You need to visit the new Folio space as soon as possible

Okay, so here's how you get to the new location of Folio: when you're facing the Pike Place Market sign, walk straight toward the fish-throwers. Then, take a left. You'll see some stairs up. Take them. You'll pass the offices for the newsstand and the doughnut stand. At the top of the stairs, you'll run into Folio. The Market is pretty picky about who gets to put signs where and why, and so a lot of people at the party to celebrate Folio's grand re-opening last night were grumbling about getting lost trying to find the place.

But oh boy is it worth the hunt. The new Folio space is gorgeous. There's a big hall with skylights and a great sound system that will be perfect for readings, and then there are two stately library rooms with comfortable seating and stunning views of the Sound. (If you look directly down from the windows, you'll see the world-famous Gum Wall in Post Alley.) Everywhere, there are books: displays of oddly shaped books; selections from Madeline DeFrees's library, which was donated to Folio; free books for the taking on a cart outside the front door.

Though it was located right downtown, Folio's first location in the belly of the downtown YMCA always felt somehow removed from the city. The new location places it right in the heart of Seattle. This is a venue that can remind you why you live in this town. This is a place you'll want to be.

Thursday Comics Hangover: The circle and the rectangle

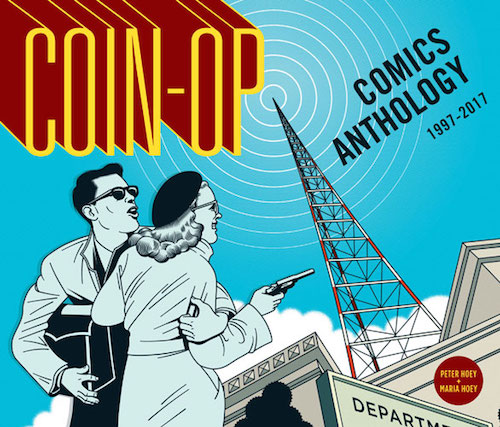

I've written a few times before about my love for the comics magazine Coin-Op, which is written and drawn and colored and designed and everything-else-d by brother-sister cartooning team Peter and Maria Hoey.

You might have had a hard time tracking down an issue of Coin-Op the last few times I wrote about it; the series was only available at a few indie shops or at special occasions attended by the Hoeys, like the Short Run Festival. Now, though, you're out of excuses: you can pick up or order a hefty collection of the Hoey siblings' comics at any bookstore in the country. Published by Top Shelf Productions, Coin-Op Comics Anthology: 1997 - 2017 is a sharp-looking hardcover collection of the first five Coin-Op books, as well as earlier Hoey comics that appeared in places like Blab! Magazine.

Coin-Op comics are fundamentally built out of two distinct shapes. First is the squat rectangle of the page. All the Hoeys' strips are laid out in horizontal format, giving each page a sprawling sense for those who are accustomed to the vertical orientation of most modern comics.

The second, and maybe most important, shape is the circle. (I'm hardly the first person to notice this: "The characteristic icon of Coin-Op is the perfect circle," writes Josh O'Neill in the introduction to the book.)The Hoeys evoke perfectly rendered circles in almost all their work, from a crisp white tabletop to the chaos of a river flooding a nondescript office in overlapping circular panels. Their characters run in circles. In some instances, their heads are perfect circles. The moon hangs in the sky like a shiny quarter. A man examines a diamond ring.

All of the comics in Coin-Op riff on variations of those two shapes: the broad expanse of a rectangle and the unending loops of a circle. A movie screen and a spinning jazz record. The Hoeys are history buffs, drawing strips that riff on Vertigo and the life of the director of Rebel Without a Cause. Other strips discuss the life and legacy of jazz greats like Herbie Hancock and Django Reinhardt.

My favorite part of Coin-Op is when the Hoeys test the limits of comics as a storytelling medium. One strip breaks a parade accident down into a string of interconnected narratives, each given its own progression of individual panels that form part of a greater whole. A wordless strip surveys a crime wave committed by a pigeon. The most surreal strips play out in banal cubicles — beige offices so bland that the reality of the comic strip seems to fold in on itself as an act of rebellion against the boredom of ordinary life.

If, like me, you believe the storytelling range of comics has yet to be fully explored, the Coin-Op anthology is for you. These comics are dancing on the razor's edge between strict formalism and chaotic play. That's where the most interesting stuff always happens.

Book News Roundup: New distribution models

- Seattle comics writer G. Willow Wilson is publishing a new comics series titled Invisible Kingdom with Berger Books, a division of Dark Horse Comics. Berger Books, of course, is the imprint run by longtime DC Comics editor Karen Berger. (I read and loved one of their first titles, Incognegro.) Invisible Kingdom is a collaboration with artist Christian Ward. The Hollywood Reporter describes it as...

The story of two women in a distant galaxy — one a fighter pilot, the other a religious acolyte — who uncover a conspiracy connecting the galaxy’s dominant religion and corporation, Invisible Kingdom sees Wilson return to creator-owned original comic book work for the first time since her 2008 series Air — which was edited by Berger.

Portland small press Microcosm is taking over its own distribution, leaving big distributors out of its business model entirely. I suspect that in the next ten years, we'll see more and more small publishers take on their own distribution models. Microcosm also explained why they're not going to deal with Amazon anymore.

Speaking of alternative distribution models, cartooning website The Nib is running a Kickstarter to fund a quarterly print magazine. The world could use more quality print publications, so give if you can. Without a doubt, the best reward in this campaign is a chance for cartoonist Emily Flake to draw and paint a picture of how you do or do not want to die.

Inspecting expectations

Published July 18, 2018, at 12:00pm

Angela Garbes Like A Mother is pitched as a new kind of book about pregnancy and birth — but what makes it stand out from the crowded shelf, and who should buy it? Author Bonnie J Rough looks at the history of mothering books, and why you might want to pick this one up.

Tonight, visit Folio: The Seattle Atheneum in its new home at Pike Place Market

This afternoon starting at 4 pm, Folio: A Seattle Atheneum celebrates its new home at the Pike Place Market with a big party featuring refreshments and very special guests. Folio is a private library — I wrote about the concept when Folio first opened back in 2015 — that also operates as a co-working office for members, as well as an event space.

It seems like not so long ago, Folio founder David Brewster was welcoming people to Folio in its home under the downtown YMCA. Why the move across town?

"Our lease was expiring at the YMCA," Brewster tells me over the phone. Though Folio could've stayed longer at the YMCA, when the Market opportunity came up — "about 2500 square feet," with views unlike anywhere else in Seattle — he says "we jumped at it for fear of losing it."

Unless you've lived in Seattle your whole life, you may never have stepped foot in the new Folio space. For the last couple decades, it's been home to the Market's offices, but the space began as a meeting hall for a fraternal organization called the Knights of Pythias. In the intervening years, it's also been a dance hall, the city's third Bartell Drugs location, and "a semi-corrupt bingo parlor" called The Lifeline Club.

Many of the features you loved about the old Folio have carried over to the new. The old Folio space held about 13,000 titles, and the new has room for 12,000. But there's more room for people: Brewster says the old events space could comfortably seat 60 people while the new one has room for 90.

Brewster is excited about the Market as Folio's new home for two main reasons. First, he loves that the Market provides "supporting amenities — mainly the restaurants and bars and places to go after an event here." And second, "we really liked the Market vibe with its sense of history and Seattle traditions." In fact, Folio isn't even the first library at the Market: nearly a century ago Pike Place Market had its own branch of the Seattle Public Library system until the Depression forced it to close.

In the new Market space, Brewster says, "we characterize Folio as part of your dream day: you can read and take out books, do work, meet a friend for lunch, and buy some tomatoes. It's your excuse to come back to the Market."

Folio: The Seattle Atheneum, Pike Place Market, 93 Pike St #307, http://www.folioseattle.org 4 pm, free.

Book News Roundup: A new writer in residence at Hugo House, City Arts gets a new home.

- The Hugo House announced yesterday that their newest prose writer-in-residence is Kristen Millares Young:

Co-organizer of the inaugural Seattle’s Writers Resist at Town Hall and co-founder and board chair of InvestigateWest, an award-winning nonprofit news studio known for creative storytelling, Young brings multidisciplinary skills and knowledge to Hugo House along with her experience as a creative writing instructor.

Speaking of Young, she will publish her very first novel in 2020 through Red Hen Press. City Arts published an excerpt of the upcoming book back in 2013.

Speaking of City Arts, J Seattle at Capitol Hill Seattle reports that the magazine will be breaking out of its former Greenwood offices and moving to the Cloud Room coworking space on Capitol Hill. J Seattle points out that they're joining a two-block radius packed full of media outlets

Going the distance

Published July 17, 2018, at 11:55am

When you travel, you don't do it in a straight line. A new book takes a fragmented, mosaic approach to describing a trip to Rome, and it feels more like traveling than just about any travel narrative in recent memory.

Nephilim

When you ask your mother how you came to be

she will look at you presently but be somewhere else.

Her eyes will light with the warm glows of conception

and you will see in her remembrance that you came

forth from light — pure blinding light. As you continue

reading the story that her face always tells, you will

trail her eyes as they land on the figure of her mortal

husband. And then, just like that, the light will be gone

but your mother will be back with you presently. She

will tell you again with her mouth the answer that her

eyes never seem to corroborate…

“Your father.”

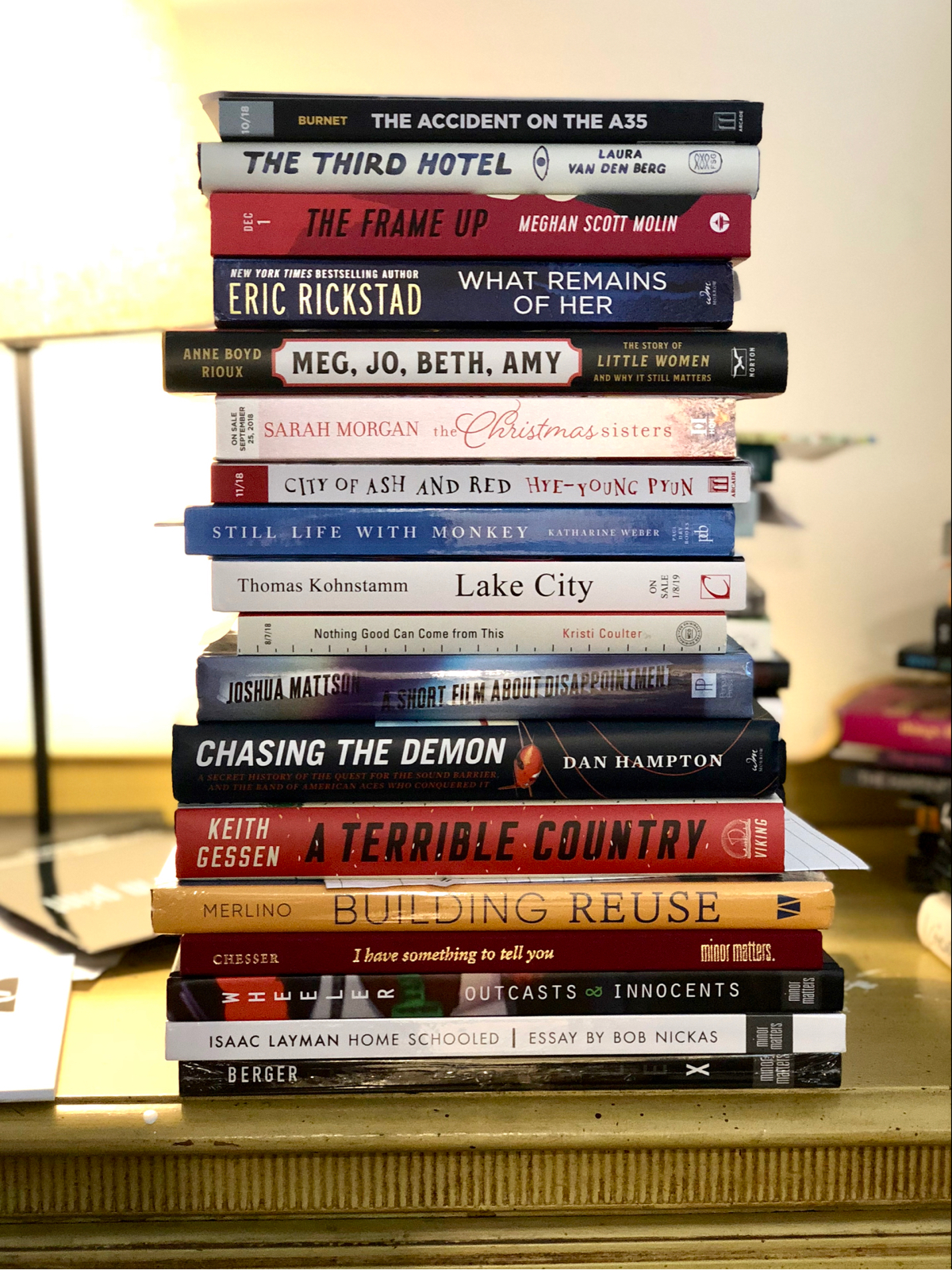

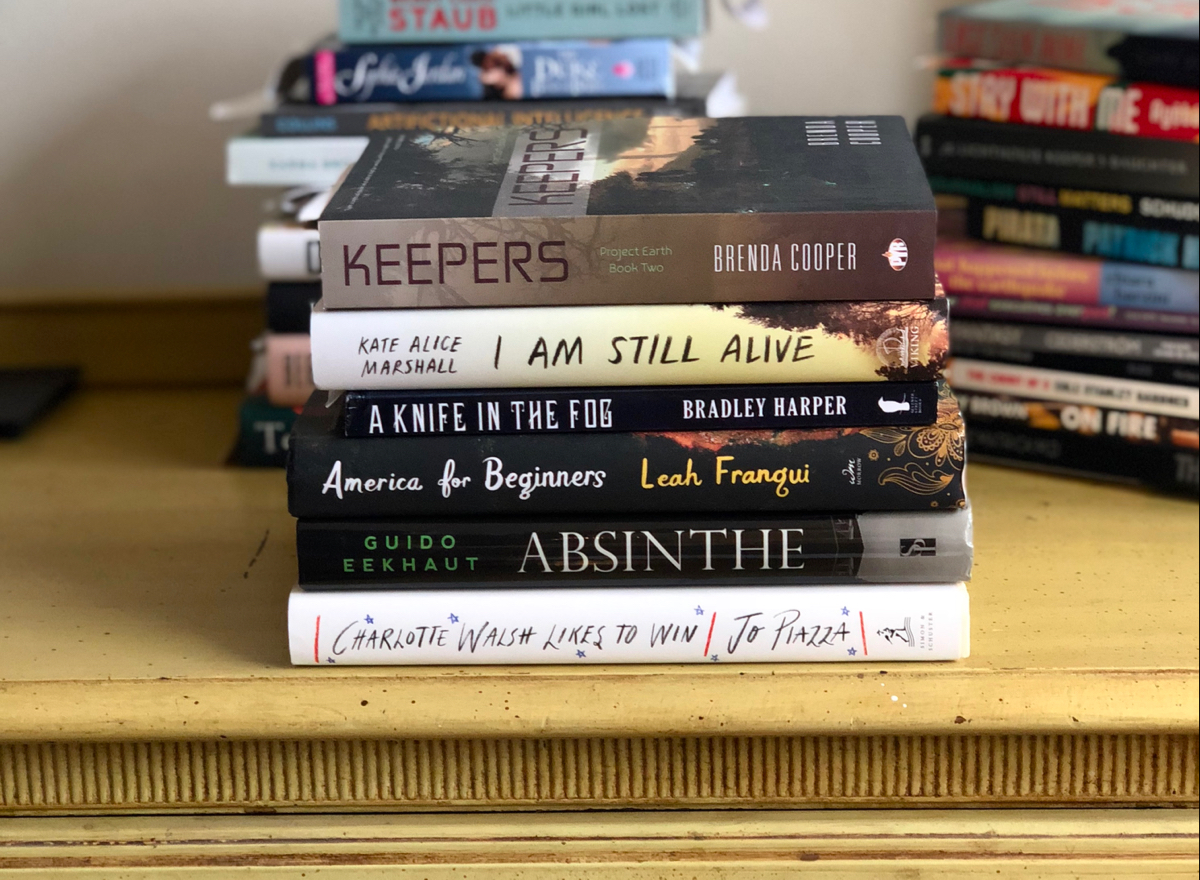

Mail Call for July 16, 2018

The Seattle Review of Books is currently accepting pitches for reviews. We’d love to hear from you — maybe on one of the books shown here, or another book you’re passionate about. Wondering what and how? Here’s what we’re looking for and how to pitch us.

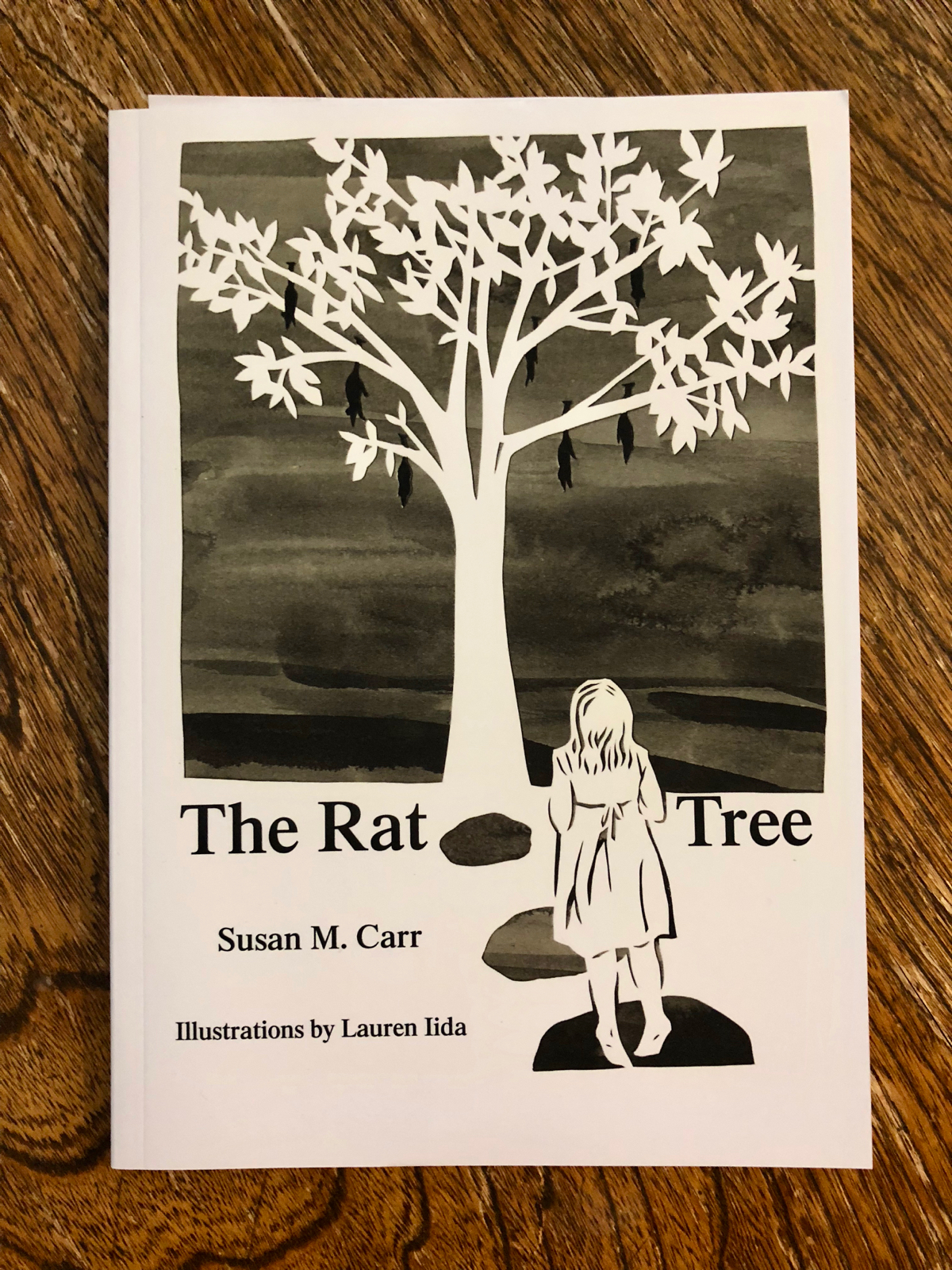

2019 Washington State Book Awards submissions are open!

The awards honor books in a sweeping eight categories, from fiction to memoir to children's lit. Judges are carefully selected: librarians, booksellers, writers; people who not only know their stuff but care deeply about choosing books that represent this literary community's best. The submission period runs now through December 1, but it's not too early to submit; books are reviewed on a rolling basis, and getting in ahead of the rush can't be a bad idea. Check out our sponsorship page for guidelines and details.

And if you're not a writer — put a note on your calendar now to come out for the fall awards ceremony for the 2018 awards, October 13 at the Central Library. Both submitting a book and attending the ceremony are free; the Washington Center for the Book (a partnership of the Seattle Public Library and the Washington State Library), which administers the awards, is committed to making the process and the celebration open to all.

We're so grateful to sponsors like the Washington Center for the Book for supporting this site and helping us publish great writing about books every day. Thanks to them, and our other amazing sponsors, 2018 sponsorships are almost sold out. We'd love to see your book, event, or service for writers promoted here — so reserve a slot fast, before they're gone!

Your Week in Readings: The best literary events from July 16th - July 22nd

Monday, July 16: Beyond Measure Reading

Rachel Z. Arndt has written a collection of essays about the way we quantify our lives: our weights, the times we wake up and go to sleep, the way we try to make ourselves a set of facts and figures for prospective dating partners. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.

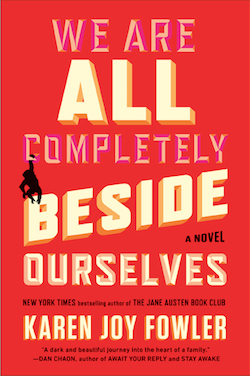

Tuesday, July 17: Karen Joy Fowler

You might best know Karen Joy Fowler for her breakout novel The Jane Austen Book Club, and that novel is a delightful modernization of Austen's work. Her latest novel, We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, is about a family that raises a chimpanzee as though it was a human child. But sci-fi writing organization Clarion West is bringing Fowler to town because she's also a writer of science fiction and fantasy. Seattle Public Library, 1000 4th Ave., 386-4636, http://spl.org, 7 pm, free.Wednesday, July 18: Folio Grand Reopening

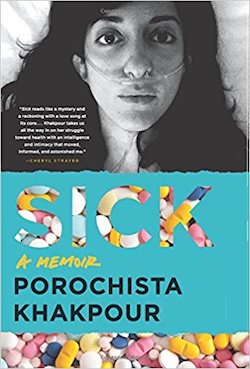

Folio, the private library/events space/coworking space, has moved from its birthplace under the downtown YMCA to a new spot in the Pike Place Market. Today, you are invited to come and meet the Folio board and check out the new digs, which look quite nice. We'll have more about the new space presently on this here website. Folio: The Seattle Atheneum, Pike Place Market, 93 Pike St #307, http://www.folioseattle.org 4 pm, free.Thursday, July 19: Sick Reading

See our Event of the Week column for more details. Elliott Bay Book Company, 1521 10th Ave, 624-6600, http://elliottbaybook.com, 7 pm, free.Friday, July 20: The Corpse at the Crystal Palace Reading

Carola Dunn writes the kind of mysteries that get described as "beloved." Her Daisy Dalrymple series bounces a plucky heroine around in the 1920s, solving mysteries and meeting interesting people. In other words, this is a perfect summertime literary event for you. Third Place Books Lake Forest Park, 17171 Bothell Way NE, 366-3333, http://thirdplacebooks.com, 7 pm, free.Saturday, July 21: Chain Letter

The Capitol Hill reading series returns with a sweaty summer edition featuring Alex Bleecker, Eveline Müller, Nica Selvaggio, and the excellent Graham Isaac. *Vermillion Art Gallery and Bar, 1508 11th Ave., 709-9797, http://vermillionseattle.com, 7 pm, free.Three great reasons to not buy cheap crap today

As all the tech sites are giddily running free publicity for the world's largest online retailer today, I'd like you to consider these two pieces about why you can't trust Amazon as a seller:

The latest episode of the podcast Reply All offers a fascinating look at why "Amazon has suddenly gotten a lot sketchier."

The New York Times examines the "Curious Case of the $2,630.52 Used Paperback."

Imagine your favorite grocery store allowed an unregulated retailer to start selling sketchily sourced knock-offs in their aisles. How would you feel about that?

And more importantly, Amazon warehouse workers around Europe are striking right now. You don't want to cross picket lines, do you? I didn't think so.

Literary Event of the Week: Sick: A Memoir reading at Elliott Bay Book Company

"I have never been comfortable in my own body," Harlem novelist Porochista Khakpour writes in the beginning of Sick, her memoir about life with Lyme disease. "Rather, I've felt my whole life that I was born in the wrong body."

This distance between mind and body, understandably, has always made Khakpour uneasy. And so in some ways, the diagnosis of Lyme disease becomes a convenient metaphor for that distance, for the discomfort she feels inside her own body. This chronic pain and lethargy and weakness at least provides a reason why she might not feel at home in her skin. A few paragraphs later, she concludes:

Because my illness at this stage has no cure, I can forever own this discomfort of the body. I can always say this was all a mistake...I have started to consider that I will never be at home, perhaps not even in death.

Sick is a book that is always bargaining with mortality. Khakpour's story of chronic pain is the story of her existence. "I have been sick my whole life," she says, and the memoir is in many ways about knowing that she'll never know what it means to have good health, that health is the Godot that will never arrive.

When her Lyme disease gets very bad, Khakpour writes cryptic emails to friends asking them to check in on her from time to time. She starts to chafe at friends telling her to "take care of [her]self." She buys a cane. She faints. She tries different drugs. She knows that she'll never recover, which forces her to readjust her understanding of what it means to treat her disease.

Few writers could pull off this kind of a memoir without making it a laundry list of despair. But Khakpour isn't a typical writer: Sick is hypnotic in its examination of bodies in the world, and all the many ways those bodies can (and do) go wrong.

The Sunday Post for July 15, 2018

Each week, the Sunday Post highlights a few articles we enjoyed this week, good for consumption over a cup of coffee (or tea, if that's your pleasure). Settle in for a while; we saved you a seat. You can also look through the archives.

Peterson's Complaint

“Believe me, you are not too dumb to understand this,” says Laurie Penny, right before slicing Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life and Peterson himself into a paper blizzard of puffery, self-pity, and pretension. It’s a tour de force takedown, every breathlessly brilliant insult backed with rigorous logic, a glorious read for the language alone — and also a determined tug on a needle that’s been moving, a bit, and that a lot of angry people would like to re-set to the status quo.

Angry white male entitlement is the elevator music of our age. Speaking personally, as a feminist-identified person on the internet, my Twitter mentions are full of practically nothing else. I've spent far too much of my one life trying to listen and understand and offer suggestions in good faith, before concluding that it's not actually my job to manage the hurt feelings of men who are prepared to mortgage the entire future of the species to buy back their misplaced pride. It never was. That's not what feminism is about.

Barack Obama's Summer Reading

Barack Obama recommends a short list of books by African authors as he gears up for a trip to sub-Saharan Africa to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s birth. The internet has been very gracious in not snarking about our current president’s reading habits while discussing this list, so I’ll try to do the same. (But seriously. A reading list personally curated by the last leader we had who read at all? Yes, please.)

I've often drawn inspiration from Africa's extraordinary literary tradition. As I prepare for this trip, I wanted to share a list of books that I'd recommend for summer reading, including some from a number of Africa's best writers and thinkers — each of whom illuminate our world in powerful and unique ways.

Hannibal Lecter, My Therapist

Here are two essays that use small, harmless things as a device to explore the deeply personal. First Emily Alford, who transforms a childhood viewing of The Silence of the Lambs into a grown-up meditation on poverty, neglect, and loss.

There are all sorts of reasons to go hungry: because the only food in the refrigerator is a pot of something crusted black at the edges and baked grey and brown in the center, meant to last all week, globbed on top of hardened white rice and reheated to hot, runny goo in a microwave where roaches dart across the gummy insides, legs sticking to squirts of months' worth of runny dinners. To see how long it takes for someone to notice the untouched plastic baggies full of slimy lunch meat that accumulate in a lunch box, warm to the touch by the time they return home uneaten. To become so thin the wind might catch flaps in a too-large tee shirt and send a body someplace else, like a balloon loosed from a bunch. When I was a baby, the doctor measured the length of my spine and promised my mother I'd be tall, she likes to tell me. Instead, I stopped growing right smack at average, never claiming the length of bone that serves as a reward for being one generation away from poor white trash.

"Was your daddy a coal miner? Did he stink of the lamp?" Dr. Lecter asks Clarice Starling.

Sweetness Mattered

Then Aaron Hamburger, for whom a pack of Smarties helps clear the way to reclaiming himself after a brutal rape. Both of these are difficult, excellent, and best read in private, when you can give them plenty of space and time.

My parents were midwestern-friendly, polite, though they became increasingly silent, even stoic, as I recounted my story. I imagined that no one in the room had ever encountered a shameful and bizarre story like mine, or someone foolish or weak enough to allow such a thing to happen to him. This was the kind of crime that happened to women. But then, after what had happened, maybe I wasn't really a man.

Don't imagine you're smarter

Neal Ascherson on the experience of reading a more traditional kind of permanent record — the files kept by the secret police to track suspected spies. Thought-provoking in this era where digital surveillance, both commercial and political, is an unavoidable fact of life.

The crowning mercy of human relations is that we don’t know what other people are really thinking about us. They — those others — decide what redacted selection we are offered. But to read one’s police file is — suddenly — to have the curtain pulled open. The self you think you know becomes a mask, concealing a devious somebody else whose relationships are mere espionage fakes.

Whatcha Reading, Anita Sarkeesian?

Every week we ask an interesting figure what they're digging into. Have ideas who we should reach out to? Let it fly: info@seattlereviewofbooks.com. Want to read more? Check out the archives.

Anita Sarkeesian is the creator and executive director of Feminist Frequency. If you haven't watched any of their amazing critical video series (beginning with Tropes vs Women in video games, which landed Sarkeesian as one of the primary targets of the organized harassment known as Gamergate), they're excellently produced, entertaining, and educational looks at video games, movies, and overlooked women in history, always through a feminist lens. Sarkeesian also hosts the Feminist Frequency Radio podcast, and if that wasn't enough, she and podcast co-host Ebony Adams have a new book coming out! History vs Women: History vs Women: The Defiant Lives That They Don't Want You To Know has a street date of October 2nd, but you can get pre-orders in now. Perhaps through a local indie bookshop?

What are you reading now?

I’m currently reading the final entry in NK Jemisin’s The Broken Earth Trilogy. I’d first heard of Jemisin because so many of my friends were raving about her writing. To be completely honest, I started reading The Fifth Season, the first book in the series, about three times before I actually got through it. The early sections just weren’t grabbing me, but of course I wanted to get into it because my friends loved it so much. Then I met Nora and she was so wonderful and smart and thoughtful that I was like, OKAY, GODDAMN IT, I HAVE TO READ THIS THING! Thank goodness I did, because once I got about a third of the way through the first book, I was absolutely riveted. The character development and world building in this series are spectacular. It’s a completely foreign world that nonetheless feels all too familiar because Jemisin, a masterful storyteller, weaves together so many contemporary societal problems and roots them organically in her meticulous fantasy universe. It’s just thrilling to come across writing that’s simultaneously so imaginative and so replete with meaning. The Broken Earth Trilogy reminds me that fantasy isn’t just the stuff of white men warring over a throne; it can be rich, fascinating, complex, and diverse, too.

What did you read last?

Franchesca Ramsey’s Well That Escalated Quickly: Memoirs and Mistakes of an Accidental Activist. Ramsey walks readers through her life and career path. We might see folks “make it big” on YouTube and it’s as if they just burst onto the scene out of nowhere; we often don’t realize the years and years of hard work it took for them to be noticed. In Ramsey’s memoir, she talks about how the video that put her on the map, “Shit White Girls Say To Black Girls,” came to be, and how it helped her get to where she is now, with a show on MTV, and a gig as a writer and correspondent on the (sadly canceled) Nightly Show, among other exciting achievements. She doesn’t shy away from discussing all the bumps along the way, too, and I appreciate Franchesca’s candor about falling into activism, learning how to talk about issues of privilege and oppression, and the ways in which she’s messed up from time to time.

What are you reading next?

My two fave genres are scifi and memoirs so I often just hop between the two. Next I want to read Sick: A Memoir by Porochista Khakpour. Recently, I read one of her novels, The Last Illusion, which I loved. It’s a fascinating tale of a boy who was raised as a bird, a narrative which allowed Khakpour to really explore socially learned masculinity in American culture and its consequences. Sick is her latest book about living with late-stage Lyme disease and the struggles of chronic pain and illness.

The Help Desk: Breaking the code

Cienna Madrid is on summer break. The following Help Desk was originally published on November 20th, 2015.

Every Friday, Cienna Madrid offers solutions to life’s most vexing literary problems. Do you need a book recommendation to send your worst cousin on her birthday? Is it okay to read erotica on public transit? Cienna can help. Send your questions to advice@seattlereviewofbooks.com.

Dear Cienna,

My son hates to read. The rest of the family? That's all we do. We don't have a TV, even. The other five of us could pass every moment of every day with our noses in a book, but our son wouldn't read chocolate if it were a book. We bought him a computer, and he's getting pretty good at programming and really likes it, but I think he needs to let his eyes rest from all of the vibrating pixels every now-and-again. He thinks we're all (the wrong kind of) nerds, and wants us to learn more about the internet. What kind of compromise do you think we can find?

Georgia in Georgetown Heights

Dear Georgia,

You can't force your loved ones to enjoy your hobbies – if that were possible, all of my friends would be wild about American Girl cosplay and farm-to-table spider farming. That said, if your son is programming, he is reading – you just don't get his language.

So buy him a few books that suit his interests and make a parental decree: Read for an hour, then your child can use the computer (and yes, you should definitely be letting him show off his internet skills). The method works: It's how I eventually weaned my cat off porn.

It's difficult to recommend specific books without knowing your son's age and abilities but Python for Kids: A Playful Introduction to Programming and 3D Game Programming for Kids: Create Interactive Worlds with JavaScript both come highly rated for kids 10+. If he's a little bit older, I'd throw in William Gibson's cyberpunk classic, Neuromancer. In fact, that might be a fun book to read and discuss as a family book club project, you nerds.

Kisses,

Cienna

Portrait Gallery: Shin Yu Pai

Each week, Christine Marie Larsen creates a new portrait of an author or event for us. Have any favorites you’d love to see immortalized? Let us know

Thursday, July 12: Forms of the Book

This one looks like a doozy. Three of Seattle’s smartest, most inventive writers — Amaranth Borsuk, Doug Nufer, and Shin Yu Pai — get together to discuss the past, present, and future of the book.

Ada’s Technical Books, 425 15th Ave, 322-1058, http://seattletechnicalbooks.com, 7 pm, free.

Future Alternative Past: Yesterday's bleak tomorrow

Every month, Nisi Shawl presents us with news and updates from her perch overlooking the world of science-fiction, fantasy, and horror. You can also look through the archives of the column.

And I feel fine

What’s more within SFFH’s wheelhouse than the end of the world as we know it? As a child I watched cowboy movies in theaters with clearly marked radiation shelter entrances, and practiced hiding from nuclear attacks under my flimsy little school desk. But when a babysitter stopped me from eating snow because “the Russians” had poisoned it with bomb tests, I knew hiding was no use. Snow falls everywhere.

In SFFH literature that duck-and-cover strategy was just as futile. Nevil Shute’s contemporary classic On the Beach depicted a bunch of Australians awaiting inevitable death in a nuclear war’s wake. Pat Frank’s Alas Babylon was another bestselling novel of the nuclear holocaust. Theodore Sturgeon’s “Thunder and Roses”, and Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains” and “The Garbage Collector” are powerful short stories on the same topic. It’s like writers are subject to the same traumatizing expectations as the rest of us (sarcasm emoji).

But as the nature of real-world catastrophes has mutated, their SFFH depictions have changed. The likelihood of atomic warfare lessened. In its place loomed twin specters: ecological devastation and plague. Suzy McKee Charnas’s 1974 novel Walk to the End of the World is a “nice” mash-up: an ecological disaster drives government bureaucrats into the (real-life) underground enclaves designed to protect them from nuclear attack; from there they bring forth a horrifically misogynistic society in which cannibalism is a woman’s best option.

James Tiptree, Jr.’s “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” came out in 1969, a plague-pocalypse still spawning tributes such as Joanne Rixon’s unpublished “The Last Flight of Ashley Drescher.”

Octavia E. Butler’s Lilith’s Brood series begins in the aftermath of a global nuclear war; that path to annihilation still seemed open when she began the trilogy with Dawn in 1987. But already in 1983 she was exploring the plague-ridden road to oblivion in her Hugo Award winning “Speech Sounds,” a short story imagining the quick dissolution of civilization under an onslaught of contagious aphasia and illiteracy.

Zombies power most plague-focused SFFH apocalypses, with horror their regular turf — although SF has hosted some thought-provoking zombie tales too. A few of my favorites across spec fic subgenres are The Loving Dead by Amelia Beamer, Lord Byron’s Novel by John Crowley, The Girl with All the Gifts by M.R. Carey, and Zone One by Colson Whitehead.

SFFH explores various depictions of outraged nature’s effects on us. In John Varley’s Slow Apocalypse, runaway bioweapons destroy the entire world’s oil fields in a matter of days, leading to massive cultural regression. In Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 and Tobias Buckell’s Arctic Rising, though, no additional action is needed to bring the planet’s delicately balanced natural forces tumbling down on our heads — they’re already falling. To be sure, in these two examples, at least, life goes on — but a radically different life.

The idea of eco-catastrophe is something we have always had with us, journeying beside us through those nightmare atomic wastelands. Pairing it up with that stalwart of the genre, alien invasion, Jeff VanderMeer has written Area X: The Southern Reach Trilogy. He describes not so much an apocalypse as a breach in consensus reality, with gnomic messages left for Area X’s explorers via luminescent slug trails and similar shifting, rotting, signifiers.

What’s next? Perhaps a sudden spate of political disaster fiction. Slate published ten pieces of it for their 2017 Trump Story Project. Christopher Brown’s Tropic of Kansas supposedly takes place in an alternate universe, but the oppression and cognitive dissonance of its setting are nauseatingly familiar. Fortunately it ends where I also want to wind up: in hopefulness.

Recent books recently read

Summerland (Tor), the new novel by former mathematical physicist Hannu Rajaniemi, takes place in a bona fide afterlife, which should be a locus of hope. But like the mortal world it’s divided along national boundaries, and ghostly spies compete just as fiercely for dominance there as here. Lovecraftian lurkers await in Summerland’s unexplored depths; British agent Rachel White and the Russian mole she hunts struggle above this dark abyss. The mole longs for the certitude denied by The Liar’s Paradox but promised by submergence in the group mind that comprises the Soviet’s Heaven. White longs to defend her country, repair her career in government espionage, and rescue her faltering marriage to a veteran of ectoplasmic combat. Following the lines of their conflicting and overlapping desires, I as a reader felt satisfied again and again by the author’s ability to convey humankind’s universal and eternal weaknesses and strengths.

Pulled together from novellas published primarily on her Patreon fundraising site, Kameron Hurley’s Apocalypse Nyx (Tachyon)is a welcome return to the adventures of the author’s iconic hard-fisted anti-heroine. An ex-government assassin both rogue and scrupulous, by the end of the book Nyx has survived to the ripe old age of thirty something despite her penchant for binge drinking and her disregard for commonly accepted rules of engagement. These five glimpses into her passage from an explosives expert fresh off a centuries-old battlefront to a bounty hunter in war-ravaged cities and villages show her being both tender and tough, both reckless and cynical. My favorite story’s the final one, in which Nyx notes how ridiculous it is for a killer like herself to have a panging conscience — but declines a ride home out of the desert from colleagues who set fire to a house full of children anyway.

Second of her non-Temeraire books, Naomi Novik’s Spinning Silver (Del Rey) revisits the vaguely European fantasy milieu of her award-winning novel Uprooted. Jewish folklore underpins them both, but this new story’s much grimmer. Famine; unnaturally prolonged winters; persecution by Christian neighbors; physically abusive fathers and distantly scheming ones; all these harshnesses have a chilling effect on the intertwined tales of Miryem and Wanda of Pavys, and Irina, daughter of a nobleman and bride of a demon-possessed tsar. The nameless king who commands Miryem to change his silver to gold is conquered not by cheating but by the magic that comes only “when you [make] some larger version of yourself with words and promises, and then [step] inside and somehow [grow] to fill it.” Multiple first-person perspectives simultaneously narrow and widen the narrative. All this renders Spinning Silver uncomfortable, unorthodox, and unforgettable.

A non-con and a no-go

On August 18 I’ll take part in an afternoon of subversive thinking called Economic Utopias and Dystopias here in Seattle. There’s no link for me to share with you yet — no website — but we’ll start with a 2pm panel discussion and move on from there to a world building exercise. Stay tuned for the location and names of co-conspirators.

Meanwhile, I full-throatedly recommend you not attend Dragoncon, the self-declared “largest multi-media, popular culture convention focusing on science fiction & fantasy, gaming, comics, literature, art, music, and film in the universe.” Basically, they’ve decided it’s best to tolerate intolerance; they’ve invited a notorious racist, homophobic, misogynist harasser and fired the woman who called him out.