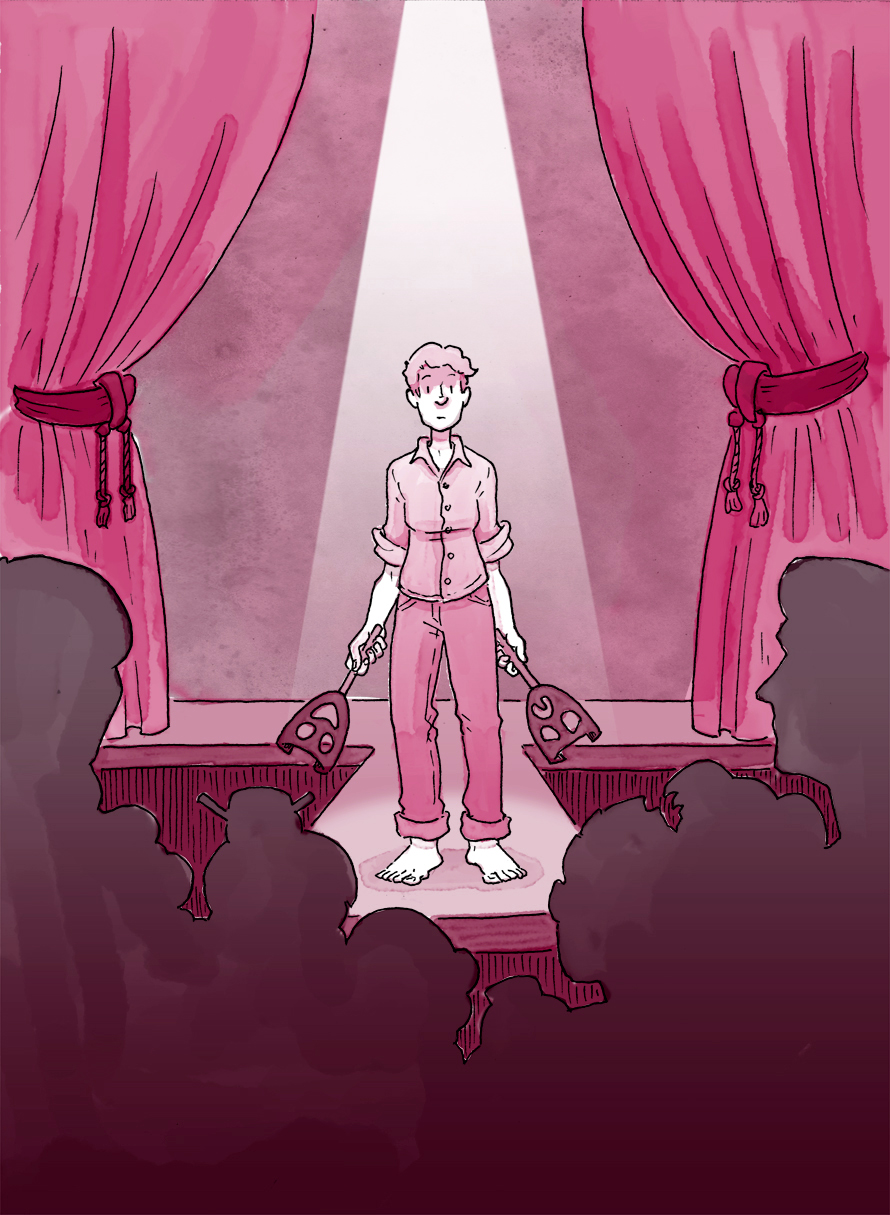

Authenticity is a Feeling by Jacob Wren, who’s the co-artistic director of an experimental theater group I’d never heard of called PME-ART. I snatched it off the Staff Picks shelf at Type Books in Toronto because it claims to investigate the challenge of “being yourself in a performance situation.” As an autobiographical cartoonist with a penchant for oversharing and a background in theater, this is something I think about a lot. A huge portion of my creative and professional life takes place online. As I branch into doing more facilitation and public speaking I’m mulling over how we can ever present complete, truthful versions of ourselves to an audience. (This line of thinking really kicked into high gear after I saw In & Of Itself, an indescribable show by Derek DelGaudio, last October. It’s closing this summer. If you haven’t seen it I suggest you check it out.) I’m also guessing this is going to pair really well with Marina Abramović’s memoir, Walk Through Walls, which has been in my to read stack for a while.

May's Post-It Note art from Instagram

Over on our Instagram page, we're posting a weekly installation from Clare Johnson's Post-It Note Project, a long-running daily project. Here's her wrap-up and statement from May's posts.

May's theme: Film Festival

Every May I’m swept up in the Seattle International Film Festival. Life gets crammed with movies, calendar a strange logic puzzle of screenings around other screenings around work, friends, deadlines. All my days are overfull, and at the same time it slows me down, I walk extra stretches of city between cinemas and studio and home, wait meditatively in long lines, meet with friends or chat gently with strangers, or mostly on my own, pausing, just me and someone else’s giant art, filling my whole field of vision. The films in these post-its aren’t all from SIFF, but they’re things I got caught up in, found myself thinking about later as I went to bed, couldn’t quite shake. Maleficent finally celebrated the one kind of princess-movie character I loved — the female villain. Maleficent was why I ever watched Sleeping Beauty, a favorite character, totally captivating, I practiced drawing the curves of her fancy horns. I was always easily scared, never wanted meanness to win — but little kid me knew these evil ladies were undeniably the main attraction, even if Disney didn’t understand, wouldn’t give them real stories or let powerful women take care of each other. But then suddenly for a moment it did. Driving home late from the theater, I sang along happily to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs on the radio. I saw The Queen of Ireland, a documentary about drag queen and accidental activist Panti Bliss, at SIFF a couple years ago; the post-it is a paltry reminder of her famous speech in all its plainspoken nuanced brilliance. Seeing Hidden Figures on the big screen was similarly glorious (also the book! read the book!!), except OH MY GOD, that laughter. How grotesquely, misguidedly comfortable are we — to laugh at such a moment, to think scenes of a woman of color struggling to make it to the segregated bathroom are meant as entertainment. The last one is Blue Is the Warmest Color. I don’t have anything else to add about that.

The Help Desk: Does whatever a spider can

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

Angela, Allentown

Dear Angela,

No I have not read it, thank you for the recommendation! Have you read this interesting article on scientists teaching a spider named Kim to jump on command? While I applaud their efforts, I’ve been training up a team of spiders for the amateur circus circuit this summer (coming to a truck stop near you!), so I’m not that impressed that they taught one to jump. It’s true spiders only eat about once a week but those thirsty motherfuckers will do backflips for a strong lime rickey just about every night. And just try fitting them in spandex singlets – Jesus Christ. If that isn’t a science I don’t know what is.

Kisses,

Cienna

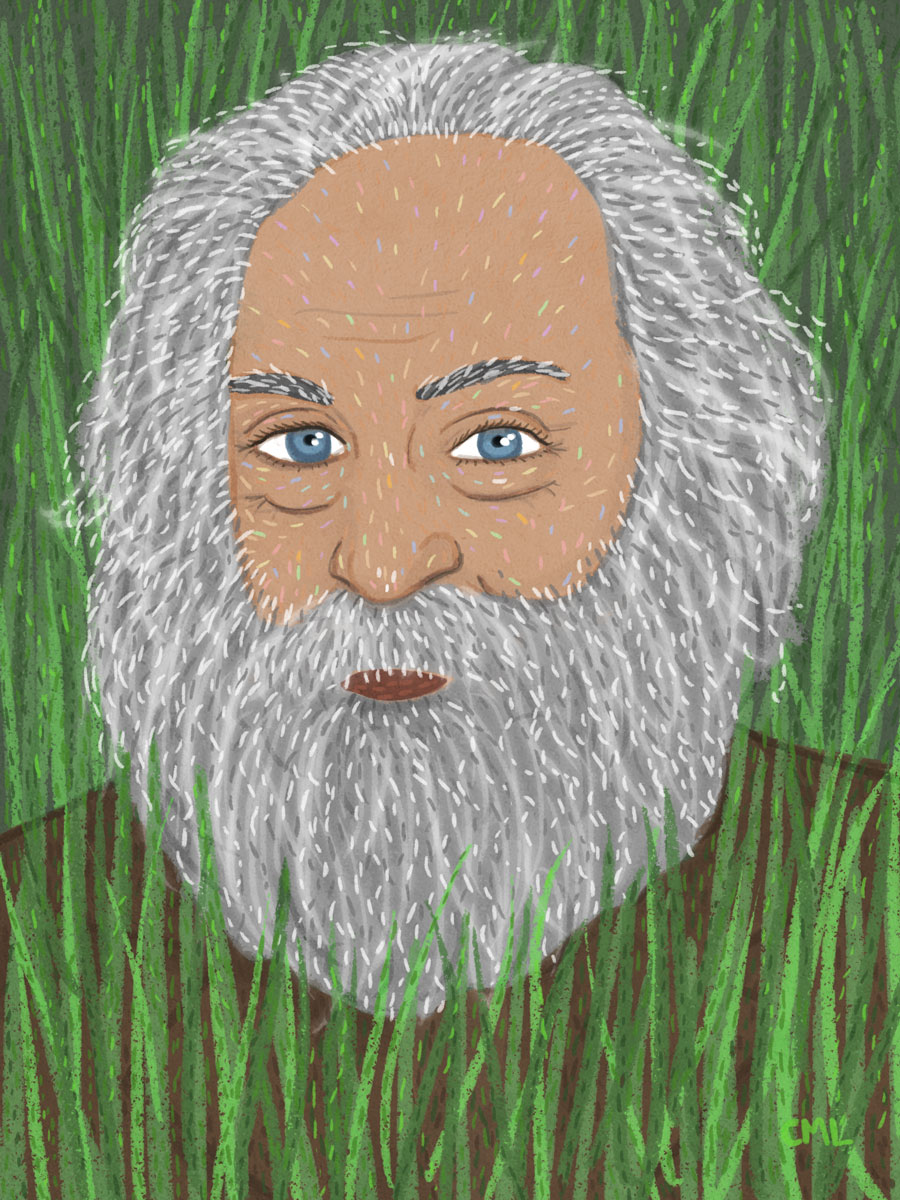

Portrait Gallery: Walt Whitman

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Today is Walt Whitman's 199th birthday. Learn more about this seminal American poet and essayist and spend some time with his works: https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/walt-whitman

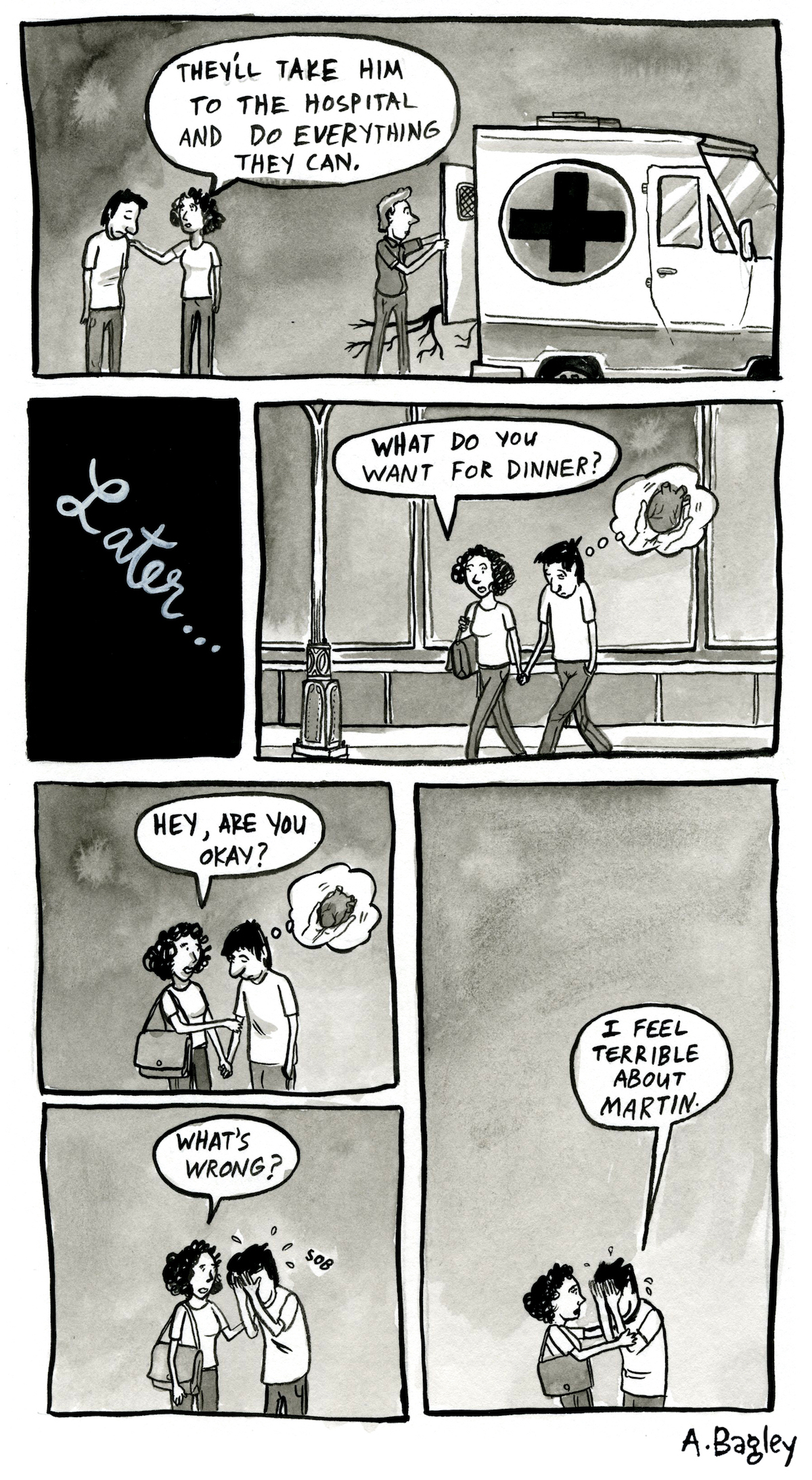

Good grief

Published May 31, 2018, at 12:00pm

Grief memoirs defy our expectations, says Emery Ross, and teach us about much more than loss.

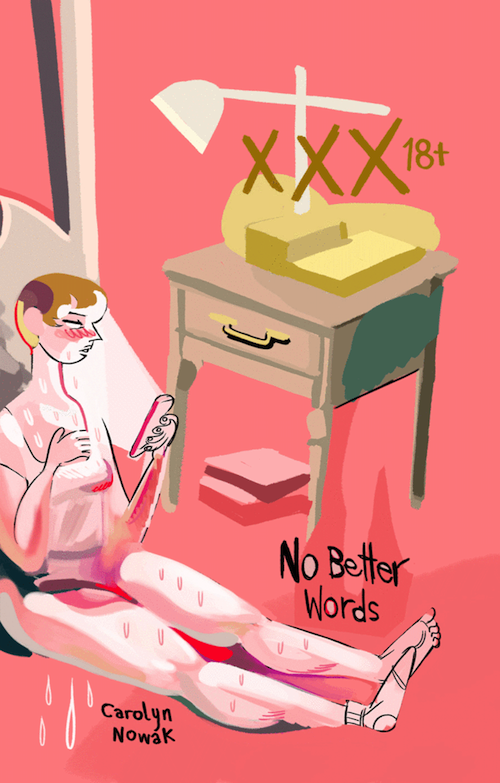

Thursday Comics Hangover: Spring has sprung

No Better Words is not a new comic. It’s not even a comic that I encountered this week. I bought Carolyn Nowak’s short poetry-and-lust comic a couple months ago, at the Strand in New York City, and I just happened to pick it up and read it this past week when it caught my eye.

Good lord.

It just so happens that No Better Words is the perfect comic to read at the time when spring is teetering over into the edge of a hot and sticky summer, when everything is blooming and singing and glowing from the inside out.

The story is simple: a young woman hails an Uber, and goes to a house party that has just ended. She has one goal in mind: a young man she can’t get out of her head. She finds him, and she throws herself at him. She’s there, put simply, to fuck.

On her way to the party, she concocts several metaphors to explain the sheer physical longing she feels — he’s a cold planet, but “cold like the other side of your pillow.” Or maybe he’s a maze of cloth, rustling in the breeze. Or maybe the metaphors are just a pretense her brain creates to distract her from the idea that she just really wants to get it on.

It's a rare pleasure to find a comic this purely horny. Nowak has colored No Better Words in pastel pinks and purples, and the subtle blush on the young woman’s cheeks say more than any of her hormone-fueled metaphors ever could.

If you’re young, or if you ever spent your youth in beer-soaked ragers hoping someone would come along and adore you the way you wanted to be adored, No Better Words is a fairy tale meant just for you. And if you look past the eager lips and the gauzy, semi-stupid stares, you’ll likely recognize the tragedy just nipping at the heels of all the yearning. It’s sexy because of that heartbreak, that emotional risk, not in spite of it.

The Fountainhead to fail upward until it lands in a cinema near you

A whole lot of people sent me the news yesterday that Zack Snyder — director of maybe three of the worst ten movies I’ve ever seen — is allegedly working on an adaptation of Ayn Rand’s novel The Fountainhead.

Let’s be clear: Zack Snyder is a terrible director, but he’s an even worse writer. The best thing you could say about his adaptation of Watchmen was that it occasionally did a good job of literally throwing comic book panels up on the screen. His DC superhero films are absolute messes, with nothing to recommend. And Sucker Punch is a misogynistic turd of a movie that I actively regret watching.

But while we’re talking honestly, Ayn Rand is a million times worse than Zack Snyder will ever be. Her books are a cancer on society; they’ve convinced a small army of young white men that they deserve every ounce of privilege they were born into. Her books created two of the worst political figures of our time — Paul Ryan and Rand Paul. And the legacy of her writing, if left unchecked, will result in nothing less than the complete destruction of society as we know it.

So, no. I’m not looking forward to this movie.

But it’s worse than that. Here’s a dirty little secret about The Fountainhead: it’s a terrible book. The Fountainhead opens with a graphic scene of sexual assault perpetrated by the “hero” of the book, and the narrative POV never once questions that hero’s intentions.

The plot, in its most basic terms, is about a young man who is always right about everything. Throughout the book, he deals with annoying people who are always wrong. Eventually, everyone realizes that he was right about everything, and then they give him everything he ever wanted. The end. There’s no conflict, no growth, no real drama to The Fountainhead.

If you don’t believe me, get a load of this climactic scene from the 1949 Fountainhead adaptation, in which the hero (Gary Cooper) explains patiently why he is a maker and everyone else in the world is a taker:

Of course, Snyder doesn’t really understand conflict, either. (I dare you to explain Lex Luthor’s plan in Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice to me in 25 words or less.) So what we’ll likely see is a collection of slow-motion scenes and a single, lovingly shot explosion, strung together with a passel of monologues. What we’ll get is an adaptation of a book written by an asshole, adapted by an asshole, starring an asshole, for an audience of assholes.

All that said, this movie will probably do well at the box office. To tweak a cliche just a little bit, nobody in the year of our lord 2018 ever went broke underestimating the rampant assholery of the American public.

Susan Rich's poems are beautiful music

Susan Rich’s poems thrum with a rhythm all their own. Read any of our May Poet in Residence’s poems and you’ll likely be absorbed in the rhythm of the thing — dense internal rhythms, tricky beats in single lines, sentences that shouldn’t exist but somehow manage to thrive.

I don’t know, for instance, how Rich makes a line like “we accordioned together vaudeville-style” work. But in “Self Portrait with Abortion and Bee Sting,” it not only scans but it feels essential — like the only words that could logically fit there. Her poems are full of those impossible lines — if I ever wrote something as beautiful about an earthworm as “Pink hermaphrodite of the jiggling zither,” I would probably retire in triumph.

“Rhythm is super-important to me,” Rich confirms over the phone, but she sounds unsure about exactly why it takes on such an importance for her. “I studied scansion. On a good day, I can tell you iambic pentameter from iambic hexameter.”

But she’s not driven solely by beats. When writing a poem, Rich says, “sound is important, and the playfulness of language is paramount.” She calls herself “very interested in the sounds of vowels and the sounds of certain consonants,” and she has lately been admiring the poems of Frank Gaspar, saying that from the beginning of his book Late Rapturous, “it was clear there was a lot of sounds” packed inside. “The ‘o’ was everywhere,” she says.

“I started writing when I was young,” Rich says. “I loved reading and writing, all through elementary school.” But when she attended the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, she says, calamity struck in the form of “old white poets who went out of their way to tell me I wasn’t a poet.” Rich still sounds offended when she thinks of those men, who she describes as “pretty famous poets.” Because of their criticism, she didn’t write poetry for a decade. Eventually, after a stint in Niger through the Peace Corps, Rich took up painting – mostly “moldy oranges and grapefruits and shimmery shiny fruits” — and then returned to poetry.

More than just a writer and a teacher of poetry, Rich is a voracious reader of poetry, too. “I try to read everything. There’s amazing poets coming out all time,” she says, and she seems to fall in love frequently. She’s breathless when she talks about the relentless rhyming in Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” for instance. “That ‘master’ and ‘disaster,’” she says, “wouldn’t hit you on the head when you read it a second or third time,” but she calls it “the rhyme that keeps coming." Other poets she admires include Adrienne Rich (“no relation,” she quickly adds) and Ellen Bass and Denise Levertov.

In Rich’s fantasies, she’d be a great singer, and that aspiration to musical talent does come through in the writing and the reading of the poems. That said, “I think rhythm in poetry is different” from music. “I’ve been told I don’t read the poem the same way each time,” Rich says, and she sounds happy about that. “I don’t want to sing my poems, I don’t want to do the terrible poet-voice. I love reading.”

When she writes, Rich says, “I have no interest in being obscure.” But she’s not a narrative poet, either. She keeps a distance from her subject: “my point in poetry is usually hovering above.” Sometimes, she feels uncategorizable. “They don’t know where to put me. They say I don’t fit in a Northwest poetry tradition.”

“I suppose the element that keeps me from being a narrative poet is the surreal,” but she quickly corrects herself: “I don’t claim to be a surrealist.” Then, more thoughtfully: “I’m not sure there are even surrealists walking around. I’m not sure anyone ever wanted to be claimed by that title.”

And sometimes surrealism is nothing more than an accurate reflection of reality. “I have a poem that comes from a news story of a 99 year old woman waking up one morning and finding a kinkajou — an exotic animal from Brazil — sleeping on her chest.” Rich says that image “grabbed my imagination and I had to imagine what would it be like to be a 99 year old woman, husband dead, to find this warm thing resting on her chest.”

The resulting poem is gorgeous, with the kinkajou — "this feral thing she’s never known before" — resting on the elderly widow “like an unexamined question.” Rich found the heart in the news story, and she reported the loneliness and the excitement back to her readers.

Rich is working to complete a new book of poetry that centers on “a relationship I had when I was in my late twenties that ended disastrously in an abortion. That’s as baldly as I can put it.” This summer, she’s going to work to finally get the poems edited and ordered and “off my computer.” Rich sounds a little scared of the new book, but entirely confident that it’s the book that she needs to be writing right now. “Poetry is the way I make sense of the world,” she says.

Come out June 7 for the release of Walk Tall Y'all

Hom's art belies the emotional weight he brings to chronicling the changes in Seattle's Beacon Hill neighborhood, through the eyes of Wallace, who's seeing the city after almost half a century away. What Wallace experiences is more than losing familiar family homes to condos — he's coming back to a Seattle whose economic, racial, and cultural fabric has essentially changed. It's a shock of several kinds, and Hom's clean lines and gentle but direct storytelling are the perfect vehicle.

Sponsors like Dale Hom not only bring great events and new releases to your attention, they make the Seattle Review of Books possible. Did you know you could sponsor us, as well? If you have a book, event, or opportunity you’d like to get in front of our readers, find out more, or check available dates and reserve a spot. Only a couple of dates left in our currently available slots — grab one before they're gone.

It's summer, so it's time for Book Bingo

Every summer, the Seattle Public Library and Seattle Arts and Lectures host a game of Book Bingo. The rundown, if you're new to town: fill a single row of the official bingo card (or, if you're ambitious, black out an entire card) by September 3rd and be entered to win prizes including gift certificates to local indie bookstores or a whole library of Seattle Arts and Lectures authors and tickets to the SAL 2018 season.

This year's card — which you can download here as a PDF — features intriguing squares like "suggested by a young person," "your best friend's favorite book," and "finish a book you started and put down."

If you're feeling ambitious, you can report your progress on social media using the hashtag #BookBingoNW2018. It's already hopping over on Twitter. And if you need help choosing books to complete your bingo card, you can ask a real, live librarian to email you a list of personalized suggestions through Seattle Public Library's Your Next Five program.

Self Portrait With Abortion and Bee Sting

Last night while watering the garden,

I mistakenly elbowed a yellow jacket

or perhaps it was a carpenter beecasually bathing in a galaxy

of purple astor. And then, as if

taking the Circle Train home,

we accordioned together vaudeville-style —our physical margins shaken

by the surface of bright lies.

And through the torn sleeve

of my sweater, I felt the stingerinsert until you stumbled, slow-motion,

into the flowerpot; inert like a lover

who has overexerted himself,

then lies down in the gold huskof a late July night.

Now all that remains of us is a raised scar,

burning like a silver dollar —

swiftly seen-to with wet tea bags and copper pennies —the way we tried to exorcise the toxins

from our lives: a blue basin next to the crib

of a sick infant or a vacuum cleaner hung,

then ignored, in the guest room closet.When you left, I didn’t recognize myself in the drapes.

I took down all the mirrors

from the walls, subsisting on huckleberries

and the machinery of my heartwhich came as a continuous surprise —

the new knowledge that

my body could outlast death —

could heal this deep, sharp sting.

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from May 28th - June 3rd

Monday, May 28: Northwest Folklife Festival

Today at Folklife, you can find all sorts of music, crafts, and food. Storytelling events include a story slam at 11 am, a Spanish-language reading from Seattle Escribe at 3:15 pm, and discussions of food and culture all day long. Seattle Center, 11 am, $10 suggested donation.Tuesday, May 29: Aki Kurose Poetry Slam

Every year, the students of Aki Kurose Middle School read their poetry at Third Place Books Seward Park. This sounds like a great way to be inspired by a new generation of young writers. Come show your support. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, May 30: Writers in the Schools Reading

It’s a week for young writers! Students who participate in Seattle Arts and Lectures’s excellent Writers in the Schools program will read new work created in the program at this event. Meet tomorrow’s great new writers today! Students will read all sorts of original work: poetry, fiction, and memoir. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.Thursday, May 31: Elements of a Bystander Reading

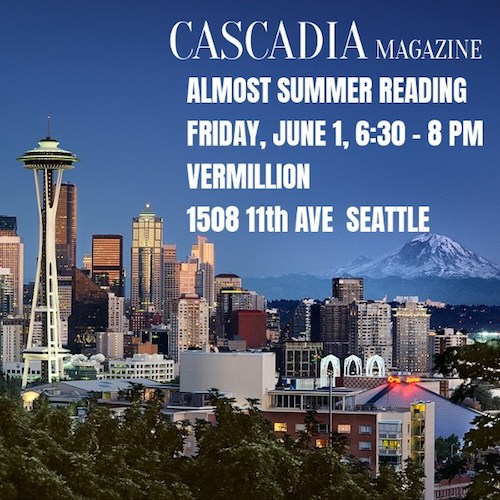

Seattle writer Juan Carlos Reyes celebrates the launch of a short story collection titled Elements of a Bystander. He’s joined by Seattle author and publisher Amber Nelson, who has a book out soon titled The Sexiest Man Alive. They’ll be joined by Jason McCall, who is the author of a book of poetry titled Two-Face God. Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, http://vermillionseattle.com, 7 pm, free.Friday, June 1: Cascadia Magazine Party

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, http://vermillionseattle.com, 6 pm, free.

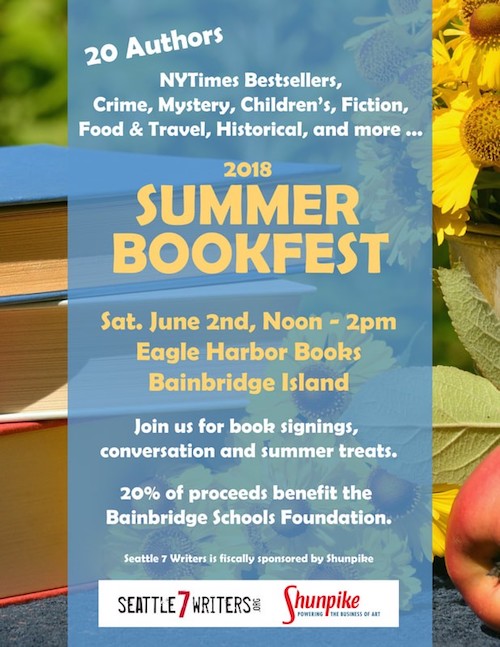

Saturday, June 2: Summer Bookfest

Eagle Harbor Book Company hosts a murderer’s row of local talent in a two-hour book festival that benefits the Bainbridge School Foundation. Authors include Elizabeth George, Kathleen Alcala, Anastacia-Reneé, Carol Cassella, Waverly Fitzgerald, Jarret Middleton, Donna Miscolta, Claudia Rowe, and Anca L. Szilágyi. This is definitely worth the trip across the water. Eagle Harbor Book Company, 157 Winslow Way E, 842-5332, https://www.eagleharborbooks.com/, noon, free.Sunday, June 3: Manuscript Class Dismissed

For a full year, students have taken Theo Pauline Nestor’s Hugo House Yearlong Manuscript Class, which helped them shepherd a memoir from concept to completion. This afternoon, the students will read from their work and maybe talk a little bit about the process of working with a close-knit group of people for such a long time on such an intimate type of writing. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 3 pm, free.Literary Event of the Week: Cascadia Mag's Almost Summer Reading

Even though there are seemingly fewer magazines and media outlets in Seattle right now than at any point in recent memory, it is surprisingly difficult to get a publication off the ground. It takes a lot of hard work to remind people to come to a website on a regular basis — hey, thanks, reader! — and Facebook won't allow publishers to find a new audience unless they pay a disgusting amount of extortion money.

That's why I admire Cascadia Magazine for launching a publication at a time when other media outlets are dashing themselves against the rocky shore of public indifference. Bolstered by a daily news email and featuring a voracious mixture of fiction and non-fiction, Cascadia has worked hard to establish a place for itself in the landscape.

Cascadia is a fine balance of a publication: it's smart but not snarky, engaging but not needy, and opinionated without being smug. Billed as "exploring ideas and cultures from the bioregion," Cascadia features author interviews, true explorations of homelessness and equitable pot farming, fiction from writers like Donna Miscolta, and poetry from writers like EJ Koh. In case you can't tell from that list, they are not screwing around at Cascadia.

On Friday, the magazine hosts its first meatspace get-together, in the form of a reading program at Vermillion, the art bar on Capitol Hill that is as close as Seattle gets to a literary hangout. Here's Cascadia's description of the readers:

You’ll hear Donna Miscolta and Anca Szilágyi read new fiction, listen to poetry from Michael Schmeltzer and Montreux Rotholtz, view photographs by Daniel Hawkins, and hear journalists Niki Stojnic and Matt Stangel talk about issues that matter to people living in the Cascadia bioregion.

All that for the low, low cost of free? Why wouldn't you show up for this? At the very least, it's important to show your support for an organization that's happily dumb enough to try to make it in the current media scene. If you find Cascadia publisher Andrew Engelson at the event, buy him a beer and toast his impeccable taste in windmill-tilting. We need more people like him.

The Sunday Post for May 27, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

A Lexicographer’s Guide to Real Words

I agree with Kory Stamper here (“I agree with Kory Stamper” is almost a tautology): unlike the news, there are no fake words. Though I might advocate for declaring some words fake, like “innovation” and “disruptive” and the use of “impacted” to mean “had an effect on.” Irregardless, this is an absolutely splendid opportunity to do that thing we all used to do on the Internet and fall down the rabbithole of clicking all the links in this post that lead to other posts in Stamper’s blog, and then clicking all the links in those posts, and then it’s almost dinnertime and you don’t have your column done but who cares? Kory Stamper!

And even if a word is illogical or stupid, so what? You know how many completely unremarkable words arose from a stupid misreading? You use "cherry" and "apron" just fine, even though "cherry" came about because some 14th-century doofus thought the Anglo-French "cherise" was plural (it wasn't), and "apron" came about because court clerk read "a napron" as "an apron" and rendered it as such, and then future readers thought, "Oh, man, the clerk to Edward III says it's 'apron,' I better get in line," even though that same clerk used "napron" later in the Household Ordinances, and here we are.

What's Going On in Your Child's Brain When You Read Them a Story?

This short piece by Anya Kamenetz is very cool. It offers some real, though preliminary, scientific evidence that reading to your kids is better than plopping them in front of a television set. And it also offers a lens into a part of the brain — the default mode network — that scientific researchers (those romantics!) call “the seat of the soul.” It’s the bit of your mind that’s absolutely farthest from the buzz of social media, the bit associated with self-reflection, daydreaming, and spontaneous thought. Knowing how to cultivate that early and keep it talking to the rest of our overstimulated brains seems like a potentially society-saving discovery.

When children could see illustrations, language-network activity dropped a bit compared to the audio condition. Instead of only paying attention to the words, Hutton says, the children's understanding of the story was "scaffolded" by having the images as clues.

"Give them a picture and they have a cookie to work with," he explains. "With animation it's all dumped on them all at once and they don't have to do any of the work."

Most importantly, in the illustrated book condition, researchers saw increased connectivity between — and among — all the networks they were looking at: visual perception, imagery, default mode and language.

Tech Billionaires Are Building Their Utopias Without Asking Us

The dream of outer space is an expansive dream, big enough to hold intergalactic battles, exploration of the unbearably unknown, and deeply human interactions with deeply alien cultures. Space is The Martian and Star Trek and Ursula K. Le Guin and Sally Ride separated by light years of beliefs and hopes and fears, then tessered back so close they’re almost touching.

The dream of space is expansive, and it’s almost always a dream of something little overcoming something big. It’s not a dream of the richest men on earth claiming outer space as their own personal utopia and throwing up walls of money and power around it. S. A. Applin wonders whether Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk know they’re not, and can’t ever be, the heroes of the space story they’re writing for the rest of us.

We all carry visions of our own utopias, working towards betterment of self, community, or dreaming of an escape. It’s how we focus intent for what we want. The game changes though, when people who have resources can suddenly begin to realize those changes in their Utopian visions, and those visions being realized may begin to conflict with others who have less money and power to realize theirs.

Whatcha Reading, Levi Stahl?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Levi Stahl is associate marketing director at the University of Chicago Press, where he's worked since 1999. He is also the editor of The Getaway Car: A Donald E. Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany. He's a great follow on Twitter, where he often posts passages that catch his eye, from whatever he's reading. This complete delight stands out, on a website full of so much undelight.

What are you reading now?

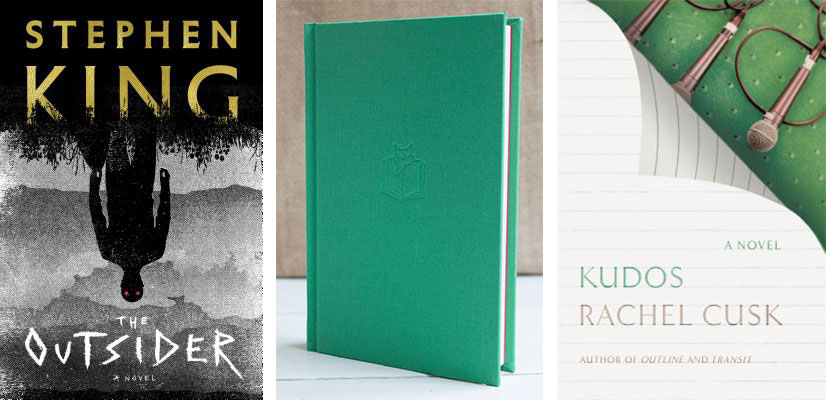

Stephen King's The Outsider. I will confess to being unsound on the topic of King: he was too important a part of my early teen reading life for me to ever be able to make a fully rational, objective assessment. I can see the flaws: his prose, especially in recent years, can be too casual; his humor almost all falls flat (he has what I tend to think of as a Boomer belief that irreverence is interesting and funny on its face); he seems never to have had the benefit of a skilled editor who could help him tighten his work. But when the books work (such as, off the top of my head, The Stand, Night Shift, The Shining, It, Pet Sematary, Lisey's Story), they lock in and pull you along with an incredible narrative power, combining an urgent desire to simply find out what happens next with an equally strong desire to see the characters come through it somehow. And if you're reading the right book late at night, he can still legit terrify you.

All of which is preamble to: after a few books that I felt were misfires, The Outsider, 200 pages in, is a remarkable return to the heights. It could all fall apart in the last two-thirds, but, lord, right now I am having trouble not scrapping my workday and going back to it.

What did you read last?

Adrian Bell's The Cherry Tree. First published in 1932 and republished recently by Slightly Foxed, a small UK-based publisher that specializes in what I call (with no intention of disparagement) minor English memoirs, in beautiful little cloth-bound limited editions, it's the third part in a trilogy about Bell's experience becoming a farmer in Suffolk in the 1920s. Bell wasn't raised to the work — he had a privileged urban upbringing and surprised his family when he announced after leaving school that he was going to go work on a farm. But he took to the work as if fated, and his three books about learning to farm and making his home in a small village offer a wonderful combination of period detail, entertaining stories, and beautfully understated nature writing. As a kid who grew up in an American farm family at a very different time and has acquired a deep love of the English countryside and the accompanying nature writing tradition, Bell's books couldn't be a better fit for me. For those coming newly to his work, I actually think reading them out of order is best: the middle volume, Silver Ley, is the most interesting and welcoming; once he's hooked you there, you can move on to Corduroy and The Cherry Tree.

What are you reading next?

Well, if Stephen King can sustain me until Tuesday — which, let's be honest, is doubtful with a long weekend coming — I'll turn with great anticipation to a book that's being published that day: Kudos, the final volume in the loose trilogy that English novelist Rachel Cusk began with Outline and Transit. I only started reading Cusk last year, and when I drew up a list of my twenty favorite writers on Twitter the other day, she easily took a space. All of Cusk's novels offer insight after insight into human behavior, often phrased with aphoristic precision. In this most recent group, however, she's taken a noticeable step forward — and what makes them stand out is that they're fundamentally novels about listening to other people tell their stories. There's an "I," about whom we do learn a fair amount, but her life is primarily there as the stage on which people around her talk about their lives, in a fashion that nears oral history at times. Yet it's oral history presented through a narrative perspective that quietly offers judgment — people damn themselves with their own solipsistic words, and Cusk, without being so ham-handed as to point it out, nonetheless makes sure we don't miss it, and in seeing it, find ourselves thinking about our own failings. "How often people betrayed themselves by what they noticed in others," her protagonist thinks in Transit. It's a line I've not been able to forget. I cannot wait to read this book.